Table of Contents

- By giving a multi-task learning model a special “sparse mask,” we not only improved toxicity prediction accuracy but also, for the first time, could see the chemical basis for the AI’s judgments.

- EnzEngDB provides a platform that integrates data storage, 3D visualization, and AI-driven data extraction, solving the problem of scattered and underutilized data in enzyme engineering.

- This work shows how a language model designed for protein pairs can efficiently predict interaction, affinity, and binding interfaces from sequence alone, in some cases outperforming structure-based methods.

- The Trio framework cleverly combines three AI technologies to solve a long-standing problem with generative models, making AI-designed molecules more like those designed by humans and with better drug potential.

- The UNAAGI model uses atom-level diffusion to let AI design proteins with non-canonical amino acids, essentially applying small-molecule drug design principles to protein engineering.

- Using generative AI (specifically GANs) to augment small peptide datasets can significantly improve the accuracy of function prediction models, especially when experimental data is limited.

1. AI Predicts Molecular Toxicity: More Accurate, and Now Explainable

In computational toxicology, we often face a frustrating problem: a model tells us a molecule is “toxic” but doesn’t explain why. It’s like an experienced medical examiner giving a conclusion without the reasoning. That doesn’t help medicinal chemists on the front lines. What we need to know is which part of the molecule is the culprit.

This paper offers a clever solution.

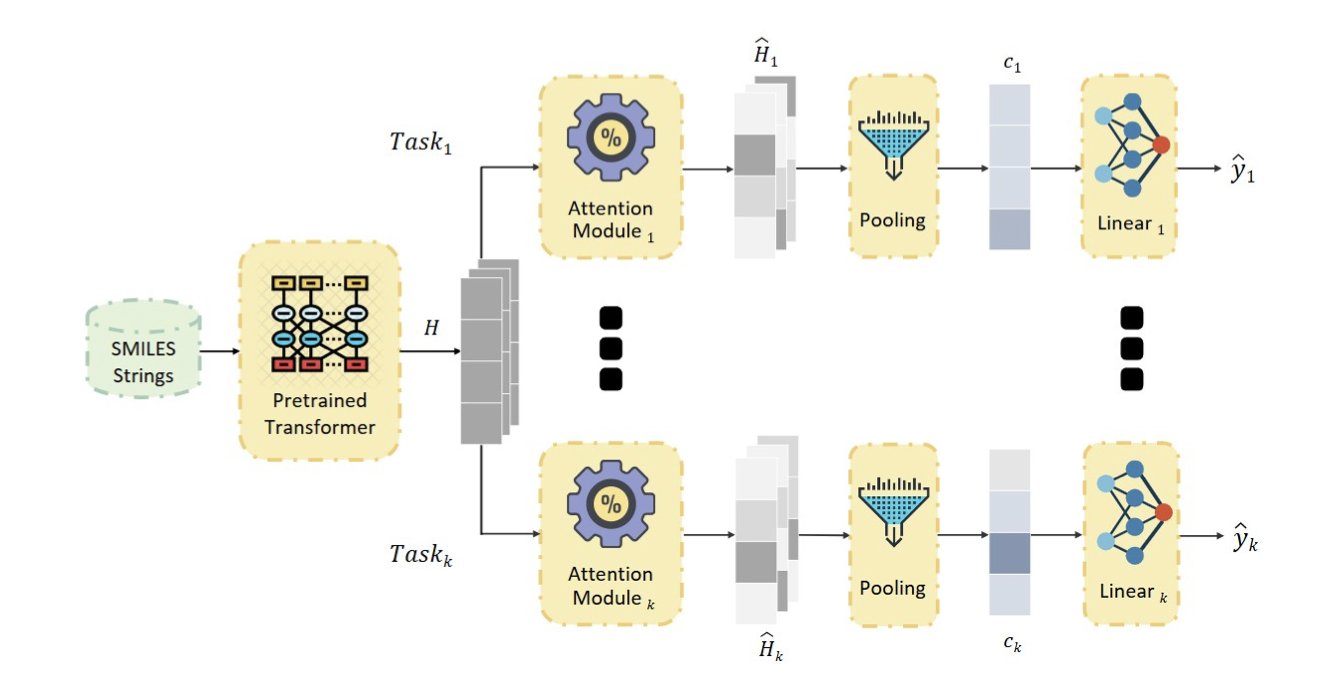

First, the researchers used a framework called Multi-task Learning (MTL). You can think of it as teaching one AI model to recognize many different types of toxicity at once—like liver toxicity, cardiotoxicity, and carcinogenicity. The goal is for the model to learn the general, underlying principles connecting chemical structure to toxicity, rather than just memorizing patterns for a single task.

But MTL has a common problem: negative transfer. Sometimes, learning about task A can interfere with making judgments on task B. It’s like a student who has learned too many disconnected facts and mixes them up during an exam.

The first highlight of this paper is how it solves this. Their architecture has all tasks share a powerful chemical language model as a “brain” to understand the basic language of molecules. Then, each specific toxicity task gets its own separate “attention module.” The brain handles the input, and each attention module handles the output in its own domain. This way, they can share knowledge without getting in each other’s way.

The second and most central innovation is adding an L1 sparse penalty to each attention module. This might sound technical, but the principle is simple. Imagine giving the model a pen with very expensive ink. When analyzing a molecule’s structure, it can’t scribble everywhere. It has to use its limited ink sparingly, marking only the one or two atomic groups most relevant to a specific toxicity.

The result was unexpected. Usually, we assume that adding more constraints to a model will decrease its performance, like accuracy. But here, this “sparse mask” not only made the model’s predictions explainable—we can clearly see which part of the molecule it focused on—but it also made the predictions more accurate.

Why? Because it forces the model to learn actual causal relationships instead of relying on coincidences in the data. The model stops memorizing that “molecules that look like this are toxic” and starts learning that “because this molecule has a nitroaromatic ring, it might have this specific toxicity.”

Look at the visualization in the image. For the same molecule, the model focuses on completely different regions when predicting different toxicity endpoints. This perfectly matches the intuition of a medicinal chemist. Even better, for different molecules that contain the same toxicophore, the model can accurately identify it.

This changes the tool from a black box that just gives “yes” or “no” answers into an intelligent partner we can talk to. It can tell us: “I think this compound has a risk of liver toxicity, and the problem might be this amide group here. Have you considered modifying it?”

This is what AI-assisted drug discovery should look like. It provides not just a cold score, but a chemically meaningful insight that can guide the next step in molecular design.

📜Title: Task-Specific Sparse Feature Masks for Molecular Toxicity Prediction with Chemical Language Models

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.11412v1

2. EnzEngDB: Integrating Data and AI to Accelerate Enzyme Engineering

Anyone in enzyme engineering shares a common frustration: the data is too scattered.

Data from each lab and every paper is like an isolated island. We create dozens of mutants and measure their activity and stability, but most of this valuable data ends up confined to lab notebooks or supplemental materials. Trying to compare data from different studies or systematically analyze which mutations actually work is an almost impossible task.

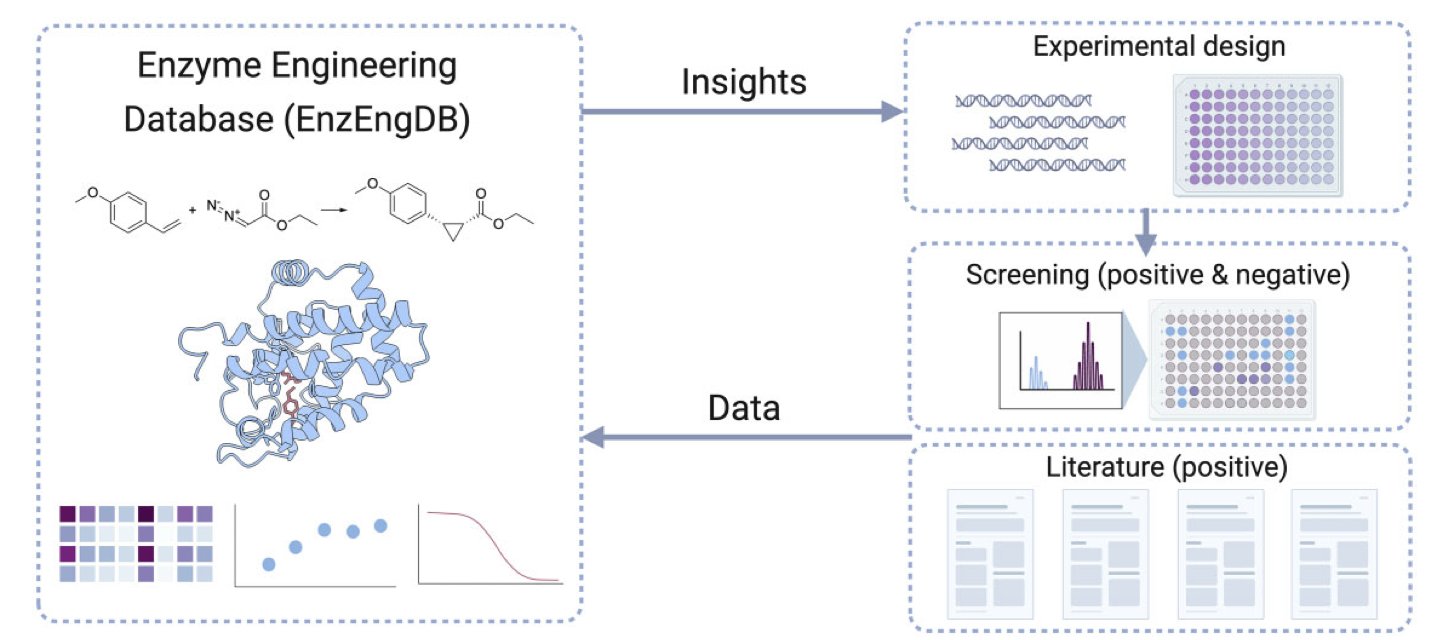

The new EnzEngDB platform seems designed to solve this core problem. It’s not just a data repository but a tool built for the enzyme engineering workflow.

First, it creates a standardized data framework. The most critical information for an enzyme engineering project—like amino acid sequence, the reaction catalyzed (represented by reaction SMILES, which is key), and performance metrics (like yield or kcat/Km)—can all be systematically recorded. This means if you’re studying a specific enzyme family, like ketoreductases, you can integrate data from dozens of mutants from different sources for a side-by-side comparison. What used to take weeks of sifting through literature can now be done on one platform.

Its real highlight is the interactive 3D visualization tool. This is the feature most likely to impress researchers on the front lines. Suppose you’ve found 10 mutants with improved activity. Looking at a list like A123G or F45Y makes it hard to spot a pattern. But if you map these mutation sites directly onto the protein’s 3D structure, everything changes. You might instantly see that all the high-activity mutations are clustered at the entrance of the substrate binding pocket. This discovery immediately gives you a clear direction for your next experiment: maybe you should systematically engineer this entrance to optimize substrate entry and exit. This closed loop—from data to structure to a new hypothesis—is key to accelerating research. It turns abstract sequence information into intuitive, actionable structural insights.

Another clever feature is its use of Large Language Models (LLMs) to automatically extract data from literature. Manually curating data from papers is incredibly tedious and time-consuming, and it’s the bottleneck for building any database. The researchers trained an LLM to read papers and extract key sequence-function data. To ensure quality, they also built a “gold standard” dataset to validate the AI’s accuracy. While the AI may not be 100% perfect, even if it can handle 80% of the initial curation, it frees up a massive amount of human effort and allows the database to grow much faster in both speed and scope.

Finally, the authors considered data privacy. The platform supports both public and private deployment. Sensitive corporate data can be analyzed using the tool on a local server, while public data can be contributed to the community. This practical model should help the tool get adopted. A good database needs a community to build it, and EnzEngDB provides an excellent starting point.

📜Title: Enzyme Engineering Database (EnzEngDB): a platform for sharing and interpreting sequence–function relationships across protein engineering campaigns

🌐Paper: https://academic.oup.com/nar/article/doi/10.1093/nar/gkaf1142/8373944

3. PPLM: Can AI Predict How Proteins Interact Without Looking at 3D Structures?

In drug discovery, we’re always playing a highly complex Lego game. We want to know if two protein “bricks” can fit together, how tightly they’ll bind, and where they make contact. Traditionally, we thought we needed the precise 3D blueprint (the protein structure) for each brick to answer these questions. Getting structures is expensive and slow. AlphaFold solved the problem of getting the blueprint for a single brick, but understanding how two bricks interact is another huge challenge.

Now, a new paper on a Protein-Protein Language Model (PPLM) suggests we might not need to rely so much on those 3D blueprints.

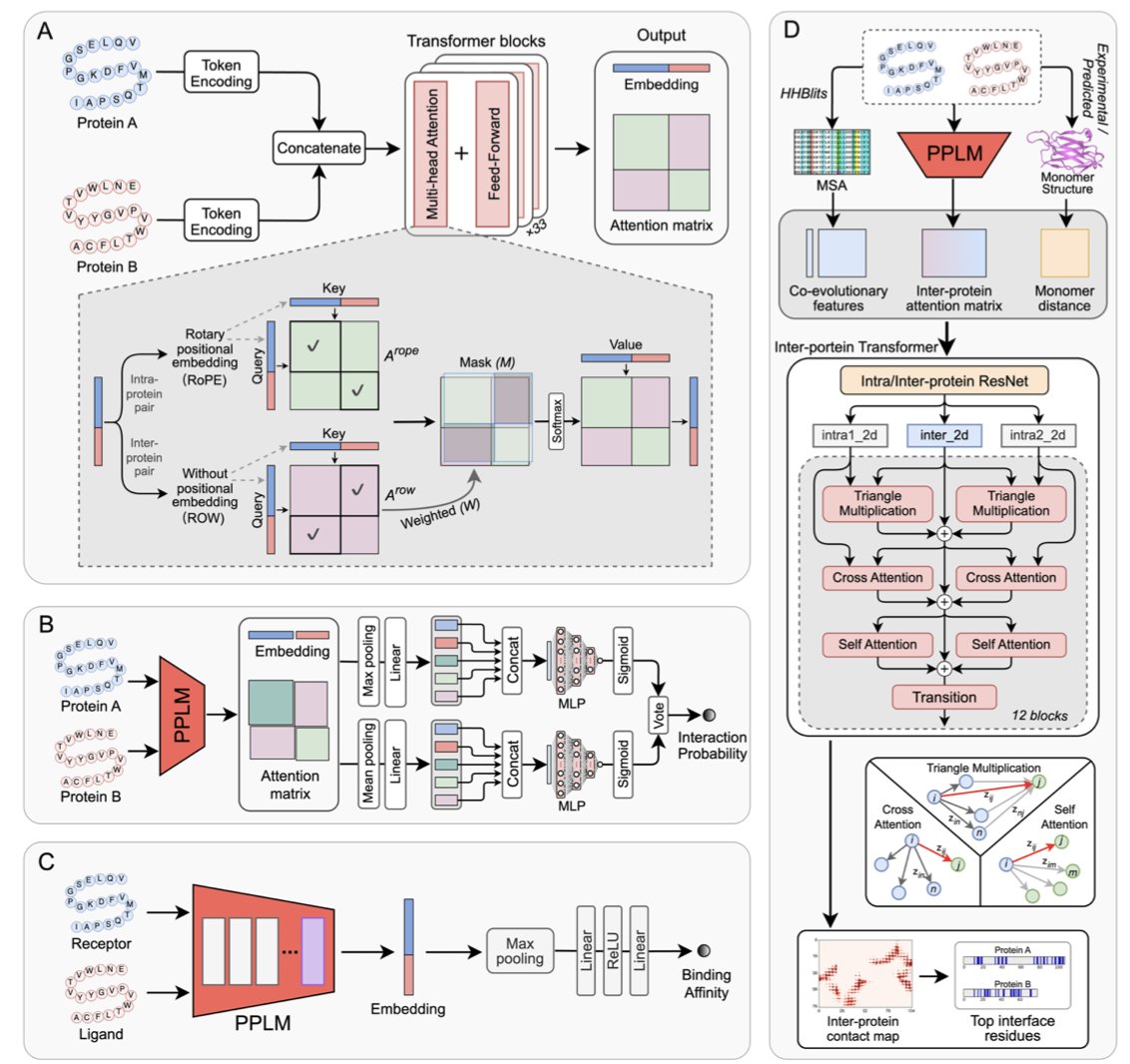

The Core Idea: From “Monologue” to “Dialogue”

Previous protein language models, like the well-known ESM2, were like linguists analyzing one person’s speech. They are good at understanding the grammar and vocabulary of a single protein (its amino acid sequence), but asking them to understand a “dialogue” between two proteins is a stretch. They could read two “speeches” separately and then guess if the two were communicating.

PPLM takes a completely different approach. It feeds the sequences of two proteins together from the very beginning, letting the model learn their shared linguistic patterns directly. It’s like having the AI listen to a recording of a two-person conversation instead of their individual monologues. The model’s internal attention mechanism is also designed in a hybrid mode. It can focus on the internal structure of each protein (intra-protein attention) and, at the same time, on the regions where the two proteins might interact (inter-protein attention). This allows the model to figure out for itself which amino acid residues are key for cross-protein communication during unsupervised pre-training.

How does it perform in practice?

The study used PPLM to build three specialized models to answer our three main questions:

Will they bind? (PPLM-PPI)

This model acts like a molecular matchmaker. The results show it achieved top-tier performance in determining whether two proteins interact, and it was consistent across datasets from different species. This is critical for mapping complex signaling networks in the cell and finding new drug targets.How strong is the binding? (PPLM-Affinity)

This is the part that gets drug developers excited. Predicting binding affinity is a core, and very difficult, part of drug design. PPLM-Affinity not only surpassed ESM2 but, in some tests, even beat methods that rely on 3D structures. Its performance was particularly strong on flexible complexes like antibody-antigen pairs, which have many conformational changes. This means we might be able to screen and optimize antibody drugs on a large scale in a faster, less computationally expensive way.Where do they bind? (PPLM-Contact)

Knowing that two proteins bind isn’t enough; we also need to know the specific binding sites to design small molecules or peptides to interfere with them. PPLM-Contact also outperformed existing methods in predicting the contact residues between proteins.

What’s more interesting is that the researchers created an upgraded version, PPLM-Contact2. They fused the “interaction knowledge” learned by PPLM from sequences with the complex structure information predicted by AlphaFold. The result? This “hybrid” model beat the latest AlphaFold2.3 and AlphaFold3 on the contact prediction task.

This points to an important trend: neither pure sequence models nor pure structure models may be the final answer. Real power comes from intelligently combining the two. Sequence models can efficiently learn the “chemical intuition” of interactions from massive amounts of data, while structure models provide precise physical constraints.

For people on the front lines of drug discovery, a tool like PPLM is very valuable. It means we can run larger-scale, faster virtual screens before doing experiments to narrow down candidates and focus our valuable lab resources on the most promising molecules. This once again proves that great AI models can extract deep physical and chemical principles governing 3D interactions from seemingly simple 1D sequence data.

📜Title: A Corporative Language Model for Protein–Protein Interaction, Binding Affinity, and Interface Contact Prediction

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.07.663595v2

4. The Trio Framework: A New Approach to AI Molecular Discovery for Better Drug Design

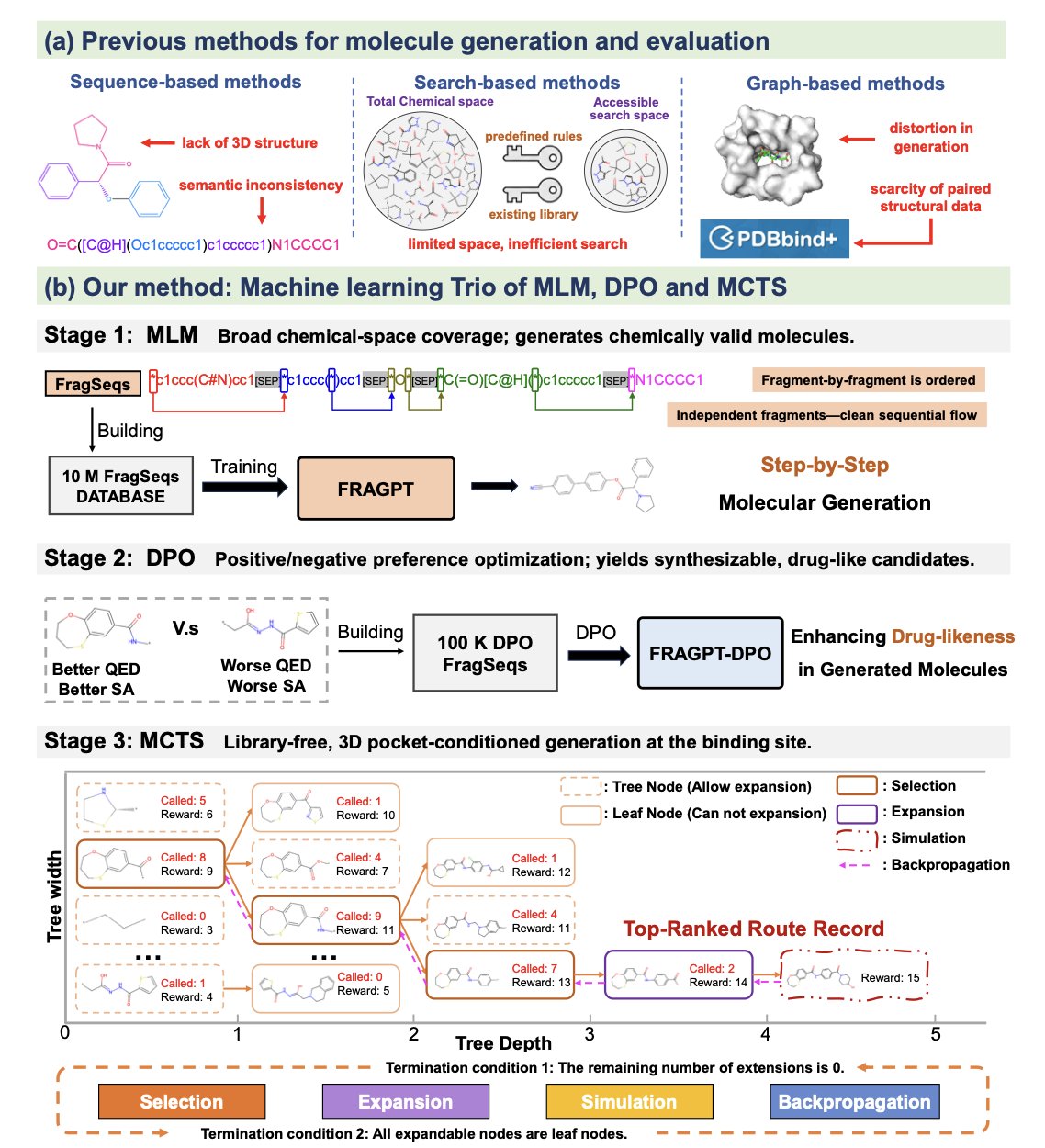

In drug discovery, we often work with various AI generative models. These models can quickly generate tons of new molecular structures, but often, they’re like an artist who doesn’t know the rules of chemistry. The molecules they design are either extremely difficult to synthesize or have terrible drug-like properties. We spend a lot of time sifting through and modifying these results.

A recent paper proposed a framework called Trio with an interesting approach. It doesn’t invent a new algorithm. Instead, it combines three established technologies like Lego bricks: a fragment-based language model, reinforcement learning, and Monte Carlo Tree Search, to try to solve these problems.

Step 1: Build molecules using a chemist’s language

The foundation of Trio is a language model called FRAGPT. It’s different from traditional generative models because it doesn’t build molecules atom by atom. It uses “molecular fragments” as its basic building blocks.

This is similar to how chemists think. When we design a molecule, we think in terms of functional groups like benzene rings, amide bonds, or hydroxyl groups, not individual carbon or oxygen atoms. Building with fragments has several direct benefits:

1. Higher chemical validity: Since the fragments are themselves stable chemical structures, the resulting molecules are less likely to have strange bond angles or unstable configurations.

2. Higher efficiency: It’s much faster to build a house with large blocks than with individual grains of sand.

The FRAGPT model was trained on the SMILES notations of millions of known molecules, learning the correct “grammar” for connecting molecular fragments.

Step 2: Give the model a clear standard for a “good molecule”

Once the model knows how to build molecules, the next step is to tell it what kind of “good molecules” we want. This is where Reinforcement Learning (RL) comes in.

The researchers defined a reward function that includes several key drug-like properties we care about, such as Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) and Synthetic Accessibility (SA).

This way, as the model generates new molecules, it naturally “evolves” toward those with better drug-like properties.

Step 3: Search the vast chemical space intelligently

The chemical space is unimaginably vast. If we just let the model generate molecules randomly, it could easily get stuck in a local optimum, repeatedly generating similar high-scoring molecules while missing out on other, more promising new scaffolds.

Trio uses Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to solve this. This algorithm is widely known for its role in AlphaGo’s success.

This strategic search ensures that Trio can not only optimize known good structures but also efficiently discover entirely new and promising chemotypes.

The results show that Trio performs quite well. Compared to current state-of-the-art models, the molecules it generates show significant improvements in binding affinity, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility—by 7.85%, 11.10%, and 12.05%, respectively. More importantly, the molecular diversity was four times greater. This means it is truly exploring a wider chemical space.

Overall, Trio offers a closed-loop system that more closely resembles our actual workflow. It builds molecules using the fragment-based language chemists are familiar with, guides the process with clear drug-like properties, and uses a strategic search to explore new territory. This “human-AI collaboration” approach may help AI-generated molecules move from the computer screen to the lab flask more quickly.

📜Title: Toward Closed-loop Molecular Discovery via Language Model, Property Alignment and Strategic Search

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.09566v1

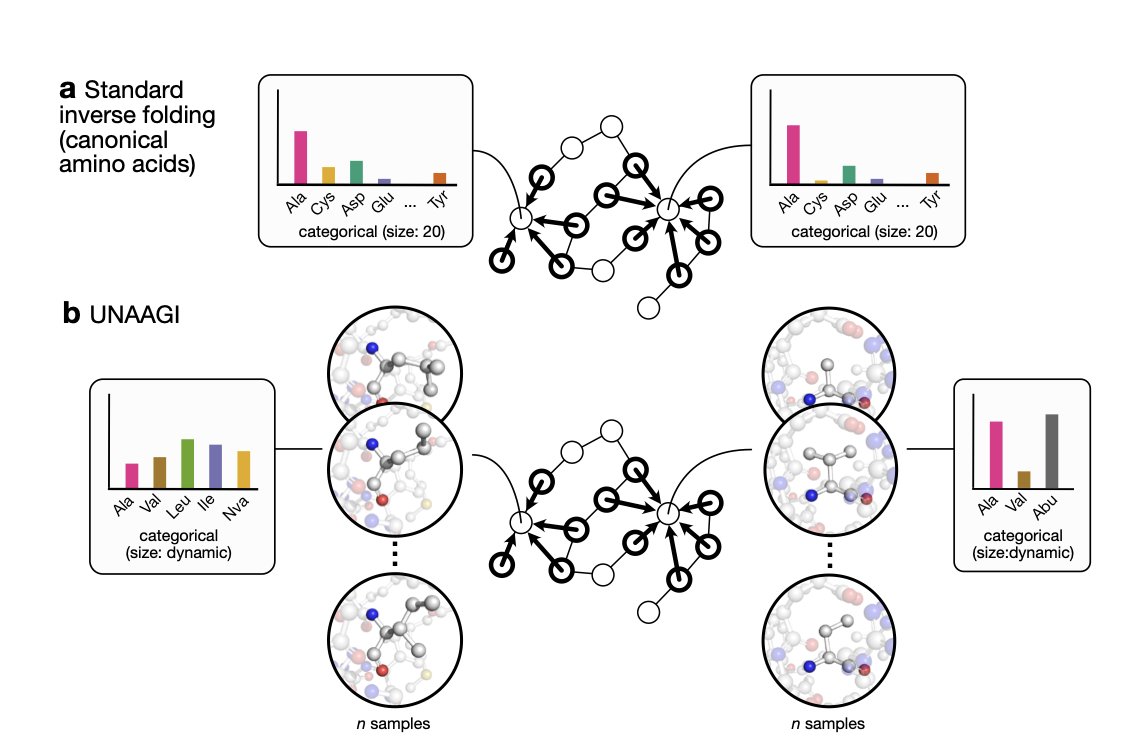

5. UNAAGI: AI Designs Non-Canonical Amino Acids at the Atomic Level

In protein engineering, our work has been like playing with a Lego set that has only 20 standard bricks. Although we can build all sorts of amazing structures, our imagination is ultimately limited by these 20 basic units. Introducing non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) is like adding hundreds or thousands of special-shaped bricks to that set, which has huge potential. But this also brings a new problem: with so many new bricks, where should we put them to get the best fit?

Traditional computational methods do reasonably well with the 20 standard amino acids, but they are often helpless when it comes to ncAAs. That’s because most of them treat an amino acid residue as a single unit, not as a collection of atoms.

Now, a new model called UNAAGI offers a completely new solution.

Its working principle is direct. Instead of trying to “swap bricks” on an existing structure like traditional methods, it does something more fundamental: it erases the amino acid at a specific position and then “redraws” it, atom by atom. This is the idea behind a diffusion model: starting from a disordered cloud of atomic coordinates and gradually generating a chemically valid and structurally compatible side chain.

The model is built on an E(3)-equivariant framework. In simple terms, this means it understands 3D space. If you rotate the entire protein, the model still knows which amino acid is best for that position. This is a fundamental requirement for any serious structural biology model.

What I find clever is how it handles side chains of different sizes. A glycine side chain is just a single hydrogen atom, while a tryptophan side chain is a large aromatic ring. It’s very tricky to get a single model to handle things with such huge size differences. The researchers used a “virtual node” strategy to solve this. It’s like placing a universal “placeholder” before building the structure, allowing the model to first learn what chemical properties and spatial shape are needed at that position, and then generating the specific atoms based on that information. This is a smart piece of engineering.

Of course, no matter how elegant a model is, performance is what counts. The researchers’ data show that UNAAGI performs better than the current best methods for handling ncAAs. More importantly, its predictions correlate well with real experimental data. This suggests it’s not just making things up but has actually captured some underlying physical and chemical principles.

For me, the most insightful part of this work is that it blurs the line between protein engineering and structure-based drug design. Essentially, both fields are solving the same problem: how to place the right set of atoms in a specific pocket of a protein to perform a particular function. What UNAAGI does is successfully apply the atom-based, 3D structure-based thinking from drug design to the task of building the protein itself.

This points to a future where designing new proteins might become more like how we design small-molecule drugs today—with precision down to every single atomic interaction.

📜Title: UNAAGI: Atom-Level Diffusion for Generating Non-Canonical Amino Acid Substitutions

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.10515v1

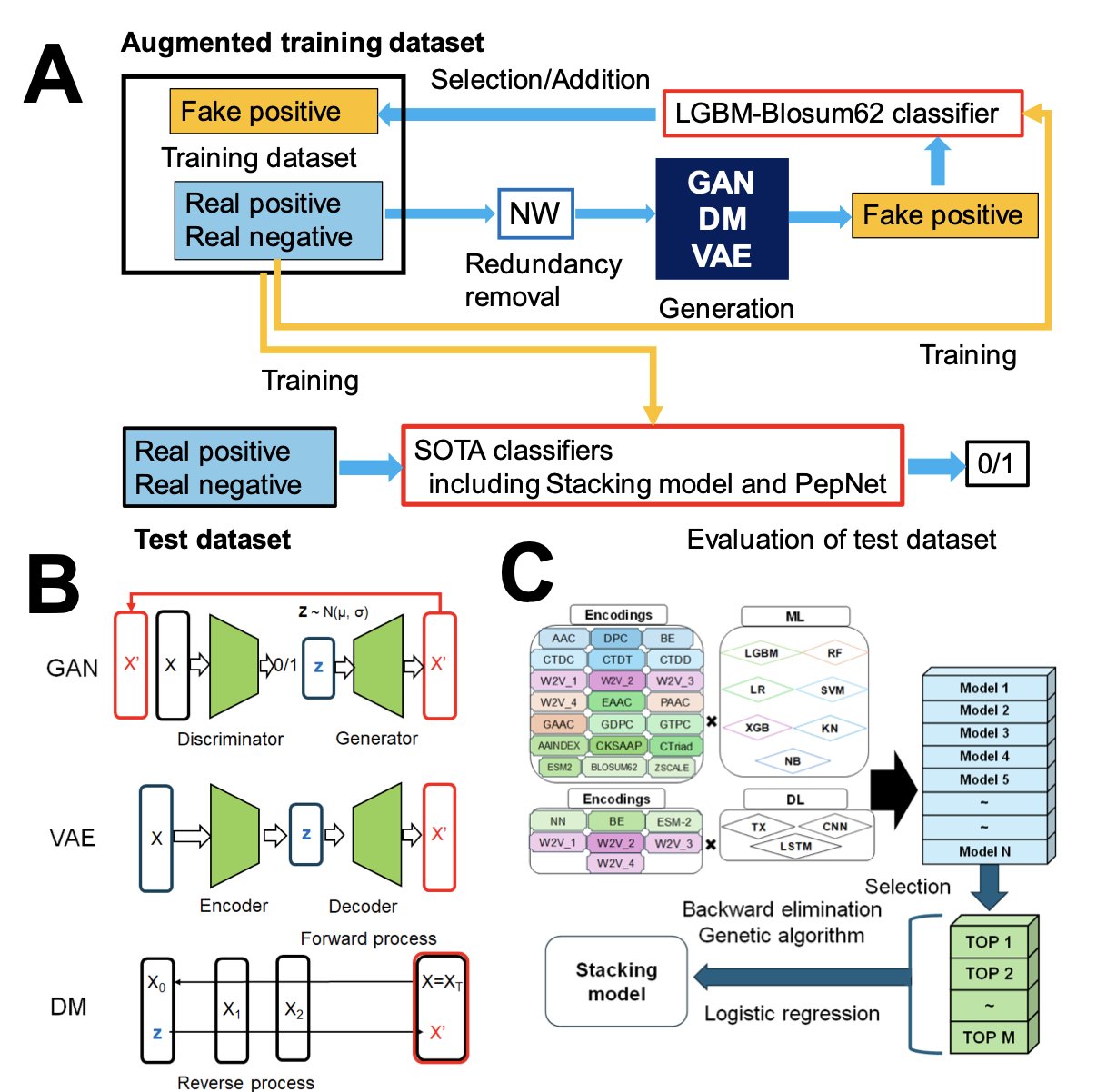

6. AI-Generated Data: A New Way to Predict Immunopeptides

In peptide drug discovery, we always run into an old problem: we have too little positive data. Without enough data, it’s hard for machine learning models to learn, and their predictive performance suffers.

The authors of this paper came up with a solution: if real data is insufficient, use Generative AI to create some.

Their framework is called GDA-Pred. They tested three popular types of generative models: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), diffusion models, and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). You can think of it as hiring three “apprentices” with different styles to imitate the work of a master (the known active peptides).

What was the result? GANs came out on top. The sequences they generated not only looked plausible but also had good diversity. This is critical for training a model because we don’t want the new data to be a simple copy-paste of the old data. We need it to fill in the gaps in the sequence space, making the model’s decision boundary smoother and more robust.

There’s a clever design choice here. The authors didn’t tune the model’s hyperparameters directly on the target datasets (IL-6 and IL-13 inducing peptides) because the datasets are too small, which could easily lead to overfitting. Instead, they first used a medium-sized dataset of anti-inflammatory peptides (AIPs) to “practice” and find the optimal settings for key parameters like sequence consistency and probability thresholds. This is like calibrating an instrument with a standard before using it to measure unknown samples; the results are more reliable.

Of course, claims need to be backed by solid testing. They used a rigorous, stratified 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate performance. To prevent artificially high scores from “related” sequences in the training and testing sets, they also performed clustering based on sequence similarity. This ensures the model is being tested on data that is truly “unseen.”

The results showed that models trained on data augmented by GDA had significantly better performance in predicting IL-6 and IL-13 inducing peptides, leaving traditional data augmentation methods like SMOTE and KDE behind.

This means that even with only a small amount of experimental data, it might be possible to train powerful predictive models. This is definitely good news for research on many niche targets or new peptide functions. It can help us more quickly screen promising candidates from vast sequence libraries and accelerate the early stages of drug discovery.

📜Title: GDA-Pred: Generative AI-Driven Data Augmentation for Improved Prediction of IL-6 and IL-13 Inducing Peptides

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.07.692883v1