Table of Contents

- GaugeFixer solves the problem of parameter ambiguity in sequence-function models with an efficient algorithm, allowing researchers to uncover reliable biological mechanisms from massive datasets.

- Researchers cleverly “tricked” AlphaFold2 into generating multiple protein conformations. By combining this with statistical methods, they successfully screened for “transformer” proteins with multiple shapes from a vast pool of proteins.

- DynaMate, a multi-agent framework, can autonomously handle the entire molecular dynamics simulation of a protein-ligand system from start to finish, making a complex and tedious process surprisingly simple.

- Researchers have successfully used existing quantum computers to predict hydration sites in protein pockets with an accuracy comparable to classical methods, signaling the practical arrival of quantum computing in drug discovery.

- AlphaFold3 performs well on predicting single disordered proteins, but when dealing with complex interactions, it shows a “confident stubbornness,” and its predictions are often hard to interpret.

- The latest GUANinE v1.1 benchmark shows that supervised and unsupervised genomic models each have their strengths. Combining them is the future of genomic sequence modeling.

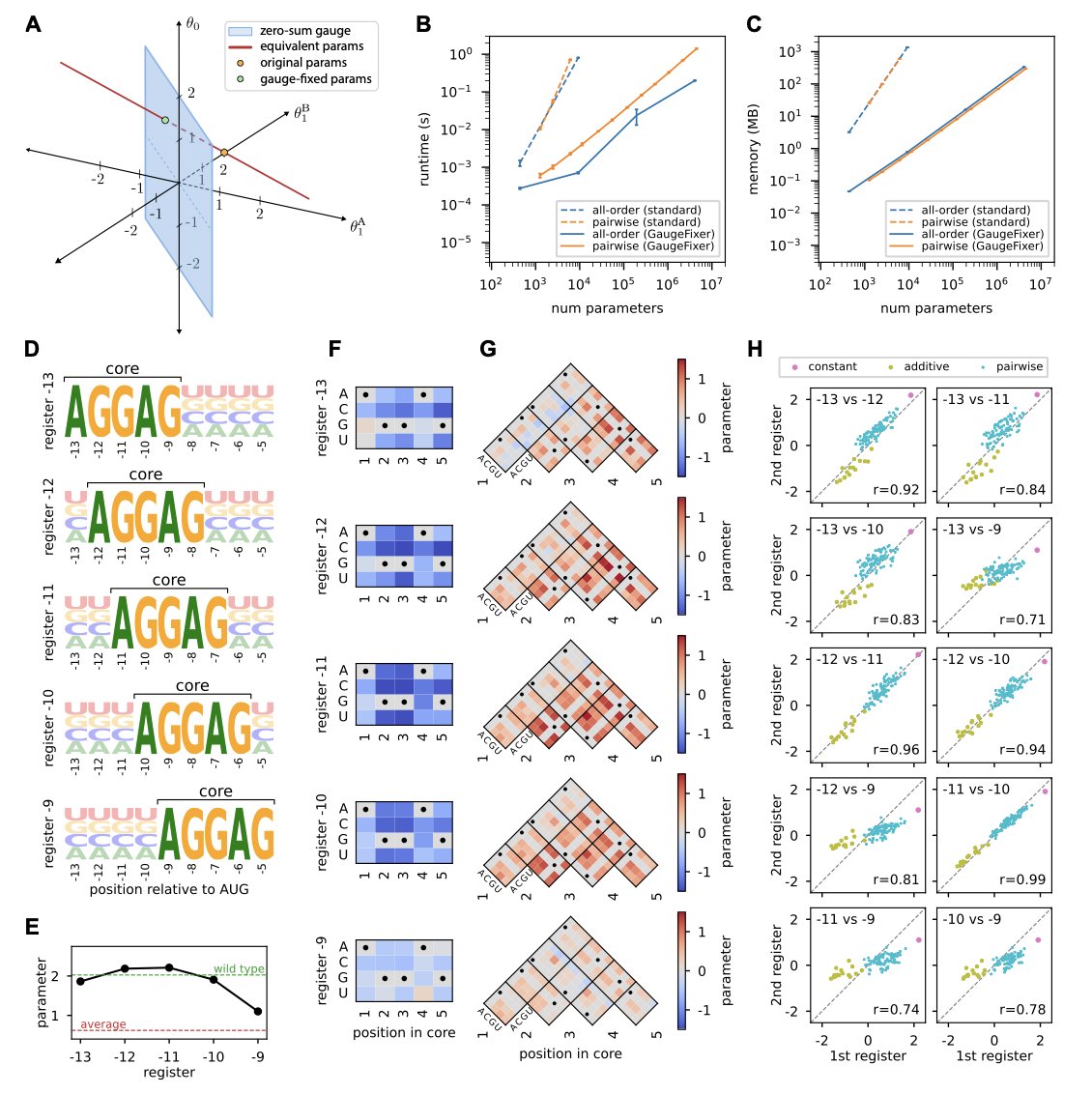

1. GaugeFixer: A Tool to Fix Parameter Ambiguity in Biological Models

When we build models in biology, especially to study how sequence determines function, we often run into a frustrating problem. Imagine you train a complex model to predict the activity of a protein sequence. The model works well and its predictions are accurate. But when you try to open the “black box” to understand how much each amino acid position contributes, you hit a snag. You might find that several completely different sets of parameters can produce the exact same prediction results.

This is known as “gauge freedom,” or parameter non-uniqueness. It’s like navigation: several different maps (parameter sets) can all lead you to the same destination (correct prediction), but each map uses a different coordinate system. If you want to use one of these maps to find the next treasure, which one should you trust? This makes interpreting the model extremely difficult because we can’t be sure of the biological meaning of the parameters.

A new Python toolkit called GaugeFixer is designed to solve this problem. You can think of it as a “map calibrator.” It takes all these maps with different coordinate systems and aligns them to a single, standard “gauge.” This makes the model’s parameters unique and comparable.

The most impressive part of this tool is its algorithmic efficiency. The authors used the mathematical structure of gauge-fixing projections to design an algorithm where computation time and memory usage scale linearly with the number of parameters.

What does this mean for those of us doing computational work? It means the tool runs very fast. You can calibrate even massive models with millions of parameters on your own workstation or laptop, without needing to compete for time on a supercomputer. This significantly lowers the barrier to entry.

To prove its worth, the authors applied GaugeFixer to a classic biological problem: analyzing the Shine-Dalgarno sequence in E. coli. This is a key sequence that determines how a ribosome binds and initiates translation. After calibrating the model with GaugeFixer, they clearly revealed subtle differences in ribosome binding preferences at different positions around the start codon. These detailed biological insights would likely have been lost in the “noise” of ambiguous parameters in an uncalibrated model. It’s like wiping the dust off a gem to reveal its original brilliance.

GaugeFixer is also designed to be flexible. It supports not only global models but also hierarchical models, allowing researchers to choose the calibration method that best fits their biological question.

For colleagues who want to try it out, the tool is easy to get and use. It’s an open-source Python package that can be installed directly with pip. The authors have also provided thorough documentation and source code. This shows they hope the tool will become a standard part of the community’s workflow, helping everyone build more reliable and interpretable biological models.

📜Paper: GaugeFixer: Overcoming Parameter Non-identifiability in Models of Sequence-Function Relationships

🌐Biorxiv: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.08.693054v1

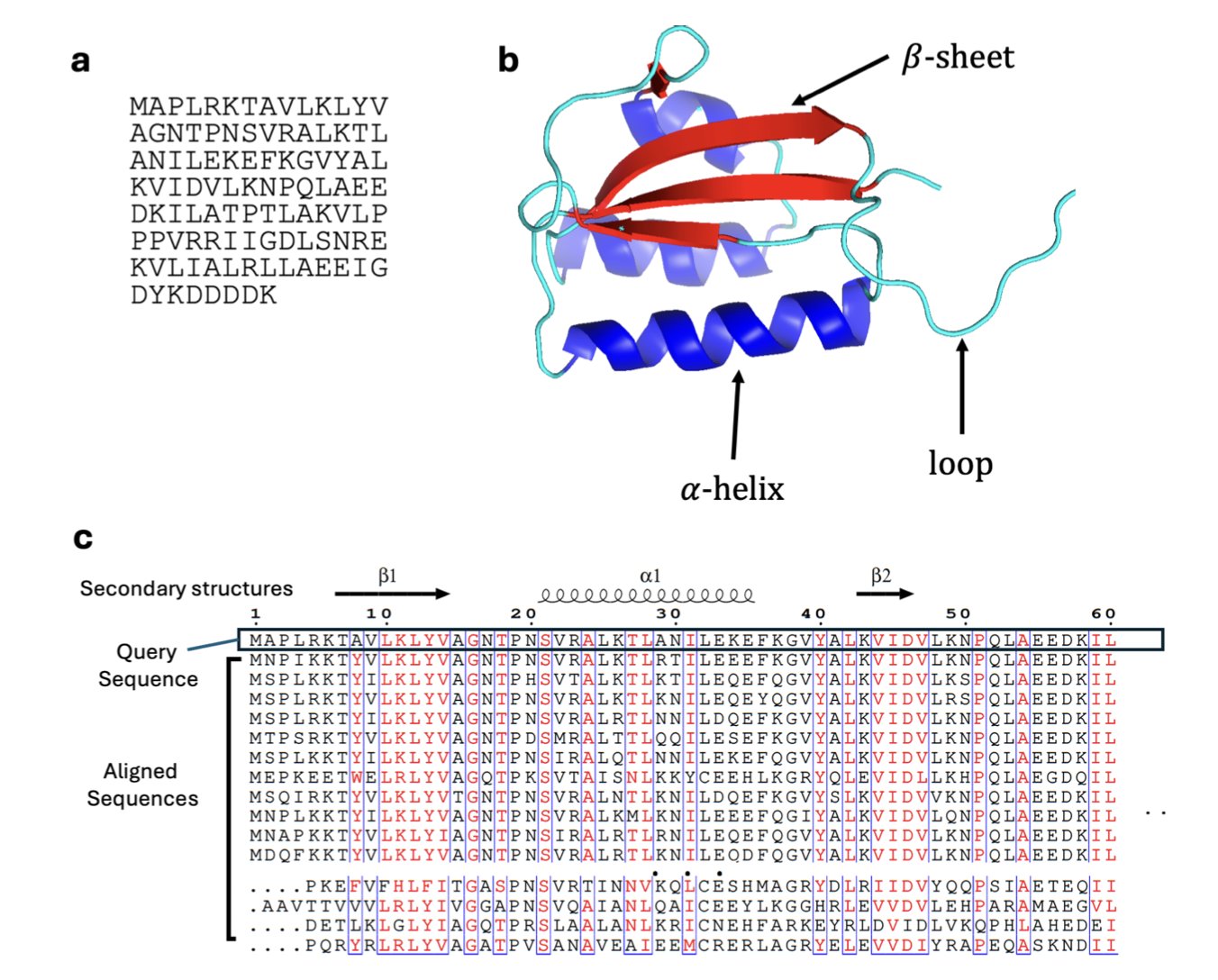

2. A New Trick for AlphaFold2: Predicting ‘Transformer’ Proteins

Inside our cells, most proteins are like precisely engineered parts, with a single, fixed 3D shape to perform a specific job. But there are exceptions. These are the “transformers” of the protein world, known academically as “Metamorphic Proteins.” Like a Swiss Army knife, these proteins can switch between two or more distinct, stable structures, with each structure corresponding to a different biological function.

Finding these “transformers” has always been a challenge. Traditional experimental methods, like X-ray crystallography or NMR, usually capture only the most stable and common form of a protein, making it hard to see its other shapes.

The arrival of AlphaFold2 changed the game for protein structure prediction, but it has its own quirks. It was designed to predict the single most likely, lowest-energy structure. You give it an amino acid sequence, and it does its best to give you the most reliable answer. This works perfectly for the vast majority of single-structure proteins. But for metamorphic proteins, it means we might only see one of their forms, missing out on other equally important ones.

Making AlphaFold2 “Hesitate”

The clever part of this new research is that the scientists didn’t try to change AlphaFold2 itself. Instead, they figured out how to manipulate its input. AlphaFold2 relies heavily on an input called a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA), which essentially tells it what the protein’s evolutionary relatives look like.

The researchers developed a sampling method called SMICE. Instead of feeding AlphaFold2 all the information about its evolutionary relatives at once, SMICE selectively feeds it different “circles of relatives” in batches. This is like giving a detective different sets of clues from various sources. With each slightly different combination of clues, the detective might arrive at a different conclusion about the case.

By doing this, they induced AlphaFold2 to make multiple predictions for the same protein sequence, each time potentially generating a slightly different yet plausible structure. This gave them a set of “possible shapes” for the protein, known as a conformational ensemble.

Finding the Pattern in a Pile of Structures

Now we have a large collection of predicted 3D structures. The next crucial step is to figure out whether this collection represents a true “transformer” protein or just random “noise” from AlphaFold2’s prediction process.

This is where the authors brought in statistical learning. They extracted a few key quantitative features from the set of structures:

- Structural Diversity: How different are the structures from one another? If they are all clustered together and look similar, it’s likely a normal protein. If they clearly separate into distinct “structural families,” it’s probably a “transformer.”

- Cluster Shape: Do the structures form one large cluster or two or more separate clusters? This directly reflects the modality of the conformational space.

- Prediction Confidence: How confident is AlphaFold2 in each of its predicted structures (pLDDT score)? A true metamorphic protein might get high confidence scores for two or more of its different forms.

They fed this feature data into a random forest classifier. After training the model on a dataset of known metamorphic and single-structure proteins, it learned to recognize the characteristic patterns of a “transformer.” The model’s ability to distinguish between them was quite good, with an average AUC of 0.869, meaning it makes the right call most of the time.

Discoveries in Practice

To see how well the theory and model worked in practice, the researchers applied their classifier to 600 proteins randomly selected from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The results were exciting. The model flagged several new potential metamorphic proteins. One example is the 40S ribosomal protein S30, which is known to have antimicrobial functions. The flexibility of its function might be related to dynamic changes in its structure.

The significance of this method is that it provides an efficient computational tool for large-scale screening and discovery of metamorphic proteins. For drug development, this opens a new door. Traditional drug design often targets a binding pocket on a protein’s single, stable structure. But if the target is a “transformer,” we might be able to design a drug that specifically binds to one of its particular forms, “locking” it in a non-functional or specific functional state. This could lead to entirely new mechanisms of drug action.

Of course, this method is currently a powerful screening tool. Any predicted candidate protein will ultimately need to be validated by experimental methods. But it undoubtedly narrows down the search space, allowing us to more accurately find the most interesting “transformers” in the biological world, which may also play key roles in disease.

📜Title: Classifying Metamorphic versus Single-Fold Proteins with Statistical Learning and AlphaFold2

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.10066v1

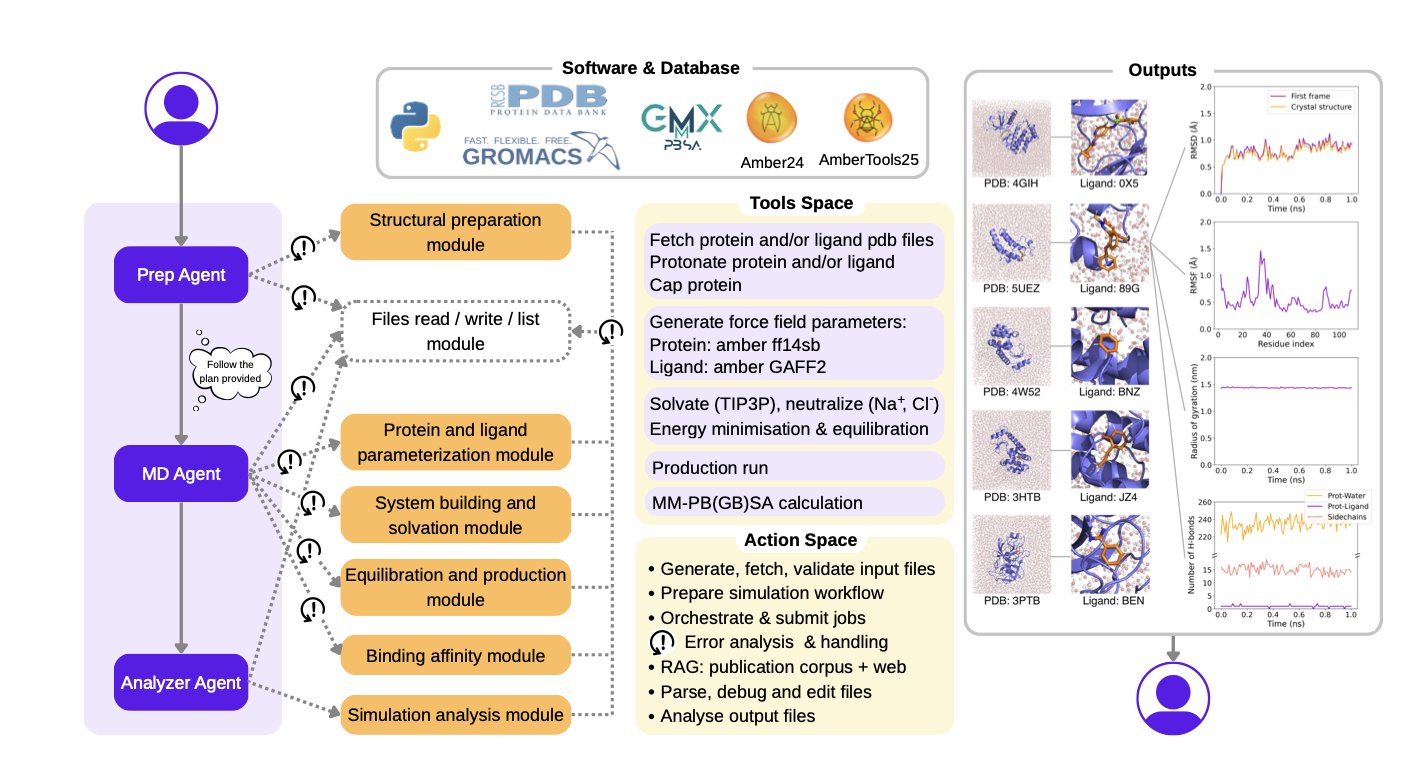

3. DynaMate: A Self-Correcting AI for End-to-End Molecular Dynamics

Anyone who has run Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations knows how tedious the work can be. To prepare a protein-ligand complex system, you need to process PDB files, parameterize the ligand, choose the right force field and water box, and then run energy minimization, heating, and equilibration before you even get to the production simulation. The whole process is a long chain of steps involving multiple tools (GROMACS, Amber, OpenMM, etc.). If any step goes wrong, hours or even days of computation time are wasted.

DynaMate was created to solve this pain point. It’s not just a simple script; it’s an autonomous agent system based on a Large Language Model. You can think of it as an experienced computational chemist.

Here’s how it works: You give it a task, like “run a 100-nanosecond MD simulation for this protein and this ligand, and calculate the binding free energy.”

DynaMate’s internal “Planner Agent” first breaks this big task into a series of smaller, concrete steps. For example:

1. Prepare the protein structure.

2. Prepare the ligand structure and generate force field parameters.

3. Build the complex system.

4. Run energy minimization.

5. …

6. Run the production simulation.

7. Calculate the MM/PB(GB)SA binding free energy.

Then, it assigns these small tasks to different “Worker Agents” to execute. These worker agents know how to call various specialized biochemical software tools.

The most impressive part of this system is its intelligence. Traditional automation workflows are linear; if one step fails, the whole thing crashes. DynaMate is different. It has the ability to correct itself. For example, if the default antechamber tool fails while generating force field parameters for a novel ligand, the system doesn’t just stop with an error. It recognizes the error, might search online for the error code, or even use an integrated PaperQA tool to look up relevant literature for alternative methods or parameters for that type of molecule. Then, it will try to re-execute the task with the new approach. This adaptability greatly increases the success rate of simulations.

The researchers tested DynaMate on 12 benchmark systems of varying complexity, and the results showed that it can independently complete simulations and analysis from start to finish.

For people in drug discovery, the main concern is the accuracy of its binding free energy calculations.

The paper reports that the results calculated with the MM/PB(GB)SA method show a good correlation with experimental data. This means we can use it to quickly screen and evaluate a series of compounds to see which molecules might bind more strongly to a target, guiding the next steps in chemical synthesis.

The framework’s architecture is modular, so it will be easy to integrate new tools in the future or expand to more complex systems like membrane proteins, DNA, or even multimers with multiple ligands. If this tool becomes stable and widely adopted, it could free computational chemists from a lot of repetitive, tedious preparation work, allowing us to focus more on analyzing results and gaining scientific insights.

📜Title: DynaMate: An Autonomous Agent for Protein-Ligand Molecular Dynamics Simulations

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.10034v1

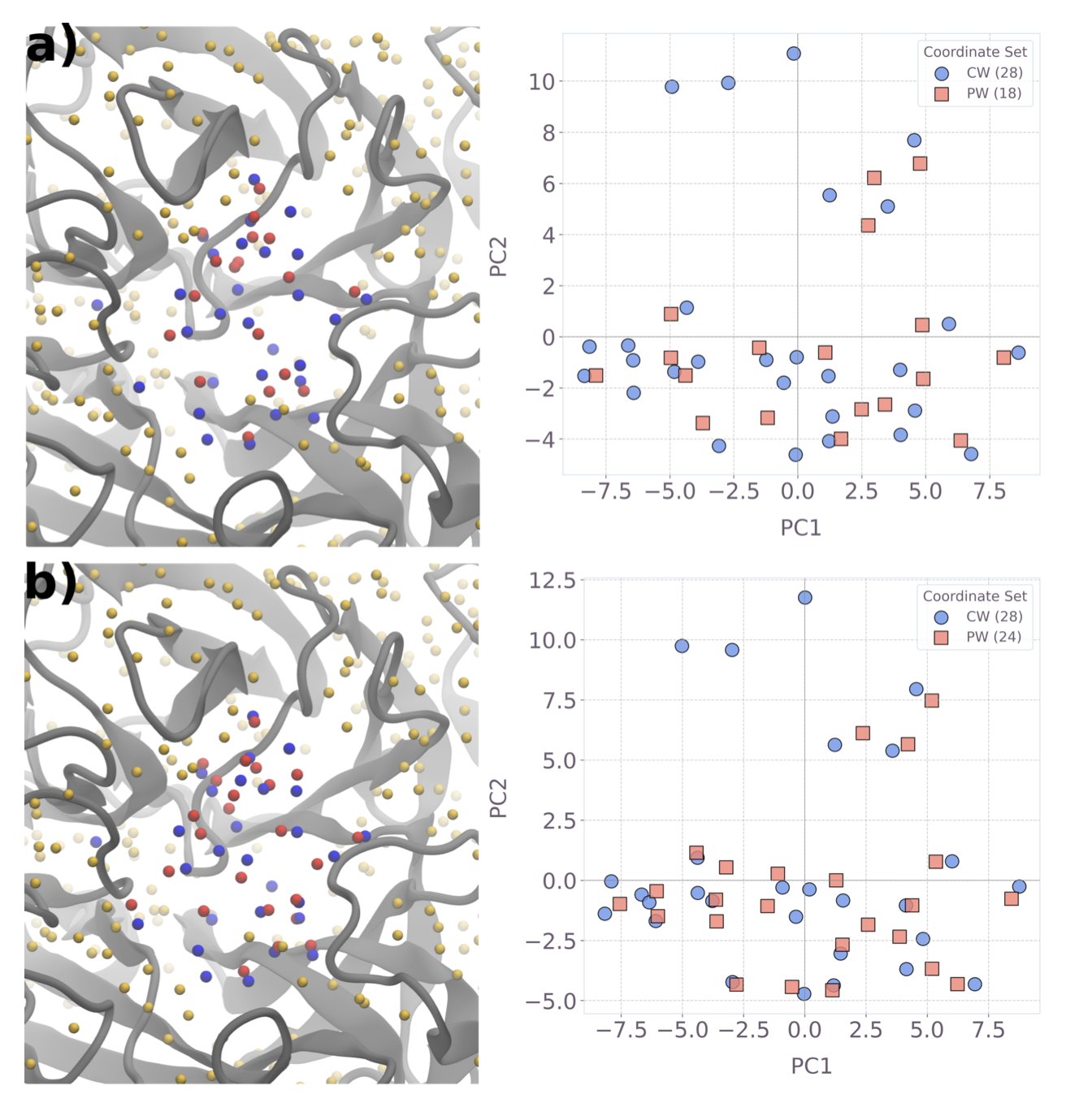

4. Quantum Computing Predicts Protein Hydration Sites in a New Approach for Drug Discovery

In drug design, water molecules in a protein target’s pocket are something we both love and hate. They’re like invisible furniture in a room. The drug molecule (ligand) you’re designing has to cleverly avoid or use them to find the most comfortable binding pose. A tiny difference in a water molecule’s position can be the difference between a highly effective drug and a useless one. The problem is, accurately predicting the positions of these water molecules has always been a tough nut to crack in computational chemistry.

The classical methods we currently use, like 3D-RISM, give us a probability distribution map of where water molecules might be, like a blurry cloud. But they don’t explicitly tell you: “A water molecule is right here, and this is the lowest energy state.” Drug chemists need a more definitive answer.

The authors of this paper took a different approach. Instead of trying to solve this hard problem head-on, they repackaged it into a problem that quantum computers are good at solving.

First, they use the classical 3D-RISM method. This step essentially marks out the “possible activity range” for the water molecules.

Second, they reframe the problem. They ask: “Among all these possible sites, how can we place water molecules so that the total energy of the system is at its minimum?” This is essentially a combinatorial optimization problem. Finding the single best solution out of thousands of possibilities is exactly where quantum computing has potential. The authors constructed the problem as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) model. You can think of it as giving each possible water molecule position a switch (0 or 1, for on or off) and then finding the combination of switches that results in the lowest total energy.

Third, they give the problem to a quantum computer. They ran this QUBO model on IBM’s Heron quantum device, using up to 123 qubits for the largest system. This is a hybrid strategy: a classical computer does the rough calculation, and the quantum computer handles the fine-tuning and optimization.

What were the results? Quite good. Compared to a classical simulated annealing algorithm, the quantum solver had a higher success rate at finding the optimal solution. This means that when exploring a vast space of possibilities, the quantum computer is less likely to get “lost” than classical algorithms and can more reliably find that lowest-energy “sweet spot.”

The biggest significance of this work is its practicality. It didn’t just stay at the theoretical level; it produced competitive results directly on today’s imperfect Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. This proves that hybrid quantum-classical methods are a viable path forward right now.

The authors also made resource predictions. They believe that as quantum hardware improves, we might be able to handle more complex and larger protein systems within a few years. For researchers on the front lines, this means a more powerful tool could soon be in our toolkit, helping us design drug molecules more precisely and avoid those pesky water molecule traps. This is no longer a distant future but a clear, visible roadmap.

📜Title: Practical protein-pocket hydration-site prediction for drug discovery on a quantum computer

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.08390v1

5. AF3 on Disordered Proteins: Solid on Monomers, Unpredictable for Complexes

In drug development labs, the worst thing isn’t an AI that says, “I don’t know.” It’s an AI that confidently gives you the wrong answer. A recent study evaluated the performance of AlphaFold3 (AF3) in predicting Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs). These proteins are like floating noodles; they have no fixed 3D structure but play crucial roles in life.

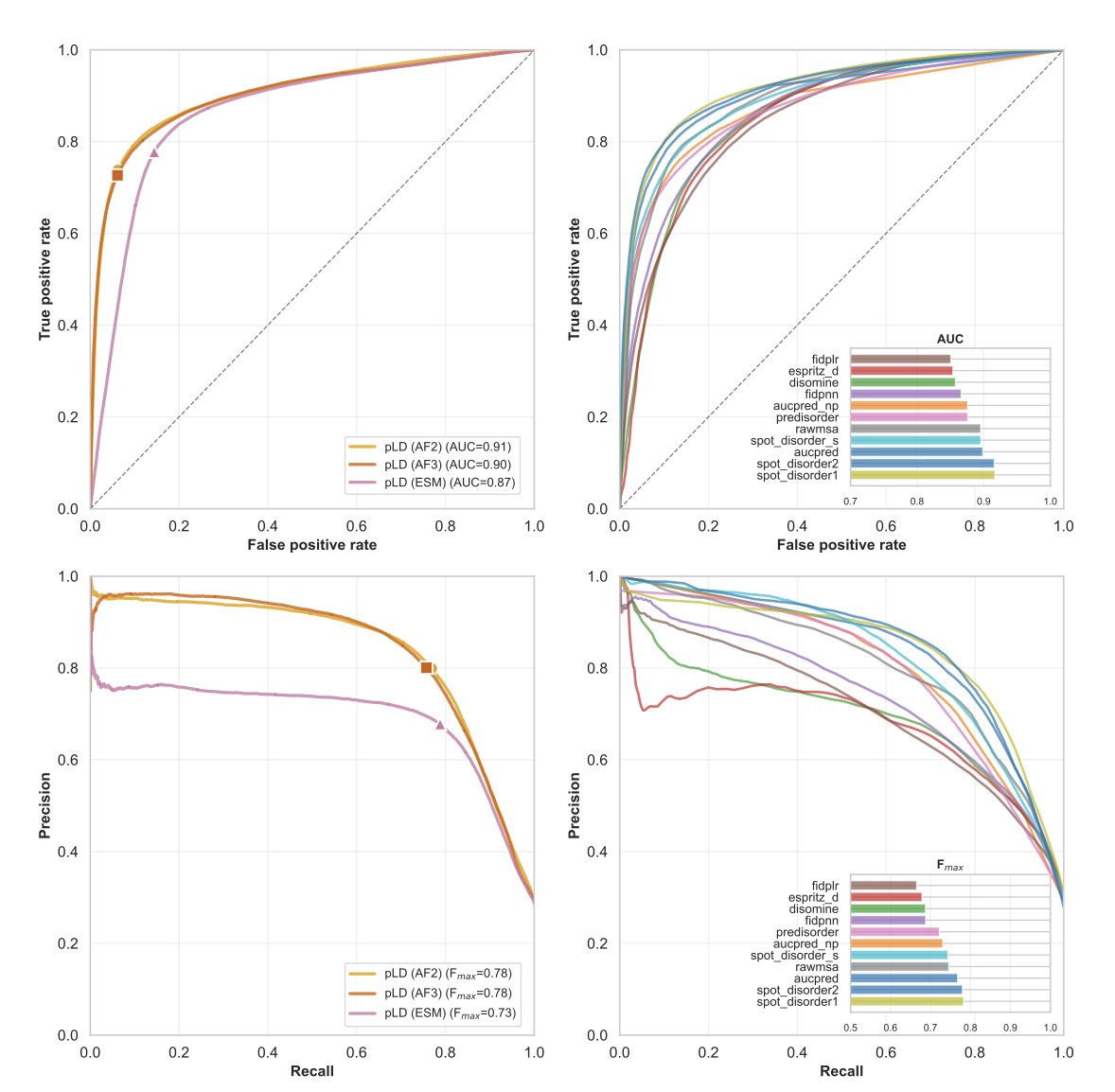

First, let’s look at single proteins (monomers). If you just want to know which parts of a protein are disordered, AF3 is still the reliable top student you remember. Its confidence score (pLDDT) works very well, with a Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.69, performing on par with its predecessor, AF2, and other tools specialized for predicting disordered regions. This ability seems to be something it “learned” from the training data rather than a feature of the model’s architecture itself.

But things get tricky when you move to complexes (multimers). Although AF3’s overall score (DockQ) is similar to AF2’s, around 0.56, its behavior has changed. The researchers found that when AF3 makes a wrong prediction, it does so with extreme confidence. No matter how many times you run it, it converges to the same incorrect structure. This is like a student who has memorized a single wrong answer and gives it for every version of the question. This strong structural bias masks the protein’s actual physical flexibility.

Why does this happen? It might be related to the Diffusion Model introduced in AF3. In the past, we could use physical features like hydrophobicity or charge to explain why a model’s prediction was good or bad. But with AF3, traditional structural features can only explain 42% of its performance variation. In other words, the model has become more of a black box, and its decision-making logic is beyond what traditional structural biology descriptors can capture.

Another headache for drug developers is induced folding. Some protein fragments are disordered when they are free-floating but fold into a fixed shape only when they meet a specific binding partner. Both AF3 and AF2 struggle with this. They can predict the final folded state, but they have a hard time accurately identifying which fragments are these “Molecular Recognition Features” (MoRFs).

Perhaps algorithmic innovation alone (like replacing Transformers with Diffusion Models) is not enough. If the training data still lacks diversity in disordered proteins, the AI will continue to see the world with a bias. For anyone trying to use AI to find new targets, blindly trusting its predictions could lead an entire project astray. We may need more diverse datasets or to use ensemble sampling methods to break this “confident error.”

📜Title: AlphaFold3 and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Reliable Monomer Prediction, Unpredictable Multimer Performance

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.12.05.627014v1

6. GUANinE 1.1 Reveals: For Genomic AI Models, You Can Have the Best of Both Worlds

In genomics research, we have a whole arsenal of AI models, and each one claims to be the best. But which one should we actually use? It’s like walking into a hardware store filled with all kinds of hammers and wrenches. If you pick the wrong tool, you’ll mess up the job. The new GUANinE v1.1 benchmark is like a detailed “tool review report” that helps us understand the real capabilities of these models.

The core finding of this report is that different types of models have different “comfort zones.”

Supervised models are like students studying with an answer key. You give them a DNA sequence and tell them the functional label for that sequence (like “promoter” or “enhancer”), and they learn the mapping. So, they perform best on tasks with clear functional annotations, like chromatin accessibility. This isn’t surprising, as it’s exactly what they were trained to do.

In contrast, unsupervised models, which include the popular Genomic Large Language Models, are more like linguists. You drop them into a library full of ancient texts (raw DNA sequences) without a dictionary or a translation. They have to figure out the language’s grammar, vocabulary, and deep structure on their own. As a result, they have a remarkable intuition for the “grammar” of evolution—that is, which sequences have been preserved over millions of years. That’s why they completely outperform supervised models on tasks related to evolutionary conservation. This tells us they aren’t competitors; they are partners with different specializations.

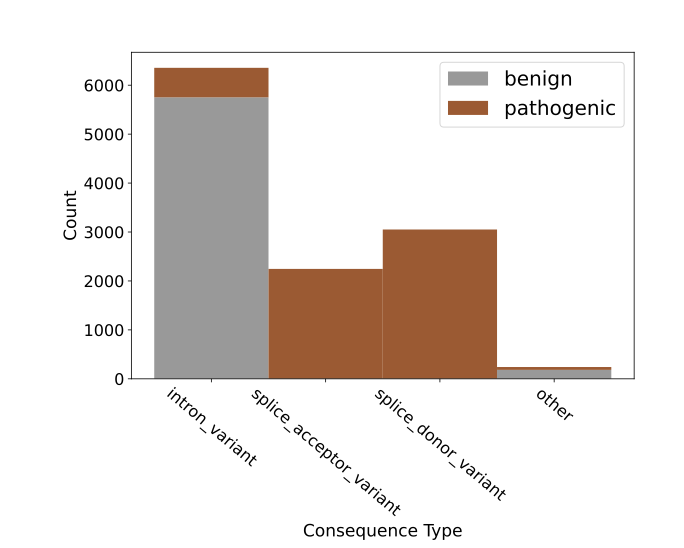

The report also introduces two new, very difficult tasks that go to the heart of drug development and clinical diagnostics: cadd-snv (predicting proxy deleteriousness) and clinvar-snv (predicting clinical pathogenicity). The distinction here is subtle but crucial. A model might accurately judge that a gene variant “looks bad,” for instance, because it could change a key amino acid. This is called “deleteriousness.” But that’s like a mechanic saying, “A part in your engine looks off.” Will that part actually cause the car to break down? That’s “pathogenicity.” The leap from “looks bad” to “will definitely cause a breakdown” is huge. The test results from GUANinE v1.1 confirm that this gap still exists. Models are decent at predicting deleteriousness but are often wrong when it comes to clinical pathogenicity. This is a sober reminder for anyone trying to use AI to interpret genetic variants.

The researchers also explored a very practical engineering question: with limited computing resources, should we bet on a model with more parameters or one that can “see” further (a larger context window)? They found that it’s not as simple as “bigger is better.” The model’s parameter density and complexity are just as important. It’s like choosing a camera lens. Sometimes, a macro lens with a narrow field of view but incredible sharpness is more useful than a wide-angle lens that can capture the whole landscape. Which one you use depends on the problem you’re trying to solve.

Finally, the paper points the way forward: hybrid models. Since supervised and unsupervised models each have their strengths, why not combine them? The researchers combined an unsupervised model (NT-v2-500m) with a supervised model (Sei) and found that for predicting variant effects, this “hybrid” combination outperformed either model alone. It’s like having a team with both a linguist who understands ancient texts and a top student who knows the standard curriculum. When faced with a complex problem, their combined effort is far greater than the sum of their parts. This is very likely what the next generation of genomic sequence modeling will look like.

📜Title: GUANinE v1.1 Reveals Complementarity of Supervised and Genomic Language Models

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.06.692772v1