Table of Contents

- The Dual-LAO method speeds up relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations by 15-30x while maintaining high accuracy, making rapid evaluation of complex molecular edits possible in drug development.

- Arity Map uses simple atomic packing density to quickly distinguish between true disordered regions and simple folding errors in AlphaFold predictions, solving the ambiguity of pLDDT scores.

- Researchers propose a self-knowledge distillation method called LKM, which improves molecular property prediction accuracy by mixing knowledge from different layers of a Graph Neural Network (GNN) at no extra computational cost.

- ReACT-Drug integrates chemical reaction rules into reinforcement learning, enabling an AI to generate molecules that are not only effective but also synthesizable, and it avoids the need to train a new model for each target.

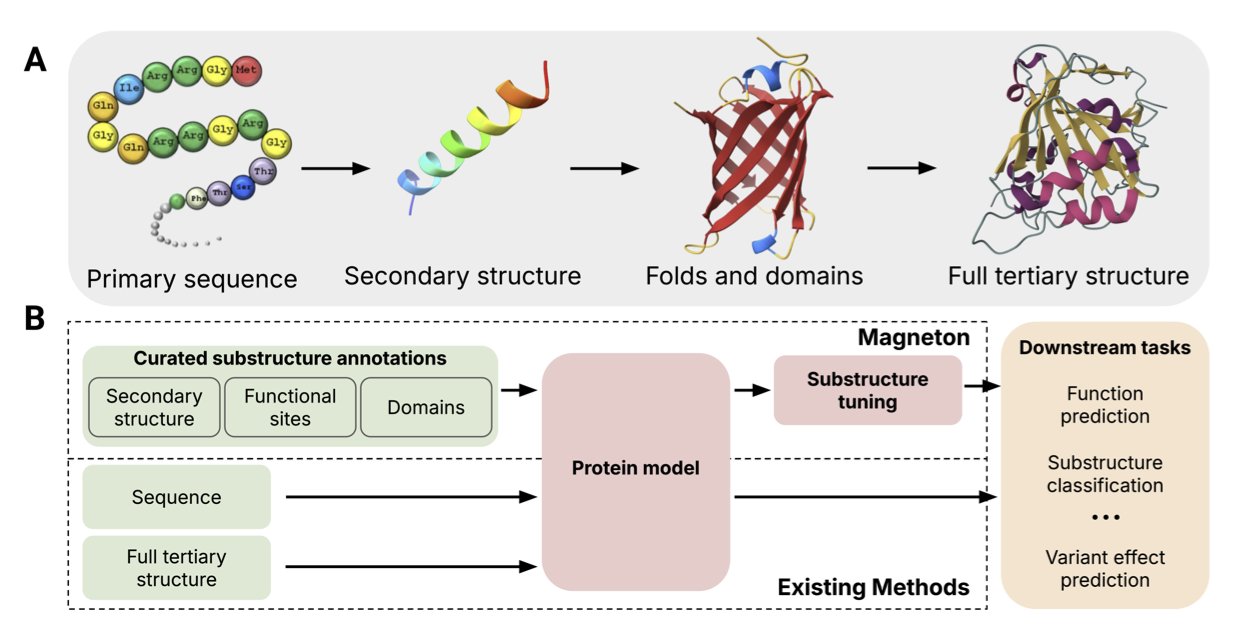

- By explicitly teaching a model to recognize the functional substructures of proteins, researchers achieved a leap in performance for protein language models on function prediction tasks, even outperforming models that rely solely on global structure.

1. Dual-LAO: Up to 30x Faster Relative Binding Free Energy Calculations

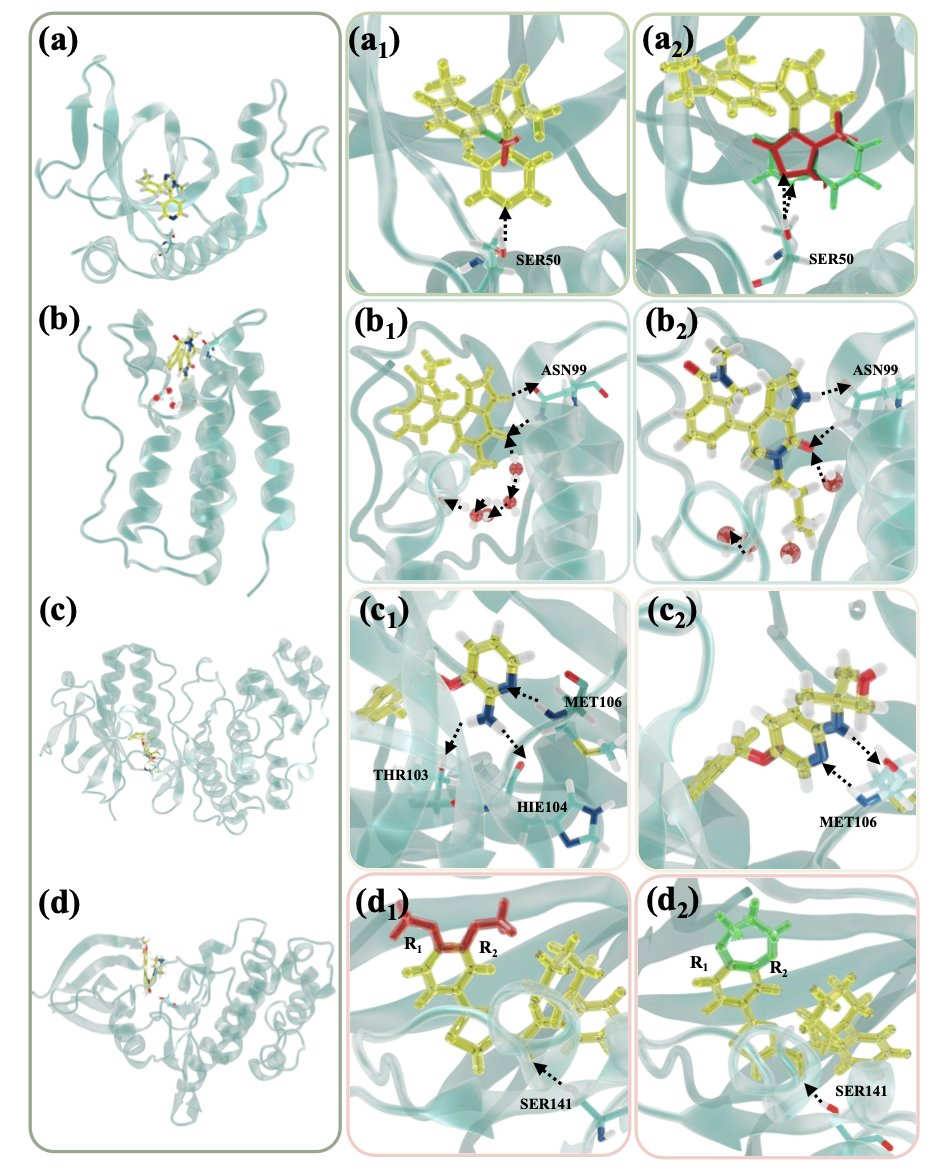

In drug discovery, we’re always playing a high-stakes game of molecular Lego: how can we tweak a known active molecule to make it better with fewer side effects? Computational chemists try to predict the effect of these tweaks using Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE), which is like simulating how tightly a drug will bind to its target inside a computer. The problem is, this process is very slow, especially when the molecular changes are big, like swapping out the entire core structure (scaffold-hopping).

The Dual-LAO method proposed in this work is designed to fix this “slow” problem.

Here’s how it works. Imagine you need to slowly “morph” molecule A into molecule B to calculate their difference in binding energy. In computations, this is called an “alchemical transformation.” In the intermediate states, the molecule is neither A nor B, its structure is weird, and it can easily “drift” out of the target protein’s binding pocket, causing the whole calculation to fail. This is a primary reason why free energy calculations converge slowly and give inaccurate results.

The authors came up with a clever solution. They use a dual-topology setup, which is like putting “ghosts” of both molecule A and molecule B into the simulation at the same time. Then, using a constraint scheme called dual-DBC, they put an invisible “leash” on both molecules. This leash doesn’t lock the molecules in place (which would introduce bias), but gently restrains them to make sure they stay where they should be during the transformation. It’s like guiding a new driver into a parking spot by lightly holding the steering wheel, not grabbing it and parking for them.

The biggest benefit of this method is that it dramatically speeds up free energy convergence. Because the intermediate states are stabilized, the sampling is much more efficient. The authors report a 15 to 30-fold speed increase, which is a huge leap. This means a calculation that used to take weeks might now finish in a day or two.

And it’s not just fast; it’s also accurate. The authors verified this across a series of complex tests, including modifying molecular fragments, replacing buried water molecules, and even handling charge changes. The final root-mean-square error (RMSE) between predicted and experimental values was only 0.51 kcal/mol, which is a very reliable level in this field.

For medicinal and computational chemists on the front lines, this means we can explore chemical space more boldly. Scaffold-hopping ideas that we were hesitant to try can now be quickly evaluated with Dual-LAO. During the lead optimization phase, when faced with dozens or hundreds of modification ideas, this tool can help us quickly filter out the unpromising molecules and focus our resources on synthesizing and testing the ones that truly have potential.

The researchers also integrated this method into the Tinker-HP simulation package and paired it with the advanced AMOEBA polarizable force field. The AMOEBA force field can describe intermolecular interactions more accurately, especially when dealing with changes in charge distribution, which adds another layer of security to the accuracy of the calculations.

Dual-LAO didn’t invent a new theory. Instead, it’s a smart engineering innovation on top of an existing framework that elegantly solves a long-standing pain point in free energy calculations. It makes the powerful tool of RBFE more practical and accessible.

📜Title: Fast, Systematic and Robust Relative Binding Free Energies for Simple and Complex Transformations: Dual-LAO 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.17624v1

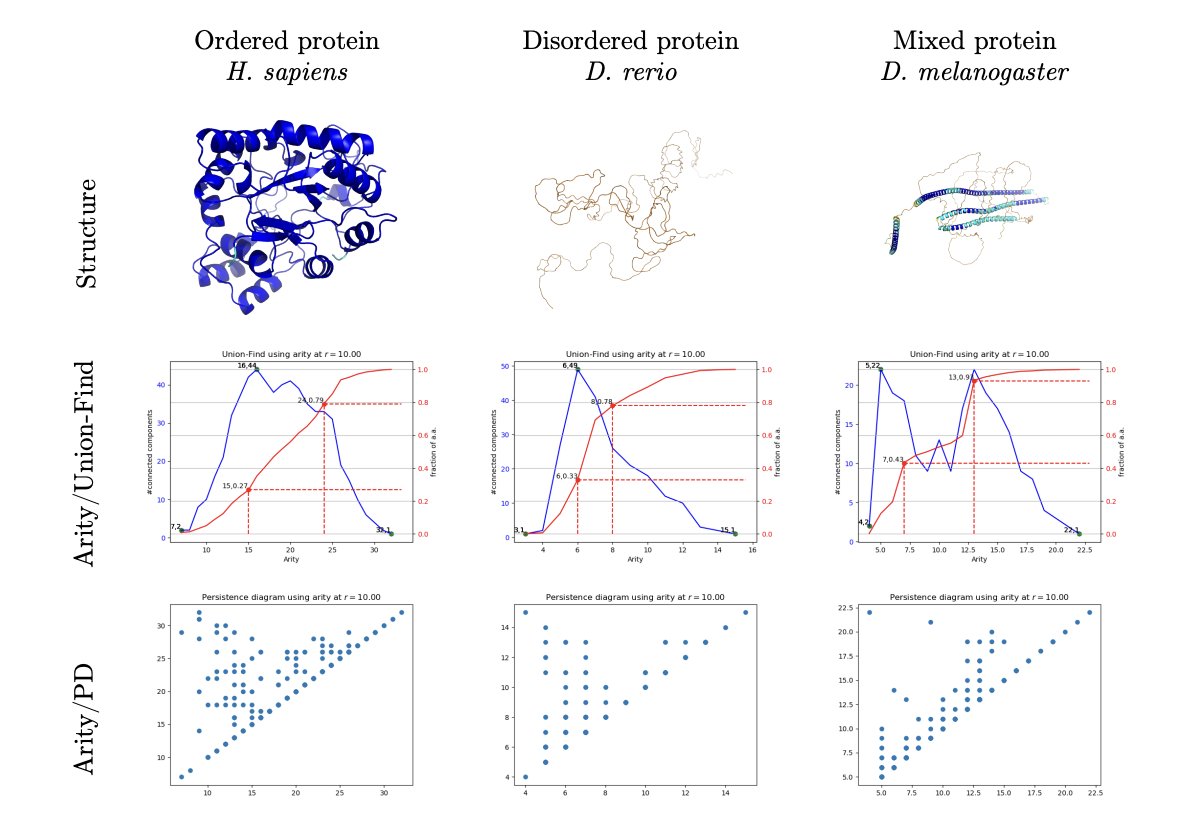

2. Arity Map: Spotting AlphaFold’s Folding Errors at a Glance

AlphaFold changed the game, but we all know its pLDDT confidence score isn’t a silver bullet. When you see a “noodle-like” region with a low pLDDT score, you face a core question: is this part of the protein a naturally flexible, intrinsically disordered region (IDR), or is it a folding error that AlphaFold failed to predict correctly? The answer is critical for drug discovery, because one is a potential binding site, and the other is computational junk that should be thrown out.

The researchers behind this paper came up with a clever way to solve this. They didn’t analyze complex energy functions. Instead, they went back to a very basic physical property: local packing density. In simple terms, it’s about how “crowded” an amino acid residue is. They calculated the number of neighbors within 10 Å of each Cα atom, then took the 25th and 75th percentiles of this distribution to create a 2D plot they call an “Arity Map.”

The map works surprisingly well. All protein structures are clearly separated into two regions: 1. Native Sector: Structures here are tightly and regularly packed. The researchers validated this using experimental structures from the PDB database and found that almost all of them fall in this region. This is like calibrating the map with known landmarks. 2. Heterogeneous Sector: Structures here are loosely and unevenly packed. All the low-pLDDT regions land here, but the key is that this sector is a mixed bag.

Through further analysis, the researchers discovered that a large portion of AlphaFold’s predicted “disordered regions” are actually folding errors. For example, some domains that should be compact are incorrectly stretched into coils, or they form biologically implausible conformations, like a bent alpha-helix. On the Arity Map, these structures occupy different positions than truly disordered proteins (from the DisProt database). This suggests that AlphaFold is a bit like an overly cautious student; when it encounters uncertainty, it tends to give the safe but vague answer of “disordered.”

What’s more, existing structure quality assessment tools, like PROCHECK or VoroMQA, almost completely miss these errors. They either think everything is fine or attribute the problem to “poor packing,” without offering deeper insight.

To make this more practical, the researchers used 22 features from the Arity Map to train a new single-residue scoring system called “abstraqt.” This score is more discerning than pLDDT; it’s specifically designed to identify structures that look strange but don’t violate basic chemical principles. For example, an alpha-helix that should be straight but has an unnatural bend in the middle might look fine to pLDDT, but abstraqt can flag it.

For people in drug development, this means we now have a fast, reliable tool to “quality check” AlphaFold predictions for entire proteomes in minutes. Before running large-scale virtual screens or designing structures, we can use the Arity Map to filter out suspicious, “false positive” disordered regions and focus our computational resources on structures that are actually valuable.

📜Title: Fold or Flop: Quality Assessment of AlphaFold Predictions on Whole Proteomes 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.19.695427v1 💻Code: https://sbl.inria.fr/applications/alphafold_analysis.html

3. A New Trick for GNNs: Better Molecular Property Predictions at Zero Cost

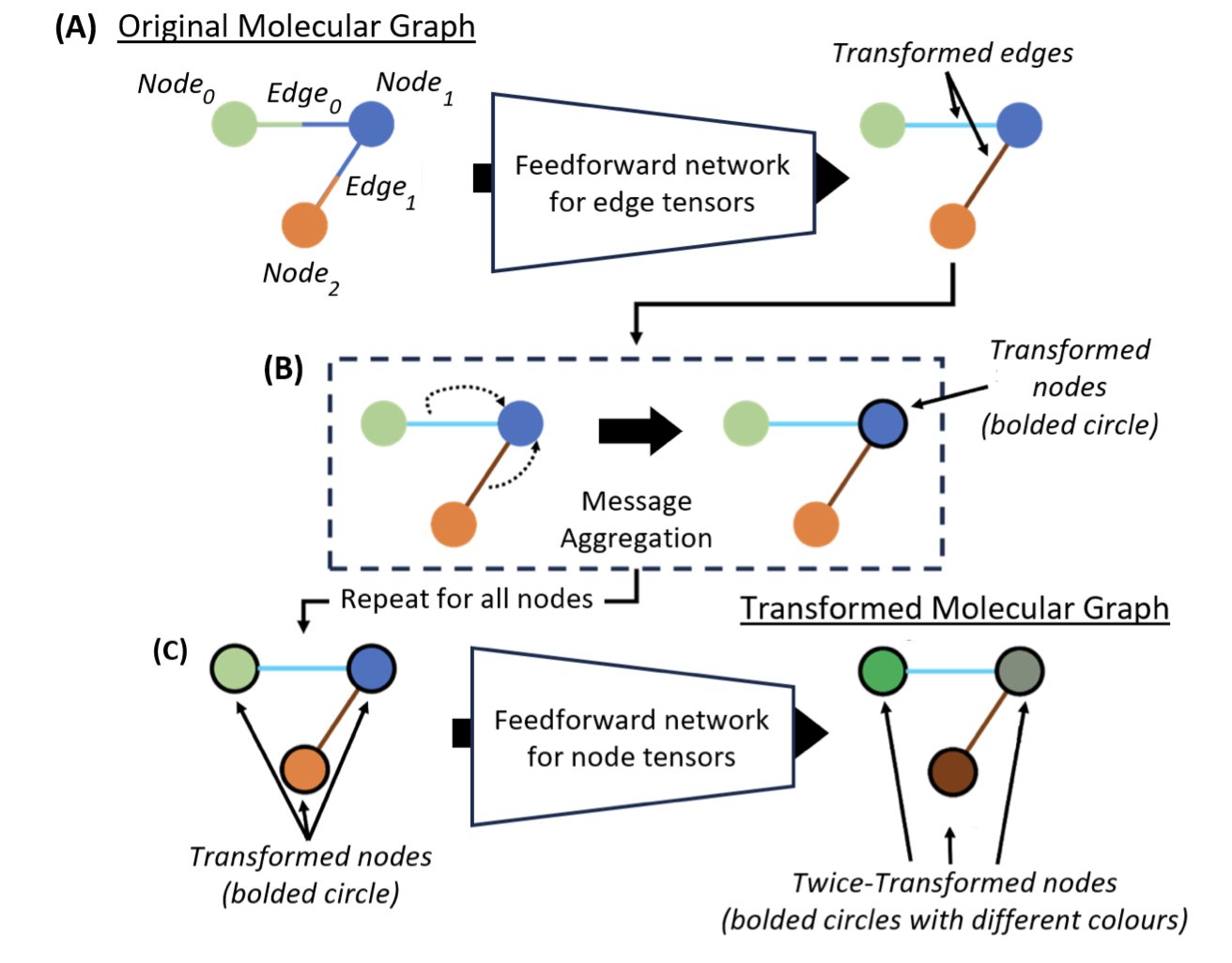

In computational chemistry and drug discovery, we work with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) all the time. They are great at understanding molecular structures, but everyone is always thinking about how to make them more accurate without making the models bigger and slower. A recent paper introducing Layer-to-Layer Knowledge Mixing (LKM) offers a pretty good answer.

First, let’s review how a GNN “sees” a molecule. You can think of each layer of a GNN as a lens with a different focal length. The first layer sees an atom’s immediate neighbors—the atoms it’s bonded to. The second layer can see the “neighbors of neighbors,” expanding its field of view. The more layers, the more complete its view of the global molecular information.

In the past, these “lenses” worked independently, with information flowing in one direction from shallow to deep layers. The authors of this paper thought, why not let these observers at different scales “talk” to each other?

This is the core idea of LKM. It treats each layer as an independent “expert”: shallow layers are “local detail experts,” and deep layers are “global structure experts.” LKM makes these experts learn from and “calibrate” each other during training.

How does it work? The method is very direct. During training, LKM adds a constraint that requires the hidden embeddings from different layers—their internal representations of the molecule—to be as close to each other as possible. It’s like forcing an analyst who only looks at details to understand the global strategy, while also requiring the strategist not to ignore the specific situation on the ground. This way, each layer is forced to absorb information from the other layers. The final molecular representation contains both precise local chemical environments and the overall topological structure.

This process is called “self-knowledge distillation” because the model uses one part of itself (the deep layers) to “teach” another part (the shallow layers), and vice versa, without needing an external, more powerful “teacher model.”

How well does it work? The data speaks for itself. The researchers tested LKM on several mainstream GNN architectures (like DimeNet++ and MXMNet). On the QM9 dataset, prediction error was reduced by nearly 10%. On the MD17 energy prediction task, the error was reduced by 45.3%. These are standard datasets in our field, and achieving such improvements is quite a feat.

The most attractive part for me is that LKM is a “zero-cost” improvement. It doesn’t add any new model parameters, and the computational overhead is negligible. This means we can use it like a plugin on our existing GNN models and get an immediate performance boost. In industrial R&D settings where we handle large compound libraries, this kind of “free lunch” is extremely valuable because it directly impacts screening efficiency and cost.

Overall, LKM provides a simple, effective, and universal strategy to enhance the power of GNNs. It’s not one of those complex techniques that requires huge computational resources to reproduce; it’s a practical trick we can start trying in our own projects right away.

📜Title: Layer-to-Layer Knowledge Mixing in Graph Neural Network for Chemical Property Prediction 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.20236

4. ReACT-Drug: Teaching AI to Design Synthesizable Drugs with Reaction Templates

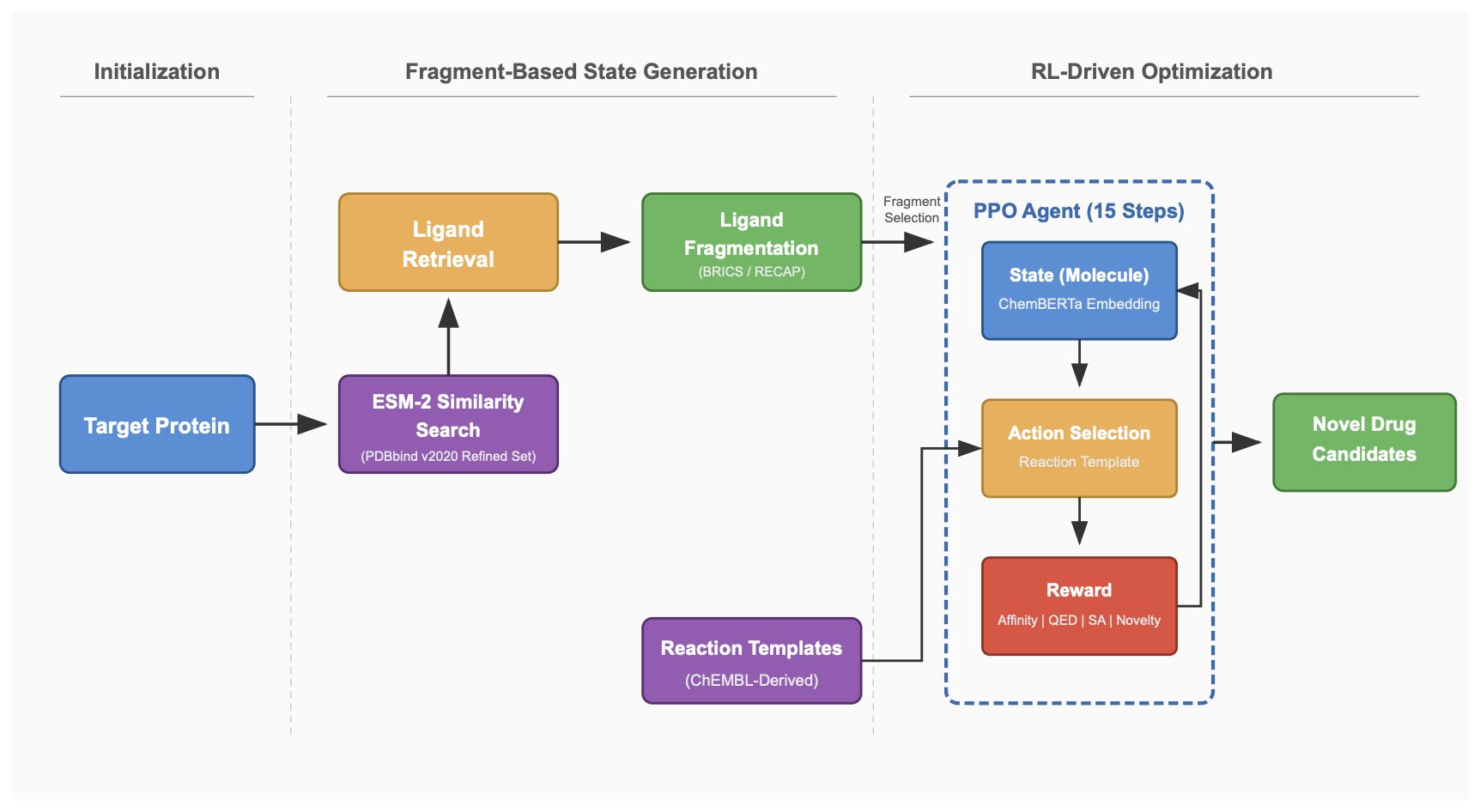

Anyone in computer-aided drug design (CADD) has had a similar experience: an AI model proposes a molecule with a super high predicted binding affinity, a top score, and a novel structure. But when you show it to a synthetic chemist, they tell you, “You can’t actually make this thing in the real world.” This problem has long plagued the AI drug discovery field—how to make an AI design molecules that are not just “good-looking” but also “doable.”

The ReACT-Drug framework proposed in this paper offers a very clever solution. Its core idea is not to let the AI piece together atoms however it wants, but to give it a “chemist’s toolbox” of well-validated chemical reaction templates.

Here’s how it works:

The first step of the process is to solve the cold-start problem for new targets. When you have a new target with little to no activity data, traditional models often struggle. ReACT-Drug’s approach is to first use ESM-2 (a powerful protein large language model) to compute an embedding for the target protein. You can think of this as generating a unique “fingerprint” for each protein. Then, the model searches a massive database for proteins with the most similar fingerprints.

After finding these “relative” proteins, the model looks at the known ligands that bind to them. These ligands are broken down into a series of chemical fragments, which form an initial “building block” pool. This is a smart approach because it’s based on a reasonable assumption: proteins with similar structures are likely to have similar binding pockets, so a fragment that binds to one might also be useful in the pocket of another.

Next, a Reinforcement Learning agent enters the scene. It picks a fragment from the “building block” pool as a starting point and begins a “molecule growing” game. The key is that the agent’s action at each step isn’t simply to add an atom or a functional group. Instead, it selects and executes a real chemical reaction from a predefined “reaction template library.” For instance, it might choose to perform a Suzuki coupling to connect two fragments or use an amidation to introduce an amide bond.

Every time the agent builds a new molecule, its binding affinity with the target is calculated via molecular docking. This affinity score is the “reward” for the agent. Through thousands and thousands of trials, the agent gradually learns how to combine these chemical reactions to consistently generate molecules that bind tightly to the target.

So what’s the value of this framework?

First, it greatly increases the synthesizability of the generated molecules. Since the entire construction process is a simulation of a series of real chemical reactions, the final product is, in theory, synthesizable via a corresponding route. The paper reports that the chemical validity and novelty of its generated molecules reached 100%, which is quite good for a generative model.

Second, its “target-agnostic” nature makes it very flexible. For new targets that are under-researched and have sparse data, this method can still get started quickly and produce reliable candidate molecules. The researchers tested ReACT-Drug on 6 different types of targets, including 5-HT receptors, opioid receptors, and several kinases. The results showed that the binding affinity scores of the generated molecules ranged from -9.13 to -10.4 kcal/mol. What does this mean? It’s on par with a very good hit compound, providing an excellent starting point for subsequent medicinal chemistry optimization.

Of course, the success of this framework is also highly dependent on the quality and breadth of the “reaction template library.” If the library’s reactions are too few or too niche, the chemical space the AI can explore will be limited. But as an automated design platform that integrates a protein language model, reinforcement learning, and synthetic chemistry rules, ReACT-Drug has certainly taken another step forward in bringing AI drug discovery closer to practical application.

📜Title: ReACT-Drug: Reaction-Template Guided Reinforcement Learning for de novo Drug Design 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.20958v1 💻Code: https://github.com/YadunandanRaman/ReACT-Drug

5. Teaching AI to Recognize Protein “Lego Blocks” Leads to a Jump in Function Prediction

In computer-aided drug discovery, we deal with all sorts of protein models every day. Models like ESM are powerful and can extract a lot of information from an amino acid sequence. But sometimes they’re like a student new to a foreign language—they can get the general meaning of a sentence but miss the keywords and idioms. Protein is also a language, and the “keywords” and “idioms” that actually perform functions are the substructures that biologists have studied for decades, like domains and motifs.

A protein isn’t just a uniform chain of amino acids. It’s more like something built from “Lego blocks” with different functions. Some blocks are responsible for binding ATP, others for catalyzing reactions. For a long time, we’ve had a question: do today’s AI models really understand these “Lego blocks”? Or are they just learning fuzzy correlations from massive amounts of data through brute force?

This new work gives us an answer. The researchers built an environment called Magneton. What does it do?

First, they compiled a huge database of 530,000 proteins with 1.7 million known substructure annotations. This is like giving the AI a very thick “dictionary” where every word (substructure) has a detailed definition (function).

Then, they proposed a simple and direct training method called “substructure-tuning.” How does it work? You take a pre-trained protein model (like ESM) and re-educate it using this “dictionary.” Through supervised learning, you force the model to pay attention to and understand these specific functional substructures. It’s like telling a student, “Don’t just read the whole text. Circle these high-frequency words and phrases, and remember what they mean.”

The effect was immediate. For Enzyme Commission (EC) classification, a standard ESM model has an Fmax score of 0.688. After substructure-tuning, that number jumped to 0.815. For Gene Ontology (GO) prediction, it also improved from 0.429 to 0.525. This isn’t just an optimization in the third decimal place; it’s a real leap in performance.

One of the most interesting points is that the researchers tested the relationship between substructure information and global 3D structural information. Many people might think that if you have the precise 3D structure of a protein (like from AlphaFold), the model should be able to figure everything out on its own. But the experimental results show that’s not the case. Even models that had already incorporated global structural information saw further performance gains after substructure-tuning.

What does this tell us? Substructure information is a unique, complementary signal. For example, the global structure tells you the overall look and shape of a building, while the substructure information tells you which room is the kitchen, which is the bedroom, and exactly where the stove and sink are in the kitchen. Both are critical for understanding the “function” of the building; you can’t do without either.

Even better, the model trained this way showed an ability to generalize. When researchers tested it on substructures the model had never seen during training, it still produced very consistent and accurate representations. This means the model isn’t just memorizing a “question bank”; it has actually learned the underlying rules of functional units. It’s starting to understand what combinations and spatial arrangements of amino acids form a “part” with a specific function.

The greatest value of this work is that it takes decades of knowledge about protein function, painstakingly accumulated by biologists, and “injects” it into modern AI models in an efficient way. They’ve also open-sourced the entire environment, dataset, and models for anyone to use. For researchers on the front lines, this means we can train models that have a deeper understanding of biology to do more accurate target function annotation, design better enzymes, or find potential sites of drug action. This is a beautiful piece of engineering and a tribute to classical bioinformatics knowledge.

📜Title: Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts: Building Substructure into Protein Encoding Models 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.18114 💻Code: Not provided