Table of Contents

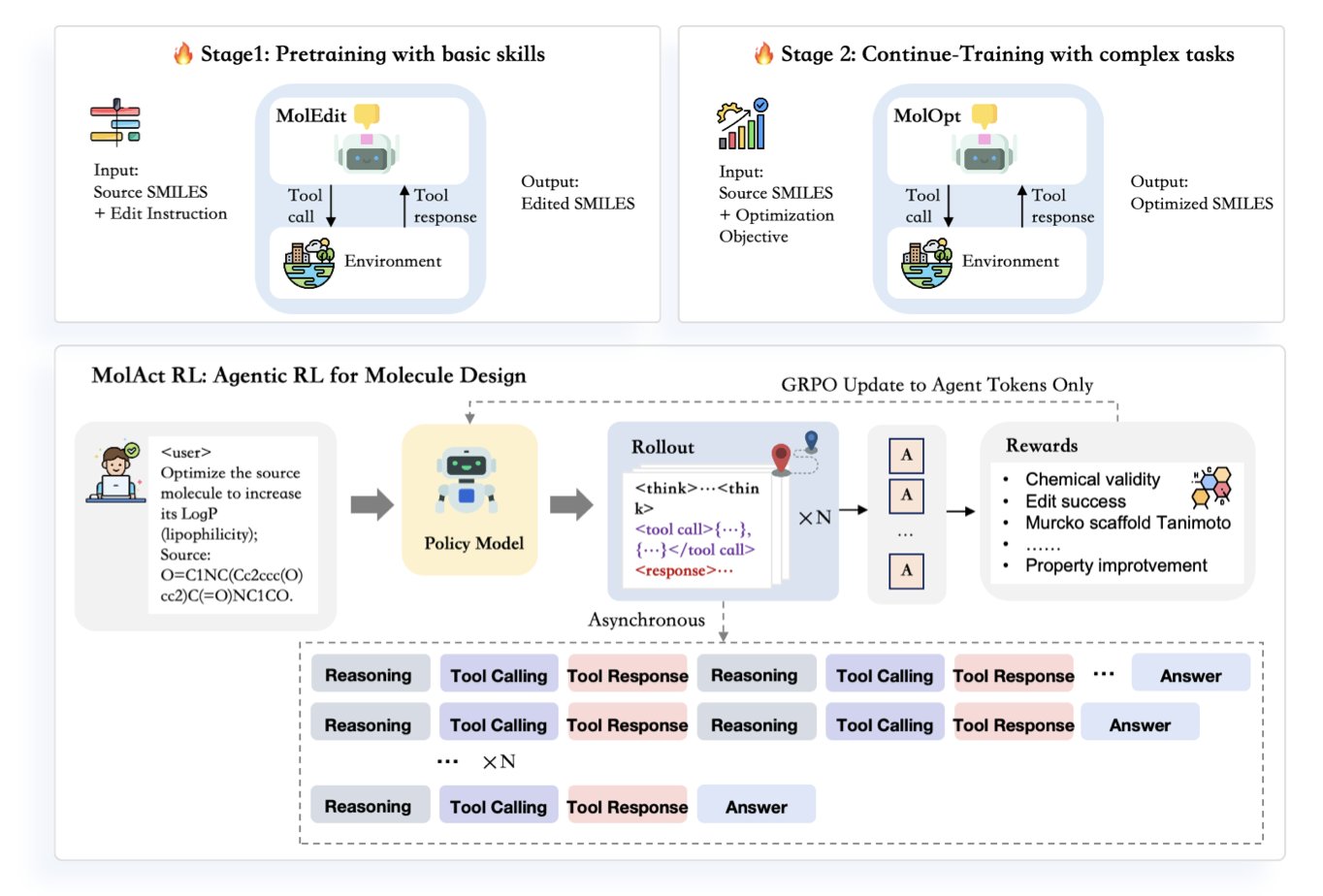

- The MolAct framework enables large models to act as an “intelligent agent” that uses tools. Through two-stage reinforcement learning, it first learns fundamentals and then optimizes, proving that in molecular design, a model must not only “know” chemistry but also “do” it.

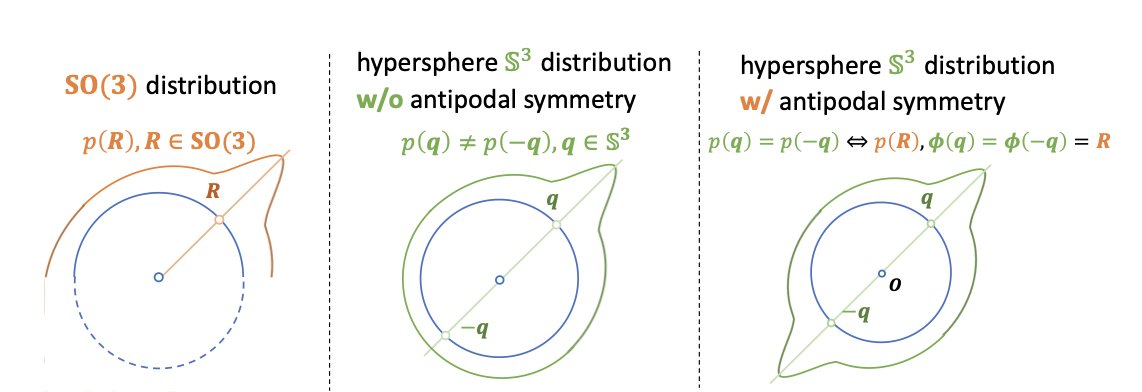

- The ProBayes model uses a unified Bayesian flow framework to simultaneously design a protein’s backbone, sequence, and side chains. This solves the information shortcut problem and improves the accuracy and efficiency of all-atom protein design.

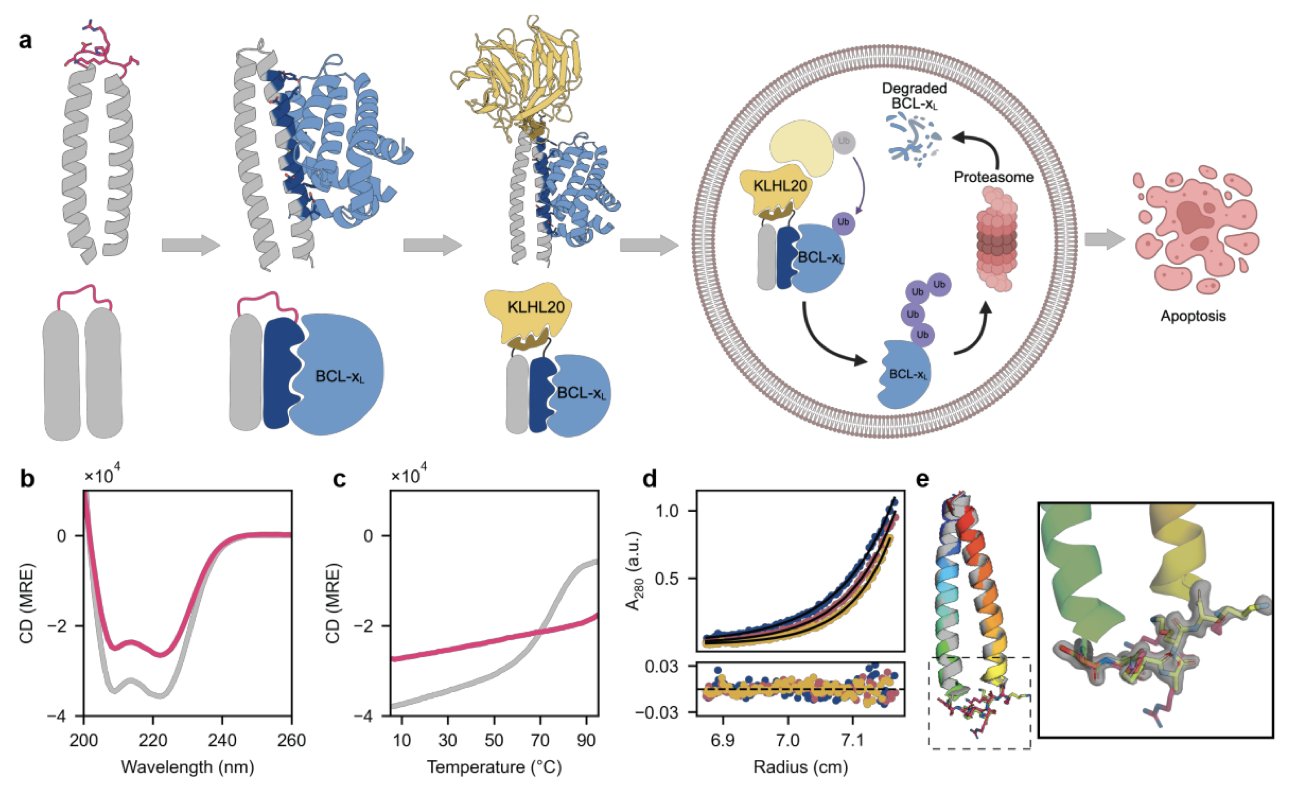

- De novo designed bifunctional proteins can serve as effective targeted protein degraders, offering a new modular platform that goes beyond small-molecule PROTACs.

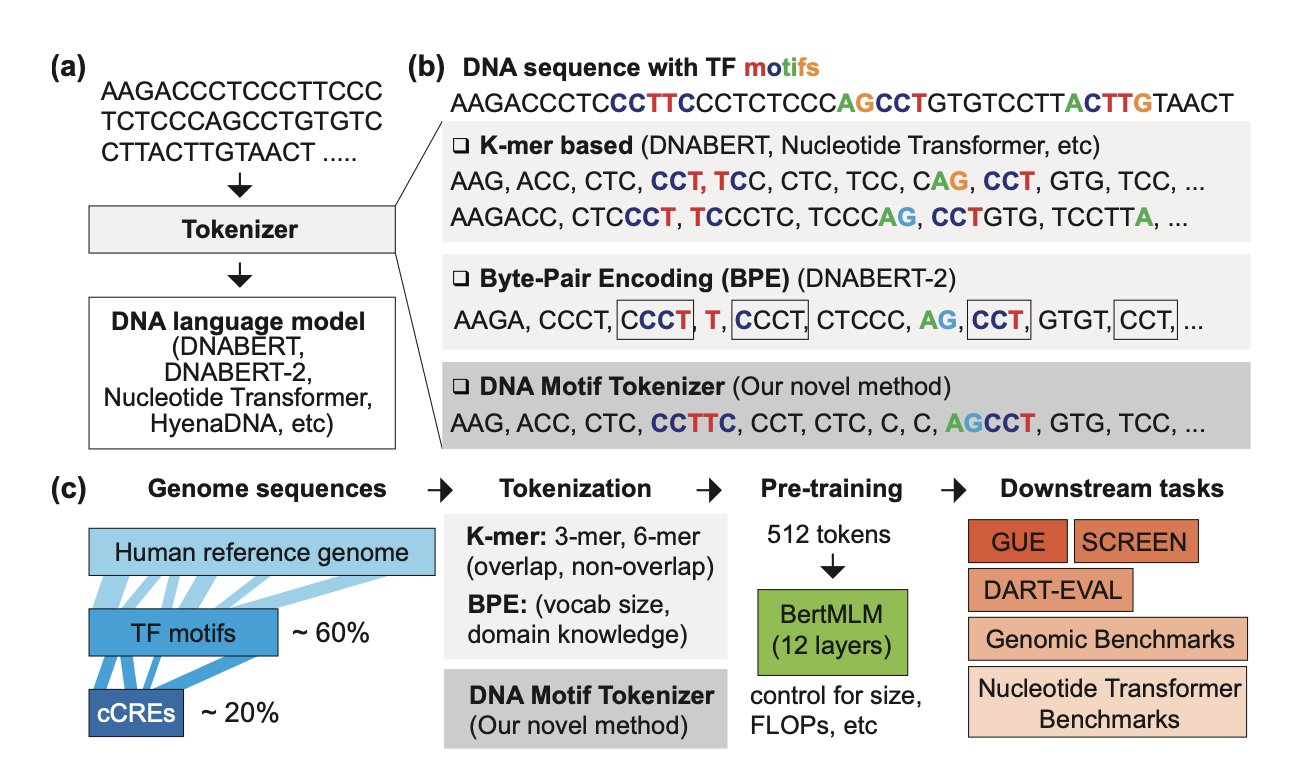

- By directly integrating known DNA functional motifs into the vocabulary, researchers developed a new tokenizer that allows genomic language models to understand DNA sequences more accurately and interpretably.

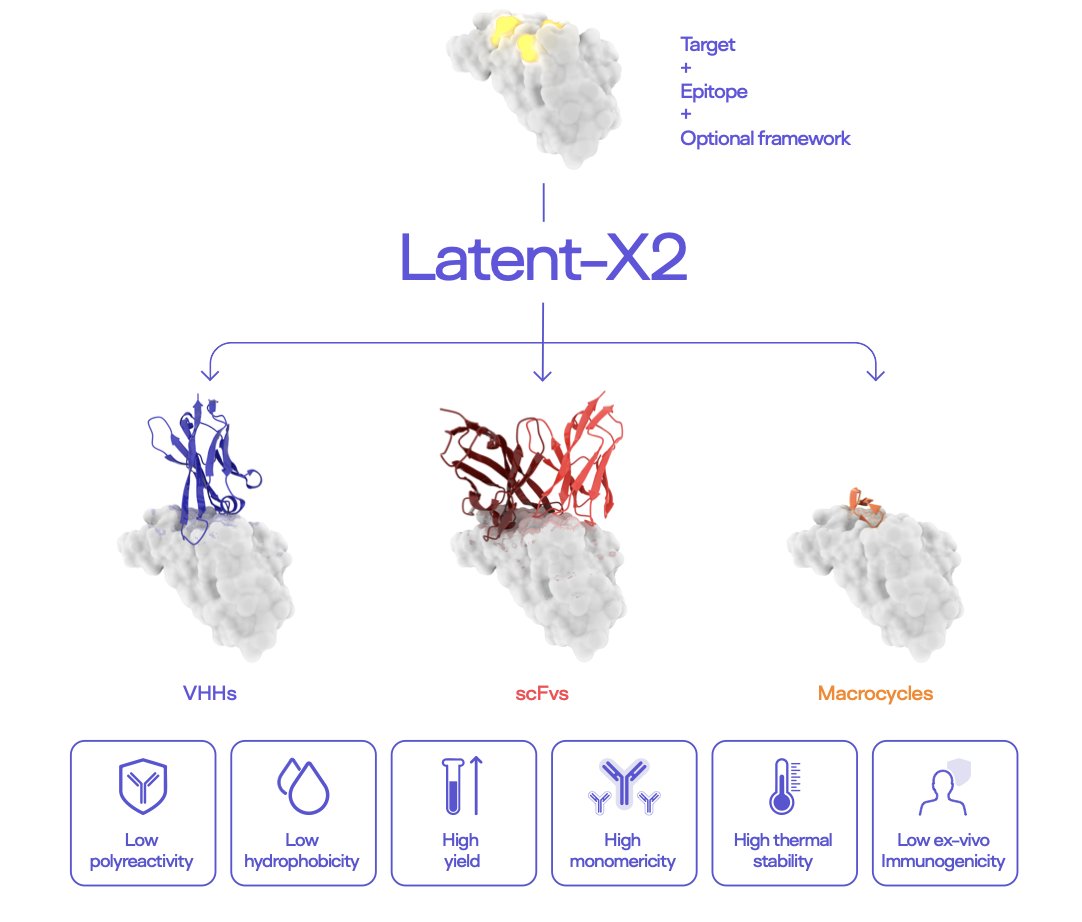

- The Latent-X2 model can generate antibodies with high affinity, low immunogenicity, and good developability in a single step, eliminating the need for later optimization and solving a key bottleneck in AI drug discovery.

1. MolAct: Getting AI to Think and Edit Molecules Like a Chemist

In drug discovery, the daily work is basically molecular editing. We get a lead compound and try to add a group here or swap an atom there to see if we can boost activity or improve ADME properties. The process is full of trial and error, reasoning, and relying on experience. A new paper proposes a framework called MolAct that tries to get AI to do this in a way that’s very similar to how chemists work.

The core of this method is to turn the AI into an “agent.” You can think of it as a virtual chemist sitting at a computer. It doesn’t just generate a new molecule out of thin air. Instead, it modifies an existing molecule step by step, just like we do.

Here’s how it works, in two stages.

The first stage is “schooling.” In this phase, the AI’s task is to learn the most basic chemical operations: adding an atom to a molecule, deleting a functional group, or swapping one group for another. It doesn’t pursue any optimization goal at this point; it just needs to make sure its edits are chemically “legal.” This is like when we first learn organic chemistry and have to master basic reactions, knowing what can and can’t be done.

The second stage is “project work.” After the AI “graduates,” it gets a specific optimization task, like increasing a molecule’s LogP (logarithm of the partition coefficient). It looks at the starting molecule and starts thinking: “To raise LogP, I need to make the molecule more hydrophobic. Maybe I can add a methyl group to this benzene ring?” Then, it executes the “add methyl” action.

The next step is key: it uses external “tools” to evaluate the result. These tools could be cheminformatics software to check if the modified molecule is still valid, or a prediction model to calculate the new LogP value. After getting feedback—“Great, LogP did increase”—it plans its next edit based on this new molecule. The whole process is a “think-act-feedback” loop that continues until the goal is met or it runs out of steps.

This approach of integrating external tools makes the entire process very close to real-world R&D. We chemists do the same thing: we get an idea, draw the structure in a program, and then run prediction tools to see how it looks. MolAct automates this workflow.

So, how well does it work? The researchers found that the size of the model is critical. They trained a 7B parameter model (MolOptAgent-7B) and a smaller 3B model. The 7B model performed significantly better on multi-step optimization tasks.

There’s an interesting observation here: the smaller 3B model actually knew what kind of molecule was better (its reward model fit well), but it just couldn’t effectively plan a series of actions to get to that good result. It often got stuck in the middle steps or ran out of interaction attempts quickly. This perfectly illustrates the gap between “knowing” and “doing.” It’s like a junior chemist who has memorized a lot of theory but has no idea how to design a synthetic route. The 7B model, on the other hand, is more like a senior chemist who not only has the knowledge but can also formulate and execute a multi-step plan.

Of course, this framework has its limits. First, it heavily depends on the accuracy of the external tools. If your property prediction model is inaccurate, the AI agent will be misled. It’s a case of “garbage in, garbage out.” Second, it currently doesn’t consider synthetic accessibility. A molecule that looks perfect on a computer is useless if you can’t make it in the lab.

Still, the “agent” paradigm proposed by MolAct is an important step forward. It makes the AI’s process more like a transparent, interpretable chemical reasoning process, rather than a mysterious “black box” generation. This not only makes the results more reliable but also makes it easier for us to understand and control the AI’s design strategy.

📜Title: MolAct: An Agentic RL Framework for Molecular Editing and Property Optimization

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.20135v1

2. ProBayes: Nailing All-Atom Protein Design with Bayesian Flow

Designing proteins is like playing with three different kinds of Legos at the same time: first you have to build the backbone, then decide which color and shape of bricks to use (sequence), and finally, you have to place some special small parts (side-chains) in precise locations. All three are interconnected and essential. Many past computational models handled this problem in separate steps or took “shortcuts” in processing information. For instance, a model might get lazy and “guess” the sequence directly from the side-chain’s structural information, instead of truly learning to design the sequence from the backbone. This is like a student learning by copying answers instead of solving the problems. The result is predictable.

The ProBayes model, introduced in this study, was created to solve this fundamental problem. The researchers built a unified generative framework where the design of the backbone, sequence, and side chains happens in one seamless process. They used a technique called “Bayesian flow,” which you can think of as a sophisticated piping system. In this system, the direction and order of information flow are strictly controlled. The model must first generate the sequence based on the backbone information, and then generate the side chains based on both the backbone and sequence information. This closes off any possibility of taking shortcuts, forcing the model to learn the truly complex relationship between protein structure and sequence.

One clever part is how they handle the challenge of protein backbone orientation. The placement of a protein backbone isn’t random; its rotation angle is crucial. Building a generative model directly in the 3D rotation space (known academically as the SO(3) group) is very complex. The researchers found a way to convert this complex rotation problem into a problem of finding symmetric points on a high-dimensional sphere. This transformation is like turning a tricky 3D geometry problem into a relatively simple 2D geometry problem, making the calculation more direct and stable.

So how did it perform? On PepBench, a well-recognized testing platform for peptide design, ProBayes achieved a DockQ score of 0.74, a top-tier result among existing methods. In more complex antibody design tasks, it generated protein structures with lower energy and achieved higher sequence recovery rates, both of which are key metrics for evaluating design quality.

This work is significant for drug development. Whether we’re developing new antibody drugs or designing enzymes with specific functions, we need to control every single atom of the protein with precision. ProBayes provides a more efficient and accurate tool, bringing us one step closer to the goal of “custom-designing” functional proteins.

📜Title: Rationalized All-Atom Protein Design with Unified Multi-Modal Bayesian Flow

🌐Paper: https://openreview.net/pdf/5427b0c4461e72ab1d2de811fb8dc817639a8e83.pdf

💻Code: https://github.com/GenSI-THUAIR/ProBayes

3. Protein Legos: Designing Protein Degraders from Scratch to Challenge PROTACs

In the field of Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD), we’re most familiar with small molecules like PROTACs. The principle is simple: it acts like a molecular “handcuff,” grabbing the target protein with one end and an E3 ubiquitin ligase with the other. This brings them together, causing the cell’s own waste disposal system (the proteasome) to get rid of the target protein.

This strategy has been very successful, but anyone who has worked on it knows how difficult it is to design a good PROTAC molecule. You need a molecule that can bind your target with high affinity and also grab a suitable E3 ligase, like VHL or CRBN. Both tasks are hard on their own. Squeezing them into a single molecule while maintaining good drug-like properties is a huge challenge. And we only have a handful of E3 ligases we can use, so the options are limited.

Mylemans and his colleagues took a different approach: if small molecules are so hard to make, why not use proteins to do the job? Proteins are nature’s experts at carrying out complex biological functions.

Their idea was to design a completely new protein from scratch (de novo) to act as the “handcuff.”

First, they needed a stable and reliable “scaffold.” They designed a helix-turn-helix structure. You can think of it as a very stable Lego base that is structurally rigid and won’t fall apart inside a cell. This base was built on a type of peptide called a coiled-coil, which they optimized to be highly thermostable, ensuring it could function properly in the 37°C environment of a cell.

With the base in place, the next step was to “snap on” the functional modules. They needed two functions: one to grab the target protein, and another to grab an E3 ligase.

The researchers chose the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-xL as their target, a classic cancer target. They integrated a high-affinity binding fragment of BCL-xL onto one end of the protein scaffold.

For the other end, they didn’t go for the common VHL or CRBN. Instead, they targeted the E3 ligase KLHL20. KLHL20 typically binds its substrates by recognizing a specific short linear motif (SLiM). This was a smart choice, because designing a short peptide that KLHL20 can recognize is far more direct than designing a complex small molecule to bind VHL. So, they attached this SLiM sequence to the other end of the protein scaffold.

The entire design process relied heavily on computational tools. They used powerful software like ProteinMPNN and AlphaFold2 to design the sequence and predict the folded structure, making sure this new bifunctional protein would form the intended 3D shape correctly.

The final product was a custom-made protein: a stable scaffold with one end that can grab BCL-xL and another that can recruit KLHL20.

The design looked good on paper, but the real question was whether it would work in the real world. The researchers tested it in vitro and in cell experiments. The results were excellent. This protein degrader effectively pulled BCL-xL and KLHL20 together, leading to the ubiquitination and eventual degradation of BCL-xL. In lung cancer cells, it successfully induced apoptosis.

A crucial comparison showed that its effectiveness was on par with the well-known small-molecule PROTAC, DT2216, which also targets BCL-xL for degradation. This result proves that protein degraders are not only conceptually viable but can also compete with small-molecule drugs in terms of potency.

The value of this work lies in its “platform” approach. The protein scaffold is modular. In theory, we could target any protein of interest by swapping in different binding domains. We could also swap the SLiM sequence to recruit any of the hundreds of E3 ligases in the cell. This greatly expands the potential applications of TPD and offers new solutions for “undruggable” targets.

📜Title: De novo designed bifunctional proteins for targeted protein degradation

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.22.695915v1

4. DNAMotifTokenizer: A Gene Tokenizer That Speaks Biology

When we train large language models, the first step is always “tokenization.” This means breaking up a sentence, like “I am a scientist,” into basic units the model can understand, such as ["I", "am", "a", "scientist"]. This process is critical for the model’s performance.

So, how should we tokenize a genomic sequence—that string of A, C, G, and T that makes up the code of life?

The simplest and most direct method is k-mers. This just chops the DNA sequence into fixed-length (k) fragments. For example, with k=3, ATTCGATT becomes ATT, TTC, TCG, CGA, GAT, ATT. The problem with this method is obvious: it completely ignores biological functional units. It’s like mechanically chopping the word “unforgettable” into “unf,” “org,” “ett,” “abl,” and “e.”

Later, people started using Byte Pair Encoding (BPE). This is an algorithm that learns the most frequent combinations from the data. It might learn a frequently occurring sequence like GATTACA as a single token. This is a step up from k-mers, but it’s still a “statistician,” not a “biologist.” It doesn’t know that GATTACA might happen to be an important transcription factor binding site, or that GAT and TACA lose their biological meaning when split apart.

The new work proposing DNAMotifTokenizer aims to solve this problem.

Its core idea is: why don’t we just tell the model which DNA fragments are important?

In biology, we already know of thousands of short DNA sequences with specific functions, which we call “motifs.” The most typical examples are the binding sites for Transcription Factors (TFs). These sites act like “switches” or “signposts” in the gene regulatory network.

Here’s how DNAMotifTokenizer works:

1. Build an expert dictionary: Instead of learning from scratch, it starts by directly loading a database of known transcription factor motifs (like JASPAR) into its initial vocabulary. These motifs become its “core words.”

2. Greedy matching: When it gets a new DNA sequence, it uses a greedy algorithm to tokenize it. The algorithm prioritizes finding and matching the longest known biological motifs from its vocabulary within the sequence. This is like a linguist who knows Latin roots reading a text. They would instantly recognize “bio-” and “-logy” instead of splitting “biology” into “biol” and “ogy.”

The benefits of this approach are clear. The tokenization results are no longer statistical accidents but are built on a solid biological foundation. From the very beginning, the model is exposed to meaningful biological “words” instead of random combinations of letters.

To prove the superiority of this method, the researchers conducted a series of rigorous benchmarks. They also built a comprehensive benchmark dataset called SCREEN, which covers a variety of regulatory tasks in human functional genomics.

The results showed that, under the same pre-training conditions, models using DNAMotifTokenizer outperformed models using a BPE tokenizer on almost all downstream tasks. An even more interesting finding was that even for BPE, training the tokenizer on a smaller but more biologically meaningful dataset (like sequences from promoter regions only) led to better performance than training it on the entire genome.

This reinforces the idea that for specialized AI applications, high-quality data with domain knowledge is far more valuable than massive amounts of generic data.

What does this mean for drug discovery? A model that can understand the language of gene regulation more deeply can help us more accurately predict the functional impact of non-coding mutations, find new drug targets, or better understand the mechanisms of existing drugs. The model’s interpretability is also greatly enhanced. When we see the model assign a high weight to a particular TF motif, we can immediately connect it to a known biological pathway, instead of scratching our heads over a bunch of meaningless k-mer sequences.

📜Title: Dnamotiftokenizer: Towards Biologically Informed Tokenization of Genomic Sequences

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.17126

5. AI Designs Drug-like Antibodies in a Single Step, Solving Immunogenicity

Anyone in antibody drug discovery knows that finding a molecule that binds to a target is just the first step. The real challenge comes from the series of optimizations that follow: improving affinity, reducing immunogenicity, and solving problems with manufacturing and stability. This process is long, expensive, and full of uncertainty. Any step can lead to failure.

The Latent-X2 model in this paper looks like it wants to do all these steps in one go.

From “Needle in a Haystack” to “Following a Blueprint”

Traditional antibody screening methods, like phage display, use libraries that can have over a trillion candidates. The amount of work required to screen a library that large is hard to imagine. Latent-X2’s approach is completely different. The researchers targeted 18 different targets and had the model generate only 4 to 24 candidate molecules for each one.

The result was a 50% success rate at the target level. This means if you pick a new target and have the model compute a few dozen molecules, you have a 50% chance of finding an effective candidate. And the affinity of these molecules was in the picomolar to nanomolar range—an activity level that’s good enough to move directly to the next stage.

The Real Test: Immunogenicity

For any protein-based drug, immunogenicity is the sword of Damocles hanging over its head. If a patient’s immune system recognizes the drug as “foreign,” it could at best become ineffective and at worst trigger a fatal immune storm. In the past, we’ve used various computational tools to predict immunogenicity, but experiments are the only way to know for sure.

The most impressive part of this work is that they actually did the experiments. The researchers took the AI-generated VHH antibodies (targeting TNFL9) and cultured them with T cells isolated from multiple human donors. This is an ex vivo experiment that simulates what might happen after the drug enters the human body.

The results showed that these T cells did not exhibit significant proliferation or release inflammatory cytokines. This isn’t just a computer score; it’s real biological evidence demonstrating that the antibodies designed by Latent-X2 have a high probability of not causing an immune reaction in humans. This is the first AI model I’ve seen that claims to solve immunogenicity and backs it up with human cell data.

“Excellent Out of the Box” Developability

It’s not enough for a molecule to have activity and safety; it also has to be “usable.” “Usable” here refers to developability:

If any one of these metrics is a problem, a project can die in the CMC (Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls) stage. Typically, these issues require tedious protein engineering to fix one by one. The molecules generated by Latent-X2 were naturally as good as or even better than already marketed antibody drugs on these developability metrics. This suggests that the model, while learning sequences and structures, has also implicitly learned the “physical rules” that determine developability.

More Than Just Antibodies

What’s more, Latent-X2’s capabilities aren’t limited to antibodies. The researchers used it to design macrocyclic peptides to attack K-Ras, a notoriously “undruggable” target. The results showed that its performance was comparable to what you would get from a trillion-scale mRNA display technology. This suggests that Latent-X2 could be a more general platform for generating binding molecules, with huge potential.

In short, this work shows us what the ideal state of AI drug discovery could look like: you input a target and directly get a candidate drug with high activity, high safety, and high developability. From lengthy screening and modification to precise design and generation, this might be what the future of drug discovery looks like.

📜Title: Drug-like antibodies with low immunogenicity in human panels designed with Latent-X2

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.20263v1