Table of Contents

- BioDynaGen created a unified language that lets AI understand proteins, small molecules, and their dynamic binding process, which is closer to biological reality than static models.

- Current machine learning scoring functions perform poorly on new targets, but large-scale pretraining and a small amount of target-specific data can significantly improve their generalization.

- The CI-LLM framework teaches AI how to understand, predict, and design complex polymers from scratch by breaking them down into structural units familiar to chemists.

- GAMIC combines graph neural networks with text descriptions to make mid-sized large language models better at chemistry, improving the accuracy of molecular property prediction.

- BIOARC shows that customizing neural network architectures for biological data can lead to a leap in performance with a very small computational budget.

- Sparse autoencoders can help us look inside antibody language models, but there is still a long way to go to truly control them to generate specific molecules.

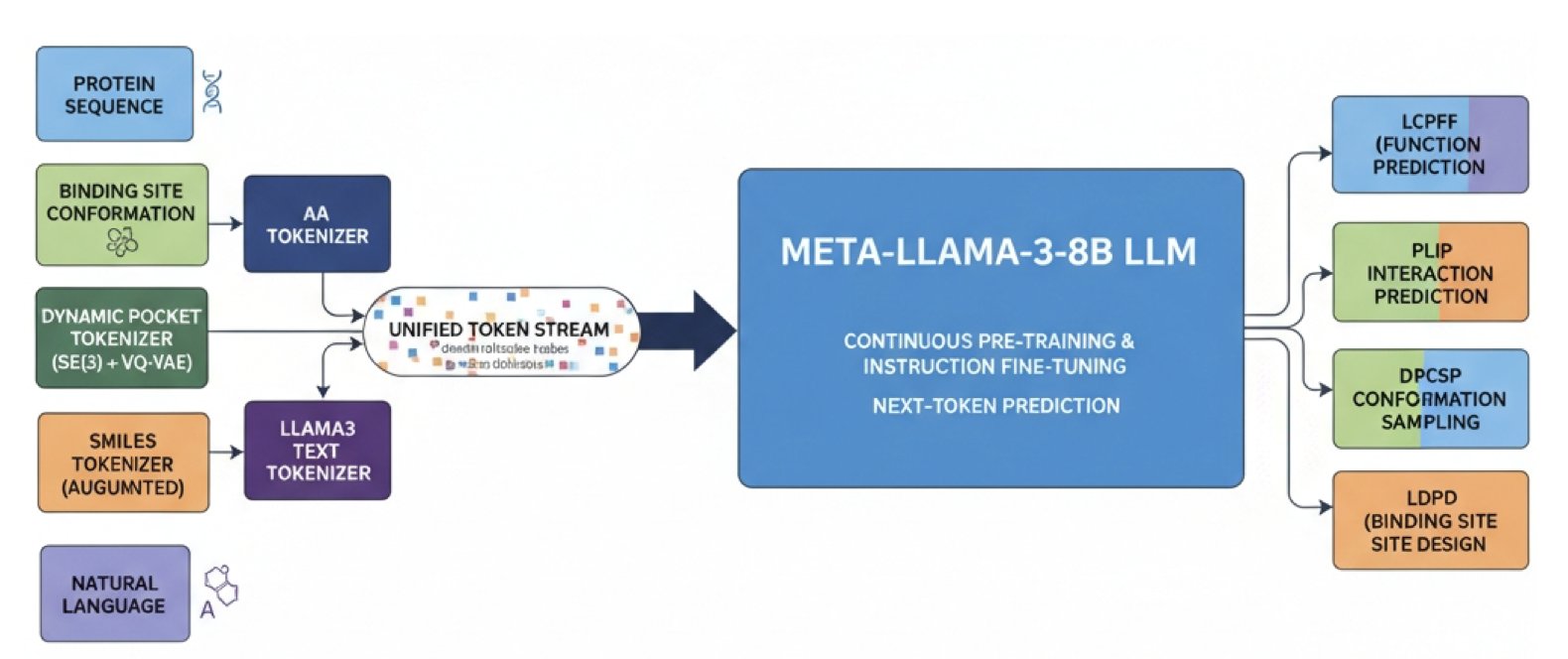

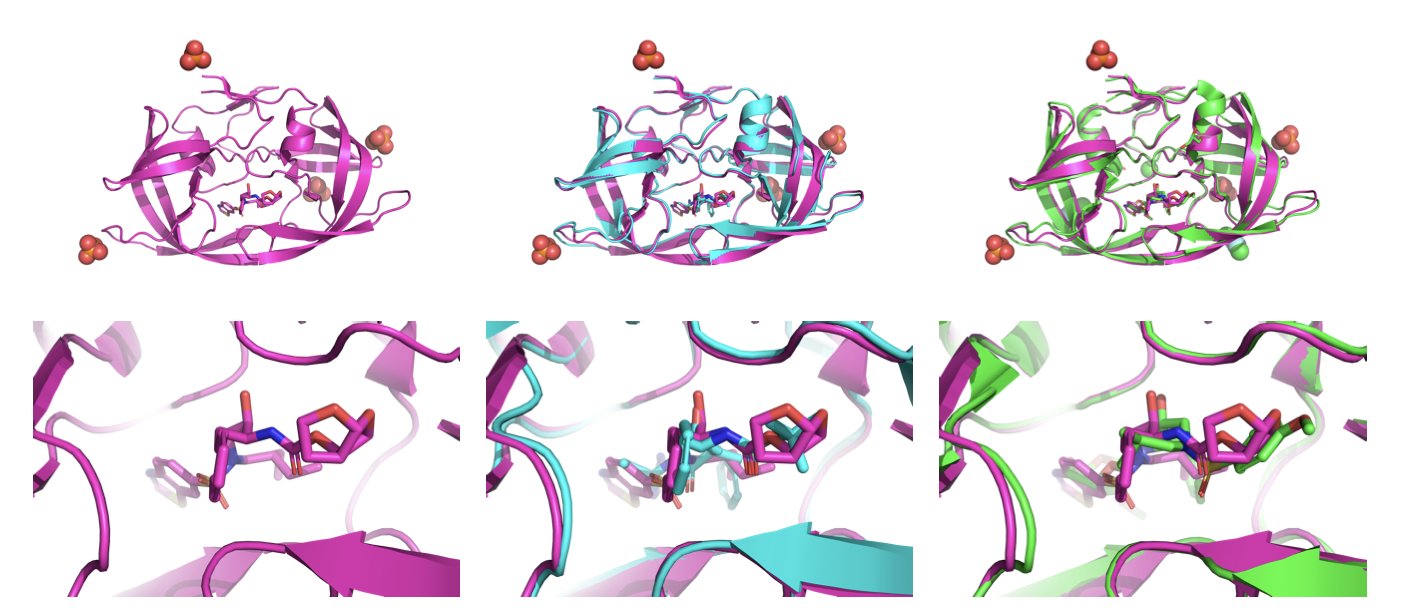

1. BioDynaGen: AI Sees How Proteins and Drugs Dynamically Bind for the First Time

In drug discovery, the binding of a protein and a drug is often compared to a “lock and key,” but this is too simple. A real protein target is more like a piece of squishy clay in water, its shape always changing slightly. When a drug “key” gets close, the “clay” actively changes its shape to accommodate it better. This dynamic process is called “induced fit.”

Most older computational models could only handle static snapshots of proteins, like images from X-ray crystallography. While useful, this approach misses the crucial time dimension. It’s like trying to understand a full dance by looking at a single still photograph of the dancer.

BioDynaGen’s goal is to teach AI to understand this molecular “dance.”

How does it work?

The idea is to translate all the information describing this “dance” into a single, unified language that AI can understand. This information includes: 1. Protein sequence: The amino acid sequence of the protein. 2. Small molecule SMILES: The chemical language for molecular structures. 3. Natural language: The words scientists use to describe biological processes. 4. Dynamic binding pocket conformations: The core of the work—a continuous animation of how the protein’s pocket changes over time.

There are already good methods for turning the first three types of information into tokens for AI. The challenge was the fourth point: how do you encode a continuously changing 3D pocket shape into discrete tokens?

BioDynaGen designed a special dynamic binding site conformation tokenizer. You can think of it as an animation analyst that watches the “video” of the pocket changing from a molecular dynamics simulation and then does two things.

After understanding the “dance,” what can it do?

By mastering this unified language that includes dynamic information, the AI gains new abilities.

First, its predictive power improves. For example, in “ligand-conditioned protein function prediction,” it answers the question: what happens to a protein’s function when a drug molecule binds to it? Because BioDynaGen understands the dynamic binding process, its predictions are more accurate than models that can only analyze static images.

Its generative abilities are just as important.

BioDynaGen takes our understanding of protein-drug interactions from the “static photo” era to the “dynamic video” era. It brings computational tools closer to biological reality and moves us a step closer to precise, rational drug design.

📜Title: A Multi-modal LLM for Dynamic Protein-Ligand Interactions and Generative Molecular Design 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.01.691647v1

2. The Generalization Gap in AI Drug Discovery: How Do Models Handle New Targets?

Drug discovery always involves facing new targets. That makes a paper focused on how machine learning models perform on “entirely new targets” interesting. AI models are getting higher and higher scores on all sorts of benchmark datasets, but are they still effective when put into a real R&D project? This paper’s answer is: it’s a big challenge, but there are ways to solve it.

First, the researchers built a tougher test set, called an “Out-of-Distribution” (OOD) dataset. Standard benchmarks are like practice exams, where the topics are all within the scope of what you’ve studied. An OOD test is like solving a real problem you’ve never seen before. To do this, the researchers specifically chose target proteins with structures that were very different from those in the training data.

The results showed that the machine learning scoring functions that did well on standard tests saw their performance drop sharply on the OOD tests. This suggests that many models may have just memorized patterns in the training set instead of truly learning the underlying physical and chemical principles of protein-ligand interactions. A model’s ability to generalize is one of the biggest challenges facing AI in pharma today. If a model is only effective on “familiar” target families, its value in real projects is limited.

So, how do we solve this? The paper proposes two paths.

The first is “Pretraining.” This concept comes from the field of natural language processing. Before learning the specific task of predicting binding affinity, the model first learns from massive amounts of unlabeled molecular and protein structure data. This is like a medical student having to master anatomy and biochemistry before learning to diagnose specific diseases.

In the paper, the authors used ATOMICA embeddings for large-scale self-supervised pretraining. This lets the model learn universal structural patterns on its own, without being given the “answers” for binding affinity—things like the chemical environment around a hydrogen bond acceptor or the shape of a hydrophobic pocket. With this foundational knowledge, the model finds it easier to connect the dots when learning to predict binding affinity and apply its knowledge to new targets. The data shows that after pretraining, the model’s performance on the OOD test set improved. It didn’t completely close the performance gap, but it was a step in the right direction.

The second path is “Fine-tuning,” which is closer to how things work in the real world. In a drug discovery project, we always get some experimental activity data for a new target, even if there isn’t much at first. The study found that using this limited, target-specific experimental data to fine-tune a pretrained model can significantly improve its predictive accuracy for that target.

This is like an experienced doctor who, after seeing just a few cases of a rare disease, can combine that information with their existing knowledge to make an accurate diagnosis for a new patient. This strategy fits well with the actual workflow of drug discovery: use an AI model for large-scale virtual screening, find hit compounds, validate them with experiments, and then feed the new experimental data back into the model to make it smarter about that specific project.

This paper gives us a sober view of the limitations of AI models but also points toward a viable path forward. It reminds us not to blindly trust high scores on benchmarks and confirms that the “large-scale pretraining + fine-tuning with a small amount of project data” approach works. This way, AI models can hopefully evolve from a “black box” that only works on specific datasets into a tool that can work alongside R&D scientists and grow with the project.

📜Title: Generalization Beyond Benchmarks: Evaluating Learnable Protein-Ligand Scoring Functions on Unseen Targets 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.05386

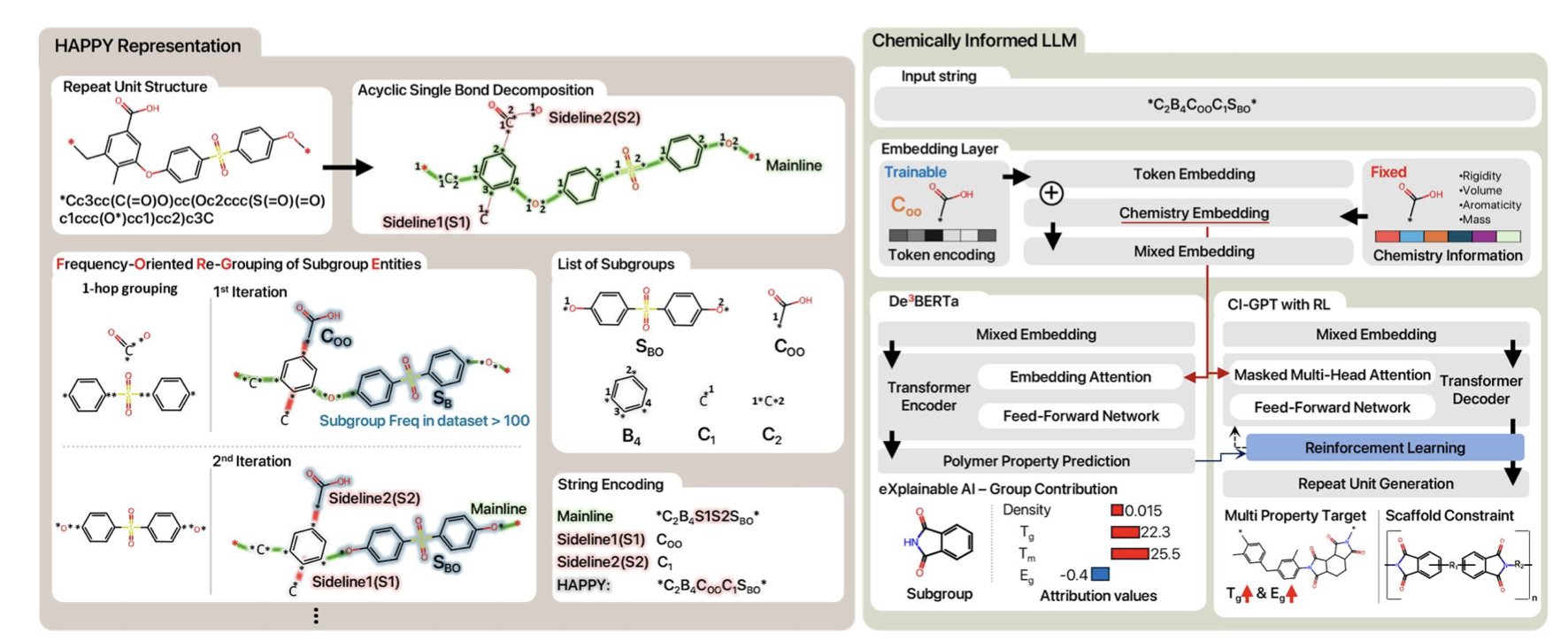

3. CI-LLM: Teaching Large Models to Think About Polymers Like a Chemist

Getting a machine to understand complex long-chain polymers is a tough problem in the field. When describing polymers, traditional SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings are like reciting a long novel word-for-word, making it hard to grasp core chemical concepts like repeat units and backbone structures. It is difficult for a machine to understand this crucial structural information from a long string of repeating characters.

The CI-LLM (Chemistry Integrated Language Model) framework offers a solution: teach AI to learn about polymers using the language of chemists.

Hierarchical abstraction lets AI understand chemical structure

The researchers developed a representation method called HAPPY (Hierarchically Abstracted Repeat Units). It takes a complex polymer structure and, like peeling an onion, breaks it down layer by layer into chemically meaningful substructures or groups.

This is like teaching a child about a car by first pointing out the wheels, the doors, and the engine, instead of starting with a single screw. HAPPY breaks down polymers into chemical fragments like repeat units and end groups, allowing a Large Language Model (LLM) to get a full picture of the molecule’s composition, from the big picture down to the details.

Forward prediction: fast and accurate

With this new “language,” predicting properties becomes simple. The framework’s De3BERTa model not only processes text sequences but also directly incorporates chemical descriptors like molecular weight and the number of functional groups. This is like having detailed background notes and a glossary right next to you while doing a reading comprehension exercise.

As a result, the model is faster at inferring key properties like glass transition temperature and band gap, and its accuracy surpasses that of traditional SMILES-based models. The model can therefore understand the relationship between chemical structure and properties, instead of just guessing in the dark.

Inverse design: creating molecules from requirements

After predicting properties, the next goal is “inverse design”—designing a molecule that has the properties you want.

The framework’s CI-GPT model is used for this. It is trained through Reinforcement Learning, constantly trying and failing until it generates a polymer structure that meets the preset performance targets, much like an experienced chemist optimizing a formula in the lab.

It can handle multi-objective optimization problems, such as requiring both high strength and high flexibility, even though these two properties often conflict in chemistry. The model can also innovate while keeping a specific chemical scaffold, which is very useful for medicinal chemistry and materials development.

Interpretability: knowing “why”

This model isn’t a “black box.” The researchers used a method called Integrated Gradients to see which chemical groups played a key role in the model’s decisions.

For example, the model might point out that a polymer’s high glass transition temperature is mainly due to the phenyl rings in its backbone. This kind of insight can directly guide experimental chemists in designing and optimizing molecules more rationally, reducing the reliance on intuition and extensive trial and error. CI-LLM addresses the problems of data and complexity and provides a new tool for understanding polymer chemistry.

📜Title: Chemistry Integrated Language Model using Hierarchically Abstracted Repeat Units for Polymer Informatics 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.06301

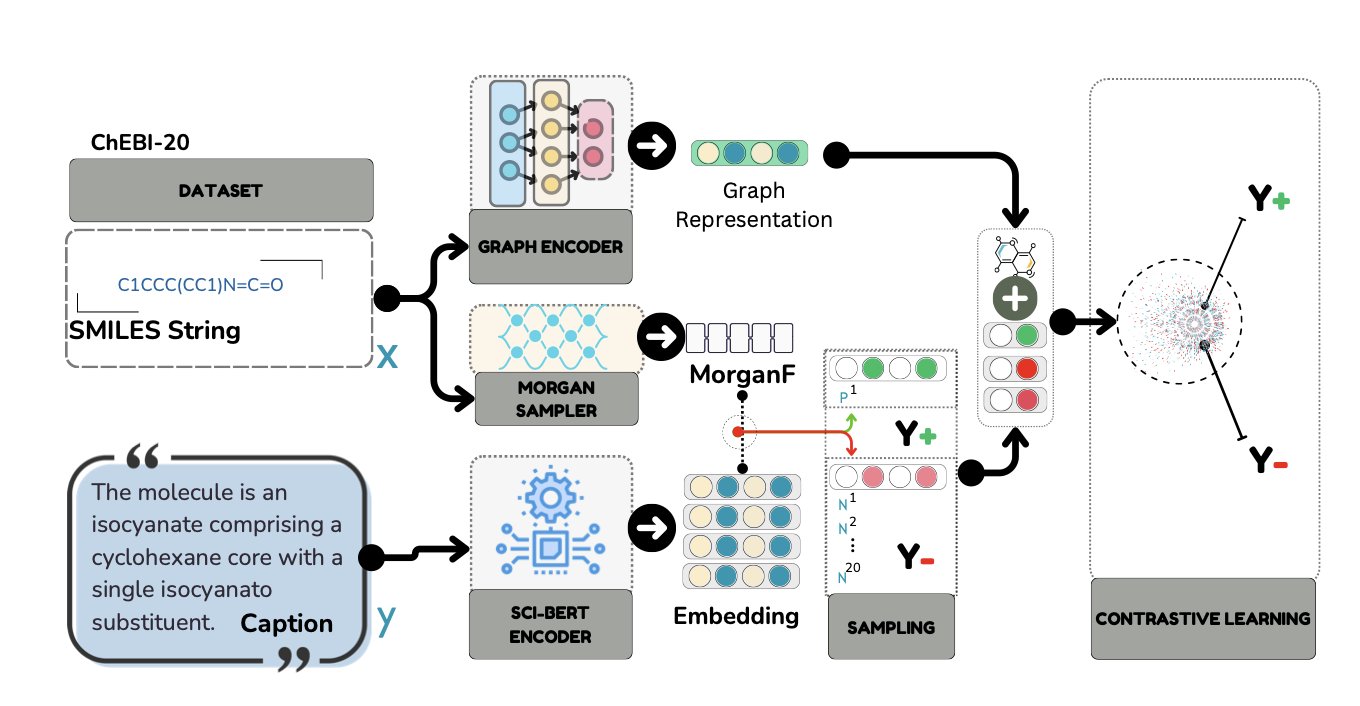

4. GAMIC: Graph Neural Networks Help Large Language Models Understand Molecules

The drug development field is always looking for more efficient ways to predict molecular properties. Traditional methods convert molecular structures into text like SMILES strings, which are then fed to Large Language Models (LLMs). This process loses key information about the molecule’s 3D spatial structure and the interactions between its atoms.

The GAMIC method offers a new approach: give the model both the molecule’s text information and its structural graph at the same time.

GAMIC first uses Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to learn the molecule’s structural information, solving the problem of traditional methods that rely on Morgan fingerprints and lose structural detail. Then, through a contrastive learning framework, it aligns the graph features learned by the GNN with the molecule’s text description. After this training, the model learns to connect abstract molecular graphs with specific chemical concepts.

When selecting learning examples for the model, the researchers used a Maximum Marginal Relevance (MMR) strategy. For instance, to teach the model about “kinase inhibitors,” MMR would select similar inhibitors as positive examples for the target molecule, while also choosing structurally different inhibitors to supplement them. This prevents the model from only recognizing a specific type of structure.

Experimental results show that GAMIC outperformed previous methods on several tasks, including molecular property prediction and chemical reaction yield prediction, with some metrics improving by up to 20%. This demonstrates that less computationally expensive, mid-sized large language models can have their performance significantly boosted by integrating structural information, offering a more viable option for deploying AI tools in real-world applications.

Ablation studies confirmed that each component of GAMIC was necessary. Both the introduction of graph neural networks and the use of SciBERT for encoding text contributed to the final performance. This work shows how graphical information can enhance the potential of large language models in the molecular sciences.

📜Title: GAMIC: Graph-Aligned Molecular In-context Learning for Molecule Analysis via LLMs 🌐Paper: https://aclanthology.org/2025.findings-emnlp.996.pdf 💻Code: Not provided

5. BIOARC: Redefining Biological Foundation Models with NAS, Surpassing DNABERT-2 with 1/20th the Parameters

The field of AI for Science often tries to apply the Transformer directly to DNA or protein sequences. The BIOARC paper offers a different take: generic Natural Language Processing (NLP) architectures are not the best solution for biological data.

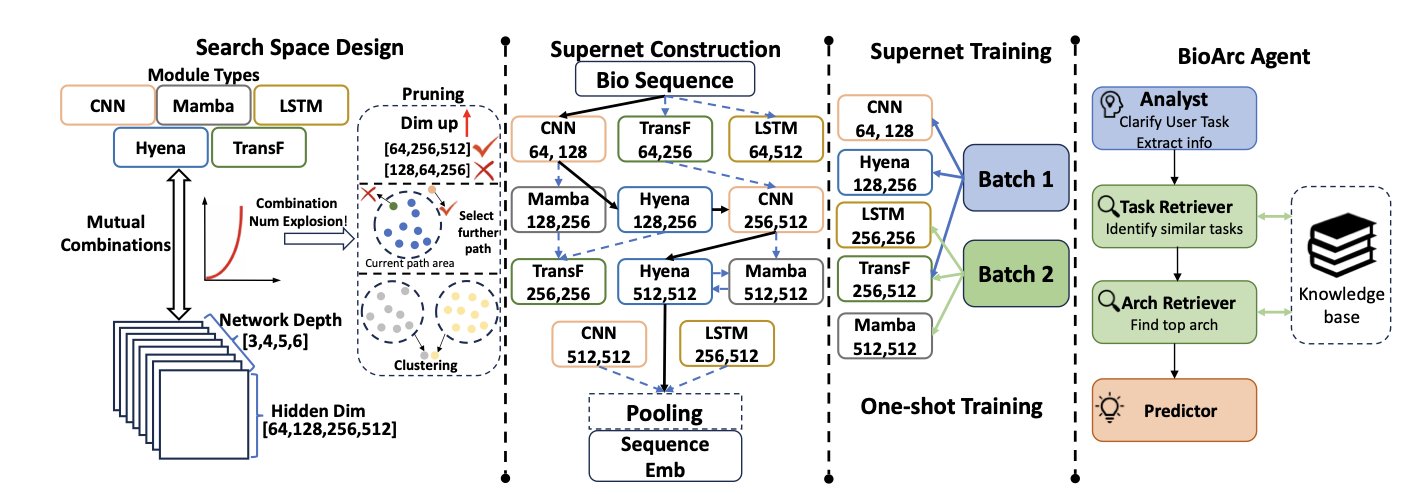

The researchers developed the BIOARC framework, which allows an algorithm to automatically “evolve” the optimal network structure.

Why redesign the architecture?

The “language” of biology follows the laws of physics and chemistry, which is different from the grammatical logic of human languages. BIOARC constructed a search space containing multiple modalities like DNA and proteins, like a huge library of candidate components.

The core technology is the Supernet. BIOARC uses a weight-sharing mechanism where all candidate subnetworks share the weights of a single “large network.” This is like testing different room layouts within the same building frame without having to rebuild the entire building each time, making large-scale exploration feasible.

In the face of data, large models can be a bit “bloated”

There is wasted parameter count and computational resources. The data shows that the model found by BIOARC has only 1/20th the parameters of DNABERT-2 and was trained for only 1/10th the steps, yet it outperformed it on biology benchmarks. A smaller model that fits the characteristics of biological data can beat a large model that was built by blindly stacking resources. This could greatly lower the barrier and cost for drug development institutions to deploy high-performance AI models.

It’s not just about the architecture, but also tokenization

BIOARC also took a deep dive into tokenization strategies. The optimal way to tokenize is highly coupled with the network architecture; there is no one-size-fits-all “best tokenization method.” The architecture, tokenization, and training strategy must be “jointly optimized.”

BIOARC Agent: your personal architecture designer

To make it easier to use, the BIOARC Agent allows users to input a task description (e.g., “predict protein solubility”), and it will automatically predict the best model architecture for that task based on its knowledge base, showing excellent performance on transfer learning tasks.

For AI in drug development, especially for sequence modeling tasks, maybe what’s needed isn’t hundreds of A100 GPUs, but a network architecture that understands biology.

📜Title: BIOARC: Discovering Optimal Neural Architectures for Biological Foundation Models 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.00283

6. Dissecting the Antibody AI Brain: Can We Use SAEs to Understand and Control New Drug Design?

Antibody drug discovery faces a common challenge. The antibody language models we use, like the p-IgGen model studied in this paper, can generate huge numbers of antibody sequences, but how they work is like a black box. We don’t know why they generate a specific sequence, which is a problem for drug development that requires precise and controllable design.

This paper tries to open that black box using Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs).

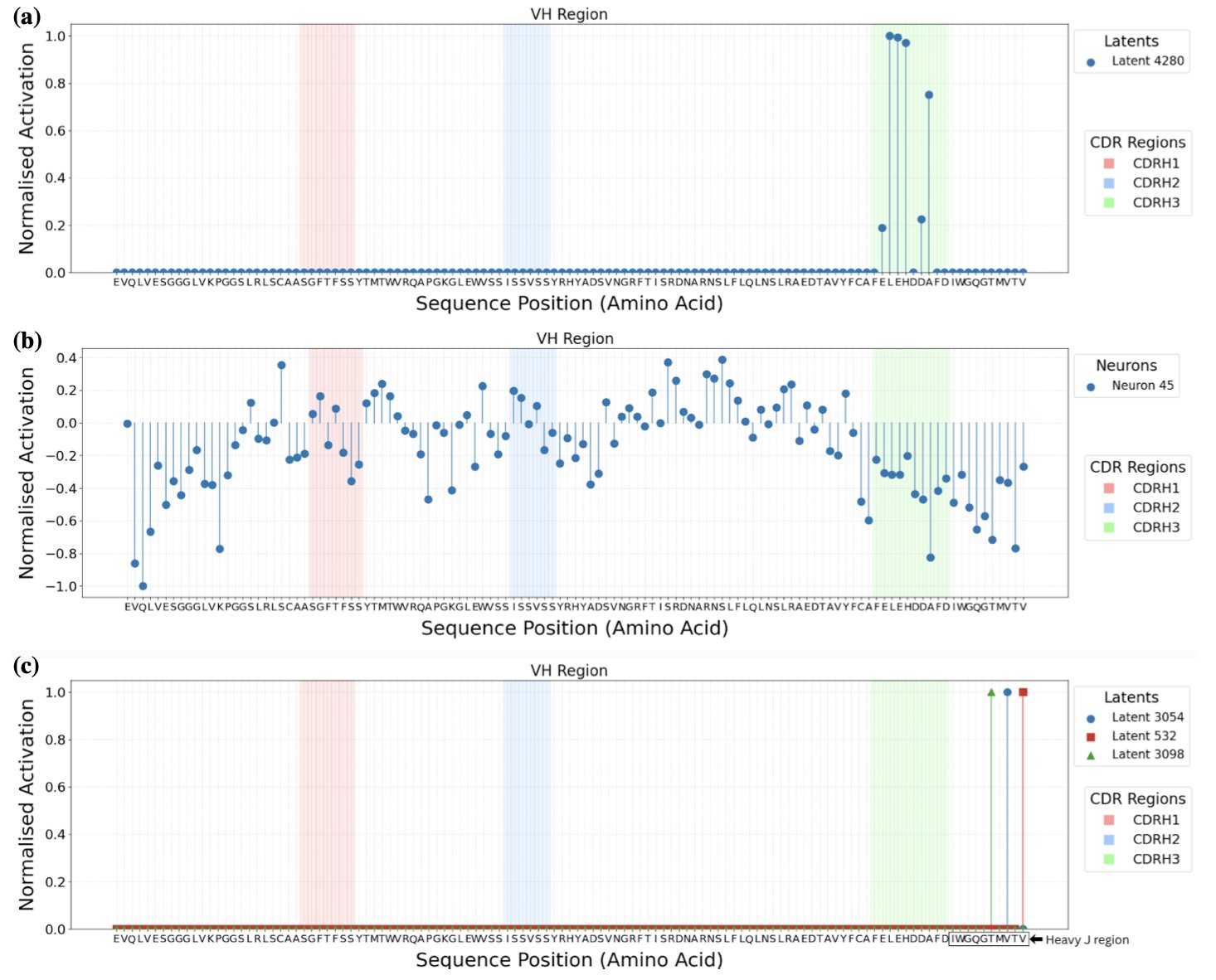

An SAE is like an efficient compression tool. It forces the model to describe a complex antibody sequence using just a few, highly refined “words” (i.e., features). To be able to decompress the information without any loss, the model must learn to capture truly meaningful biological concepts, like “a specific amino acid at a certain position” or “a certain type of structure.”

The researchers tested two types of SAEs.

The first was the TopK SAE, which was excellent at “explaining” things. It was able to find features that we could intuitively understand. For example, the activation of a certain feature strongly corresponded to the appearance of arginine at a specific position in the CDR-H3 loop. This gives us a glimpse into the AI’s “thought process.”

But then a problem arose. When we tried to manually activate this “arginine” feature to make the model generate sequences with arginine, the model didn’t always follow the instruction. This reveals a core dilemma in R&D: correlation does not equal causation. The appearance of a feature might be the result of arginine being present, not the cause. It’s like seeing that the ground is wet and concluding it just rained; but pouring water on the ground won’t make it start raining. This finding shows that AI interpretability is not so simple.

So, they tried a second tool, the Ordered SAE. This method was better at “controlling” the model’s generation. By activating the features it found, we can more reliably guide the model to produce the changes we want, which helps in generating antibody libraries with specific properties.

However, we can no longer understand these “controllable” features. They no longer simply correspond to a specific amino acid but might represent more abstract concepts, like “a hydrophobic surface suitable for binding to an antigen.” It’s like finding a button that makes a car go faster but not knowing whether it does so by increasing fuel injection or adjusting the turbocharger. We can use it, but we don’t know the principle behind it.

So, this work brings us to a fork in the road: we have a key that can “see” (TopK SAE) and a key that can “steer” (Ordered SAE), but they are not yet the same key. The industry’s ultimate goal is to find the feature that represents “high affinity,” and then directly enhance that feature to make the model consistently generate high-affinity antibodies.

This paper shows that there is a long road ahead to achieve this goal. It also points out a key bottleneck: we need more and higher-quality labeled data. Without enough data to tell the model which sequences are good and why they are good, no matter how many features we find, we are still just fumbling in the dark.

📜Title: Mechanistic Interpretability of Antibody Language Models Using SAEs 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.05794