Contents

- SMRTnet bypasses the difficulty of obtaining RNA 3D structures. Using only the more accessible 2D diagrams, it efficiently predicts small molecule binders, opening new doors for RNA-targeted drug discovery.

- Shifting from viewing individual amino acid “letters” to structural fragment “words” solves the long-standing problem of AI models “forgetting the beginning” of large proteins.

- By optimizing molecules on curved manifolds that better reflect physical reality, the R-DSM method achieves chemical accuracy in structure and energy predictions.

- Single-cell analysis is moving from mapping cell atlases to predicting perturbation effects. This requires building causal models, not just performing correlation analysis.

- NTv3 is the first model to integrate accurate genomic sequence prediction and controllable generation into a single, unified, cross-species foundational model, enabling both “reading” and “writing” of the genomic language.

1. How Do You Screen for RNA-Targeting Drugs Without a 3D Structure?

For decades, targeting RNA with small molecules has been a goal for many in drug discovery. After all, a huge number of RNAs in the genome play key roles in causing disease. But progress has been slow, held back by one major obstacle: we don’t know the 3D structures of most RNAs.

Proteins usually fold into relatively stable structures, forming clear “pockets” where drug molecules can dock. RNA is different. It’s more like a flexible rope, constantly changing shape, which makes it hard to capture a stable 3D form. Without this 3D blueprint, traditional Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) is impossible.

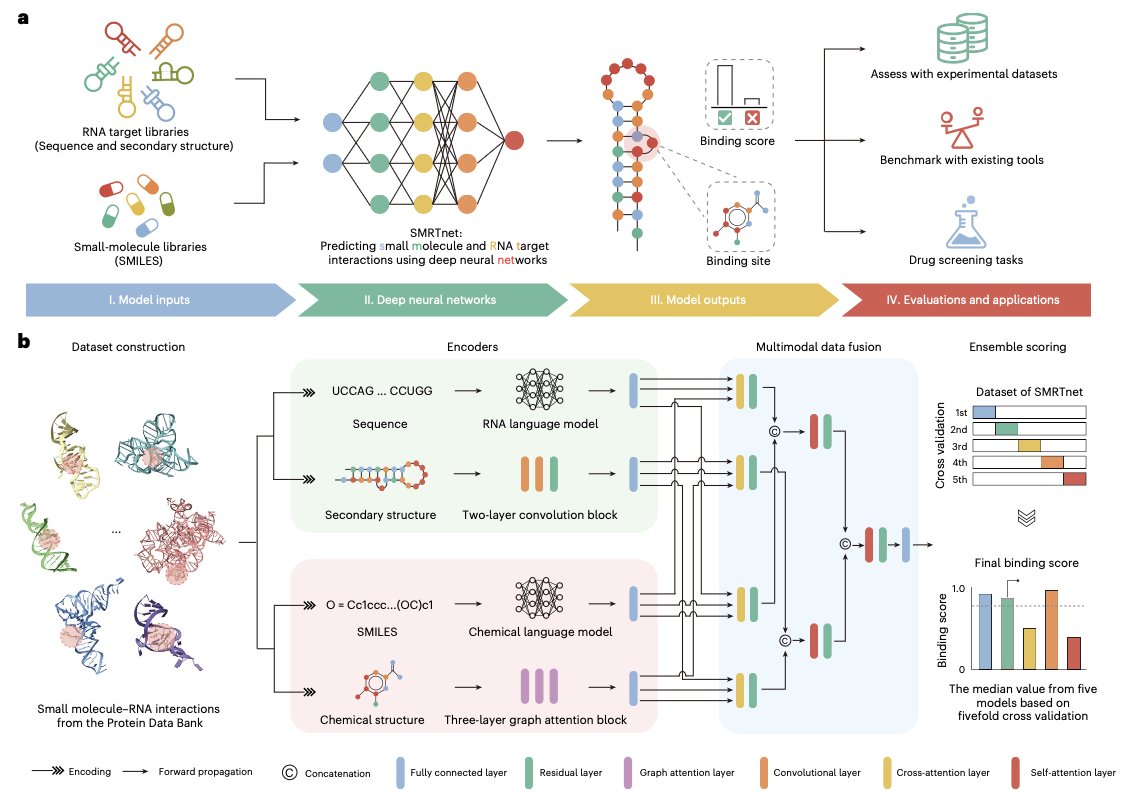

This work from Nature Biotechnology, called SMRTnet, offers a solution: if we can’t get the 3D structure, let’s just not use it.

SMRTnet’s core idea is to use RNA’s secondary structure to predict small molecule binding. The secondary structure describes how the RNA strand folds and pairs with itself to form basic motifs like stem-loops and hairpins. You can think of it as a circuit diagram. It doesn’t show the precise 3D position of each component, but it clearly marks the connections between them. And getting this “circuit diagram” is much easier than obtaining a full 3D model.

Here’s how the model works: it has two parallel “expert” modules. One module specializes in “reading” the RNA’s secondary structure and sequence information. The other is responsible for “parsing” the small molecule’s chemical structure (input as a SMILES string). After each module extracts what it considers the most important features, a fusion module integrates this information to output a predicted binding score. The process is a bit like two experts from different fields—a biologist and a chemist—sitting down together to decide if a molecule and an RNA are a good match.

To test it, the researchers used SMRTnet to run a virtual screen against 10 disease-related RNA targets. The results were encouraging. In experimental validation, the predicted compounds had a hit rate of 21.1%. In the world of virtual screening, that’s a very good result.

They also discovered a lead compound that could target the transcript of the MYC gene. Experiments confirmed that this compound did, in fact, downregulate MYC expression and inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells. This completes a full cycle from computational prediction to biological validation, proving SMRTnet’s practical value.

Another key feature is the model’s explainability analysis. SMRTnet doesn’t just tell you “this molecule binds”; by analyzing its attention weights, it can also highlight the binding regions it thinks are most important. This is invaluable for medicinal chemists. It provides a “target map” for the drug’s action, guiding future modifications to improve potency and selectivity.

To prove the importance of the secondary structure, the authors also ran a control experiment. They removed the RNA secondary structure information from the input, and the model’s predictive performance dropped significantly. This result clearly shows that the RNA’s secondary structure “circuit diagram” is the key to SMRTnet’s success.

The arrival of SMRTnet means we can now perform large-scale virtual screening on thousands of RNA targets that were previously ignored due to a lack of structural information. It has substantially lowered the barrier to RNA-targeted drug discovery.

📜Title: Predicting small molecule–RNA interactions without RNA tertiary structures 🌐Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-025-02942-z

2. Can We Cure AI’s ‘Amnesia’ with Large Proteins?

Anyone in computational drug discovery has probably faced this frustrating problem: you try to use a Large Language Model to process a huge protein like Titin, and the model just gives up. The model has a limited input length. If you feed it a sequence with tens of thousands of amino acids, it will either throw an error or forget the beginning by the time it reaches the end. We call this “semantic truncation,” and it’s fatal for understanding a protein’s overall function.

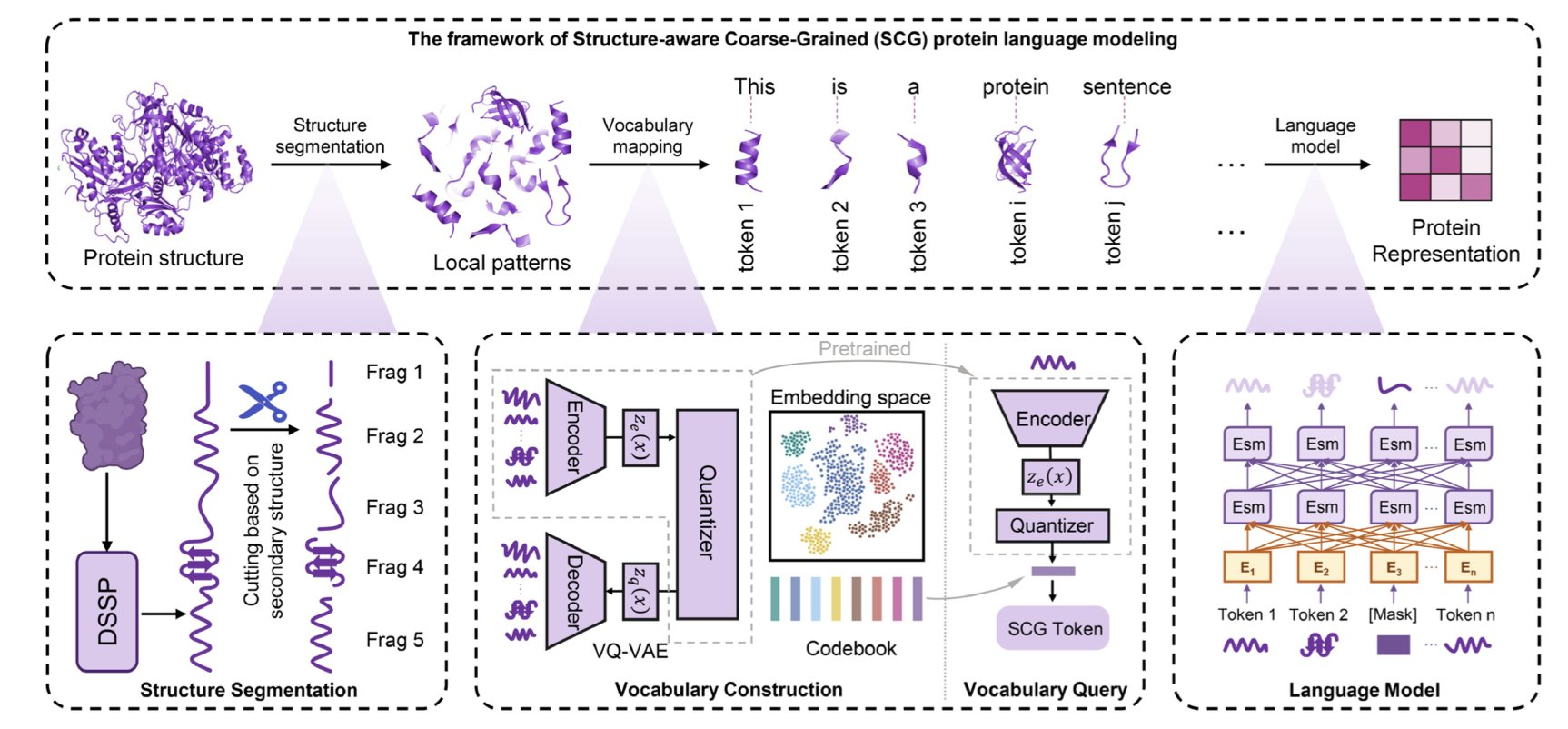

This paper offers a clever way to solve the problem. The core idea is this: let’s stop making the model read amino acid “letters” one by one and instead teach it to read meaningful “words” made of those letters.

What are these “words”? They are the secondary structure elements of a protein, like alpha-helices and beta-sheets. These are the basic functional and structural units. The researchers developed a framework called SCG (Structure-Aware Coarse-Grained). It works in two steps: 1. Segmentation: First, it chops the protein sequence into small structural fragments based on its secondary structure. A long helix or a large sheet becomes a single unit. A sequence of tens of thousands of “letters” is instantly condensed into a sequence of a few thousand, or even a few hundred, “words.” 2. Encoding: Next, it uses a technique called Vector Quantization to create a “vocabulary” for these structural fragments. A VQ-VAE model scans a massive database of protein structures, automatically learning and summarizing a dictionary of several thousand common “structural chunks.” Any fragment from a real protein can be matched to the most similar “standard word” in this dictionary and represented by a unique ID.

With this process, any protein, no matter how large, can be converted into a short sequence of “structural word” IDs.

How well does it work? The effect is immediate. A comparison chart in the paper clearly shows the power of this method.  In this chart, the x-axis is protein length and the y-axis is information retention. The traditional fine-grained language model shows a sharp drop in retention for long proteins, while the SCG method (SCG-Lang) is almost a flat line, barely affected by length.

In this chart, the x-axis is protein length and the y-axis is information retention. The traditional fine-grained language model shows a sharp drop in retention for long proteins, while the SCG method (SCG-Lang) is almost a flat line, barely affected by length.

To prove that segmentation by secondary structure was the key, the researchers ran a control experiment. When they sliced the protein randomly or used dynamic programming instead, the performance dropped sharply. This shows that basing the segmentation on biological principles is what makes it work.

This method not only solves the truncation problem for large proteins but also performs well on various downstream tasks, like protein function prediction, enzyme classification, and interaction recognition. Its advantage holds whether it’s used in a lightweight or a deep model.

For researchers on the front lines, this means we finally have an efficient tool to handle protein targets that were previously too large to model. It opens a new door to understanding the massive molecules involved in complex diseases and designing drugs for them.

📜Title: Molecular-level protein semantic learning via structure-aware coarse-grained language modeling 🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaf654 💻Code: https://github.com/bug-0x3f/coarse-grained-protein-language

3. Why Is Molecular Structure Prediction Always a Little Off? The Answer Might Be in Geometry.

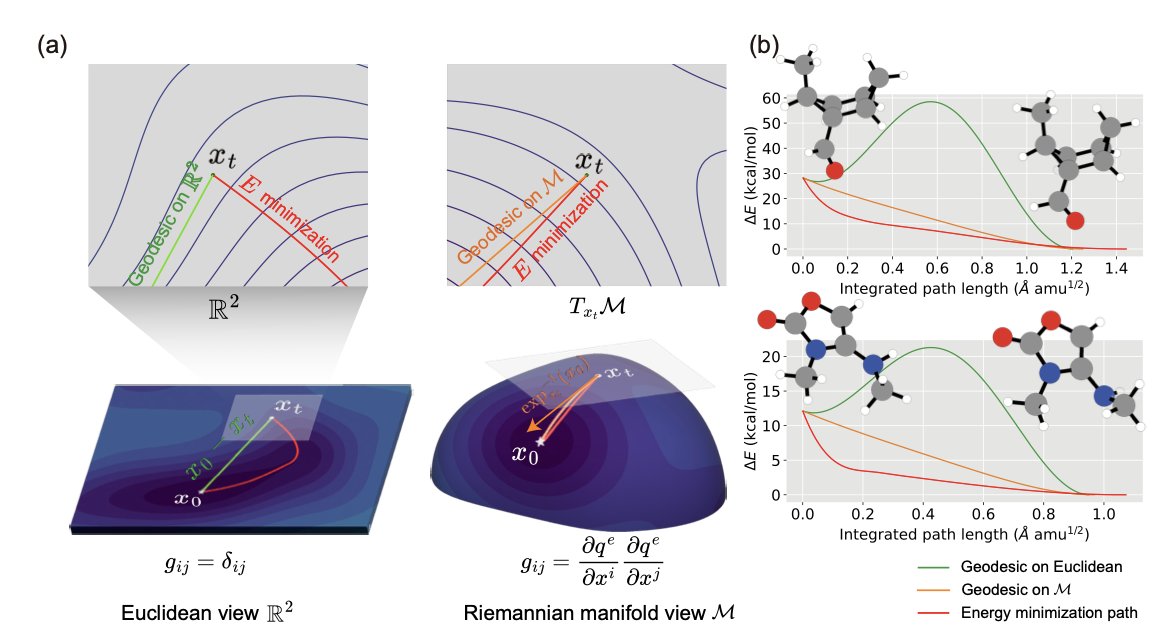

In drug discovery, we deal with the 3D structures of molecules all the time. Finding a molecule’s lowest energy conformation is like searching for the lowest valley in a complex mountain range. Most traditional computational methods perform this search in a flat, Cartesian (x, y, z) space. That’s like using a flat city map to find a valley. The general direction might be right, but the distances and paths are all wrong because mountain trails are curved, not straight.

This work, published in Nature Computational Science, offers a new approach: why not use a “contour map”? A contour map is inherently curved and perfectly reflects the mountain’s terrain. In mathematics, this kind of curved space is called a Riemannian manifold.

The researchers build this manifold using a molecule’s internal physical coordinates—its bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles. This is the language chemists are most familiar with and the way a molecule “feels” its own geometry. On this more natural manifold, they developed a model called Riemannian Denoising Score Matching (R-DSM).

Here is how it works. First, you take a perfect molecular structure and add some random “noise” to it, nudging it away from its lowest energy point. The model’s job is then to learn how to push the perturbed molecule back to its original state along the “shortest path” (a geodesic) on the manifold. Because this path follows the “valley” of the energy landscape, it’s much more efficient and accurate.

The data speaks for itself. The researchers found that the geodesic distance between two points on this manifold correlates much better with the true energy difference than the traditional root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 3D coordinates. When tested on the standard QM9 dataset, structures generated by R-DSM had a median energy error of just 0.177 kcal/mol and an RMSD as low as 0.031 Å. This is a remarkable achievement, reaching the level often called “chemical accuracy.”

What is this good for? One direct application is structure refinement. For example, we could use a fast but inaccurate method like a molecular mechanics force field (MMFF) to generate an initial conformation, then use R-DSM to “polish” it to quantum mechanics (QM) level precision. This could save a huge amount of computational resources. It also excels at generating sets of conformational isomers, which is critical for understanding molecular flexibility and drug-target interactions.

The model’s core is a graph neural network based on the SchNet architecture, and it uses an ordinary differential equation (ODE) solver for sampling.

For now, the method is more of a refinement tool; it needs a decent starting structure. If it can be further optimized to rely less on an initial geometry, or even be used for de novo generation, its applications would be much broader. But it proves that solving a problem in the right geometric space can make all the difference.

📜Title: Riemannian denoising score matching for molecular structure optimization with accurate energy 🌐Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43588-025-00919-1

4. Beyond the Plots: What Else Can We Do with Single-Cell Data?

We have more and more single-cell sequencing data, and our UMAP plots are getting prettier. But we face a sharp question: besides telling us what cells are here, what can this data do? Can we use it to predict the effect of a new drug? Or what happens to a cell’s network after we knock out a gene?

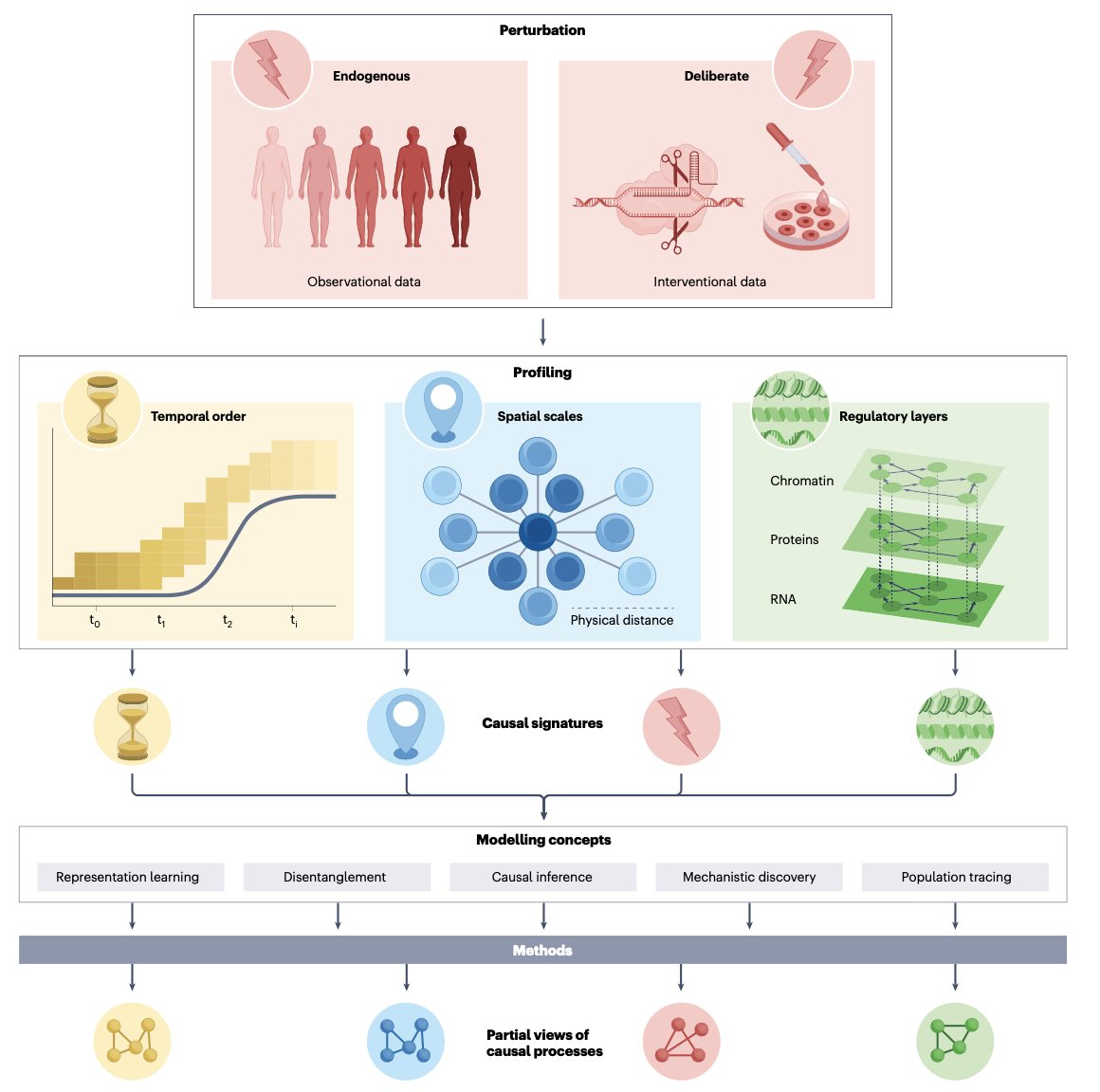

This review, published in Nature Reviews Genetics, gets right to the point. It tells us the entire field is undergoing a critical shift: from the era of descriptive “cell atlas mapping” to a more challenging era of “causal inference.”

Previous single-cell analysis was like making a high-resolution city map. We could use it to pinpoint every building and street. That’s an important foundation. But now, we want to be city planners. We don’t just want to know where the hospital is; we want to predict how building a new subway station there will affect traffic flow and property values across the city. In biology, this “subway station” is a perturbation, like a drug treatment, gene edit, or disease state.

To do this, data alone isn’t enough; we need the right analytical tools. There is a bewildering array of computational methods available today. The authors of this review have done something important: they’ve tried to create a “method selection guide,” which they call an “ontology.” They categorize existing methods based on their modeling approach, underlying assumptions, and the problems they can solve. It’s like an instruction manual for a toolbox, telling you when to use a hammer and when to use a screwdriver, instead of just grabbing one at random. This framework can help us select the most appropriate model for a specific biological question, like predicting the synergistic effect of a drug combination or inferring the downstream targets of a transcription factor.

This touches on a major challenge in the field today: our algorithms are getting more complex and can, in theory, capture fine-grained causal relationships. But in reality, the data we have is often not “clean” enough, or doesn’t have enough dimensions, to support such complex models. It’s like putting a top-of-the-line racing engine into the chassis of a family car—you can’t use its full power.

This makes establishing a standard system for model evaluation and benchmarking essential. We need to know objectively how a new method is better than an old one, not just who tells a better story.

The future direction is clear. We need to integrate more data types, like spatial-omics and proteomics, to connect the dots of how a perturbation signal travels through different molecular layers. This will let us see how a “cause” truly leads to an “effect.” Only then can single-cell analysis transform from a visualization tool into a “crystal ball” that can guide drug discovery.

📜Title: Interpretation, extrapolation and perturbation of single cells 🌐Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41576-025-00920-4

5. NTv3: Reading and Writing the Language of Genomes Across Species

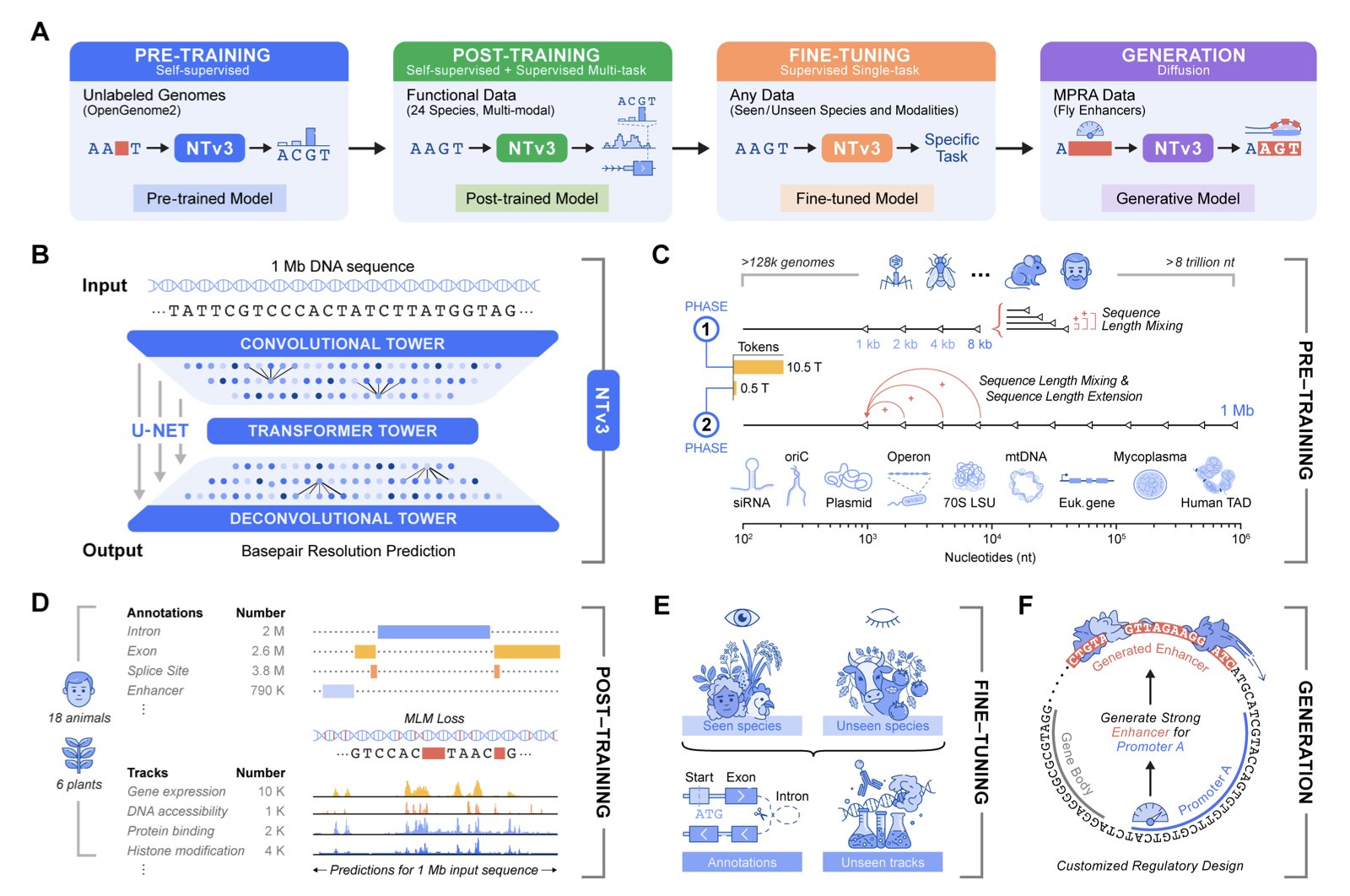

In genomics research, we’ve always faced a core challenge: we have the DNA sequence—the “book of life”—but understanding its grammar has been incredibly difficult. A particularly tough problem has been figuring out how distant DNA segments “talk” to each other to control gene expression, known as long-range regulatory dependencies. Previous models either couldn’t see far enough or weren’t generalizable across species.

Researchers at InstaDeep have introduced a new model called NTv3 to try and solve this.

NTv3 has an interesting architecture, similar to a U-Net. You can think of it as a system that can see both the individual “trees” (single bases) and the “forest” (megabase-scale regions). This allows it to process local sequence features and global information up to 1 Megabase (Mb) away at the same time. To train this massive model, the researchers fed it 9 trillion base pairs from different species. This is like teaching an AI not just modern English but also Old English, Latin, and Greek, allowing it to grasp the common underlying logic of all languages.

The model’s predictive power is strong. It outperformed all existing models on over 16,000 functional annotation tasks. But the authors didn’t just stop at beating existing benchmarks. They developed their own new and more realistic benchmark suite with 106 tasks, called Ntv3Benchmark. NTv3 was still number one on this new test, proving its capabilities are robust and not just tuned to specific problems.

But if NTv3 could only “read” the genome, it would just be a better prediction tool. What really makes it stand out is that it can also “write.”

Through fine-tuning, NTv3 can be turned into a controllable generative model. This means we can give it instructions, like: “Design me an enhancer sequence that efficiently and selectively activates Gene A, but doesn’t touch Gene B.” It’s like being able to not only read Shakespeare but also write a sonnet in his style on a specific topic. In the paper, the authors show how they generated enhancers with specific activity levels and promoter selectivity. And crucially, they didn’t just generate the sequences on a computer—they actually performed experiments to validate them. The results showed that the performance of these engineered enhancers in cells closely matched the model’s predictions.

NTv3 successfully packs accurate representation learning, functional prediction, and controllable sequence generation into a single framework. It is not an isolated tool but a platform—a true foundational model for genomics. For drug discovery, this means we can gain a deeper understanding of disease-related gene regulatory networks and perhaps even design gene therapy components that precisely regulate specific genes.

📜Title: A Foundational Model for Joint Sequence-Function Multi-Species Modeling at Scale for Long-Range Genomic Prediction 🌐Paper: https://instadeep.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/NT_v3.pdf