Table of Contents

- Researchers combine machine learning and robotics to create a high-throughput platform for antibody formulation, efficiently screening and optimizing for stability, viscosity, and diffusivity.

- Researchers merge quantum circuits with neural networks to design more expressive “quantum fingerprints” for molecules, improving the accuracy of identifying active molecules when data is sparse.

- For the first time, researchers use a quantum computer to successfully simulate the electronic structure of a protein, opening a new path for solving complex biological problems in drug development.

- A new AI can interpret 1D NMR spectra like a language, directly outputting molecular structures and marking a key step toward automated structure elucidation.

- SynCraft teaches a large language model to think like a senior chemist, optimizing molecules through precise, atom-level edits instead of brute-force regeneration.

1. AI-Powered Antibody Formulation Development to Accelerate Biologic R&D

If you’ve worked on antibody drug formulation, you know how much of a grind it is. We face a massive, unknown design space filled with various excipients, pH values, and buffers, all interacting with each other. The goals are also numerous: the drug needs to be stable, have low viscosity for injection, and maintain its activity. Traditional methods are like fumbling in the dark, relying on a researcher’s experience and a lot of trial and error. It’s slow and expensive.

The authors of this paper wanted to solve this problem. Their idea is straightforward: let robots and AI do the heavy lifting.

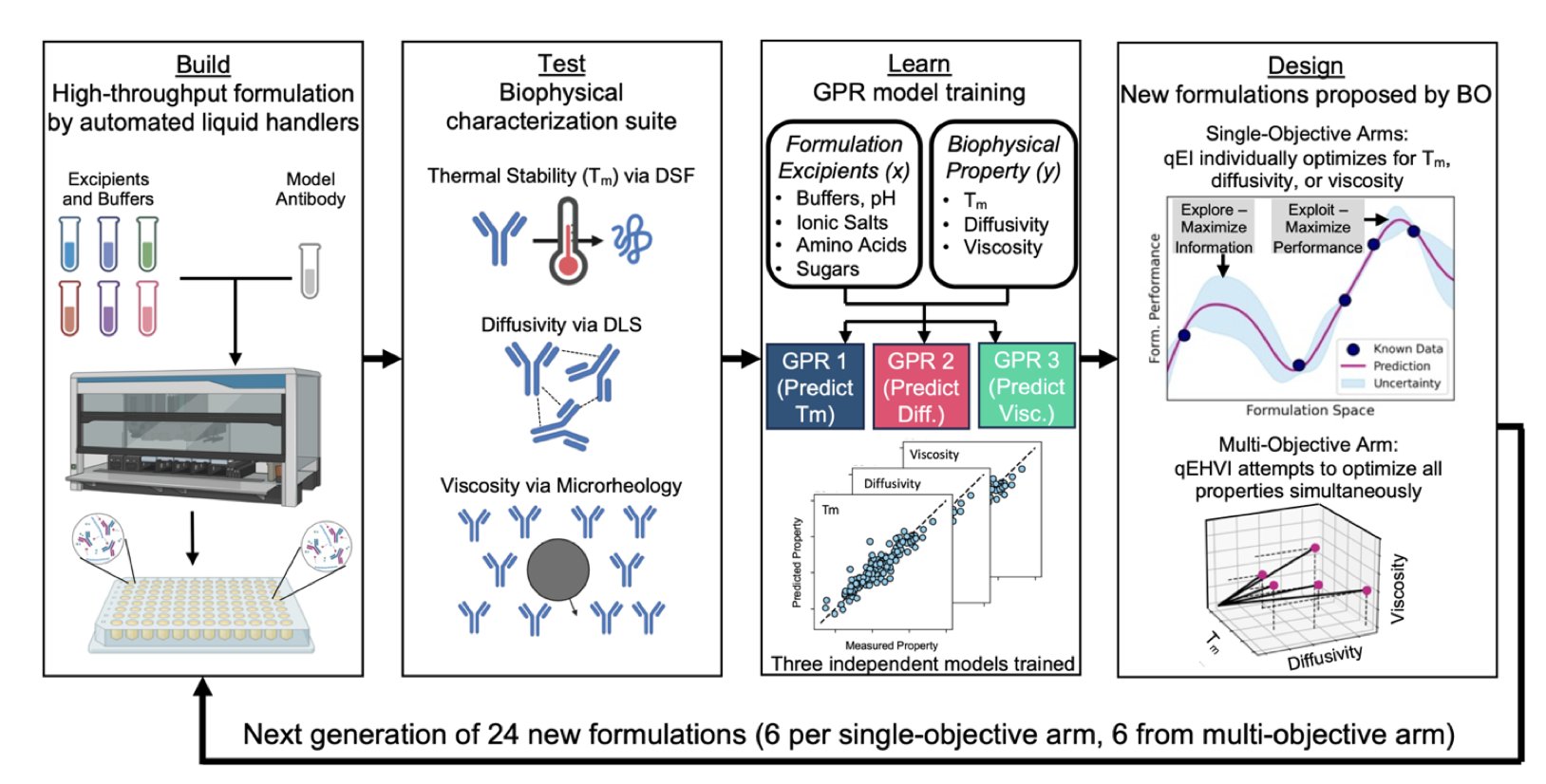

They built a fully automated “Design-Build-Test-Learn” (DBTL) workflow.

- Design: First, a machine learning algorithm, specifically Bayesian Optimization, proposes a batch of promising formulation combinations. Unlike guessing at a formulation, the algorithm uses existing data to predict which new combinations are most likely to succeed.

- Build: Next, an automated robotics system takes over, precisely executing the formulation instructions by mixing the various solutions to prepare samples for testing. This process eliminates tedious manual pipetting and greatly improves speed and accuracy.

- Test: The robot then automatically characterizes a series of biophysical properties of the samples, such as melting temperature (Tm), viscosity, and diffusivity.

- Learn: Finally, the test data is fed back into the machine learning model. The system uses an Active Learning strategy, where the model analyzes the new data, updates its understanding, and then more intelligently designs the next round of experiments. It focuses its efforts on exploring the most informative and promising “uncharted territories.”

The entire process forms a closed loop that iterates and optimizes itself round after round.

How were the results? The data speaks for itself. After just two rounds of active learning, the formulation performance showed a visible improvement. The average diffusion coefficient increased by 22.2%, average viscosity decreased by 13.7%, and the average melting temperature (representing thermal stability) increased by 1.43°C. In formulation development, every small improvement is hard-won, so this is a solid result.

What’s more valuable is that they also introduced explainable AI, specifically SHAP values. This tells us how much each excipient contributed—positively or negatively—to the final optimal formulation. This transforms the AI from a “black box” that just gives answers into a “teacher” that can communicate and share knowledge. We not only get the formulation but also understand why it works, which is crucial for building knowledge and guiding future projects.

Of course, one of the biggest challenges in formulation is balancing multiple conflicting objectives. For instance, an excipient that improves stability might also increase viscosity. This work also performed well in multi-objective optimization, achieving a normalized hypervolume gain of 73.3%. This metric sounds complex, but it basically means the AI found a large “sweet spot” where formulations perform well across multiple dimensions like stability and viscosity. This gives developers a rich list of candidates, not just a single “take-it-or-leave-it” answer.

Overall, this work provides a new paradigm for biologic drug formulation. It shows how automation and intelligent algorithms can be used to move a field that has traditionally relied on extensive manual labor and time, making drug development faster and more precise. The next step is to apply this method to more antibody molecules and higher-concentration formulations, which will be the real test of the technology’s strength.

📜Title: Automation and Active Learning for the MultiObjective Optimization of Antibody Formulations 🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-rxq1t

2. Quantum Computing for Virtual Screening: A New Engine for Drug Discovery

In the early stages of drug discovery, we’re looking for a needle in a haystack—trying to find promising candidate compounds from libraries of millions or even billions of molecules. Virtual Screening is our sonar, helping us narrow the search.

Traditional methods, like similarity searches based on molecular fingerprints, are like taking a 2D snapshot of a molecule; the amount of information is limited. Now, some researchers want to take a “quantum CT scan” of molecules to see if they can get a richer, more dimensional representation.

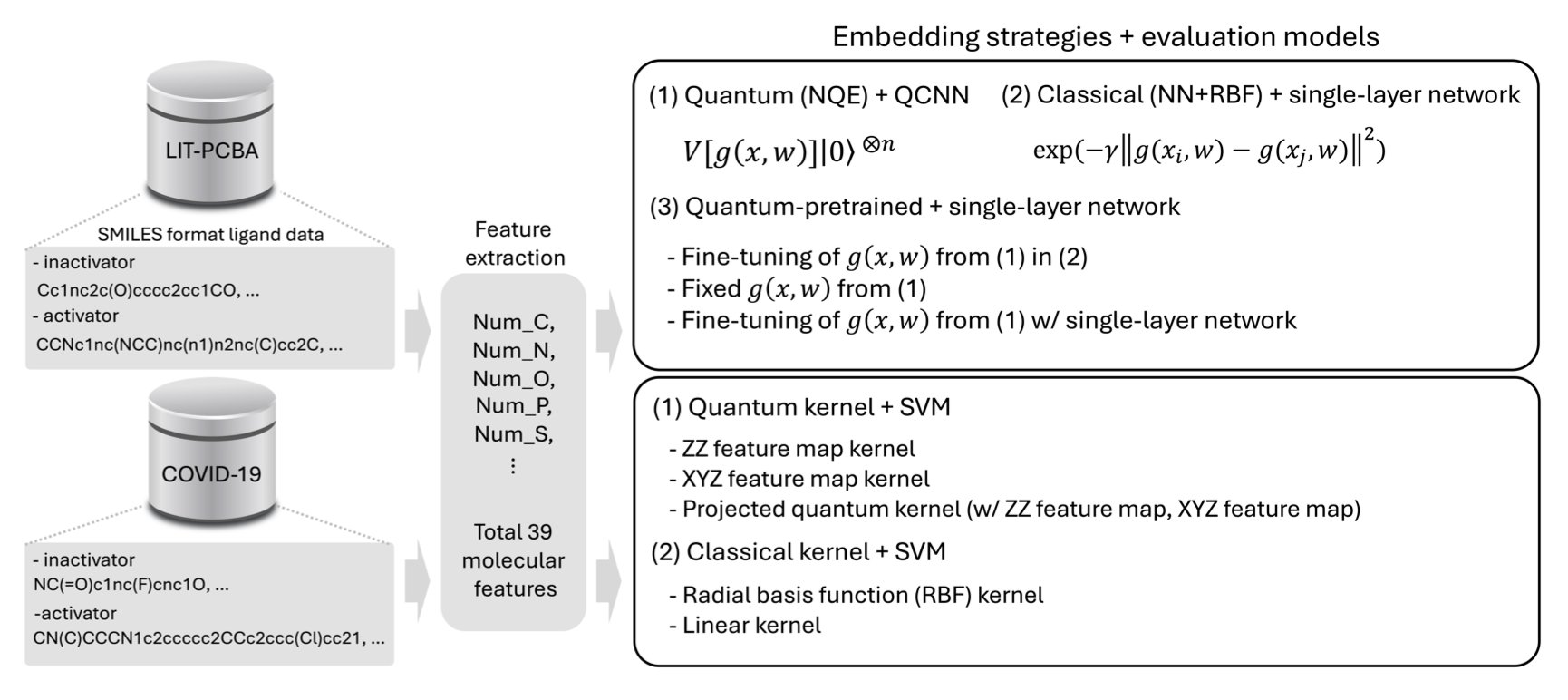

The core idea of this paper is to “encode” molecular information onto quantum bits (qubits), forming what is called a Quantum Embedding. A classical computer uses 0s and 1s to represent information, but a qubit can be both 0 and 1 at the same time and can be entangled with other qubits. This means a quantum embedding can capture more complex and subtle relationships within a molecule’s structure using fewer resources.

But what’s the best way to encode this information? That’s the highlight of this work. They propose a method called Neural Quantum Embedding (NQE). You can think of it as a calibration process. It uses a mathematical tool called kernel-target alignment to continuously adjust the parameters of a quantum circuit. The goal is clear: to make the quantum states of active molecules and inactive molecules as far apart as possible in space. This way, a subsequent classification model, like a support vector machine (SVM), can more easily draw a clear line to separate the “good molecules” from the “bad ones.”

Let’s look at the data. The researchers validated their idea on two public datasets, LIT-PCBA and COVID-19. The results showed that both pure quantum and hybrid quantum-classical models performed better than traditional classical methods. The advantage of the quantum approach was particularly clear in situations common to drug discovery, such as when data is limited or active molecules are rare (class imbalance). This is important because in many early-stage projects for new targets, we often only have a handful of known active molecules.

Interestingly, they also performed a sort of “dimensional reduction” trick. They found they could first use NQE to train a neural network to learn how to perform quantum embeddings, and then “transplant” this trained network for use on a classical computer. The performance of this “quantum-pretrained” model was better than that of a model trained directly on a classical computer. This gives us a very practical path forward: while today’s quantum computers are not yet powerful enough, we can use their principles to enhance our existing classical computing tools.

So, can we use this in our projects right away? Probably not yet. Current quantum computers are still in their infancy, with high noise and few qubits. But this work points to a new direction: quantum computing isn’t just a mathematical toy for factoring numbers; it could fundamentally change how we understand and represent molecules. It offers a completely new “language” to describe chemical structures. The next step is to see what molecular features these quantum “fingerprints” are capturing that we previously overlooked, and how to design more hardware-friendly quantum circuits. There’s a long way to go, but this is definitely a step worth watching.

📜Title: Optimizing Quantum Data Embeddings for Ligand-Based Virtual Screening 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.16177v1 💻Code: https://github.com/Jungguchoi/Optimizing-Quantum-Data-Embeddings-for-Ligand-Based-Virtual-Screening

3. Quantum Computer Simulates a Protein for the First Time. A New Era for Drug Discovery?

In drug development, we are always dealing with molecules. To accurately predict how a drug molecule will bind to a target protein, the most fundamental approach is to precisely calculate their electronic structures. But this is very difficult. Classical computational chemistry methods, like Density Functional Theory (DFT), often lack sufficient accuracy. More precise methods, like Coupled Cluster theory, have computational costs that explode exponentially with system size, making it nearly impossible to handle a protein with a few hundred atoms.

This paper finally applies quantum computing to a real protein.

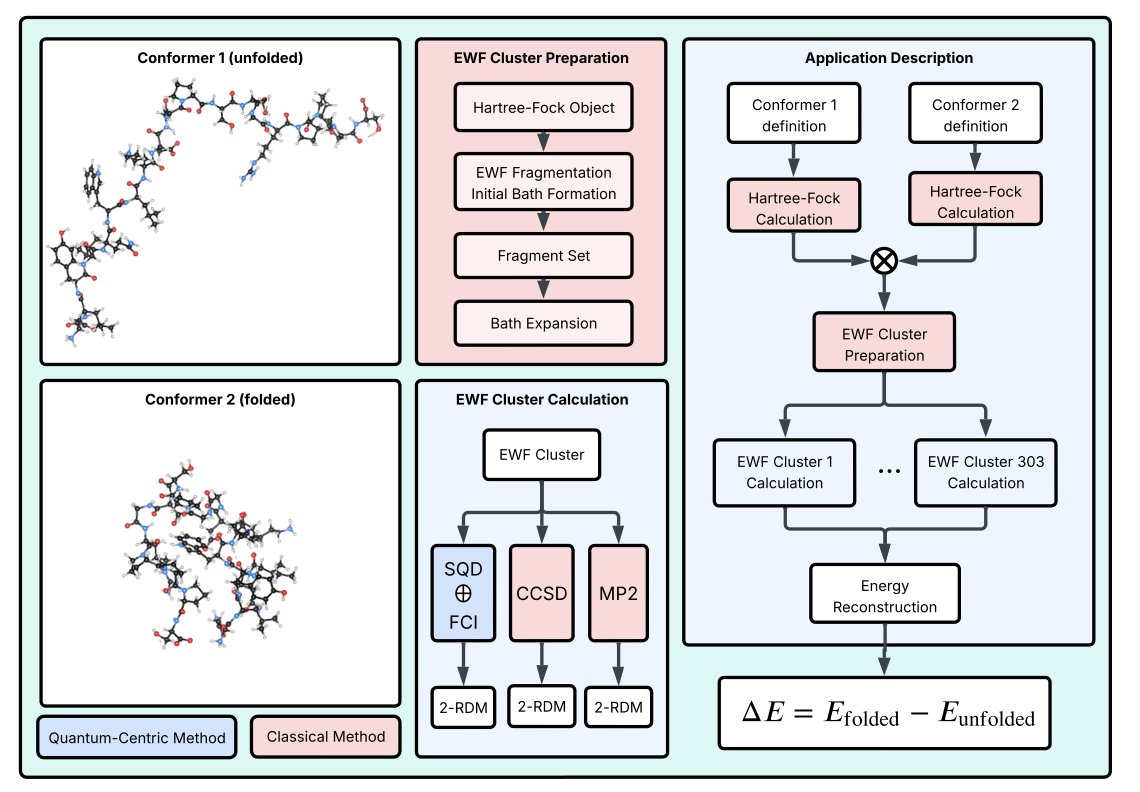

The study’s target was Trp-cage, a tiny protein with only 20 amino acids. Though small, it has all the essential features and is a classic model for studying protein folding. The researchers’ approach was clever. They didn’t try to have the quantum computer tackle the entire protein at once. That’s not realistic with current technology.

Instead, they used a “divide and conquer” strategy.

First, they used a fragmentation method called Wave function–based Embedding (EWF). You can think of this as breaking down a complex Lego model into smaller components. For the simple, chemically uncomplicated “components,” they used a classical method called Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) on a regular computer. This method is very accurate but only works for small systems.

The real challenge lay in the most chemically complex and critical “components,” such as the hydrophobic core where the tryptophan residue is located. Here, the interactions between electrons are extremely complex, and classical computers struggle to calculate them. This is where the quantum computer came in.

They used a technique called Sample-based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD). It works like this: the quantum hardware explores all possible arrangements of electrons within this complex fragment and “samples” the most likely configurations. Quantum computers are best at handling this kind of exponentially complex search problem.

After obtaining these key electron configuration samples, the job was handed back to the classical computer. It post-processed the samples to remove noise and errors from the quantum hardware and then calculated the final energy.

The entire workflow is like an efficient hybrid team: the classical computer handles routine tasks and final data integration, while the quantum computer tackles the core challenge.

So what were the results? They used this hybrid workflow to calculate the energies of the Trp-cage in both its folded and unfolded conformations. The results showed that the method could accurately distinguish the energy levels of these two states, which is consistent with known experimental and classical computational results. This demonstrates the method’s effectiveness. It’s not just a toy problem on a toy molecule; it can solve problems with real biological significance.

Of course, we are still a long way from using quantum computers to design drugs. Current quantum computers are noisy and have a limited number of qubits. But this work is a milestone. It shows a clear and viable path for how to use existing, imperfect quantum hardware to solve problems that are out of reach for purely classical computation. It’s like the invention of the first car. It wasn’t fast and it broke down a lot, but it proved that the concept of the internal combustion engine was viable. This paper does the same thing. It lays the groundwork for using quantum computing to accurately simulate complex biological processes like enzyme catalysis and drug-target interactions in the future.

📜Title: Molecular Quantum Computations on a Protein 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.17130v1

4. AI as a Chemist: Deducing Molecular Structure from Only 1D NMR Spectra

Anyone who does synthesis knows how mentally taxing it is to determine the structure of an unknown compound. Getting an NMR spectrum is like being handed a treasure map. The chemical shifts, splitting patterns, and coupling constants are all clues that you have to piece together with experience and logic to arrive at the final molecular structure. The process is both a science and an art, but frankly, it’s time-consuming.

Now, a new paper presents an interesting idea: let an AI do it.

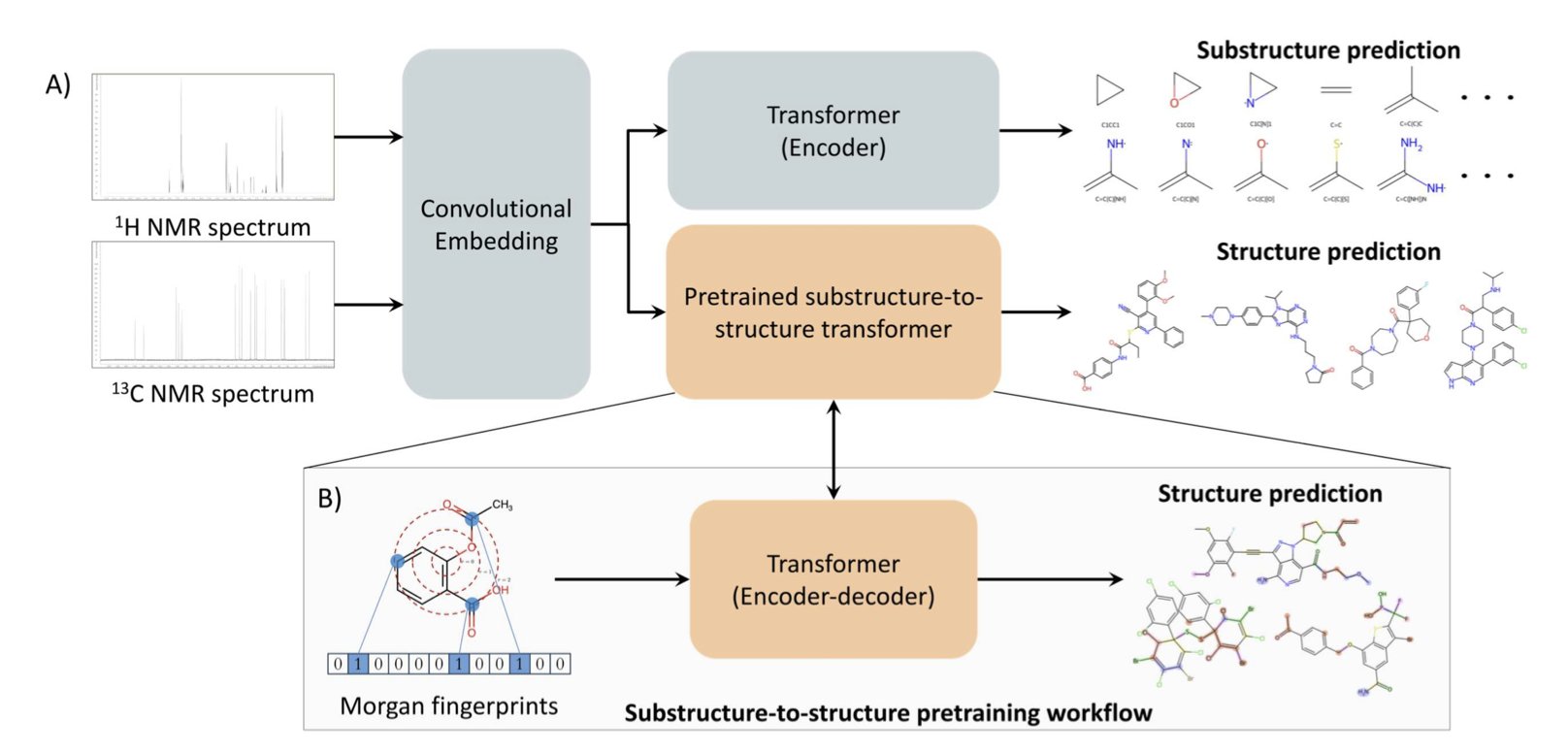

The core concept is to treat structure elucidation as a translation problem. You can think of an NMR spectrum as a “foreign language” and the molecular structure as “English.” The researchers used a Transformer model—the same AI architecture that drives Large Language Models (LLMs)—to act as the “translator.” The input is ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectral data, and the output is the molecule’s SMILES string.

To get the AI to understand chemistry, you first have to teach it chemical “grammar.” The researchers used a clever method: pre-training. Before seeing any spectra, they fed the model a large number of Morgan fingerprints, which are a digital representation of molecules. They tasked the model with reconstructing the full molecular structure from just the fingerprint. The accuracy on this task was 97.8%. This step ensures that the model has a deep understanding of what constitutes a plausible and stable chemical structure before it even starts “learning” spectra.

After training, the model performed well on simulated spectra. For a given spectrum, the probability that the correct answer was among its top 15 candidate structures was 55.2%. This number isn’t 100%, but in practice, this is already a huge help. It’s like being given a high-confidence shortlist. You no longer need to start from scratch; you can focus on verifying a few of the most likely structures.

Of course, the model’s true value depends on its performance on real-world data. Spectra measured in a lab always have various kinds of noise and imperfections. The researchers fine-tuned the model with just 50 real experimental spectra, and the accuracy reached 20%. This shows that the model has good generalization ability. It isn’t just a “theorist” that can only handle clean, simulated data; it has the potential to be used directly in our daily work.

The framework can handle molecules with up to 40 non-hydrogen atoms, a size range that covers the vast majority of small molecules in medicinal chemistry.

One other detail is worth mentioning. The model doesn’t just give a final answer; it also simultaneously predicts substructures within the molecule. This is very similar to how human chemists work: when we see a particular signal in a spectrum, we might instinctively think, “that looks like a phenyl ring” or “that must be a tert-butyl group.” The model’s ability to provide this intermediate analysis makes its “thinking” process more transparent and gives us more clues to verify the results.

📜Title: Pushing the Limits of One-Dimensional NMR Spectroscopy for Automated Structure Elucidation Using Artificial Intelligence 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.18531

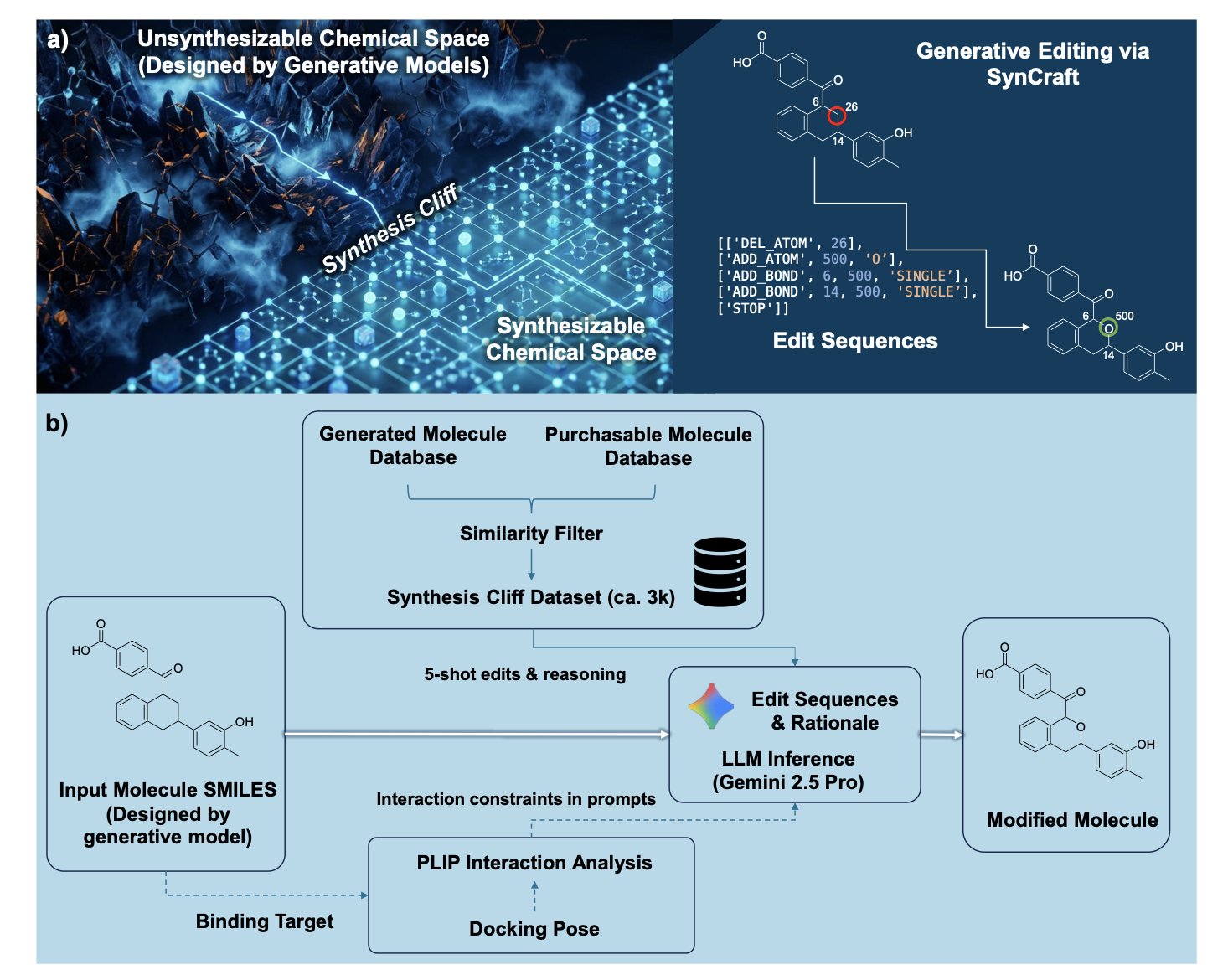

5. AI Molecular Editing: Crossing the Synthesis Cliff

In drug discovery, we’ve all had this headache: the computational team spends ages screening with AI and hands over a molecule with a sky-high predicted activity score. The structure looks great. You take the molecule to a synthetic chemist, who glances at it and says, “We can’t make this. Find another one.”

A molecule like that, no matter how active, is just an illusion. This is a common problem with many AI tools. They excel at creating “ideal” molecules in virtual space but often ignore the constraints of real-world synthesis. A tiny structural difference, like a hard-to-make spirocycle or an unstable functional group, can turn a molecule from “within reach” to “impossible.” This is what the authors call the “synthesis cliff.”

Previous solutions have been blunt. One is to use a synthesis-difficulty filter and just throw out molecules that look hard to make, but this can discard many good candidates. Another is to force the molecule to map onto a known, synthesizable scaffold, but this sacrifices structural novelty and diversity.

Now, SynCraft offers a different approach. It makes a Large Language Model (LLM) mimic how medicinal chemists work: it doesn’t redesign, it edits and modifies.

Here is how it works:

First, SynCraft analyzes a given molecule to identify the “synthetic liabilities” that give chemists a headache.

Second, it doesn’t just generate a new SMILES string. We all know that LLMs can easily make mistakes when handling a strict syntax like SMILES. It’s like asking a poet to write code; one missing parenthesis and the whole program crashes. SynCraft gets around this by generating an executable edit sequence. For example, “replace the tert-butyl group at position 8 with an isopropyl group,” or “break the spirocyclic connection between ring A and ring B.”

This process is implemented using a Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting strategy. It guides the LLM to think like a person: first diagnose the problem, then create a modification plan, and finally execute it. The reasoning process is transparent, so we can clearly see why the AI made a particular change, which is crucial for building trust.

A key point is that it knows how to preserve the “soul” of the molecule. A molecule works because its pharmacophore binds precisely to a protein. If you optimize a synthetic route but get rid of a key hydrogen bond donor in the binding pocket, the optimization is meaningless. SynCraft introduces an “interaction-aware” strategy. It translates 3D protein-ligand interaction information into 2D structural constraints, telling the LLM: “You can’t touch these parts; they are critical for binding.”

In real case studies, like optimizing PLK1 inhibitors and RIPK1 drug candidates, SynCraft performed well. It successfully “rescued” high-scoring hit compounds that had been abandoned due to synthesis challenges, making modifications that were highly consistent with the intuition of experienced medicinal chemists.

Of course, the tool isn’t a silver bullet. Its computational cost is not low, so it’s not suitable for large-scale virtual screening of tens of millions of compounds. Its best use is in the hit optimization stage. When we have a few precious candidates that are active but challenging to synthesize, SynCraft can be a great help, acting like a senior synthetic strategy consultant to provide precise and reliable optimization advice.

📜Title: SynCraft: Guiding Large Language Models to Predict Edit Sequences for Molecular Synthesizability Optimization 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.20333