Table of Contents

- A new AI model called GenoME can predict a new cell type’s entire set of gene regulatory activities using only chromatin accessibility data (ATAC-seq) and can simulate the effects of gene mutations directly in the computer.

- Researchers used the self-assembling properties of amyloid proteins and the structural prediction power of AlphaFold to develop an efficient de novo design method that can quickly generate many novel and stable protein structures.

- BindMecNet significantly improves the accuracy and generalizability of binding affinity prediction by forcing the model to learn the mechanisms of atom-residue interactions.

- The B-PPI model, designed specifically for bacteria, uses a protein language model and a cross-attention mechanism to screen protein interactions more accurately and quickly, outperforming older models trained on human data.

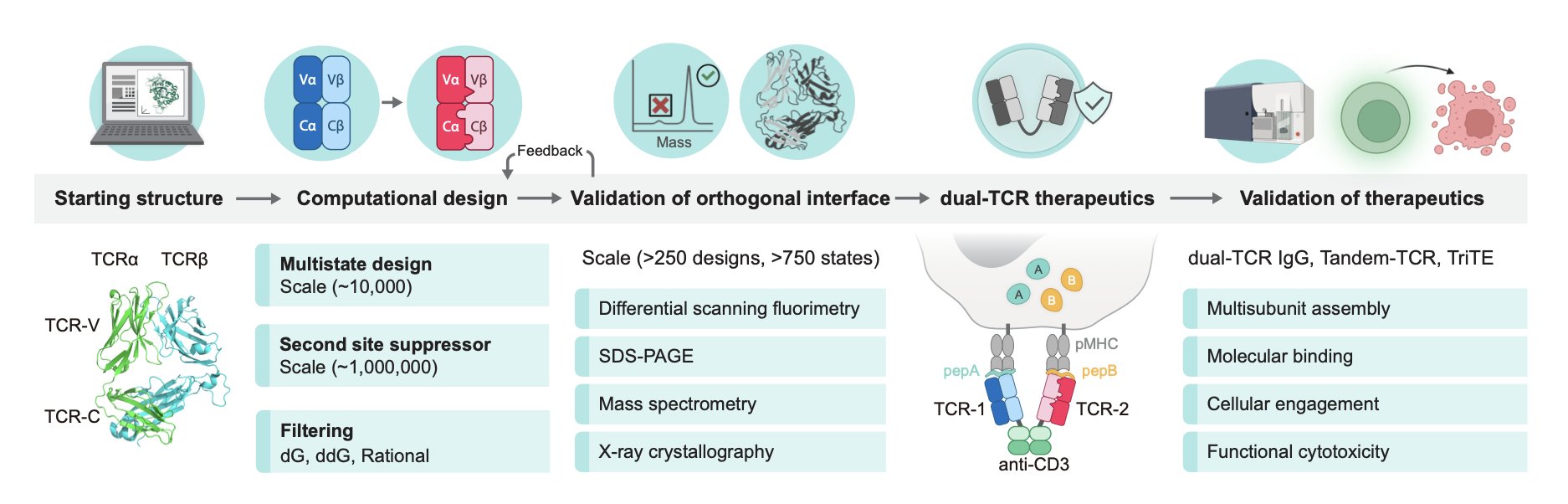

- Through computational design, researchers successfully re-engineered the protein interface of T-cell receptors (TCRs) to force the correct pairing of their α/β chains, paving the way for safer and more effective multi-specific T-cell therapies.

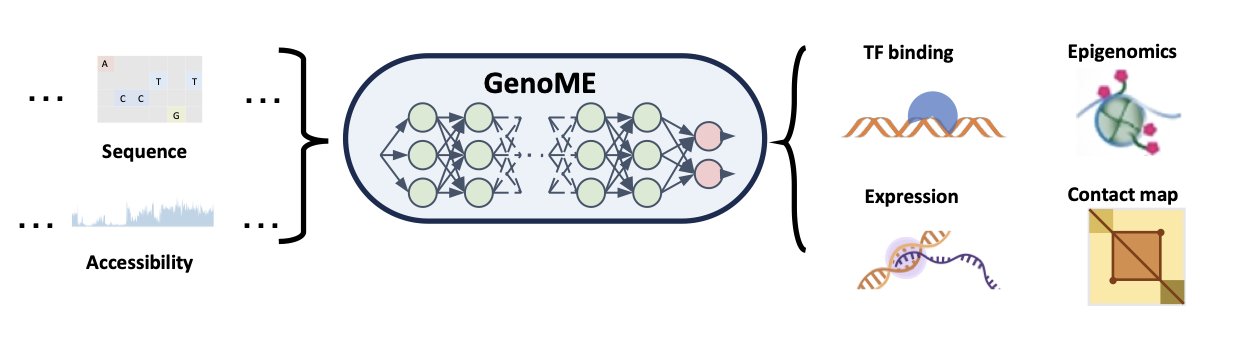

1. GenoME: A Single Model to Predict Gene Regulation in All Cells

In genomics research, we often run into a frustrating problem: models don’t generalize. A model trained to predict gene expression in T-cells is basically useless for neurons. Predicting histone modifications and 3D chromatin structure requires two different toolkits. It’s like trying to fix a car where the engine, transmission, and electrical system each have their own repair manual, and every car brand has a completely different set of manuals. It’s very inefficient.

Now, a new paper introduces the GenoME model, which aims to be the universal “master repair manual” for cars.

How does it work?

The researchers simplified the problem down to two core inputs: the cell’s “hardware”—its DNA sequence—and its “current operating state”—chromatin accessibility (measured by ATAC-seq). You can think of the DNA sequence as all the books in a library and the ATAC-seq data as telling you which books are currently open and available to be read.

GenoME’s architecture is clever, using a Mixture of Experts (MoE) model. You don’t need to overcomplicate it. A traditional neural network is like a general practitioner who knows a little about everything but isn’t an expert in anything. The MoE framework is like a team of specialists in a consultation. It has many “expert” subnetworks, each of which might be particularly good at handling the regulatory logic of a certain cell type, like immune cells or epithelial cells. It also has a “gating network” that first analyzes the incoming ATAC-seq data and decides, “Okay, based on this cell’s features, experts #3 and #5 are the best combination for the job.”

This way, the model not only shares knowledge across different tasks (like predicting gene expression or chromatin structure) but also cleverly applies the regulatory patterns learned from one cell type to a completely new one.

The real highlight: predicting the unknown

The model’s most impressive feature is its ability to generalize. Most AI models perform well on their training set but fail when they encounter data they haven’t seen before. GenoME can take the ATAC-seq data from a cell type it has never “studied” and accurately predict that cell’s gene expression, histone modifications, and a range of other states.

What does this mean for R&D? Suppose we want to study a specific cell from a patient with a rare disease, but we lack the large public datasets needed to train a model for that cell type. With GenoME, we just need to perform ATAC-seq on the patient’s cells to get a pretty good panoramic view of its gene regulation. This opens a new window for personalized medicine.

Doing CRISPR experiments on a computer

Another powerful feature of GenoME is “in silico perturbation.” This essentially gives you the ability to perform gene editing on your computer.

For example, a GWAS analysis finds a strong link between a SNP in a non-coding region and disease risk. We suspect it affects an enhancer’s function, but which gene does this enhancer regulate? Verifying this with traditional experiments takes a long time.

Now, you can directly “edit” this SNP in the GenoME model, or even “knock out” the entire enhancer sequence, and then have the model run a new prediction. If the results show a significant change in the expression of a specific gene, you’ve found a solid causal link. This can help us quickly screen and validate potential drug targets or functional genetic variants, shortening weeks of lab work to just a few minutes.

GenoME isn’t just another prediction model. It provides a framework that allows us to explore and understand the complex logic of the human genome’s regulation in a way that approaches causal inference. For anyone in drug development, functional genomics, or precision medicine, this is certainly a powerful tool to watch.

📜Title: GenoME: a MoE-based generative model for individualized, multimodal prediction and perturbation of genomic profiles

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.28.696482v1

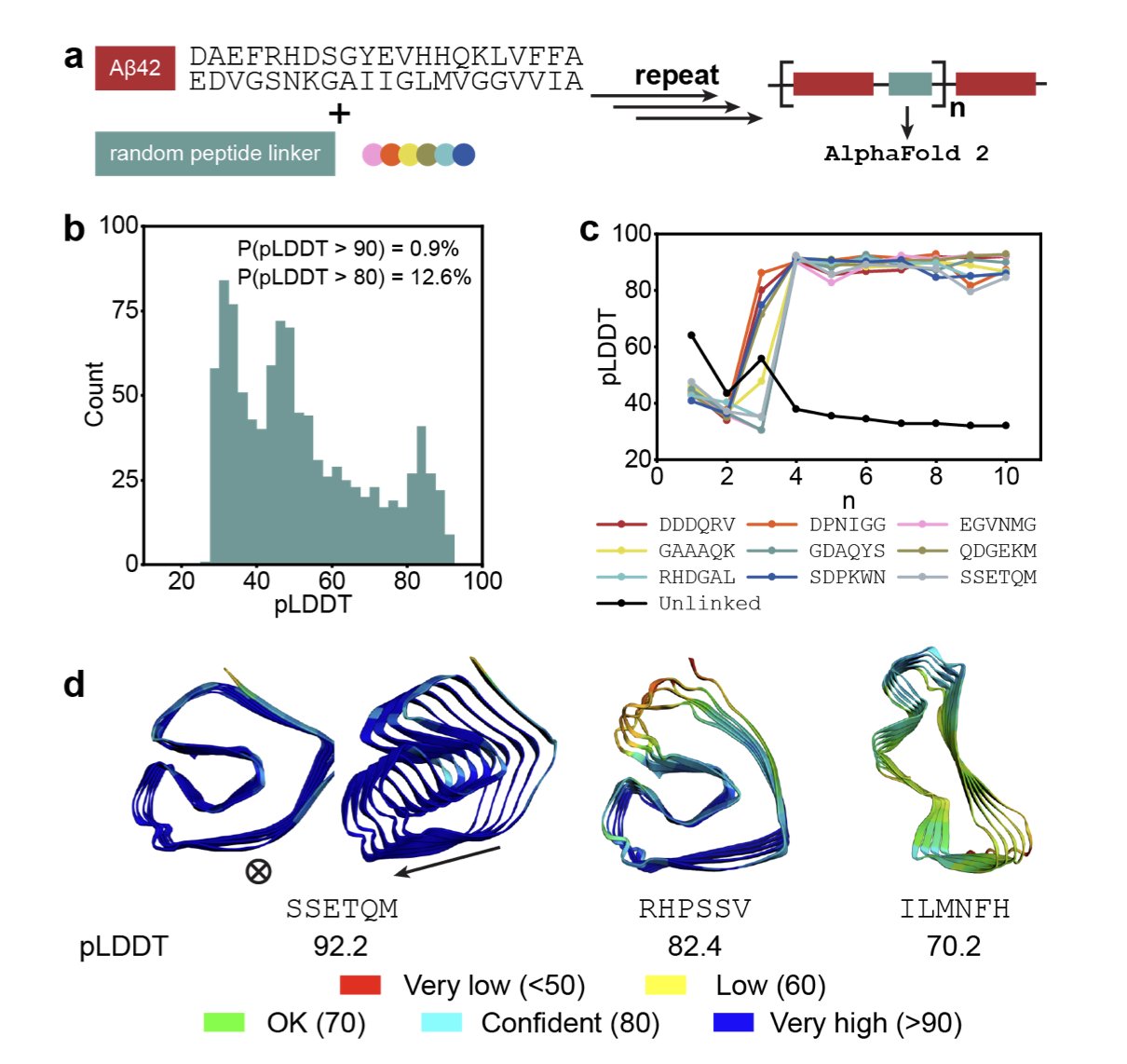

2. A New Use for AlphaFold: Designing Novel Proteins with Amyloid Building Blocks

In drug development, de novo protein design has always been a tough nut to crack. The usual goal is to design a protein that performs a specific task, like binding to a target. But the process is slow and has a high failure rate. The authors of this paper took a different approach: what if we ignore function for a moment and, purely for “fun” or “curiosity,” just try to create some brand-new, structurally stable protein backbones?

Their idea is clever, and even a bit counterintuitive. They chose amyloid β42 as their base material—the same “bad protein” that forms plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. This protein has a special characteristic: it loves to self-aggregate, forming stable β-sheet structures. The researchers saw potential in this “structural stability.”

Here’s how it works:

First, they took two Aβ42 units and treated them as “building blocks.”

Second, they connected these two blocks with a randomly generated hexapeptide linker. This is like tying two blocks together with a short piece of string.

Third, they fed this combined sequence into AlphaFold 2. They didn’t ask, “What can this protein do?” Instead, they asked, “Can this sequence fold into a stable 3D structure?” If AlphaFold returned a high-confidence prediction, it meant the model believed the structure was stable.

The results were surprisingly good. With completely random linkers, over 12% of the designs were given a high score by AlphaFold. For de novo design, this is a very high “hit rate.”

Next came the more interesting part: computational evolution

The researchers didn’t stop with the first batch of stable structures. They introduced a genetic algorithm to simulate “evolution” inside the computer.

They applied small “segmental mutations” to the successful structures and then used AlphaFold to screen them again, keeping the mutants that formed better, more stable structures. This process was repeated over and over, just like natural selection, but many times faster and entirely within a computer.

Through this method, they “evolved” a series of new proteins with diverse structures. As shown in the image above, these proteins have a variety of folding patterns, including β-solenoids and antiparallel β-sheets. This is equivalent to creating a whole new library of protein structures from scratch.

Are these designs reliable?

AlphaFold’s predictions are, after all, just predictions. To verify whether these new proteins are also stable in the real physical world, the researchers ran Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. An MD simulation is like a stress test for molecules inside a computer, seeing if they fall apart in a simulated physiological environment.

The results once again confirmed the robustness of the method. Most of the de novo designed proteins maintained their predicted 3D structures in the simulation, showing they are not just computationally sound but also physically stable.

What does this mean for drug developers? It means we have a new and efficient tool for generating protein scaffolds. We can first use this “curiosity-driven” method to quickly and cheaply generate a huge number of novel and stable protein backbones. Then, using these backbones as a base, we can design functional domains—like adding a loop that can bind to a target—to turn them into peptide drugs or enzymes.

This changes the old “function-first” design paradigm to a “structure-first” strategy. Instead of first having a target and then looking for an arrow, we can now build a massive quiver full of all sorts of unseen “arrows,” and then pick and polish the right one when we need it. This opens a new door for developing novel peptide drugs and functional biomaterials.

📜Title: Curiosity-driven de novo protein design via polymerized amyloids

🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-tbfjt

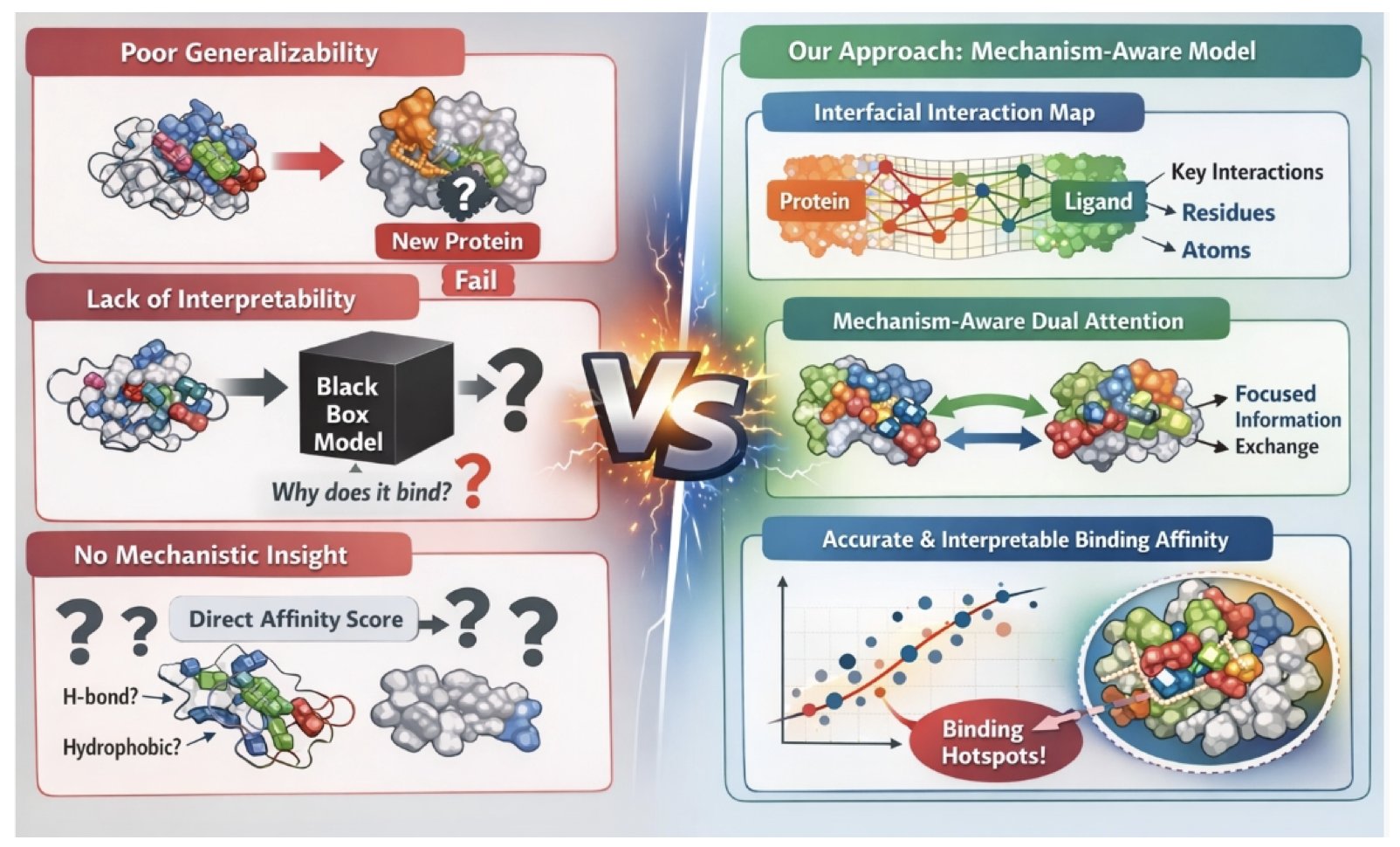

3. Predict the Forces First, Then Score: A New Approach for AI in Affinity Prediction

In drug discovery, predicting the binding affinity between a molecule and a protein target has always been one of the core problems in our field. Traditional docking scoring functions have been used for decades, and everyone knows their limitations. In recent years, deep learning models have emerged one after another, posting impressive numbers on various datasets, but we’ve always had a doubt: do these models truly “understand” the interactions between molecules? Or are they just “black boxes” that are overfitted to a specific dataset?

A recent work called BindMecNet offers a new way of thinking. The authors didn’t just ask the model to guess the final binding affinity value. They gave it a prerequisite task: you first have to tell me which atom on the small molecule interacts with which amino acid residue on the protein.

This is like teaching a student to solve a complex physics problem. You don’t just let them give the answer; you make them draw the force diagram first. The core of BindMecNet is this “diagram-drawing” step, which is its “Interfacial Interaction Prediction Module.” This module generates a detailed interaction map, pinpointing which atom-residue pairs are the “key players.”

Then, the model uses this map, through a “mechanism-aware dual attention module,” to calculate the final binding affinity. The benefit of this is obvious. It introduces a strong “mechanistic inductive bias” into the model. In other words, the model’s prediction is no longer just pattern matching; it’s anchored to real physical and chemical interactions. The model’s attention is forced to focus on the areas where interactions actually happen, rather than learning spurious correlations.

What’s even more valuable is their training strategy. Anyone working in computational fields knows that high-quality crystal structure data, like what’s in PDBBind, is precious but limited. In real-world projects, we often deal with protein structures predicted by tools like AlphaFold, and these structures are not as perfect.

BindMecNet uses a two-stage training method. The first step is to pre-train on a high-quality dataset like PDBBind. This is like letting the model build a solid foundation of physical principles in an “ivory tower.” The second step is to fine-tune it on more challenging datasets like DUD-E and LNCaP, which may even include predicted structures. This is like taking a graduate with a strong theoretical background and throwing them into a real project to teach them how to handle all kinds of imperfect situations.

This training approach significantly improves the model’s ability to generalize. The results prove it. BindMecNet not only achieved top-tier performance on the PDBBind core test set but also clearly outperformed other deep learning models on the more challenging DUD-E benchmark and LNCaP dataset. This shows it’s not just a “good test-taker” on a specific exam but has the ability to solve new problems.

For medicinal chemists, the most attractive feature of this model is its interpretability. The interaction map it outputs is essentially a “binding hotspot map.” We can directly see which group on the molecule is contributing the most to the binding energy and through which type of force (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, etc.). This is invaluable for subsequent molecular optimization and rational design.

Ablation studies also confirmed that both the pre-training step and the explicit interaction prediction loss function are critical for the model’s performance and generalizability. Removing either part leads to a drop in performance.

BindMecNet’s design philosophy moves AI one step closer from being a simple “scorer” to an “analytical tool” that provides insight. It tries to find a balance between computational efficiency and predictive power, making the AI’s “thinking” process more aligned with the intuition of human chemists.

📜Title: A Mechanism-Aware Dual Attention Deep Model for Molecular-Protein Binding Affinity Prediction with Enhanced Generalizability and Interpretability

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.29.696866v1

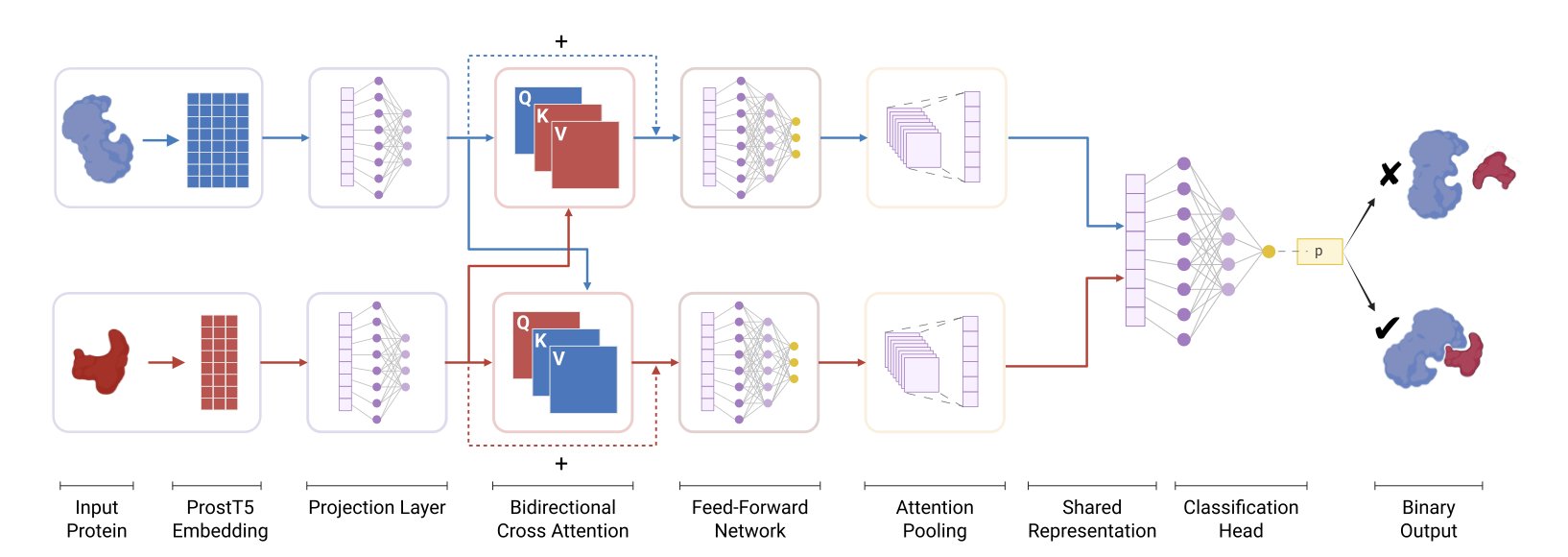

4. Stop Using Human PPI Models for Bacteria. Try B-PPI.

Colleagues who study bacteria have probably had this experience: you’re trying to find the interaction partner of a key protein, so you excitedly plug the sequence into a popular online prediction tool, only to get a list of unreliable candidates. What went wrong? Many of these tools are trained on human protein data. Asking them to make predictions for bacteria is like asking someone who only speaks English to translate German—the results are not going to be great.

The B-PPI project is here to solve this problem. The researchers started from scratch and built a computational tool specifically tailored for bacterial systems.

Here’s how it works.

First, the model needs a way to “read” proteins. The researchers used embeddings from ProstT5, a large language model for proteins. You can think of ProstT5 as an expert who is fluent in the “language” of proteins. It has read a vast number of protein sequences and understands not just the order of amino acids but also the hidden structural and functional information within the sequence. This way, what’s fed into the model isn’t just a dry string of letters but a much richer feature vector.

Next, the model needs to determine if two proteins are a “good match.” For this, it uses a mechanism called Bidirectional Cross-Attention. This mechanism is quite clever; it allows the model to simulate a process of “mutual inspection” when comparing two proteins. The model simultaneously pays attention to which regions of protein A are most important to protein B, and which regions of protein B are most important to protein A. It’s like two people shaking hands—both instinctively focus on the other’s hand and arm to coordinate the movement, not their whole body. This way, the model can precisely locate the interface regions where an interaction is most likely to occur.

A good model needs good data. The researchers built a new bacterial PPI database, B-PPI-DB, containing over 200,000 interaction pairs. Crucially, they didn’t use the common 1:1 positive-to-negative sample ratio found in academia. Instead, they used a more realistic 1:10 ratio. In a real cell, any two random proteins are unlikely to interact. Training on this kind of “needle-in-a-haystack” dataset forces the model to learn to identify truly meaningful signals instead of just guessing.

The results showed this approach was worthwhile. On bacterial datasets, B-PPI’s performance far surpassed that of TT3D, a state-of-the-art model trained on human data, especially on key metrics like AUPRC and F1-score. It’s also faster, which means we can use it for large-scale, proteome-wide screening.

To test the model’s adaptability, the researchers also applied it to an external dataset for H. pylori. With just a little fine-tuning, B-PPI was able to adapt well to the new species. This suggests it has the potential to become a foundational framework for predicting PPIs across various bacteria.

Of course, the model isn’t perfect. Its predictive power is limited by the coverage and potential biases of its training data. But for drug discovery scientists, B-PPI is a powerful filter. It can help you narrow down a list of thousands of possibilities to a reliable list of candidates worth investing time and resources in for wet lab validation. This can greatly speed up our research.

📜Title: B-PPI: A Cross-Attention Model for Large-Scale Bacterial Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.23.696145v1

💻Code: https://github.com/bursteinlab/B-PPI.git

5. Biggest Hurdle for Dual TCR Therapy Solved? Computational Design Creates ‘Orthogonal’ T-Cell Receptors

When developing T-cell therapies, especially those that aim to make a single T-cell recognize two different tumor antigens, we always run into a major problem: TCR chain mispairing.

A natural T-cell receptor (TCR) is made of one α chain and one β chain. If you want a T-cell to recognize two targets, you need to introduce two different TCR sets: TCR-1 (α1/β1) and TCR-2 (α2/β2). In theory, they should assemble correctly. But in reality, these four chains combine randomly, creating unwanted mispaired combinations like α1/β2 and α2/β1. These mispaired TCRs are not only useless but can also recognize self-tissues, leading to dangerous autoimmune reactions. This problem has been a major roadblock in developing dual-target TCR-T therapies.

Instead of relying on luck-based screening, the authors of this paper acted like architects, using a computational tool (Rosetta) for precise design. Their idea was simple: redesign the binding interface between the α and β chains so that α1 would only “hit it off” with β1, and α2 would only pair with β2.

Here is how they did it.

First, they focused their modifications on the constant domains of the TCR. This was a smart choice because the variable domains are responsible for recognizing antigens. By only modifying the constant domains, their design can serve as a “universal chassis” that can be adapted to TCRs with different targets, making it widely applicable.

Next, they used a multistate design algorithm to introduce mutations at the interface where the α and β chains meet. This process is like designing unique shapes and charges for puzzle pieces. For example, they might introduce positive and negative charges on one TCR pair’s interface to create attraction, while introducing two positive charges on another pair to make them repel each other. This way, α1 is designed to bind tightly only with β1 and to repel β2.

A design is not enough; it has to be validated. The authors screened over 250 design variants and tested them experimentally. The results were excellent. Using mass spectrometry, they found that the correct pairing rate reached about 95%. They then used X-ray crystallography to determine the protein structure, confirming at the atomic level that the newly introduced mutations indeed acted as a “lock,” forcing the correct pairing.

To demonstrate the practical value of this design, they took it a step further and built a trispecific T-cell engager (TriTE). This molecule has three “heads”: two heads that each recognize a different cancer-testis antigen, and a third head that binds to the CD3 molecule on the surface of T-cells, “pulling” them in to kill the tumor.

The results showed that the TriTE molecule performed exceptionally well. When tumor cells expressed both antigens, its killing effect was strongest, with an EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) as low as 380 fM. This is an extremely low concentration, indicating high potency, which is thanks to the avidity effect from dual-target binding. Even when tumor cells expressed only one of the antigens, it still maintained high activity.

This work provides a reliable engineering platform. It uses a computation-first approach to solve a fundamental but critical engineering challenge in multi-specific T-cell therapy. This means that in the future, we can develop “dual-target” or even “multi-target” immunotherapies that are safer and more effective against tumor heterogeneity.

📜Title: Computational Design of Orthogonal TCR α/β Interfaces for Dual‐TCR Therapeutics

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2026.01.02.697397v1