Table of Contents

- ReactGPT uses a clever “in-context tuning” method, employing chemical fingerprints as a “cheat sheet,” to teach large language models how to write detailed experimental procedures for chemical reactions, just like an experienced chemist.

- The DeepDOX1 framework combines first-principles physics with deep learning to offer a more accurate and generalizable solution for predicting drug-protein affinity.

- The M2N model mimics a chemist’s macro-to-micro analytical approach—looking at functional groups and residues first, then focusing on atoms—to provide a more precise perspective on drug-target affinity prediction.

- This work takes a different path, using the chemical prior knowledge of large language models to directly guide Bayesian optimization, eliminating the need to build an explicit surrogate model and making molecular discovery more efficient.

- HD-Prot innovatively uses continuous structure tokens to solve the information loss caused by discretization, achieving high-fidelity, low-cost joint modeling of protein sequence and structure.

- BGCat leverages protein language models to accurately predict the chemical products of massive, unknown biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), addressing a major bottleneck in natural product discovery.

1. ReactGPT: Teaching Large Models to Understand Chemical Reactions Like a Chemist

We work with chemical reactions every day, but documenting the experimental process is a tedious job. Writing down the reactants, reagents, solvents, temperature, time, and workup steps in an electronic lab notebook (ELN) is not only time-consuming but also prone to error. Now, what if you had an AI assistant that could automatically generate a detailed, standardized experimental report from just a reaction equation?

This is exactly the problem ReactGPT aims to solve. Large Language Models (LLMs) are great at handling natural language, but they don’t understand chemistry. If you give one a reaction equation, it just sees a string of symbols, not the complex physical and chemical processes behind them.

The researchers’ approach is direct: we’re not going to train a “chemist” LLM from scratch—that’s too expensive. Instead, let’s take an “intern” (like GPT-4), teach it how to look up information, and have it write reports by imitation. This method is called In-Context Learning.

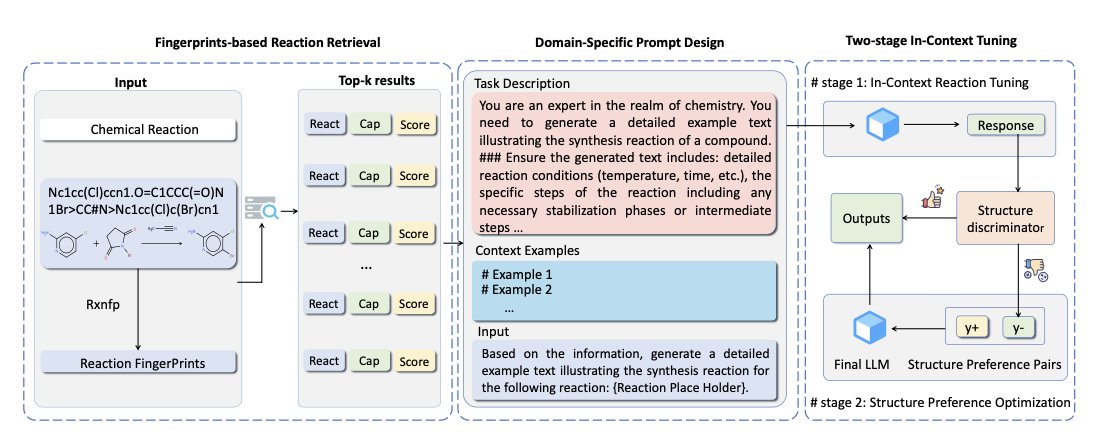

ReactGPT’s workflow has three steps:

First, retrieve similar reactions using chemical fingerprints. Every chemical reaction has a unique “fingerprint,” a numerical code that represents the structure of the reactants and the changes they undergo. Given a new reaction, ReactGPT first calculates its fingerprint and then searches a large reaction database to find a few similar “precedent” reactions. This is like telling an intern, “Don’t start writing yet. First, go see how the senior scientists documented similar experiments.”

Second, design a domain-specific prompt. Simply asking a large model to “describe the reaction” won’t work. You need to give it a clear template specifying what information to output, such as “Reactants,” “Catalyst,” “Solvent,” “Temperature,” “Product,” and “Yield.” This is like giving the intern a standardized report form to fill out, ensuring no key details are missed.

Third, use two-stage in-context tuning. This is the core of the process. ReactGPT bundles the similar reaction examples from the first step with the prompt template from the second step and feeds them all to the large model. This happens in two phases: first, the model learns the general “grammar” and format of reaction descriptions, and then it focuses on the details of the specific reaction at hand. The entire process is done dynamically “in-context,” without retraining the model. It’s like an intern who, after reviewing a few examples, immediately starts writing the new report, applying what they just learned.

And the results? ReactGPT achieved state-of-the-art performance on both reaction captioning (generating reaction descriptions) and predicting experimental procedures. The text it generates is not only chemically logical but also follows the writing conventions of human chemists.

From the perspective of an R&D scientist, ReactGPT’s value lies in its pragmatic, engineering-focused solution. It doesn’t try to make an LLM “understand” chemistry from thin air. Instead, it cleverly combines the language capabilities of LLMs with existing chemical knowledge bases. The model’s performance heavily depends on the quality of the database it can access. If the “examples” in the database are poor, the AI won’t produce anything impressive.

This framework’s potential also goes beyond automating lab notes. If a model can accurately describe a reaction in the “forward” direction, it’s one step closer to predicting synthesis routes in the “reverse” direction (retrosynthesis). This has enormous value for designing and synthesizing new molecules in drug discovery.

📜Title: ReactGPT: Understanding of Chemical Reactions via In-Context Tuning 🌐Paper: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/31983/34138

2. DeepDOX1: AI + Quantum Mechanics Transforms Drug Affinity Prediction

Predicting the binding strength, or affinity, between a drug molecule and its target protein has always been a central challenge in drug development.

Traditional scoring functions are fast but not very accurate. Purely physics-based simulations, like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), are accurate but far too slow—calculating a single molecule can take days. In recent years, AI models have shown promise, but everyone is a bit wary of them. They act like black boxes, and generalization is a major issue. A model trained well on kinases might fail completely when applied to GPCRs.

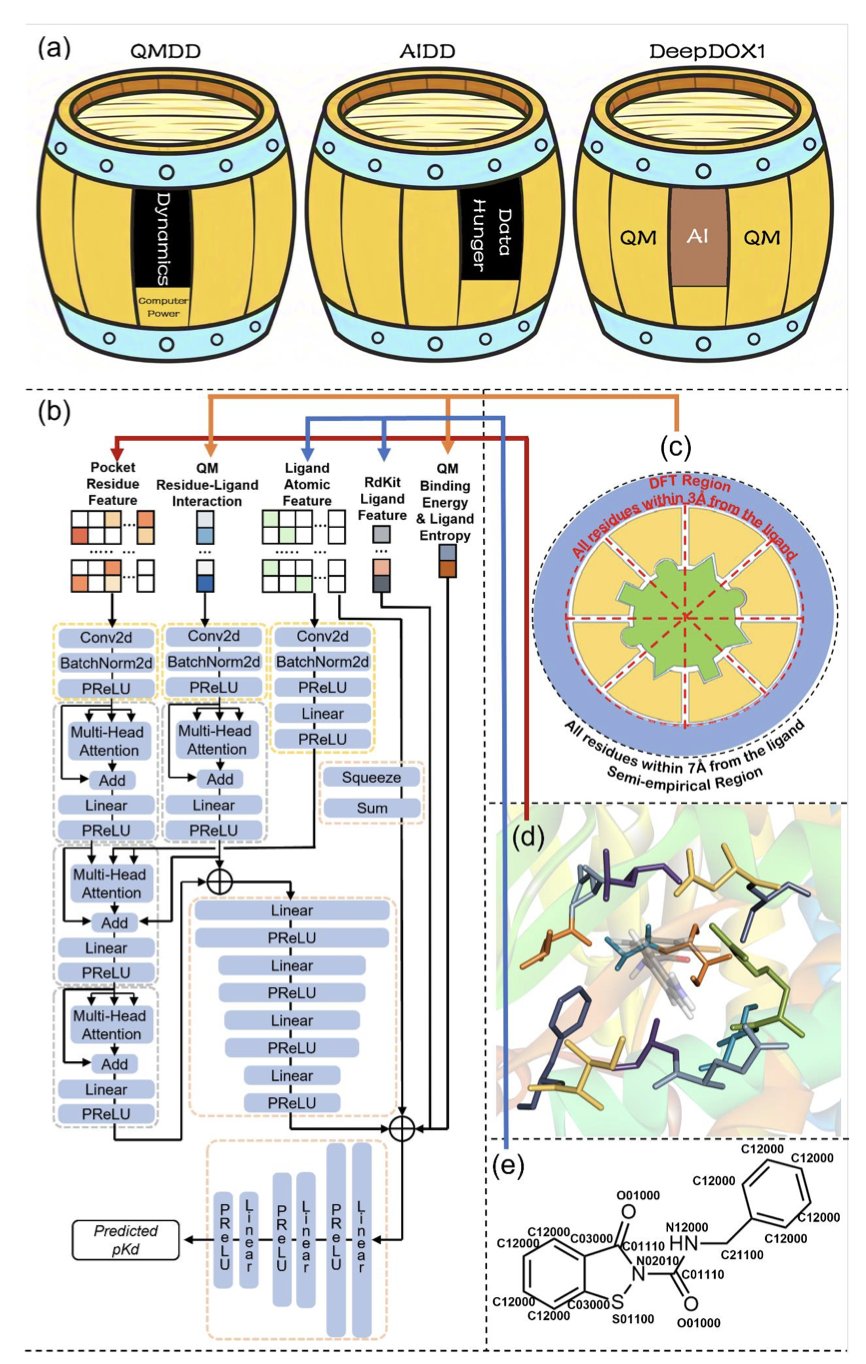

The approach in this DeepDOX1 paper is interesting. It doesn’t let AI work alone. Instead, it creates a “dual-drive” framework where physics and AI each play to their strengths.

Here’s how you can think about it: the researchers first use Quantum Mechanics (QM) calculations to generate a “static” interaction map between a drug molecule and the protein’s binding pocket. This is like creating a blueprint based on first principles of physics, describing the fundamental forces between atoms.

But the real binding process is dynamic. It involves solvent effects and changes in the protein’s conformation. Calculating these complex, “dynamic” factors with QM would take too long. So, they trained a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). This AI model’s job isn’t to predict affinity from scratch, but to learn how to make “corrections” to the physics blueprint. It learns the “dynamics correction,” which is the difference between the QM-calculated value and the actual experimental value.

The benefits are clear. First, the model is built on a “skeleton” of physics, so what it learns has physical meaning instead of just being a data fit. This makes it more reliable when facing new situations. Second, because the heavy lifting is done by QM, the AI architecture can be quite simple. They trained it with fewer than 10,000 data points, which is a breath of fresh air in a field where deep learning often requires millions of data points. This also explains why it generalizes so well.

The paper mentions some tough cases, like covalent inhibitors, halogenated ligands, and metalloproteins. These are all headaches for traditional computational methods. The formation of covalent bonds, the specific directionality of halogen bonds, and the complex coordination fields of metal ions often trip up standard scoring functions. The fact that DeepDOX1 performs well in these scenarios shows that its QM-based feature extraction really captures the key physicochemical interactions.

What convinced me most was their experimental validation. They used DeepDOX1 to design new covalent inhibitors for human fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (hu-FBPase). The results showed that the new molecules did indeed have improved binding affinity. More importantly, they solved the crystal structure of the complex and found that the actual binding mode was highly consistent with the model’s prediction. This is what’s known as “closed-loop validation”—from computational prediction to wet-lab confirmation. It’s the gold standard for measuring whether a computational tool has practical value.

This approach of combining AI with first-principles physics could be a new direction for computational drug design. It’s not about replacing physics with AI, but about using AI to accelerate and refine physics-based simulations. DeepDOX1 offers a tool that is cost-effective and highly generalizable. And they’ve made a web server available, which is great because it lets more people try it out quickly.

📜Title: DeepDOX1: A Dual-Drive Framework Integrating Deep Learning and First-Principles Physics for Drug-Protein Affinity Prediction 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.12.693818v1

3. The M2N Model: From Macro to Micro, Predicting Drug Binding Like a Chemist

In drug R&D, we deal with affinity every day. A molecule’s Kᵢ or IC₅₀ value directly determines whether it’s a promising lead or a dead end. If we could accurately predict the binding affinity of a small molecule to a target protein using a computational model, we could save a huge amount of time and money on synthesis and testing.

Many models do this now, but most are caught in a dilemma. They either look only at the macro level—treating amino acid residues or drug functional groups as single units—which is fast but loses too many critical atomic-level details, or they dive straight into atom-level calculations, which captures detail but can overlook overall structural features and is computationally massive.

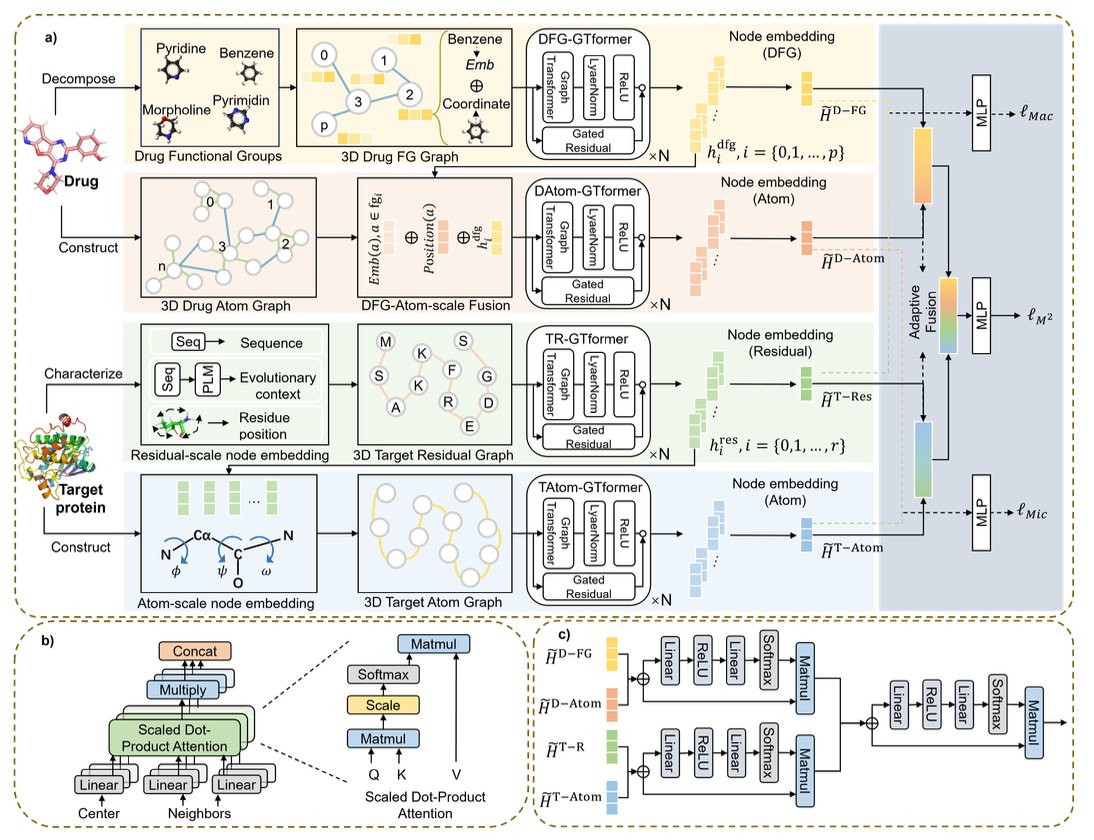

This new model, called M2N, has an interesting approach. Its logic is a lot like our own intuition in research. You don’t start by fixating on a single atom; you first get the big picture. It’s like using Google Maps: you start with the city view (macro), find the target neighborhood, and then zoom in to the street level to find the specific address (micro).

Here’s how it works:

First, the macro analysis. For the protein, the model identifies key amino acid residues in the binding pocket and treats them as individual nodes. These “big chunks” define the basic shape and chemical environment of the pocket. For the small molecule drug, the model also starts by looking at its functional groups, like phenyl rings, carboxyl groups, or amines. These are the key “components” that determine the molecule’s properties and interaction patterns.

Second, the micro refinement. After establishing connections at the macro level, the model “drills down” and breaks apart each residue and functional group into its constituent atoms. This allows it to see more fine-grained interactions, like which hydrogen atom forms a hydrogen bond with which oxygen atom, or which two carbon atoms have a van der Waals interaction.

The most clever part is how it combines the macro and micro information. The researchers designed something called an Adaptive Fusion Module (AFM). You can think of it as a project manager. Based on the specific drug-target complex, it decides whether the overall shape of the pocket is more important or if a particular atom-to-atom interaction is more critical, and then it assigns different weights to them. Through learning, the model masters this art of balancing priorities.

The researchers tested M2N on two commonly used industry datasets, DAVIS and KIBA, and the results showed it outperformed several current mainstream methods. But for me, the most interesting part is their claim about generalization. It’s not surprising for a model to perform well on data it was trained on. The real test is whether it can accurately predict for a target it has never seen before, or for a molecule with a completely new chemical scaffold. This directly impacts whether it’s actually useful in our projects—can it help us sift through millions of virtual molecules to find those few with real potential?

📜Title: M2N: A Progressive Macro-to-Micro 3D Modeling Scheme for Unveiling Drug-Target Affinity 🌐Paper: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/32039/34194

4. A New Way to Use LLMs: Skip the Surrogate Model and Directly Guide Molecular Discovery

In drug discovery, we are constantly playing a game of “finding a needle in a haystack.” Chemical space is unimaginably vast, and the ideal drug molecule is hidden somewhere within it. Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a common tool we use to navigate this space. Its logic is simple: first, build a “map” based on existing data (the surrogate model). Then, use this map to predict which unknown region is most likely to contain “treasure” (using an acquisition function). Next, explore that region, get new data, and update the map. This cycle repeats.

This process sounds good, but the problem is in the first step—building the surrogate model. When molecular structures are complex and the data is high-dimensional, this model is not only difficult to build but also often inaccurate. It’s like setting out on a treasure hunt but spending most of your time drawing a blurry, unreliable map.

The authors of this paper proposed an interesting idea: what if we could just skip the map-drawing step altogether?

They developed a new method called LLMAT. The core idea is to stop trying to build a complete surrogate model. Instead, it directly uses the “chemical intuition” already present in large language models and chemical foundation models to tell the acquisition function where to go next.

Here’s how it works:

First, LLMAT doesn’t view chemical space as a flat field. It organizes it into a tree. Imagine the root of the tree is the set of all molecules. As you move down, the branches represent more specific classes of molecules, and the leaves are individual molecules. For a computer, a tree structure is much easier to process than a disorganized space.

Next, they use the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm to “prune” this tree. MCTS became famous with AlphaGo and is especially good at finding optimal paths in huge decision spaces. Here, it helps the algorithm explore down the most promising “branches” instead of wandering aimlessly through the entire “forest.”

Now for the cleverest part. Before starting the detailed search, LLMAT uses a large language model to perform a quick “coarse-graining” of the molecules. It has the LLM divide the molecules into several large clusters based on their predicted properties, such as a “high-activity zone,” a “toxic zone,” or a “poor-solubility zone.” This allows the algorithm to focus its valuable computational resources on the most promising cluster, the “high-activity zone,” significantly reducing wasted exploration.

This is like an experienced chemist who can tell you with just a glance, “Don’t waste your time over there; those classes of compounds are a dead end. Focus on these few scaffolds over here.” The LLM plays the role of this senior expert. It doesn’t provide a precise map, but it offers invaluable “prior knowledge.”

What were the results?

The researchers tested LLMAT on several real-world chemical datasets. The results showed that LLMAT outperformed traditional Bayesian optimization methods, as well as some other LLM-based approaches, in both sample efficiency (finding good molecules with fewer experiments) and computational efficiency.

From an R&D scientist’s perspective, this approach is very practical. It doesn’t try to solve everything with one giant model. Instead, it smartly combines the macro-level knowledge of an LLM with the search capabilities of MCTS. It bypasses the most troublesome part of traditional BO—the surrogate model—making the entire optimization process more direct and efficient. In a real drug discovery project, this could mean finding promising candidate molecules faster and at a lower cost.

📜Title: Informing Acquisition Functions via Foundation Models for Molecular Discovery 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.13935

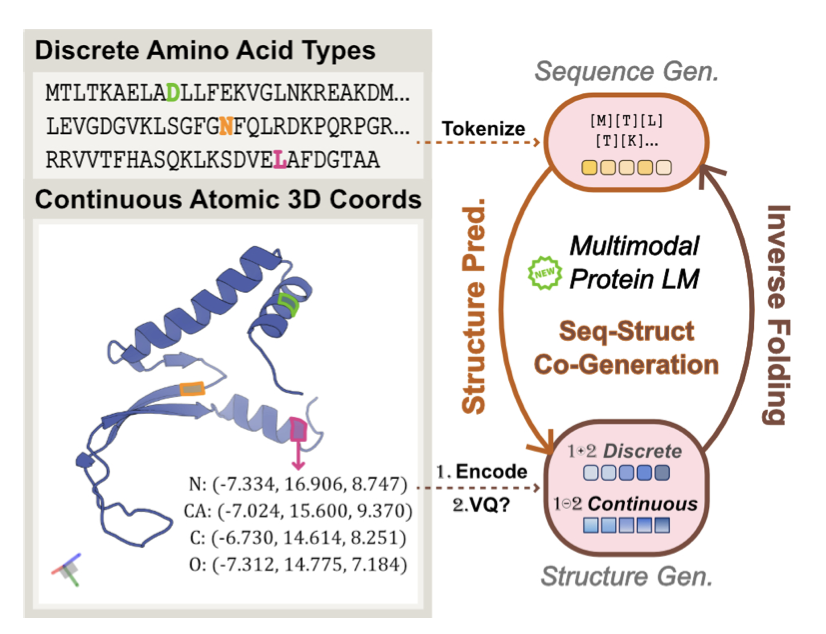

5. HD-Prot: Continuous Tokens Are a New Paradigm for Protein Modeling

In the world of protein language models (pLMs), we’ve been dealing with a fundamental conflict: protein sequences are discrete, made up of 20 amino acids like an alphabet, while protein structures are continuous, defined by the precise coordinates of atoms in 3D space. To make these two “talk” to each other, past models often took a simple but crude approach: they “quantized” the continuous 3D structure into discrete tokens. This is like forcing a high-resolution photograph into a mosaic. You can see the general shape, but a huge amount of fine detail is inevitably lost.

This work on HD-Prot is a brilliant counterattack on this “mosaic” method. The researchers asked a simple question: why do we have to lose information? Can’t we just model the structure directly in continuous space?

Here’s how it works:

First, the model needs a “translator” that can understand and encode continuous 3D structures. The researchers designed a non-quantizing autoencoder to serve as the structure tokenizer. This tokenizer’s job is to compress complex protein coordinates into a compact, continuous mathematical representation (a token) and, crucially, to be able to losslessly reconstruct the original structure from that representation. Think of it like using a vector graphic instead of a pixel image—no matter how much you zoom in, the details never get distorted. This is the cornerstone of the method’s high fidelity.

Next came the real challenge: how to make a single model handle two completely different data types—discrete sequence tokens and continuous structure tokens. HD-Prot uses a unified absorbing diffusion process to solve this. You can think of it as a bilingual expert that can understand and generate both “languages” simultaneously.

For the discrete amino acid sequence, it uses a categorical prediction method, like filling in the blanks. For the continuous structure tokens, it uses a continuous diffusion model, which works by starting with noise and progressively denoising it to restore the true structure. These two processes are cleverly integrated into a single framework, allowing the model to learn the underlying physicochemical laws that connect sequence and structure.

What are the practical benefits?

HD-Prot has shown highly competitive performance on several tasks. 1. Sequence-Structure Co-generation: The model can design entirely new, chemically plausible protein sequences and their corresponding stable 3D structures from scratch. 2. Motif-scaffolding: This is a highly valued capability in drug design. You can give the model a small functional fragment (like a drug-binding site) and have it design a complete protein scaffold to stabilize and present that motif. 3. Structure Prediction and Inverse Folding: Its performance on these traditional tasks is also quite good.

The most critical point is that HD-Prot achieves these results with a significantly lower computational cost. In an era where training models often requires massive amounts of computing power, this efficiency advantage means that more labs and research teams can afford to use this technology, which could accelerate progress across the entire field.

From my perspective, the value of HD-Prot isn’t just that it’s a high-performing new model, but that it offers a new way of thinking. It proves that in multimodal protein modeling, we don’t always have to compromise for the convenience of discretization. By embracing continuous space, we may find a path to modeling that is more elegant, more efficient, and closer to the true nature of biology.

📜Title: HD-Prot: A Protein Language Model for Joint Sequence-Structure Modeling with Continuous Structure Tokens 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.15133v1

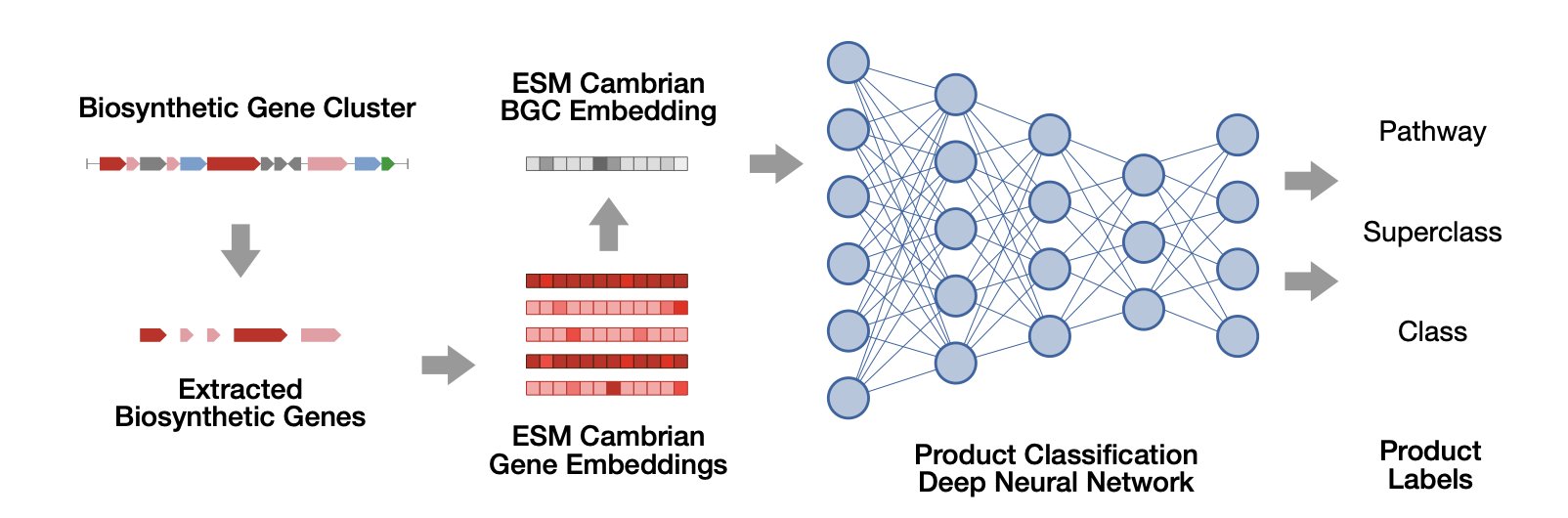

6. BGCat: AI Accurately Predicts Gene Cluster Products, A New Tool for Natural Product Discovery

In the field of natural product R&D, we are sitting on a massive treasure chest. Microbial genomes are filled with countless Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs), which are the “chemical factories” that produce all sorts of complex molecules. The problem is, the map we have is blurry. We can see where these “factories” are, but most of the time, we have no idea what they are actually making.

Traditional prediction tools, like antiSMASH, can give a rough classification, like “this is a polyketide synthase (PKS) gene cluster.” That’s useful, but it’s not enough. It’s like being told a factory makes “cars,” but you don’t know if it’s building sedans, trucks, or sports cars. For drug development, those details are crucial.

Now, a new paper introduces a tool called BGCat, which is like adding a high-resolution lens to our map.

How BGCat works is simple

The authors start with a pre-trained protein language model, ESM Cambrian. You can think of this model as an expert fluent in the “language of enzymes.” It can read the amino acid sequence of each enzyme in a BGC and understand its function.

You input all the gene sequences from a gene cluster, and the language model generates a numerical vector, or “gene representation,” for each one. This vector captures the core functional information of the gene. Then, a deep neural network takes these vectors, analyzes the configuration of the entire “factory,” and predicts which specific class of chemical molecule it is most likely to produce.

This process moves beyond the old limitations of relying on single homologous gene comparisons and instead understands the functional potential of the BGC as a whole.

How to solve the chronic problem of insufficient data

Machine learning models need a lot of data to train, but the number of known “BGC-product” pairs is very limited. This has been a long-standing problem in the field.

The researchers came up with a clever solution: a clustering-based augmentation strategy. They first group functionally similar BGCs into clusters. If one member of a cluster has a known product, they assume that other members will likely produce structurally similar molecules.

By doing this, they “created” more effective training samples for the model. It’s like teaching a child to recognize animals. If you only have a picture of a golden retriever, you can tell them that other dogs that look a lot like it are also dogs. This greatly improved the model’s generalization ability and prediction accuracy.

What practical value does BGCat bring?

First, the authors used BGCat to analyze over 100,000 BGCs in the antiSMASH database that previously had only vague annotations. Overnight, we gained a much more detailed understanding of the chemical potential of the microbial world. Many gene clusters that were previously labeled “unknown” now have specific predicted labels, like “Type I aromatic polyketide” or “lactone.” This gives us direct leads for finding novel natural products.

Second, they proposed a new concept called “Product Class Profiles” (PCPs). In the past, we tended to assign a single, fixed functional label to a Gene Cluster Family (GCF). But PCPs suggest that a family’s function is more like a probability distribution. For example, a certain GCF might have a 70% chance of producing a macrolide, a 20% chance of producing an enediyne, and a 10% chance of producing something else.

This perspective is more aligned with biological reality. A gene cluster family undergoes various changes during evolution, and its function can drift. PCPs accurately capture this diversity, bringing us a step closer to a deeper understanding of BGC function.

BGCat is a powerful tool. It can help us more quickly screen massive amounts of genomic data to find the most promising candidate BGCs, allowing us to focus our efforts on exploring the unknown chemical space that holds real therapeutic potential.

📜Title: Fine-Grained Structural Classification of Biosynthetic Gene Cluster-Encoded Products 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.12.693975v1