Table of Contents

- This AI agent acts like a built-in bioinformatician, autonomously handling the entire NGS analysis workflow from raw data to biological insights.

- A new AI framework that breaks down the key physical forces in molecular binding as it happens, with remarkable efficiency.

- By combining AI structure prediction with evolutionary data, we can design entirely new gene-editing tools that are more active than their natural counterparts.

- Using sparse autoencoders, we can finally dissect the jumbled knowledge inside chemistry language models into understandable, controllable chemical concepts—turning the AI from a black box into a white box.

- ProteinEBM converts a diffusion model into a universal energy function for proteins. It not only surpasses Rosetta in structure scoring but also achieves better de novo folding than AlphaFold without using multiple sequence alignments (MSAs).

- ICFinder uses a protein language model to accurately identify ion channels and their key functional residues without relying on 3D structures, opening up a new path for drug discovery.

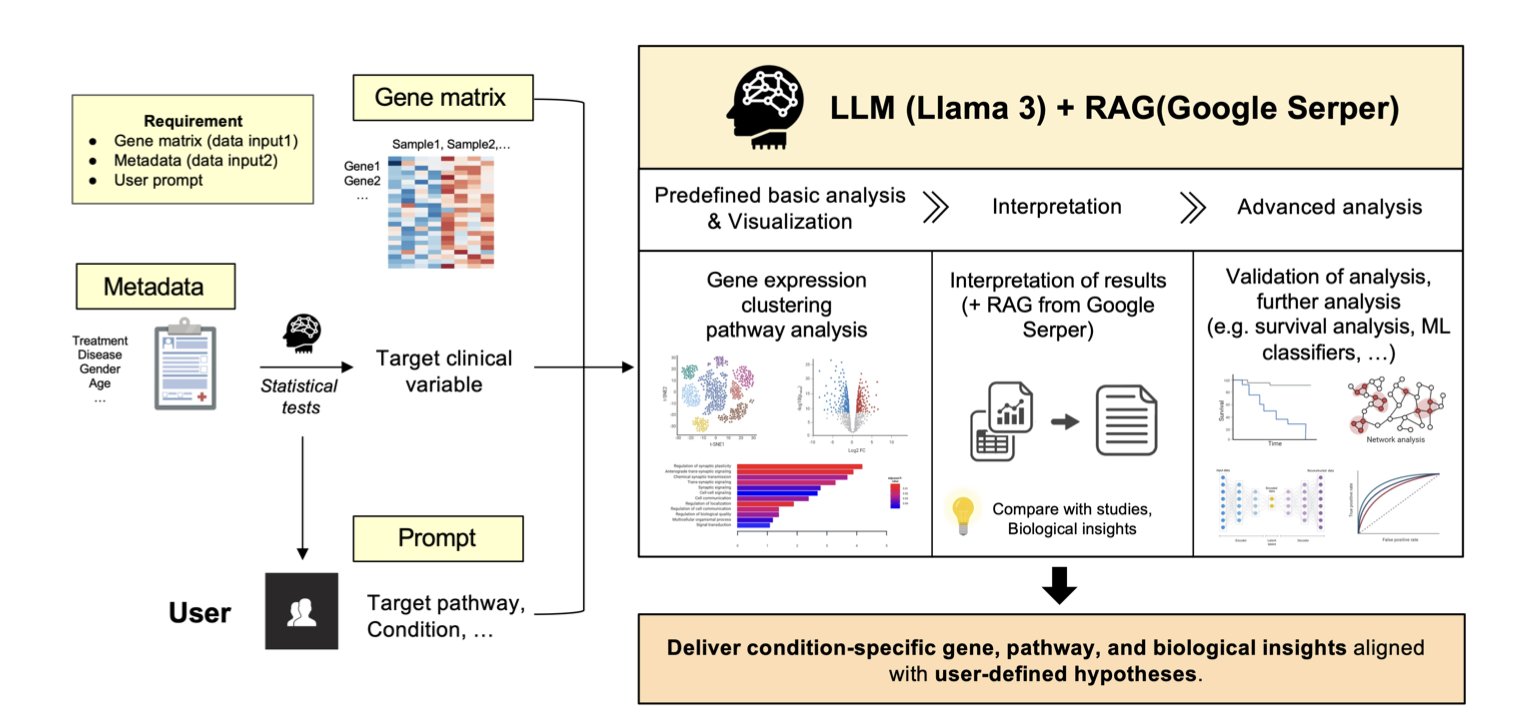

1. An AI Agent That Masters NGS Analysis, So You Don’t Have To

Anyone in biological research, especially drug development, knows the pain of dealing with Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data. You finish an experiment and get a huge gene expression matrix. What’s next? Usually, you have to find a professional bioinformatician, hand over your data and requirements, and then wait. This process is often a major bottleneck in drug discovery projects.

The tool proposed in this paper aims to break that bottleneck. The researchers developed an “Agentic AI” model to make bioinformatics analysis as simple as having a conversation.

Here’s how it works.

First, you feed it your data. This includes the gene expression matrix and relevant clinical information, like which samples were treated with a drug and which were controls. Then, you give it instructions in natural language, such as, “Help me compare the gene expression differences between the drug-treated group and the control group.”

Then the agent gets to work. It’s not just a simple script; it actually “plans” its own workflow. 1. It starts with some basic analysis. For example, it runs a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to see if your samples cluster clearly by group, which helps you judge data quality. 2. Then, it performs the core task. It automatically runs a differential expression analysis to find statistically significant up- or down-regulated genes and generates the familiar Volcano Plot. 3. Here’s the most important step: interpretation. A list of genes isn’t very useful on its own. The agent integrates a Large Language Model (LLM)—specifically, Llama 3-70B—with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technology. It takes the list of differential genes, automatically searches relevant scientific literature, and then explains which biological pathways these genes might be involved in and how they connect to your research. It doesn’t just list pathway names; it tries to weave the information into a logical story. For instance, it might tell you: “The most significantly upregulated gene, Gene A, is a key node in the MAPK pathway. Existing literature shows that inhibiting this pathway is an effective strategy for treating this type of cancer. This might explain why your drug works.”

This ability to automate the path from data to insight is enormously valuable for chemists or clinicians who aren’t bioinformatics experts.

If you want to dig deeper—say, build a predictive model from the gene expression data to see which patients will respond to treatment—the agent can help with that too. It will recommend suitable machine learning models, like survival analysis or classifiers, and directly generate executable Python code. You barely need to know how to program; just copy the code into your environment and run it. This significantly lowers the barrier to advanced data analysis.

So, will this replace professional bioinformaticians?

I don’t think so, at least not in the short term. It’s more like a highly capable junior analyst that can handle 80% of routine analysis tasks, freeing up professional analysts to focus on the 20% of problems that are most difficult.

For drug development, this means the cycle time from receiving sequencing data to forming a testable biological hypothesis is drastically reduced. Teams working on target discovery and validation can iterate on their ideas much faster.

The model still has room to improve. The researchers mentioned that future versions will support integrated analysis of multi-omics data (like proteomics and metabolomics) and will include drug response prediction. If they can pull that off, it will be more than just an analysis tool—it will be a true drug discovery engine.

📜Title: Development of an Agentic AI Model for NGS Downstream Analysis Targeting Researchers with Limited Biological Background

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.09964v1

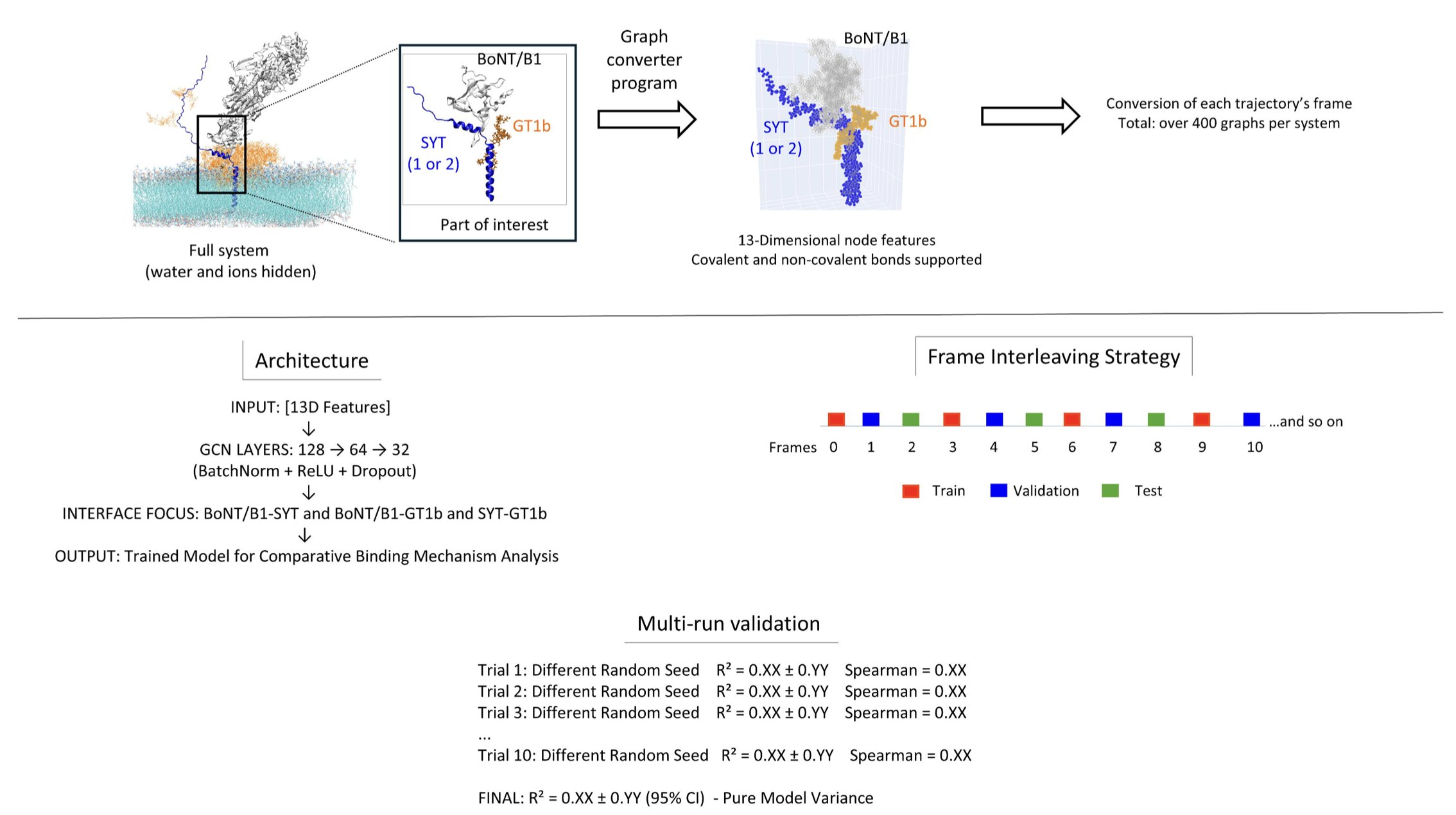

2. TPS: A New AI Tool to See Molecular Binding in Real Time

In drug development, we’re always asking a central question: How do two molecules recognize and bind to each other? Knowing the binding strength, or affinity, isn’t enough. We want to know the “story” of the binding process—which amino acid does what, and when. Traditional methods involve either looking at static X-ray crystal structures or running extensive, time-consuming molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, both of which are costly.

Researchers have now developed an AI framework called Temporal Perturbation Scanning (TPS) to tackle this problem.

Here is how it works. First, it uses a single molecular dynamics simulation to generate a “dynamic movie” of the binding process. Then, a Graph Neural Network learns all the atomic interactions in that movie.

Here’s the clever part: it systematically performs in silico mutagenesis on each amino acid residue during this dynamic process. It’s like going through the movie frame by frame and poking one of the actors to see how the plot changes. By observing these changes, TPS can tell you whether a specific amino acid residue is contributing through electrostatic attraction, hydrophobic interactions, or steric hindrance at the beginning, middle, and end of the binding event.

The value of this method lies in its efficiency and depth. Previously, to understand the role of 10 amino acids, you might have had to run dozens of separate, lengthy simulations. With TPS, you can extract the same detailed mechanistic information from just one simulation. This makes in-depth mechanistic studies accessible to labs without massive computational resources.

The researchers applied it to the interaction between neurotoxins and their receptors. The results were interesting. They found that two structurally similar botulinum neurotoxins (BoNT/B1) use completely different strategies to bind to two different synaptic vesicle proteins (SYT1 and SYT2). One uses “compensatory assembly,” where different parts flexibly complement each other to bind. The other uses “modular binding,” where each part works independently, like Lego bricks. Such detailed insights are critical for designing highly specific drugs.

Recognizing that not everyone can easily run MD simulations, the authors also offer a simplified version—TPS-Lite. It works directly with static structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Although it provides less information, it’s a very practical tool for quickly screening key residues at an interface or for educational purposes.

The framework is broadly applicable. The paper demonstrates its use in protein-protein and protein-lipid systems. This means TPS could become a powerful analytical tool for enzyme engineering, drug discovery, or membrane biology research.

The authors suggest that TPS transforms molecular recognition from an “observational science” into an “engineering discipline.” That’s not an exaggeration. When we can clearly map out every step of molecular binding, we can start to proactively design and control the process, not just observe and predict the outcome.

📜Title: Temporal Perturbation Scanning: AI-Driven Deconstruction of Universal Biomolecular Recognition Mechanisms

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.09.692808v1

💻Code: https://github.com/fodil13

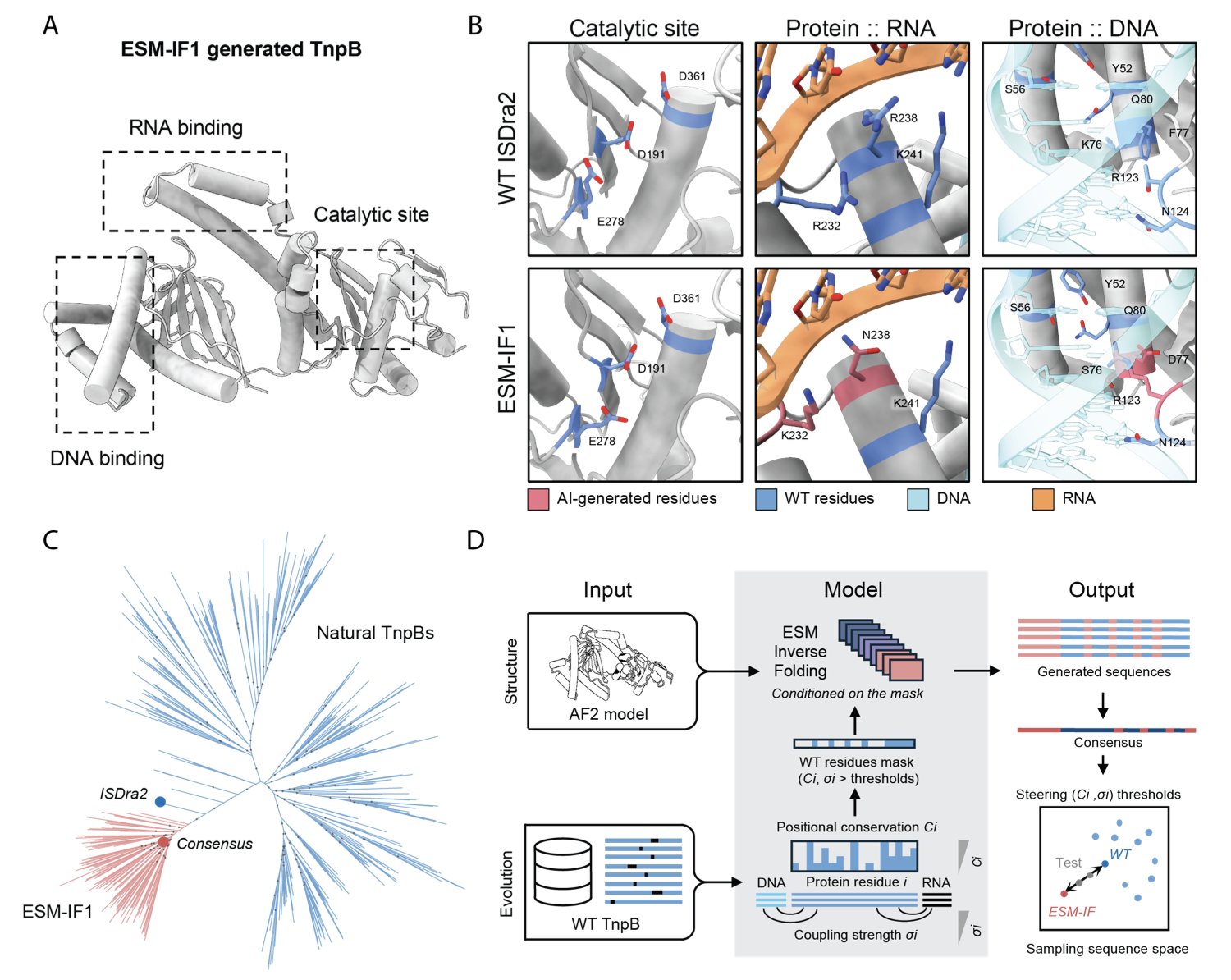

3. AI + Evolution: Designing Gene-Editing Tools That Surpass Nature

In protein engineering, the dream has always been to design a completely new protein from scratch to perform a specific task, like designing a machine part. But proteins are too complex; the combinatorial space of amino acid sequences is astronomical. For years, we’ve mostly been tinkerers, making small modifications to proteins that already exist in nature. Now, that’s starting to change.

This research focuses on TnpB, a class of RNA-guided nucleases. You can think of them as smaller, more ancient ancestors of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Their small size is an advantage, making them easier to deliver into cells. The researchers wanted to do more than just tinker—they wanted to redesign TnpB from the ground up.

Their method cleverly combines two powerful forces: structure and evolution.

First, they used an AI-driven technique called “inverse protein folding.” This is like having a perfect 3D model of a protein structure and asking a computer to figure out which amino acid sequences could build it. This process can generate a massive number of sequences never seen in nature.

But there’s a big problem: the vast majority of AI-generated sequences are “dead.” They either fail to fold or fold into an inactive shape. Many of a protein’s critical functional sites are like the core gears in a machine—change them, and the whole thing breaks.

This is where the second force, evolution, comes in. The researchers analyzed thousands of natural TnpB variants from its long evolutionary history. They found that some amino acid positions almost never change; these are the core pillars that maintain structure and function. Other positions are closely involved in binding to RNA or DNA.

So, they developed a “masking strategy.” During AI sequence design, they “locked” these evolutionarily conserved and functionally critical positions, preventing the AI from changing them. In other, non-essential regions, they gave the AI free rein to be creative.

How well did this combined approach work? Surprisingly well. They designed and tested a large number of new TnpB variants and found that 24% were active. Even more impressive, 8% of the new enzymes were more active than the natural, wild-type TnpB. This was confirmed in bacteria, plants, and even human cells.

To understand why these new designs worked, they used Cryo-EM to determine the 3D structure of one of the most different yet highly active variants. The result confirmed that the AI’s design had folded precisely into the intended structure. The structural analysis also revealed new interactions that stabilize RNA/DNA binding and even captured a previously unobserved key moment of target DNA engagement. This not only proved the design was successful but also deepened our understanding of how TnpB works.

This “structure-guided, evolution-constrained” strategy opens a new path for protein design. It’s like pairing a highly creative but sometimes undisciplined designer (the AI) with an experienced chief engineer (the evolutionary data) who knows the fundamental constraints. This approach isn’t limited to TnpB; it could theoretically be applied to the design of other multi-domain proteins, providing a powerful way to create new biomolecular tools.

📜Title: Structure and evolution-guided design of minimal RNA-guided nucleases

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.08.692503v1

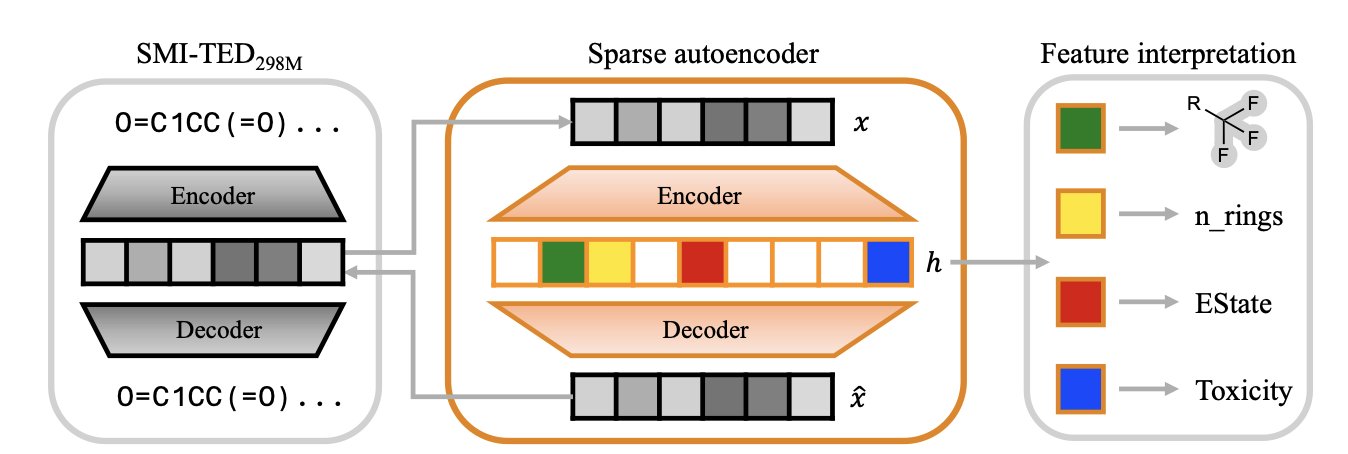

4. Decoding the AI Brain: SAEs Make Chemistry Language Models Interpretable

When we use large language models in drug discovery, we run into a persistent problem: they are black boxes. A model might tell you one molecule is active and another is toxic, but if you ask why, it can’t explain its reasoning. You don’t know if it learned real chemical principles or just memorized some coincidental statistical patterns. In a field like drug discovery, where lives are at stake, we can’t accept a tool that gives answers without explanations.

A new paper has handed us a scalpel—or maybe a “brain microscope”—called Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs). This tool helps us pry open the black box of Chemistry Language Models (CLMs) and see how they actually think.

How SAEs work is simple.

Imagine the model’s internal “understanding” of a molecule is like a mixed fruit juice. You know it tastes sweet, but you can’t tell what specific fruits are in it. An SAE’s job is to separate this juice back into pure strawberry, banana, and apple. In a chemistry model, these “pure ingredients” are individual chemical concepts, like a benzene ring, a sulfonamide group, or the property of “high lipophilicity.”

The researchers fed the internal representations of a top chemistry model, SMI-TED, into an SAE. The SAE is designed to be “sparse,” meaning that when analyzing any given molecule, it can only activate a very small number of its feature detectors. This forces each detector to become highly specialized, focusing on identifying one specific, meaningful chemical concept.

The results are compelling.

The paper’s figures show that a specific SAE feature activates only when molecules containing a certain functional group (like a sulfonamide) are input. It’s like finding a single neuron in the model’s “brain” that is dedicated to recognizing “sulfonamides.”

What’s more, the feature detectors built by the SAE are “purer” than the model’s original, individual neurons. A single neuron in the model might respond to both a benzene ring and a carboxyl group—a phenomenon called “polysemanticity.” The SAE overcomes this by combining multiple “impure” neurons to create one “pure” feature that responds only to the benzene ring. Because of this, it can even capture rare chemical motifs that appear infrequently in the dataset but are critical for drug-likeness.

From “Reading” to “Controlling”

The highlight of this work is the “feature steering” experiment. This turns the SAE from an observation tool into a surgical one.

Researchers can lock onto the feature for a chemical group and instruct the model: “Generate a similar molecule, but remove this group.” Or, “Increase this molecule’s water solubility.” The model can actually perform these targeted edits while keeping the molecule’s basic scaffold valid. This demonstrates a direct, causal link between these features and chemical concepts, not just a simple correlation. For medicinal chemists, this means we might one day be able to make precise refinements to AI-designed molecules, instead of just having the model blindly generate a huge batch of candidates for us to screen.

This technology is still in its early stages. Interpreting what each feature means chemically still requires a lot of manual work. And it has only been validated on one model; whether it can be generalized to other models and larger chemical spaces is an open question.

Still, this is a solid step forward for AI-assisted drug discovery. It brings us closer to the goal of truly understanding and trusting our AI partners. We finally have a way to conduct “cognitive neuroscience” on an AI.

📜Title: Unveiling Latent Knowledge in Chemistry Language Models through Sparse Autoencoders

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.08077

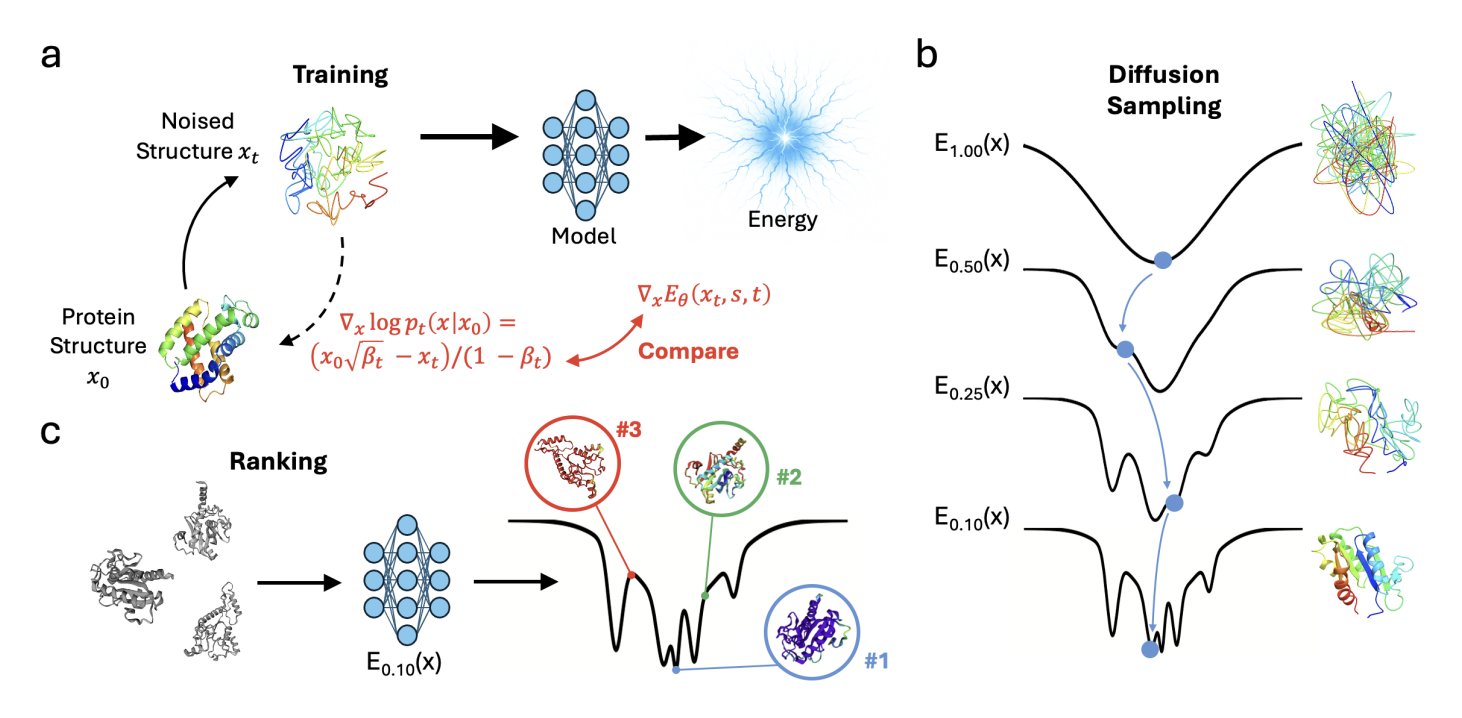

5. ProteinEBM: Defining Energy with Diffusion Models to Beat AlphaFold Without MSA

Over the past few years, we’ve watched AlphaFold change structural biology. But one of its core dependencies is Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSA), which is like having an open-book test—it infers structure from the evolutionary information of countless related sequences. If a protein family is new or small with insufficient sequence data, AlphaFold’s power diminishes. So, the field has been searching for a method that is closer to “first principles,” one that predicts structure directly from physicochemical rules without relying on evolutionary information. A model called ProteinEBM appears to be a big step in that direction.

The idea is clever. We know diffusion models generate new data by repeatedly adding noise and then learning how to remove it. The researchers behind ProteinEBM realized that this “denoising” process itself contains energy information. The closer a structure is to its natural conformation, the lower it sits in the energy landscape, and the more clearly the model knows how to “fix” it. They define the “force” of this denoising process as the gradient of the energy. With this, the entire diffusion model becomes an energy function, or a statistical potential.

What is this energy function good for? First, for “scoring” protein structures. Give it a conformation, and it can tell you how “plausible” it is. The researchers tested it on the Rosetta decoy set, which contains a mix of correct and incorrect protein structures. The Spearman correlation between ProteinEBM’s energy score and the true structural similarity (TM-score) was 0.815. For comparison, the classic Rosetta energy function scored only 0.757. ProteinEBM is also 10 times faster because it doesn’t need to perform time-consuming side-chain packing.

The real highlight is de novo folding. Without using any MSA, they used a Langevin annealing algorithm to search the energy landscape defined by ProteinEBM, followed by a final refinement step with AlphaFold. On a set of difficult monomeric protein targets, the average TM-score reached 0.620. This number surpasses AlphaFold2 run without MSA (0.561, with 10,000 random seeds) and even AlphaFold3 (0.512, with 15,000 tries). This shows that the energy landscape provided by ProteinEBM can effectively guide the structural search in the right direction, making up for AlphaFold’s weakness when information is scarce.

The model can also do more biophysically oriented tasks. For instance, it can predict changes in protein stability after mutation (∆∆G), with results showing a correlation of 0.554 with experimental data, comparable to some supervised models. It can also reproduce the folding funnels of small proteins, proving it’s not just fitting static structures but has learned something about the energy principles that drive protein folding.

I think the core advantage of this model is its separation of scoring and sampling. Models like AlphaFold generate a structure in a single, end-to-end process. ProteinEBM, on the other hand, provides an energy field. This means that during inference, we can invest as much computational power as we want, using more sophisticated sampling algorithms to explore this field and theoretically find better structures. It’s like being given a treasure map (the energy landscape). You can choose to explore it with a regular jeep (fast sampling) or a professional expedition team (slower but more thorough sampling). This flexibility is extremely valuable for designing entirely new proteins (de novo design) that don’t exist in nature.

📜Title: Protein Diffusion Models as Statistical Potentials

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.09.693073v1

💻Code: https://github.com/jproney/ProteinEBM

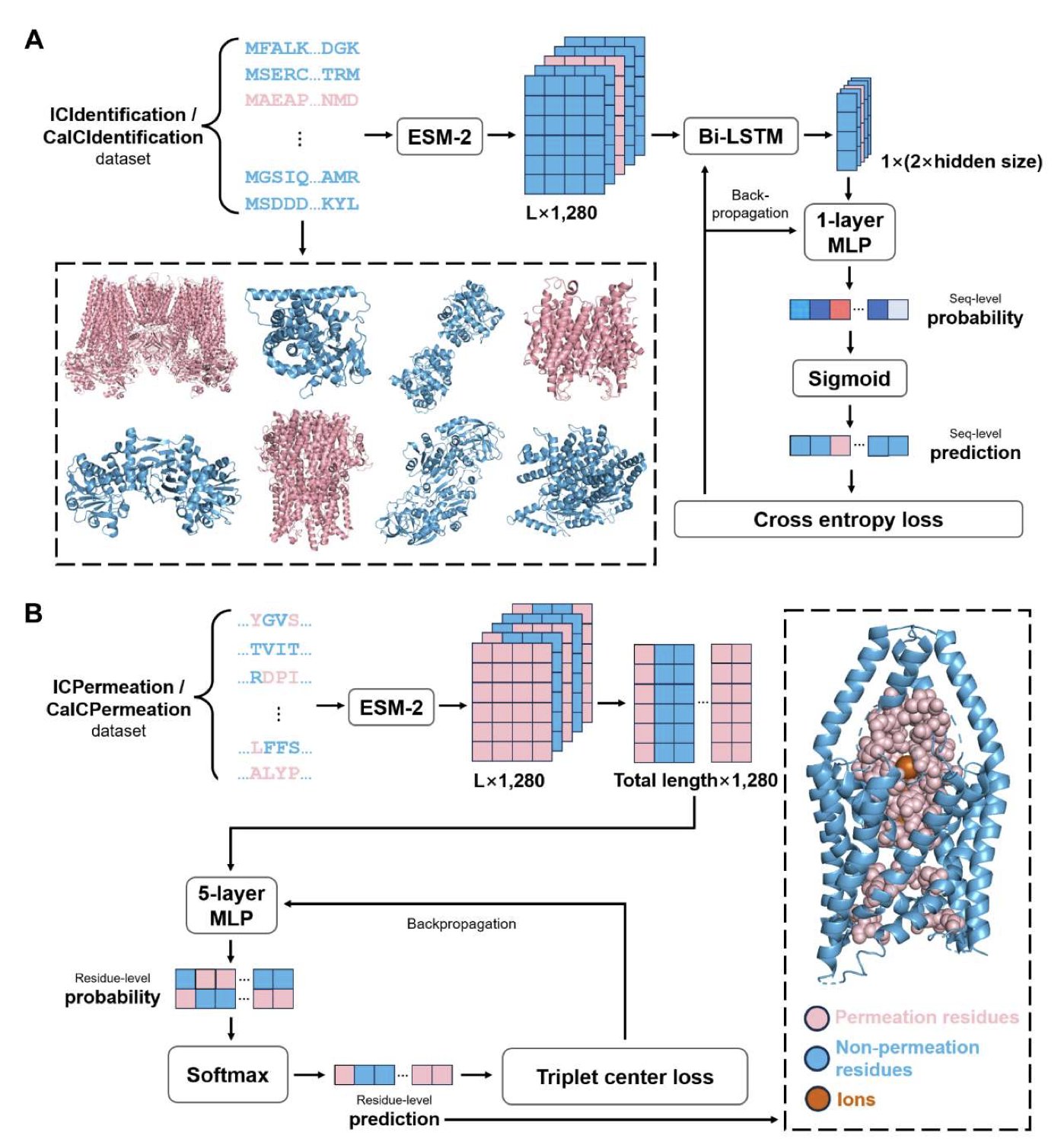

6. AI Pinpoints Ion Channels, Accelerating New Drug Target Discovery

Ion channels are a well-known “gold mine” for drug targets in our industry, with many blockbuster drugs acting on them. But they are also notoriously difficult to work with. A central challenge is that even after we have a protein’s sequence, or even a 3D structure predicted by AlphaFold, it’s hard to tell which amino acid residues form the “pore” that allows ions to pass through. Identifying these key residues is essential for understanding channel function and designing drugs.

A new paper introduces a computational framework called ICFinder, which aims to solve this problem with a new approach.

Here’s how it works: Instead of starting with complex 3D structures, ICFinder goes back to the most fundamental information—the protein sequence. It treats protein sequences as a “language” and uses a powerful Protein Language Model, specifically ESM-2, to “read” them.

ESM-2 was pre-trained on massive amounts of protein sequences and has learned the grammar and semantics of protein language. This means it understands the meaning of an amino acid in its specific sequence context. ICFinder is then fine-tuned on this foundation to do two things: first, determine if a given sequence is an ion channel, and second, if it is, identify which residues in the sequence are responsible for ion permeation.

There is a big technical hurdle here: data imbalance. In any ion channel protein, the residues that actually form the pore are a tiny minority; the vast majority are “non-pore” residues. If used for training directly, a model could easily learn to cheat by predicting every residue as “non-pore” and still achieve high accuracy, making it useless.

The researchers used a smart method to overcome this: contrastive learning and triplet center loss. You can think of it as increasing the training difficulty for the model. Instead of just learning to distinguish “yes” from “no,” the model is given a “pore residue,” a “non-pore residue,” and a “distractor” that looks similar to a pore residue but isn’t one. This forces the model to learn the most subtle yet critical features that truly define a pore residue.

How did it perform? ICFinder’s performance is excellent. Across multiple test sets, its performance metric (Matthews correlation coefficient) improved by as much as 171% over the best existing methods. This represents a huge leap in prediction reliability.

The value of this tool is twofold:

First, it perfectly complements structure prediction tools like AlphaFold3. AlphaFold gives us a static 3D structural model, like a building’s blueprint. ICFinder can then take that blueprint and circle in red the “load-bearing walls” and “windows”—the functionally critical residues. By combining the two, we can understand a new target much faster.

Second, it eliminates the dependency on experimental structures. This means we can apply it to vast numbers of proteins for which we only have sequence information and unknown functions. The researchers have already used it to scan the UniRef50 database and have made their predictions for potential ion channels available on a public web server. This provides a massive pool of candidates for finding new drug targets.

The researchers also performed an interpretability analysis. They could ask the model, “Why do you think this residue is part of the pore?” The model would then highlight the sequence features that were most important for its decision. This not only increases our confidence in its predictions but may also inspire new insights into how these channels work.

ICFinder provides a powerful, easy-to-use new tool. By leveraging a large language model to mine functional information from sequences and precisely locate the core regions of ion channels, it will directly accelerate the process of discovering and validating new drug targets.

📜Title: ICFinder: Ion Channel Identification and Ion Permeation Residue Prediction Using Protein Language Models

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.09.693328v1