Table of Contents

- MolSculpt uses a chemistry-aware 1D model to guide a 3D diffusion model, generating geometrically precise 3D molecules directly from a chemical formula.

- Researchers developed a computational strategy (CADAbRe) to directly generate highly stable and diverse antibody libraries with drug-like properties comparable to clinical-stage molecules.

- By allowing protein side chains to move continuously during docking, DRGSCROLL uses a genetic algorithm to find more realistic drug binding modes that traditional rigid docking methods miss.

- The workflow of using AlphaFold2 refolding to validate new protein designs has serious flaws, as evolutionary information can mask the true quality of a design.

- For truly novel drug targets, physics-based molecular docking is more trustworthy than AI co-folding models that rely on training data.

- For machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) to be truly generalizable, long-range interaction models are necessary, but current methods still struggle with complex systems like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

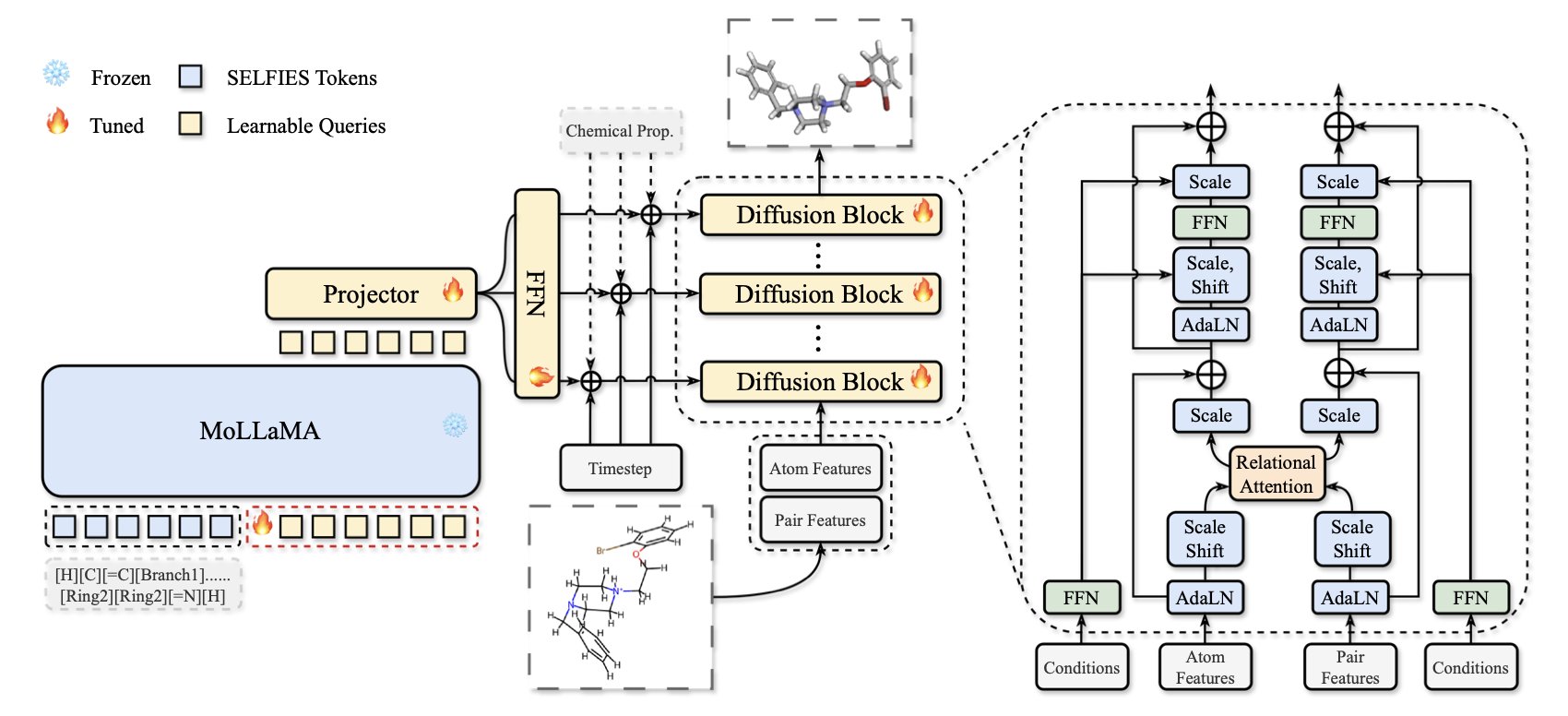

1. MolSculpt: AI Sculpts Precise 3D Molecular Structures from Chemical Formulas

In drug discovery, we often start with a one-dimensional chemical formula, like a SMILES string. This is like getting a list of molecular parts. The real challenge is assembling these parts (atoms) in three-dimensional space to form a stable and biologically active structure. Past methods often struggled, producing molecules that were either chemically nonsensical or had inaccurate 3D structures.

MolSculpt offers a solution. Its name, “molecular sculpting,” is fitting because it truly refines a molecule with precision.

Here’s how it works: the researchers split the task between two “experts.”

The first expert is a pre-trained 1D molecular foundation model that understands chemical rules. You can think of it as a senior chemist who has seen vast numbers of chemical structures and knows the rules of atomic connections and bonding inside out. Crucially, this model is “frozen”—it is not modified during MolSculpt’s training. We simply consult it for advice, rather than retraining it, which saves a lot of computing power.

The second expert is a 3D diffusion model. It’s a “sculptor” skilled at arranging atoms in 3D space. It starts with a random cloud of atoms and progressively adjusts their positions until a clear molecular structure emerges. The problem is, this sculptor doesn’t know chemistry on its own. Without guidance, it might create a bizarre, unstable structure.

MolSculpt’s core innovation is building a communication bridge that lets the chemist guide the sculptor. This bridge consists of two parts: learnable queries and a projector.

The process unfolds like this: at each step, the 3D sculptor asks the 1D chemist questions via the “learnable queries.” These questions are specific, like: “Based on this SMILES formula, what should the chemical environment around this carbon atom be?” or “What should the relationship between this nitrogen atom and that oxygen atom be?”

After the 1D chemist provides its expert answers, the projector translates this chemical knowledge into specific 3D coordinates and geometric constraints, telling the sculptor what to do next. This way, every step the sculptor takes is guided by the chemist, ensuring the final product is not only well-formed but also obeys all chemical principles.

So, how well does it work? The test results on two standard datasets, GEOM-DRUGS and QM9, speak for themselves. The molecules generated by MolSculpt achieved top-tier performance in chemical validity and stability.

More importantly, its ability to reconstruct local geometry—like bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles—is excellent. In drug design, a molecule’s conformation, especially a critical dihedral angle, can completely change its shape if it’s off by even a small amount. It might then fail to fit into the target protein’s active site. MolSculpt’s ability to accurately restore these details means its generated conformations are closer to the real-world dominant conformations, which is hugely valuable for virtual screening and subsequent lab validation.

The work also explores architectural details, like the optimal number of queries to use. This shows the researchers are seeking a balance: extracting enough information from the 1D model to guide 3D generation without introducing noise from information overload.

MolSculpt doesn’t just stick two models together; it designs an elegant system for them to work together, letting each play to its strengths. It gives us a powerful and efficient tool for generating high-quality, high-precision 3D molecules from scratch.

📜Title: MolSculpt: Sculpting 3D Molecular Geometries from Chemical Syntax

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.10991v1

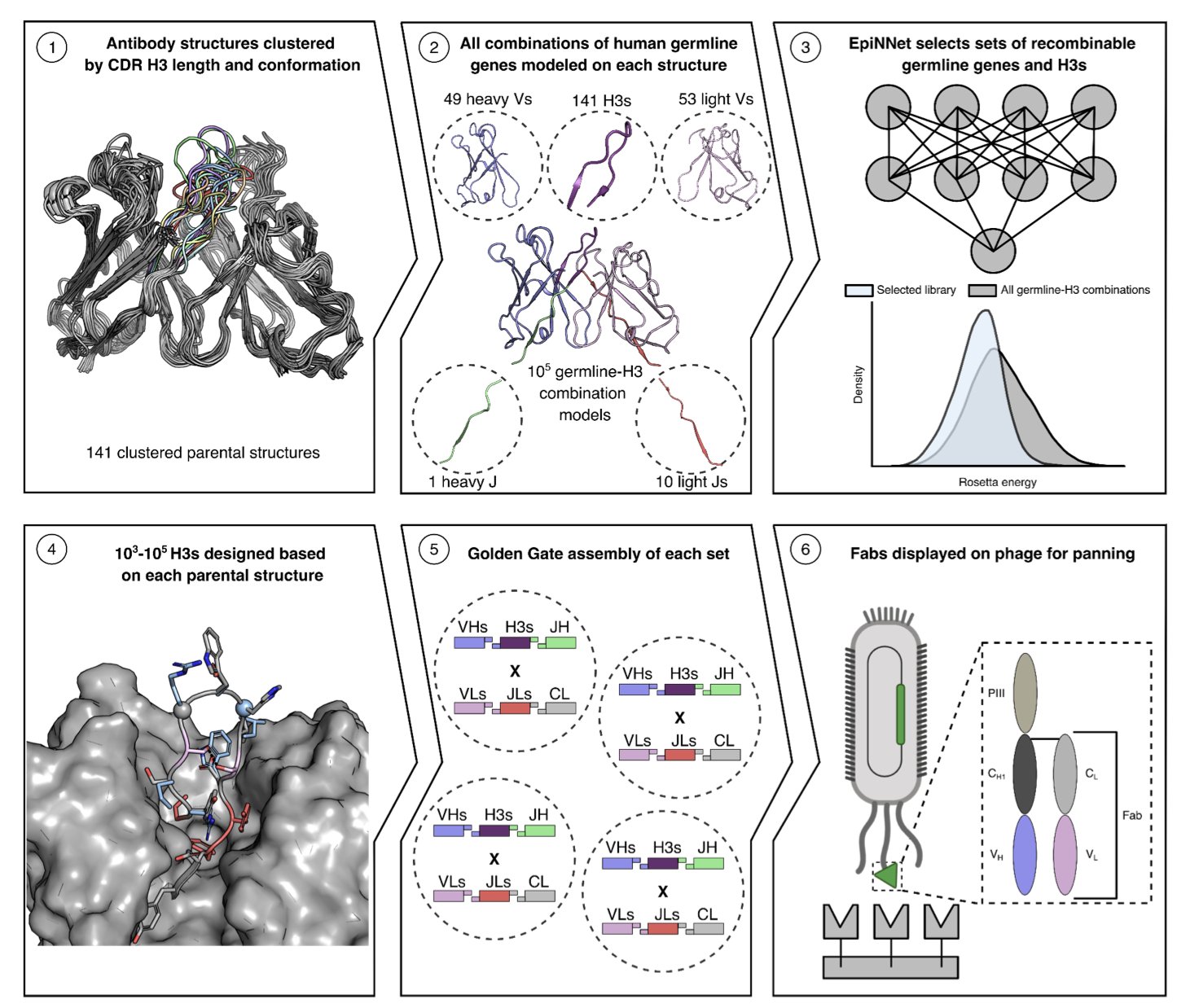

2. Structure-Guided Antibody Design: The CADAbRe Strategy

Anyone working on antibody drugs knows how hard it is to build a good antibody library. Traditional methods either rely on animal immunization, which is slow and unpredictable, or on synthetic or semi-synthetic libraries, which often suffer from poor stability and limited effective diversity. If an antibody’s framework is unstable and prone to aggregation, it becomes a nightmare to develop into a drug, even if its Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs) can bind the target.

The CADAbRe strategy, proposed in this preprint, aims to solve this problem from the ground up. Instead of patching up existing, potentially flawed antibody scaffolds, it uses computation to design an ideal antibody library from first principles.

Here’s how it works:

First, it tackles the stability of the antibody framework. Antibodies are formed by pairing heavy- and light-chain variable regions (V-genes). Instead of random combinations, the researchers used Rosetta energy calculation software to systematically evaluate the interface binding energy of all possible human V-gene pairs. They selected only the pairs calculated to be most stable and least likely to dissociate to serve as the library’s scaffolds. This is like building a house on an incredibly solid foundation to ensure the entire structure is sound.

Next, they addressed the most critical and difficult part: the CDR H3 loop. The CDR H3 is central to target recognition, and its sequence and structural diversity directly determine how many antigens the library can recognize. But designing the H3 loop is extremely challenging, as long or poorly structured H3 loops are a primary cause of antibody aggregation. Here, the authors used a machine learning model to design H3 sequences that possess both structural diversity and stability. This model can generate H3 loops of various lengths and conformations while avoiding structures known to cause problems.

So, how good is the resulting library?

The researchers synthesized over 500 million unique antibodies and validated them using phage display. They chose two representative targets: the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 and the spike protein of the rare Lujo virus.

The experimental results are solid. They successfully identified multiple antibodies with high, nanomolar (nM) affinity for the targets. More importantly, these antibodies showed excellent “developability” metrics. For instance, their performance in thermal stability, solubility, and non-specific binding was comparable to that of therapeutic antibodies already in clinical trials.

This means we can potentially obtain a batch of high-quality lead molecules directly from computational design, skipping animal immunization and the extensive work needed later to optimize stability.

What does this mean for drug developers?

The CADAbRe approach represents a shift from “screening” to “design.” It’s not about finding a needle in a haystack; it’s about first drawing a blueprint for the ideal “needle” and then building it.

The platform is programmable. We can adjust the CDR design based on the structural information of a specific target, creating biased libraries tailored for a certain class of targets, like GPCRs or ion channels.

It also creates a “design-test-learn” feedback loop. Data from each screening round can be fed back into the original design algorithm, making the next generation of antibody libraries more precise and efficient. This greatly speeds up the antibody discovery cycle and reduces reliance on animal experiments. For drug development, any technology that shortens timelines and lowers the risk of failure is extremely valuable.

📜Title: Structure-based design of antibody repertoires with drug-like properties

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.10.693474v1

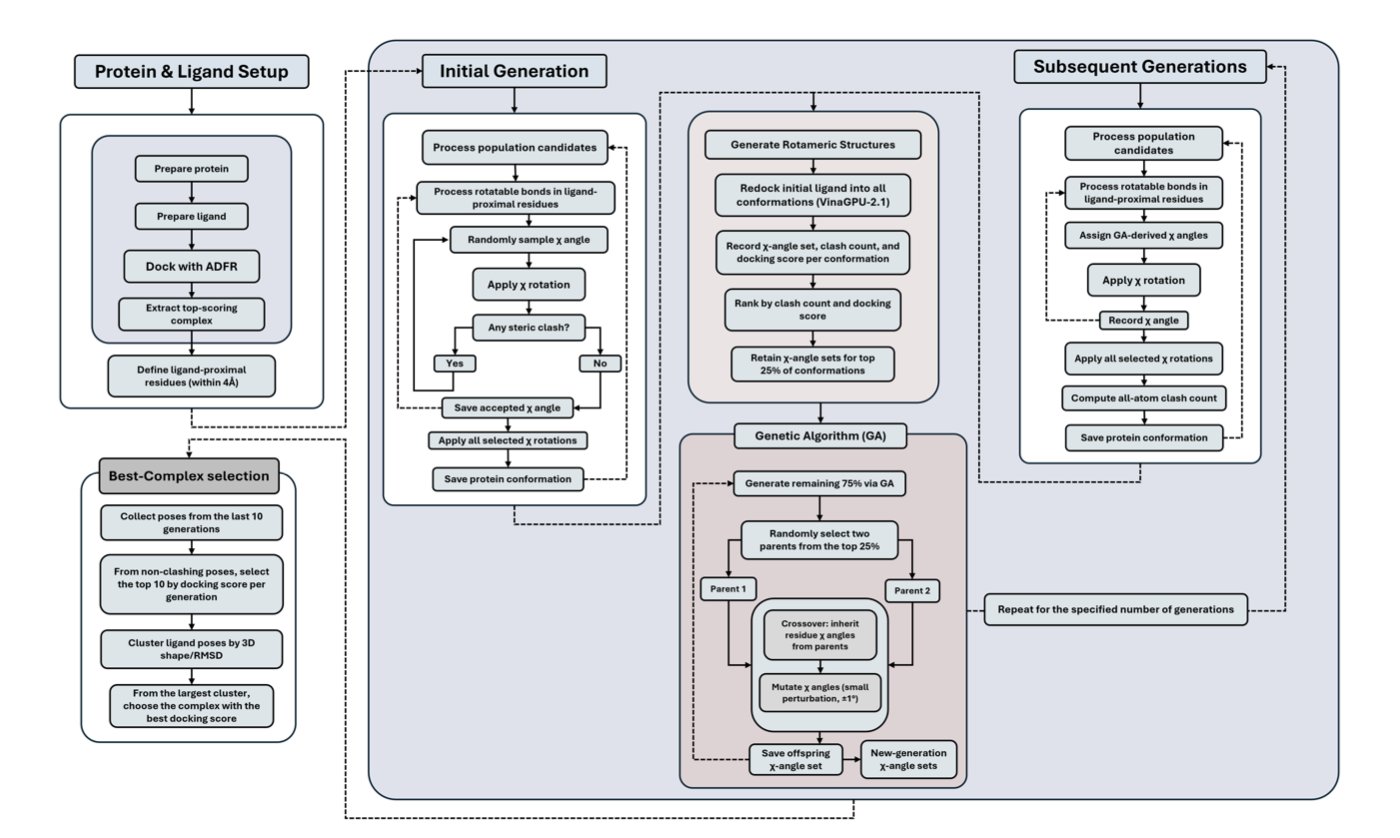

3. DRGSCROLL: A Genetic Algorithm for Fully Flexible Side-Chain Docking

Anyone who does molecular docking knows we’ve long made a huge compromise. To make computations feasible, we have to assume the protein target is a rigid block of stone. But in reality, proteins are flexible. The amino acid side chains in the binding pocket, in particular, can twist and turn to make room for a small molecule. This process is called “induced fit.” If we ignore this, many molecules that should bind well might be written off in a simulation due to a minor spatial clash.

DRGSCROLL aims to solve this problem head-on. Its core idea is simple: stop freezing the side chains and let them move.

How does it do it?

The researchers used a Genetic Algorithm. You can think of this process as a sophisticated evolutionary system. The system’s population includes not just the various poses of the small molecule (ligand) but also the torsion angles (χ angles) of all the side chains in the protein’s pocket.

The algorithm has two goals:

1. Find the lowest-energy binding state, meaning the tightest bind.

2. Avoid any unreasonable atomic collisions (steric clashes).

The genetic algorithm simultaneously optimizes both the ligand’s pose and all the side chain angles. It continuously generates new combinations, eliminates “inferior” conformations with high energy or clashes, and preserves and propagates “superior” ones with low energy and reasonable geometries. Through repeated iterations, it can efficiently search a massive conformational space to find the global optimal binding mode.

How well does it actually perform?

Let’s look at the data. The researchers benchmarked it against several industry-standard software tools, including Vina, Glide, and IFD (Induced Fit Docking), on the PDBbind dataset. The results showed that the conformations found by DRGSCROLL had significantly fewer atomic clashes and better docking scores. This confirms that it can indeed find more stable and realistic binding modes that require subtle side-chain adjustments.

Next came the more critical real-world test: virtual screening. This is the most common use case in drug discovery, where you try to pick out the true active “hits” from thousands of molecules. The researchers used DRGSCROLL to distinguish active compounds from decoys for two popular targets, RET kinase and PARP1.

The results were impressive. DRGSCROLL outperformed Vina GPU 2.1 across metrics like AUC, F1 score, and precision. This means it’s better at telling real compounds from fakes, helping us focus precious lab resources on the most promising molecules.

Is it practical to use?

Flexibility and computational cost are on a seesaw. The clever part of DRGSCROLL is that it’s optimized for GPUs. This allows it to handle full side-chain flexibility while maintaining an acceptable speed, making it feasible for at least medium-throughput virtual screening projects.

Of course, it isn’t perfect. It currently only considers side-chain flexibility; the protein backbone is still fixed, and water molecules are not explicitly considered. Still, this is a solid step toward “fully dynamic docking.” For targets where we know side-chain movement is critical for binding, DRGSCROLL provides a powerful new tool.

📜Title: DRGSCROLL: Achieving Full Side-Chain Flexibility in Docking Simulations through a Genetic Algorithm Framework

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.04.692419v1

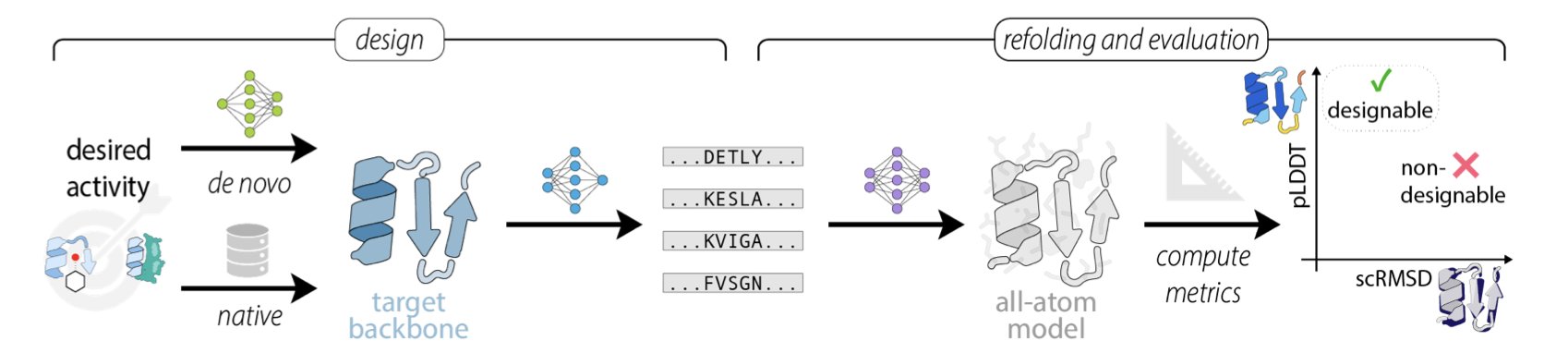

4. Validating New Proteins with AlphaFold2? Be Careful, There’s a Pitfall.

You’ve worked hard to design a completely new protein sequence. How do you know if it will fold correctly into your desired structure?

For the past few years, the standard answer has been: run it through AlphaFold2 and see how closely the predicted structure matches your design target. We call this process “refolding.” A high pLDDT score and a low scRMSD value seemed like a sure sign of success.

But a recent preprint pours some cold water on that idea. The researchers found that this routine workflow might be systematically misleading us.

Where’s the problem? It’s mainly the evolutionary information, the Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA). AlphaFold2 was trained on massive families of natural protein sequences. When you give it a sequence that’s somewhat similar to a natural protein and provide an MSA, it acts like a student taking an open-book test. It just pulls the answer from its memory banks instead of actually reasoning out how the sequence should fold from scratch.

This works great for predicting the structures of natural proteins. But for designers trying to create proteins that don’t exist on Earth, it’s a huge problem. The model might just be recognizing the “flavor” of a natural protein in your design and giving you a seemingly perfect result. This doesn’t prove your design itself is successful.

The researchers’ experimental data clearly shows this. As soon as an MSA is used, AlphaFold2’s ability to distinguish good designs from bad ones drops significantly. The pLDDT score (AlphaFold2’s confidence metric) gets artificially inflated because the model found something familiar, not because your sequence itself contains stable structural information.

Another key metric, scRMSD (side-chain root-mean-square deviation), is also unreliable. For proteins with flexible regions or random coils, this value can become inexplicably high, making you think your design failed. It’s like trying to measure a soft noodle with a rigid ruler—you can’t get an accurate measurement and then blame the noodle. Fortunately, the authors proposed a simple realignment and calibration method that can partially correct this issue.

So, what should we do now?

The subtext of this paper is this: when evaluating brand new, de novo designs, don’t put too much faith in AlphaFold2 running in MSA mode. Try the single-sequence mode instead. While the predicted results might not look as “stunning,” they are likely more “honest.” This mode better reflects the structural information contained within the sequence itself, rather than an answer memorized from a database.

This doesn’t mean AlphaFold2 is useless. It remains a valuable tool. But this work reminds us that every tool has its proper use cases and limitations. As front-line researchers, we must be like skilled craftspeople, knowing when a hammer is for driving a nail and when it’s likely to smash our thumb. Understanding these limits will help us move forward more steadily on the path of creating new molecules.

📜Title: Limitations of the refolding pipeline for de novo protein design

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.09.693122v1

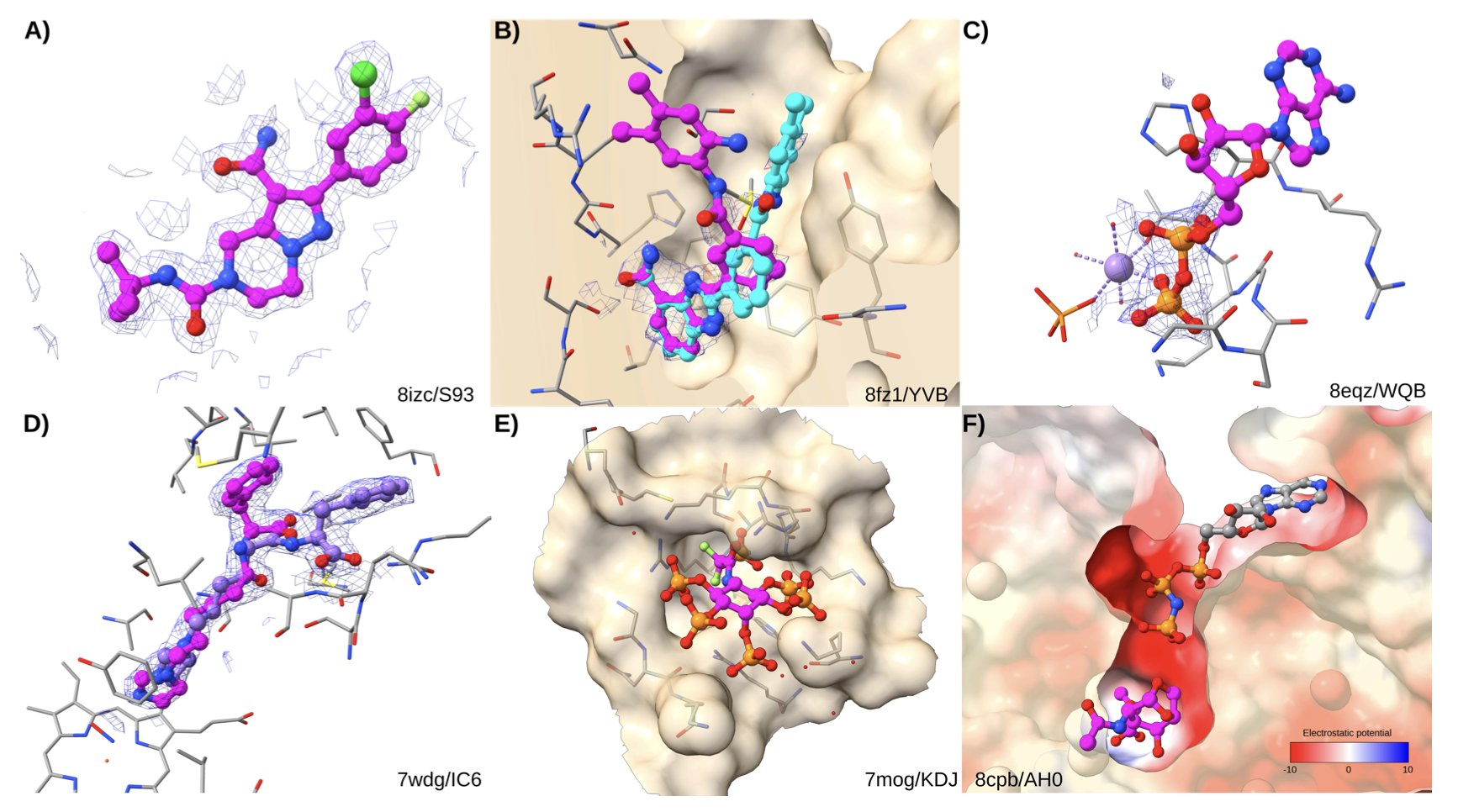

5. AI Drug Discovery: Co-folding vs. Docking—Which is More Reliable?

AI is a hot topic in drug discovery, and with the arrival of AlphaFold, many felt we were on the verge of predicting everything. But when AI models move from predicting protein structures to predicting how small molecules bind to them, things get more complicated. This new study puts AI co-folding models (like AlphaFold 3) and classic molecular docking methods in the same ring for a head-to-head comparison. The results are interesting and serve as a reality check for the field.

There’s a common perception that AI can do anything. But this research reveals an “Achilles’ heel” of AI co-folding models: their heavy reliance on training data. If a protein-ligand complex is very similar to a structure the model has “seen” in the PDB database, its prediction is highly accurate. Through logistic regression analysis, the authors found that similarity to the training set is the strongest predictor of co-folding success. This is like a student who only memorizes a question bank—they can ace questions they’ve seen before but are helpless when faced with a completely new problem type. In drug development, we are most interested in new targets and new chemical scaffolds, which is precisely where AI co-folding models are weak.

In contrast, traditional docking methods, while “old-school,” are more robust. They don’t rely on “memory” but on physicochemical principles—like van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions—to calculate the best pose and binding energy of a ligand in a pocket. Their success is more related to the ligand’s physical properties, such as whether it’s too flexible (too many rotatable bonds) or if the binding pocket is buried too deep. The study shows that docking software using more thorough sampling algorithms and better scoring functions (like Attracting Cavities) performs better. This first-principles approach is clearly more reliable when exploring unknown chemical space.

This study also makes another important contribution: it establishes a cleaner, more reliable benchmark dataset called RNP-F. The authors found that many existing datasets are full of “noise,” such as crystal structures with poor resolution or overly studied “celebrity” ligands. They removed this problematic data to ensure a fair comparison. This is good for the whole industry, as everyone will now have a more reliable yardstick for evaluating new algorithms.

Finally, the research points to a harsh reality: both AI and traditional docking face a “garbage in, garbage out” problem. The analysis found that both methods have a high “scoring failure rate,” and often the root cause is a problem with the input PDB structure itself. This reminds us that even the most powerful algorithm can’t create high-quality results from thin air. Solid experimental data will always be the foundation of computer-aided drug design.

So, what’s the path forward? The researchers believe it’s not about choosing one over the other, but about combining them. Perhaps one could use co-folding to quickly generate an initial pose, and then use more rigorous docking methods for refinement and scoring. This is like having an experienced detective (docking) guide a rookie with a photographic memory (co-folding). By leveraging the strengths of each, we can find the molecules we’re looking for more efficiently.

📜Title: Comparative Assessment of the Utility of Co-Folding and Docking for Small-Molecule Drug Design

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.09.693161v1

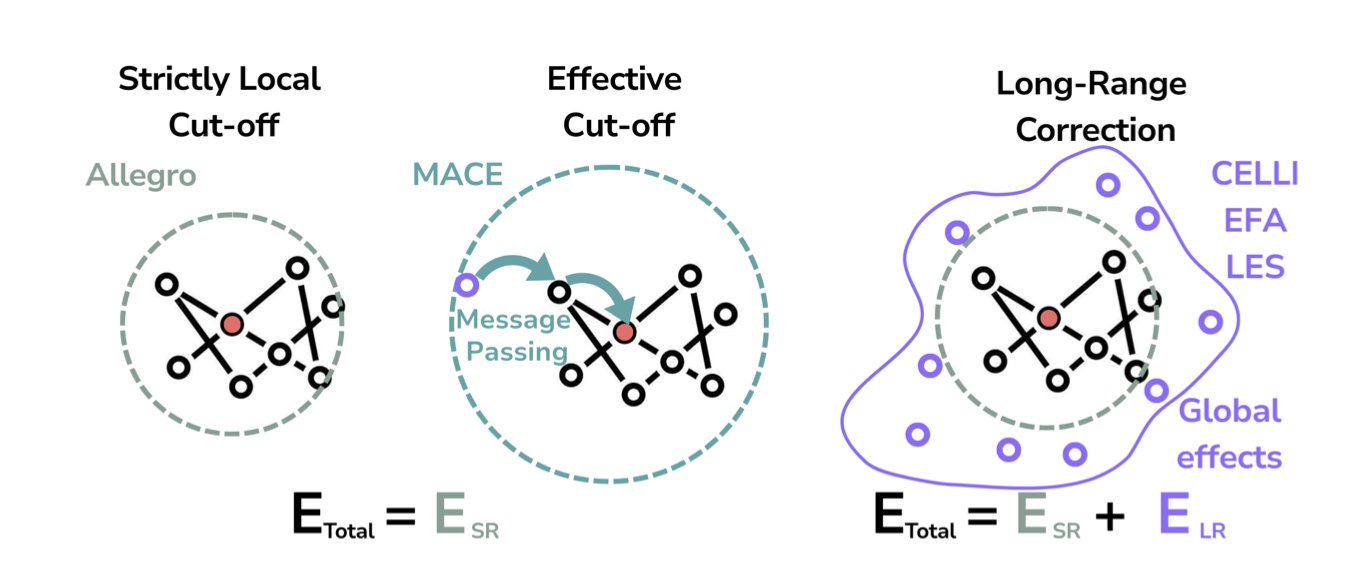

6. AI for Chemistry Simulation: Long-Range Forces are Key, But Not Enough

Anyone in computational chemistry knows that Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) have become very popular. They use neural networks to predict the energy and forces between atoms, running orders of magnitude faster than traditional quantum chemistry calculations while offering higher accuracy than classical force fields. This sounds like a perfect solution, but they have a fatal Achilles’ heel: generalization.

Many MLIPs are “short-sighted.” When calculating the energy of an atom, they only look at its neighbors within a small radius (e.g., 5-10 angstroms). This purely “local” model, like Allegro, handles situations present in its training data very well. But if you ask it to predict a system with a completely new chemical environment it has never seen, it’s likely to be wildly inaccurate. This is like a taxi driver who only knows their own neighborhood; send them to the other side of the city, and they’re completely lost. That’s because in the world of chemistry, many key forces, like electrostatic interactions, are long-range. An atom dozens of angstroms away can still influence your current position.

The authors of this paper seized on this weak point. Instead of the usual random split of training and test sets, they designed a much tougher test. They first used SOAP descriptors (a mathematical tool to “profile” an atom’s local environment) to analyze the entire dataset. Then, they deliberately picked the molecules with the most “unusual” chemical environments—those most different from the mainstream data—and put them in the test set. This is like throwing that neighborhood-bound taxi driver into the most unfamiliar traffic conditions for their driving test. Only this can truly test a model’s ability to generalize.

The results were as expected. The purely local models performed poorly on these “unconventional” tests. But when the authors added long-range correction modules to these models—like CELLI or EFA, which you can think of as giving the driver a GPS—performance improved significantly. This proves that to achieve true generalization, a model must be able to see the bigger picture.

The paper also made an interesting discovery that dashes some unrealistic hopes in the field. Some had hoped that by feeding a model enough energy and force data, a neural network could “figure out” the physical concept of local atomic charge on its own. The authors showed experimentally that this doesn’t work. The model cannot infer accurate atomic charges from scratch. You have to explicitly provide the reference charge for each atom in the training data for it to learn how to assign charges correctly. It’s like teaching a child to paint: you can’t expect them to learn color theory just by looking at black-and-white photos; you have to show them color examples.

Finally, the authors tested these “top-performing” models with long-range corrections on a truly complex system: metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). The internal pore structures and metal-organic ligand interfaces in MOFs create extremely complex electrostatic environments. Here, even the best long-range models started to struggle. This shows that our current long-range correction schemes are still quite basic and have a long way to go before they can simulate such highly non-uniform, complex materials.

This work offers a clear perspective: in the quest for generalizable MLIPs, long-range forces are a hurdle that cannot be bypassed. It also points us in the right direction: we need to develop more powerful long-range physical models and test them with more rigorous, non-random benchmarks. For people in drug discovery or materials design, this means that when using these AI tools, you must be aware of their limitations.

📜Title: Generalization of Long-Range Machine Learning Potentials in Complex Chemical Spaces

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.10989v1

💻Code: https://github.com/tummfm/chemtrain