Table of Contents

- MONDE·T offers an interactive platform with experimental data, allowing researchers to visually analyze how non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) affect protein backbone structures.

- PackDock uses a diffusion model to solve the critical problem of side-chain conformation in flexible docking, making accurate predictions even from apo structures and opening new avenues for drug discovery.

- Using an improved attention mechanism and a “scale-out” approach, SeedFold surpasses AlphaFold3 on several key tasks, showing that brute-force scaling can deliver results.

- A new framework separates molecule “generation” and “screening,” using a sorting algorithm to find good molecules faster and in larger batches from a vast chemical space.

- SeedProteo leverages AlphaFold3’s architecture with a clever self-guidance and sequence decoding method to achieve high-precision, all-atom de novo protein design, performing especially well on protein binders for drug discovery.

1. How Do Non-Canonical Amino Acids Distort Proteins? A New Database Has the Answer

When we do protein research and drug design, we spend most of our time with the 20 standard amino acids. But proteins often contain “non-mainstream” amino acids, either from post-translational modifications (PTMs) in nature or from chemical synthesis in the lab.

The question is: when a non-canonical amino acid (ncAA) appears in a peptide chain, how does it affect the protein’s local conformation? Will it behave like the standard amino acid it most resembles, or will it twist the peptide backbone into a completely new angle? Answering this used to be a painful process. You had to manually search the Protein Data Bank (PDB), gathering scattered data, which was extremely inefficient.

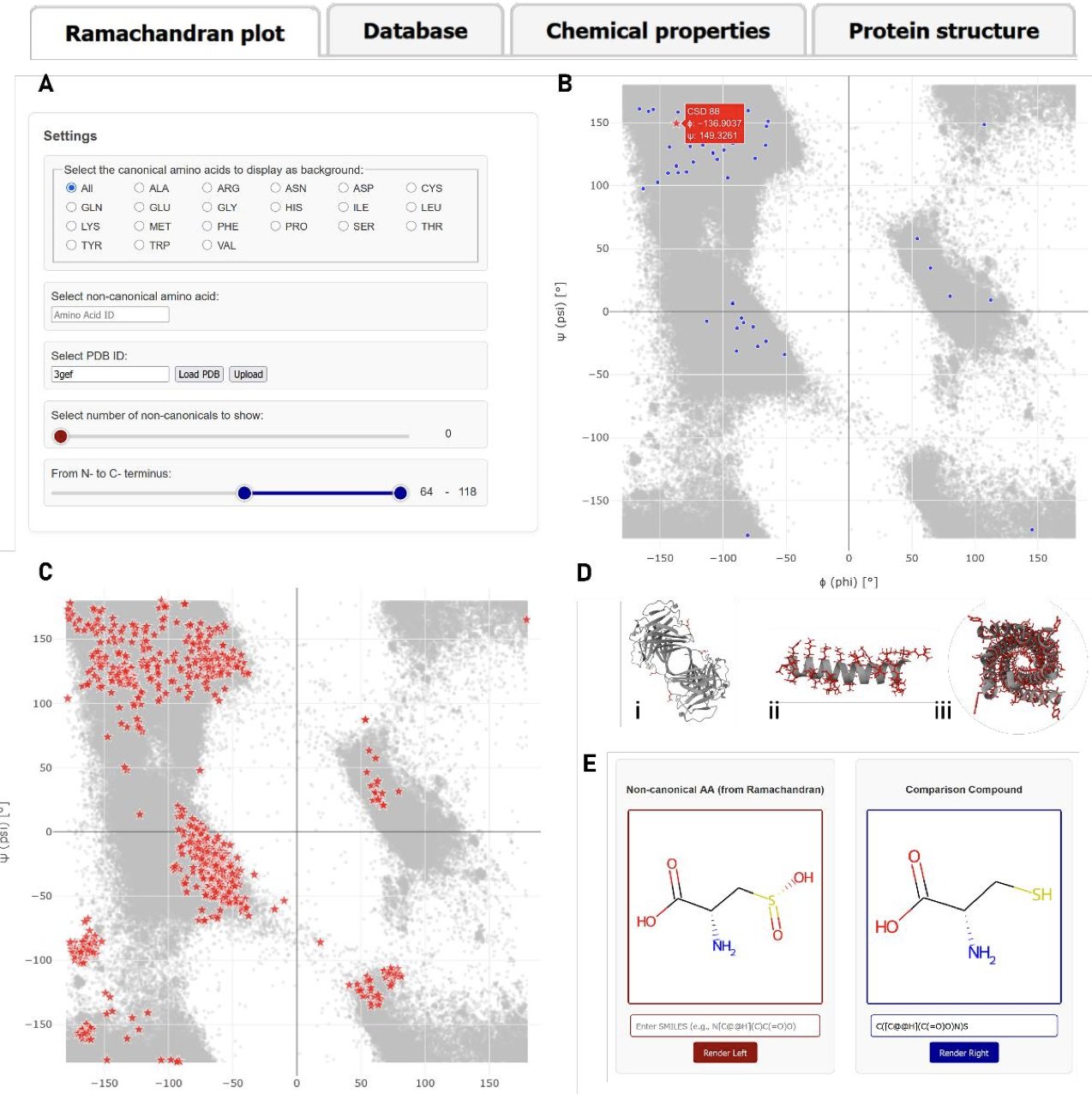

Now, researchers have developed a database and web server called MONDE·T to solve this exact problem. They systematically combed through the entire PDB, organizing 1,875 different non-canonical amino acids from over 10,000 entries. This isn’t just a list; they preserved the complete structural context for each ncAA.

The most useful part of this tool is its interactive analysis feature.

The core of it is the Ramachandran plot visualization. You can input any ncAA you’re interested in (like phosphoserine), and the server instantly generates a plot. This plot shows the backbone dihedral angles (phi-psi angles) of all known phosphoserine instances in the PDB, with the conformational distribution of standard amino acids as a background.

The answer becomes clear at a glance. You can immediately see if this modified amino acid prefers the α-helix region, the β-sheet region, or if it occupies an entirely new space. This is critical for understanding how post-translational modifications regulate protein function or for designing new peptide drugs. For example, if you want to know whether replacing a glycine with its analog will disrupt a key turn structure, this tool gives you a quick answer.

MONDE·T also offers a chemical similarity comparison tool. Based on the Tanimoto similarity coefficient, it tells you which standard amino acid a particular ncAA is most similar to in 2D structure. This gives us a chemical intuition to quickly judge its potential physicochemical properties.

The database has a wide range of applications.

1. Post-translational modifications: Want to know the specific impact of phosphorylation, methylation, or acetylation on the protein backbone? Just look up the corresponding modified amino acid.

2. Synthetic biology: When introducing non-canonical amino acids into proteins using stop codon suppression, you can pre-assess their impact on structural stability.

3. Peptide drug design: When using amino acid analogs to optimize a peptide’s drug-like properties (like stability or affinity), you can use it to guide structural design and avoid introducing unfavorable conformations.

The researchers promise to update the database every six months to keep the data current. For anyone in protein engineering, computational drug design, or peptide chemistry, MONDE·T is a very handy tool. It can reduce analysis work that used to take days or even weeks down to just a few minutes.

📜Title: Monde·t: A Database and Interactive Webserver for Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs) in the PDB

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.21.695100v1.full.pdf

2. Flexible Protein Pockets? AI Solves Docking with a Diffusion Model

In drug discovery, molecular docking is a standard tool. But we all know its fatal flaw: it usually assumes the protein target is a rigid lock and the ligand is the key. In reality, protein pockets are far from static. They adjust their shape to accommodate the right ligand in a process called “induced fit.” The flexibility of amino acid side chains is the key part of this process, and also the most difficult to handle.

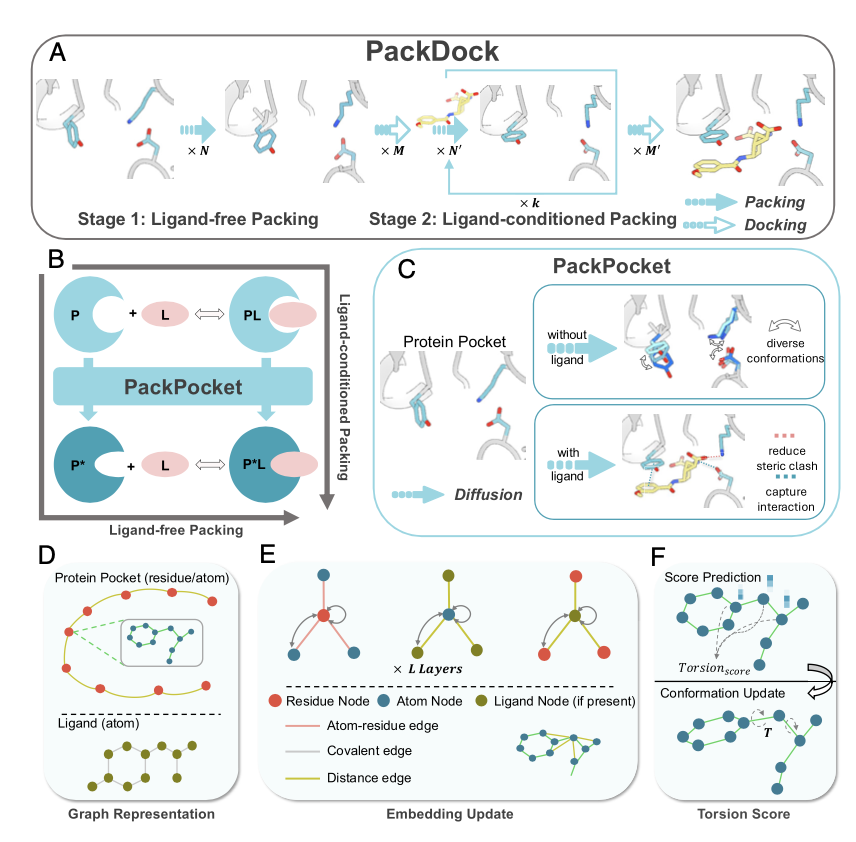

Now, a new study in PNAS proposes a framework called PackDock to tackle this tough problem. Its approach cleverly combines popular deep learning techniques with classical physics models.

The core of PackDock is a module called PackPocket, which uses a diffusion model. If you’re familiar with AI image generation, you know how powerful diffusion models are at creating images. They start with random noise and gradually “denoise” it to produce a realistic picture. PackPocket does something similar, but instead of images, it generates the 3D conformations of amino acid side chains in a protein’s binding pocket. It can sample conformations for both ligand-free (apo) and ligand-bound (holo) states of the pocket.

What problem does this solve? In drug screening, we often only have the apo crystal structure of a target. When a new molecule binds, the pocket shape will almost certainly change. If your docking tool can’t predict this change, the results can be way off. PackDock can directly predict how side chains will move to accommodate a ligand on the apo structure, making the starting point for docking more accurate.

The researchers tested its performance in several standard benchmarks.

1. Side-chain prediction: It accurately predicts which amino acid side chains will rotate and how they will do so upon ligand binding.

2. Redocking: Putting a known ligand back into its original structure. This is a basic test, and PackDock performed well.

3. Cross-docking: A more rigorous test that involves docking a ligand into different crystal structures of the same protein. PackDock also excelled here.

Its real-world case study was the most impressive. The team applied it to the target aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1 (ALDH1B1). Using PackDock, they not only found molecules that could bind to the target but also identified compounds with novel chemical scaffolds and nanomolar activity. Starting from a computational model and directly finding highly active new scaffolds demonstrates PackDock’s practical value. It’s not just a toy that gets good scores on a computer; it’s a tool that can actually guide experiments and discover new drug candidates.

PackDock can also tell us which amino acid conformations change critically during binding. This is essential for understanding the drug’s mechanism of action and guiding subsequent molecular optimization. For researchers on the front lines, this information helps us figure out how to modify a molecule to get better activity and drug-like properties.

📜Title: Flexible protein–ligand docking with diffusion-based side-chain packing

🌐Paper: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2311925121

3. SeedFold Takes on AlphaFold3 with More Compute

Ever since AlphaFold appeared, everyone has been thinking about the same thing: what’s the next breakthrough? We all know these structure prediction models are powerful, but training them is a bottomless pit of computational cost. The main problem is the core triangular attention mechanism, whose computational complexity is cubic with respect to sequence length. This means that as proteins get even slightly longer, the computation explodes.

The researchers behind SeedFold decided to tackle this problem head-on.

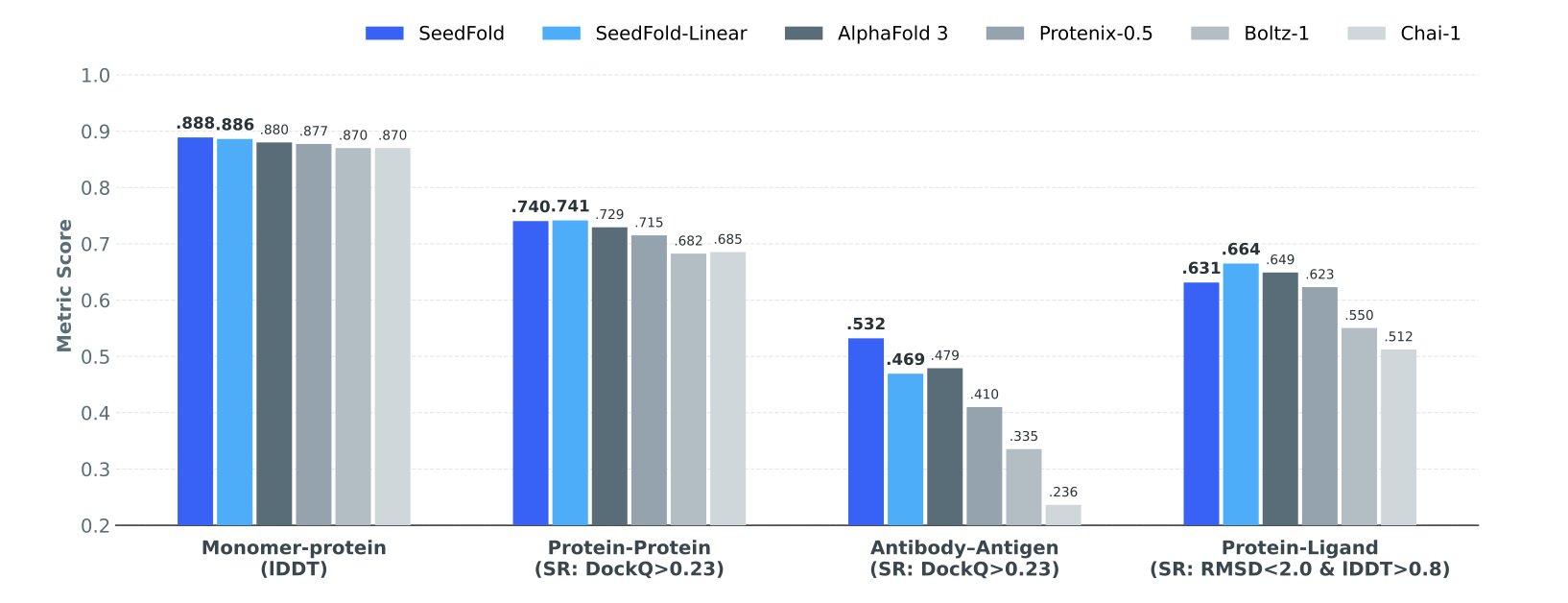

Their thinking was direct: if the old attention algorithm is the bottleneck, replace it. They designed a new linear triangular attention mechanism. This new algorithm reduces the computational complexity from cubic to quadratic. That’s a huge improvement. For example, analyzing a large molecule used to be like examining all possible relationships between every group of three nodes in a network—a massive task. Now, you only need to look at the relationships between pairs of nodes. This opened the door for “brute force” scaling of the model.

With a more efficient algorithm, the next question was how to make the model bigger. The traditional approach is to “stack depth” by adding more network layers. But the SeedFold team found a different path: scale horizontally by increasing the width. They chose to widen the model’s Pairformer module.

This makes sense. In structure prediction, the most critical information is hidden in the pairwise interactions between amino acid residues. Widening the Pairformer module is like giving the model more parallel channels to process and encode these complex pairwise relationships simultaneously. Compared to passing information through a very long chain (depth), this “wide” structure is better at capturing the essence of the problem.

Of course, a powerful model isn’t enough; you need enough data to feed it. Experimental data is always scarce, so what did they do? The researchers used a method called distillation. They used AlphaFold2 as a teacher to generate a massive dataset of 26.5 million samples. It’s like having a novice learn from a master through a huge number of case studies. Even though it’s not firsthand knowledge, it’s enough for the model to grow quickly and gain strong generalization capabilities.

And the results did not disappoint. On FoldBench, the industry-standard benchmark, SeedFold outperformed AlphaFold3 on several tasks, especially in antibody-antigen interactions and protein-RNA interactions. Its linear variant also performed very well on protein-small molecule interaction prediction, a key area of interest for drug developers.

Training a model of this scale is not easy. The researchers also shared their experience, such as using a two-stage training strategy and employing a longer warm-up period and a lower initial learning rate in the early stages to ensure the behemoth could converge stably. This is valuable experience that only comes from hands-on model training.

The work on SeedFold shows us a very clear path: by optimizing algorithms and scaling strategies, we can achieve real performance gains with bigger models and more data. It’s simple, but effective.

📜Title: SeedFold: Scaling Biomolecular Structure Prediction

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.24354

4. A New Framework for Molecular Discovery: Generate Then Optimize

In the vast world of molecular discovery, we’re often looking for a needle in a haystack. Traditional AI methods often mix “imagining new molecules” and “evaluating if the molecule is good,” forcing the model to be both a creative director and a quality inspector. The result is a complex and inefficient process.

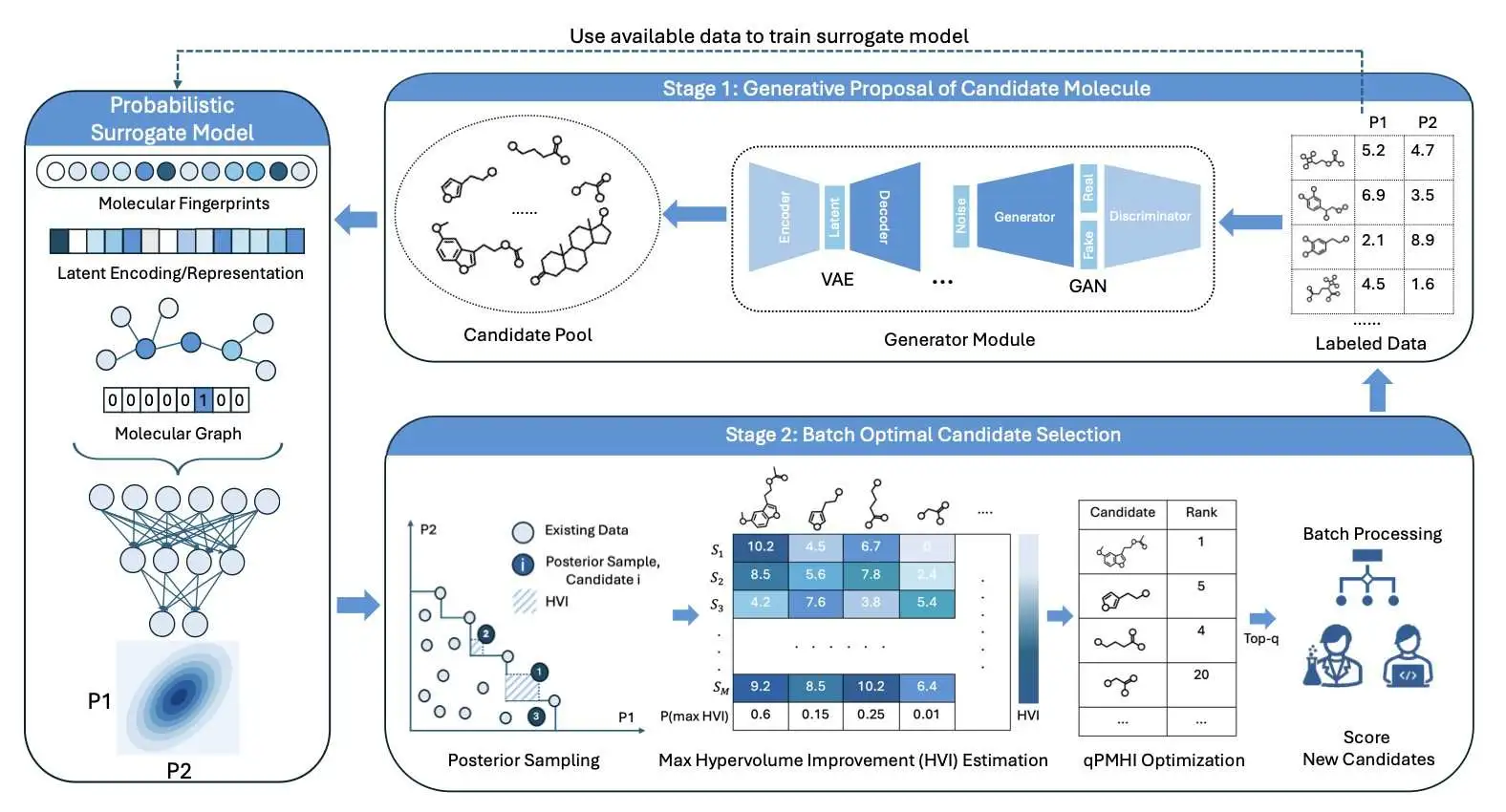

The authors of this paper propose a more streamlined approach: generate-then-optimize.

The idea sounds simple, but it’s very effective. First, a generative model is allowed to run wild, creating a huge and diverse library of candidate molecules. This is like a brainstorming session where all ideas are welcome without judgment.

Second, a separate optimization algorithm is used to select the most promising candidates from this massive “idea library” for the next stage of evaluation (like wet lab experiments or expensive computational simulations).

The core advantage of this two-step strategy is decoupling. The generative model only creates, and the optimization algorithm only selects. Each has its own job. This makes the whole system modular. You can easily swap in any generative model or property predictor you like, as if changing Lego bricks, without worrying about affecting the entire system.

So, here’s the key question: how do you efficiently select an entire batch of the most promising candidates from thousands of molecules?

Picking them one by one is too slow. Ideally, you want to use parallel computing or high-throughput experimental platforms to test dozens or even hundreds of molecules at once. But picking an “optimal set” that is both promising and diverse is a very complex combinatorial optimization problem, and it’s computationally expensive.

To solve this bottleneck, the researchers designed a clever acquisition function called qPMHI. Here’s how it works: instead of trying to solve that complex optimization equation, it directly calculates the probability that each candidate molecule will improve our current set of best solutions. Then, it just ranks the molecules by this probability.

Finally, you just take the top-ranked batch of molecules from the list. qPMHI turns a difficult optimization problem into a simple sorting problem, greatly improving the efficiency and scalability of batch selection.

To test their method, the researchers applied it to a real-world chemistry problem: finding better organic redox molecules for sustainable energy storage. The results showed that, compared to other state-of-the-art methods, their new framework found better-performing and more diverse molecules using fewer queries (which means lower experimental or computational costs).

For people on the front lines of drug discovery or materials science, this method is very appealing. It directly addresses a core pain point in molecular discovery: how to explore the vast chemical space most efficiently with limited resources. This “generate-then-optimize” approach, combined with the batch selection algorithm, provides a very practical solution for accelerating the discovery of new molecules using high-throughput platforms.

📜Title: Generative Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization with Scalable Batch Evaluations for Sample-Efficient De Novo Molecular Design

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.17659v1

5. Reverse-Engineering AlphaFold3? SeedProteo Designs Entirely New Proteins

When designing proteins, especially in drug development, our goal is clear: to create a new protein on demand that can bind to a specific target. This is like sculpting at the atomic scale. You not only need to get the shape right, but you also need to choose the right material (amino acid) for each position. Traditional methods often have to simplify the problem, for instance, by only considering the protein’s backbone atoms and ignoring the side chains. But the details matter, and precise design at the all-atom level is the real challenge.

Recently, a new model called SeedProteo has caught people’s attention because it tackles this hard problem directly.

Reversing AlphaFold3

Anyone in computational science who sees SeedProteo’s architecture will immediately think of AlphaFold3. AlphaFold3’s job is to take an amino acid sequence and predict its 3D structure. It’s a “sequence-to-structure” prediction process.

The researchers behind SeedProteo did something cool: they flipped this process around. They don’t input a sequence. Instead, they start with a collection of randomly distributed, disordered atomic coordinates (or “noise”). Then, using a powerful network similar to AlphaFold3, the model learns how to “denoise” this cloud of atoms, gradually building a plausible, stable 3D protein structure.

This is like restoring a high-definition image from a completely blurry one. But it’s not just restoring; it’s creating. Because it starts from noise, it can create a different, new structure every time. This is the core idea of diffusion models in generative AI.

How to Match the Blueprint with the Building Materials?

Just generating a nice 3D structure isn’t enough. You also need to know which amino acid sequence will build it. This is one of the hardest problems in protein design: sequence-structure consistency. Many models design beautiful-looking structures, but you can’t find a suitable amino acid sequence that will stably fold into that shape.

SeedProteo uses two strategies to solve this.

The first is self-conditioning. In simple terms, this means giving the model hints as it generates the structure. For example, the model first predicts the approximate secondary structure (α-helices, β-sheets, etc.), and then this prediction is fed back into the model as an additional input for the next step. It’s like giving a robot a rough map while it’s exploring. With the map, it’s less likely to get lost and can find the right path more quickly. This approach significantly improves the success rate of generating physically plausible protein structures.

The second strategy is using a Markov Random Field (MRF) module to decode the amino acid sequence. Traditional sequence design methods are often “greedy,” deciding on the amino acid for one position at a time to find a local optimum. This can easily lead you down the wrong path, like playing chess by only looking one move ahead and losing the whole game. The MRF is different. It considers the interactions and dependencies among all amino acids in the entire protein structure at once. Instead of filling in the blanks one by one, it provides a globally optimal sequence solution in one go. This ensures that the entire amino acid chain, as a whole, can best stabilize the 3D structure we designed.

How Did It Do?

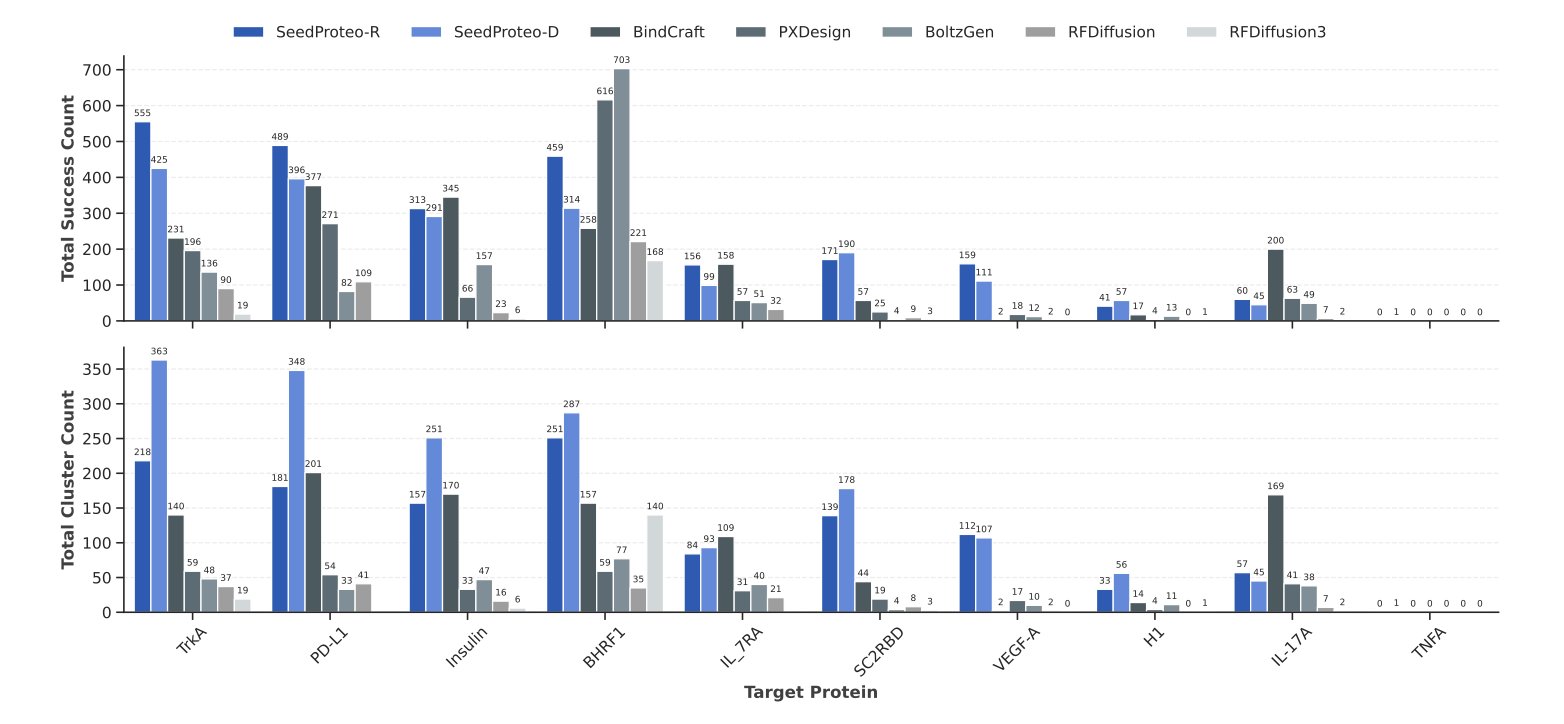

The data shows that SeedProteo performs well. In both unconditional generation (letting the model freely create new proteins) and the more challenging task of designing protein binders, it surpassed some of the current top models.

It’s particularly noteworthy that it maintains a high success rate when growing sequences (up to 1,000 residues) and that the binders it generates are structurally diverse and novel. For drug discovery, these two points are crucial. We need to be able to explore the vast, unknown chemical space. This work provides a powerful tool and a new direction for protein engineering and therapeutic drug development.

📜Title: SeedProteo: Accurate De Novo All-Atom Design of Protein Binders

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.24192