Table of Contents

- The HSADab database gets a major upgrade, using AI to predict the binding affinity of a chemical structure to human serum albumin.

- QligFEP v2.1.0 makes free energy calculations cheaper and faster by simulating only the critical protein binding pocket, opening the door for large-scale use.

- Researchers designed a Geometric Graph U-Net that improves the recognition of 3D protein folding patterns by modeling a protein’s hierarchical structure, from local to global.

- A new method called PredPPI-GReMLIN achieves high-accuracy protein interaction predictions by modeling interfaces as bipartite graphs and mining them for conserved structural patterns.

- In molecular graph self-supervised learning, predicting chemically meaningful motifs boosts model performance more than designing complex masking strategies, especially when paired with a Graph Transformer.

- The new FoldBench benchmark shows that while models like AlphaFold 3 have made huge strides, reliable prediction in key areas of drug discovery, like antibody design and nucleic acid targeting, remains a distant goal.

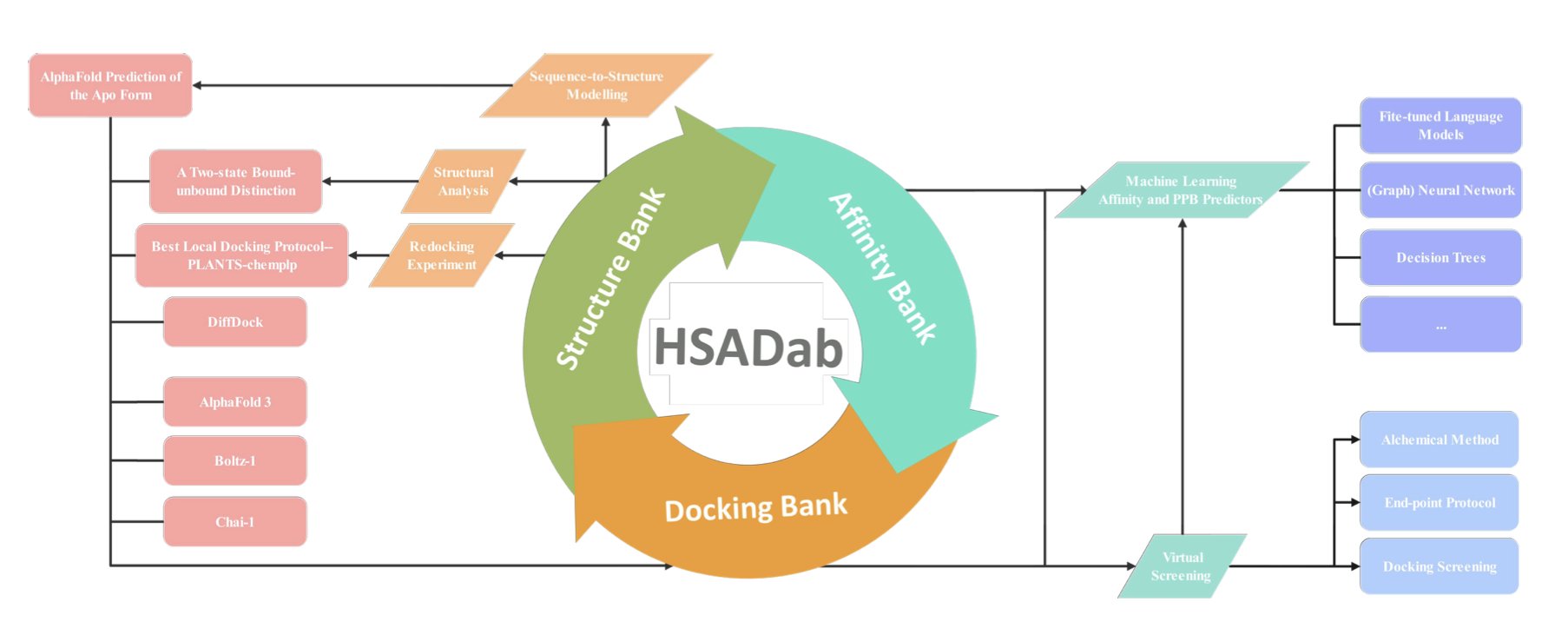

1. AI Reshapes the HSA Database: Predicting Drug-Plasma Protein Binding

Human Serum Albumin (HSA) is the blood’s universal taxi, responsible for transporting small-molecule drugs. If a drug binds too tightly, it won’t be released to do its job. If it binds too loosely, it gets cleared from the body too quickly. Predicting this Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) has always been a challenge in drug development, traditionally relying on experience and tedious experiments.

This update to the HSADab database deeply integrates AI. Now, a user can just input a SMILES string, and the system predicts the molecule’s binding affinity to HSA and its PPB rate. This end-to-end prediction can save a lot of testing time during early-stage screening.

A significant advance is the addition of structural data. Since experimentally determined crystal structures of these complexes are rare, researchers used AlphaFold3 and DiffDock to generate a docking library of over 2,000 complexes. It’s like having a snapshot of how each drug molecule sits inside the “taxi,” showing us which pocket it occupies and providing a basis for rational molecular optimization.

HSA’s structure isn’t rigid. Molecular simulations have found that HSA has both “bound” and “free” conformations. As a drug approaches, the protein undergoes a significant conformational change to envelop it. This structural flexibility is something that older, static docking methods could not capture.

The research also offers a practical conclusion on tool selection. While the AutoDock series is widely known, in the specific case of HSA, the PLANTS software performed better.

These tools are now integrated into the hsadab.cn website. For medicinal chemists, it turns complex calculations into simple online operations, helping to weed out molecules with poor drug-likeness at the very start of a project.

📜Title: Human Serum Albumin: AI-powered Modelling of Binding Affinities and Interactions 🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-mx3fh-v3 💻Code: http://www.hsadab.cn

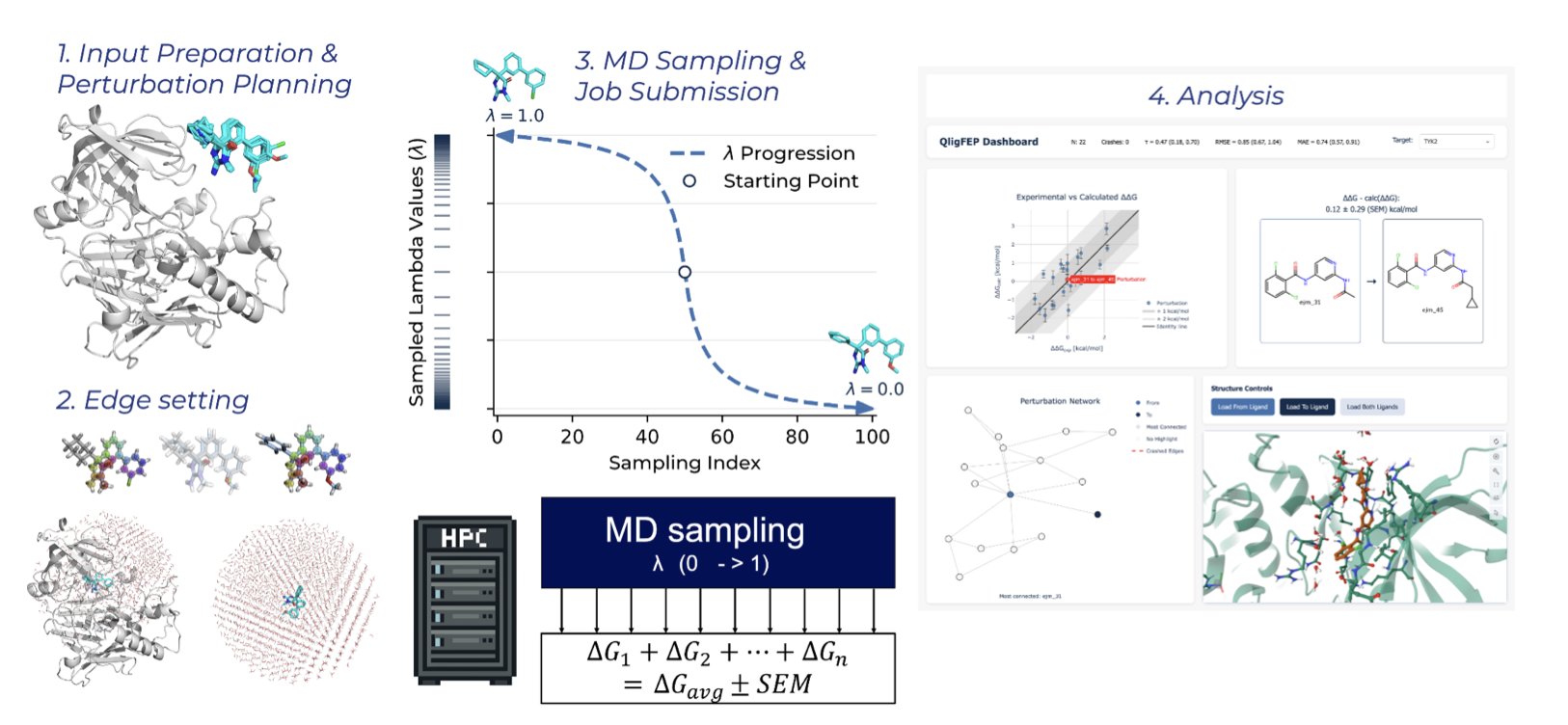

2. QligFEP v2.1: A Tool to Make Free Energy Perturbation Calculations Accessible

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) is a highly accurate prediction tool in drug discovery, but its high computational cost and long run times have limited its use.

The open-source platform QligFEP aims to solve this problem. Traditional FEP calculations place a protein-ligand complex in a huge “water box” for simulation. Most of the computing power is spent on water molecules that have little to do with the binding interaction, which is wasteful.

QligFEP introduces Spherical Boundary Conditions (SBC), which act like a spotlight, focusing the computation on a spherical region centered on the binding pocket. The area outside the sphere is handled with a simplified approach.

This method reduces the amount of calculation needed and speeds things up. According to the paper, a single perturbation calculation takes less than two hours on a standard cluster. The cost on Amazon Web Services (AWS) is less than $1 per edge. This makes FEP technology accessible to ordinary academic labs, not just a few well-funded institutions.

To verify its accuracy, researchers ran benchmark tests on 639 ligand transformations across 16 common industrial protein targets. The results showed that QligFEP’s prediction accuracy is on par with expensive commercial software (like Schrödinger’s FEP+) and other open-source tools. The simplification did not introduce systemic bias.

QligFEP is also easier to use. It automates steps like ligand mapping and perturbation network generation. Users just need to provide the ligand and protein structures, which simplifies the workflow and facilitates high-throughput virtual screening.

With its flexible internal restraint algorithms, QligFEP can also handle complex chemical structure transformations like ring openings and closings, tackling real-world problems in drug development.

In the future, the development team plans to improve its stability for complex chemical transformations and develop GPU and cloud-native versions to further increase computational efficiency.

By improving the algorithm, QligFEP lowers the barrier to FEP calculations while maintaining accuracy. Making this technology more accessible should help speed up the process of new drug discovery.

📜Title: Doing More with Less: Accurate and Scalable Ligand Free Energy Calculations by Focusing on the Binding Site 🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-x3r3z-v3

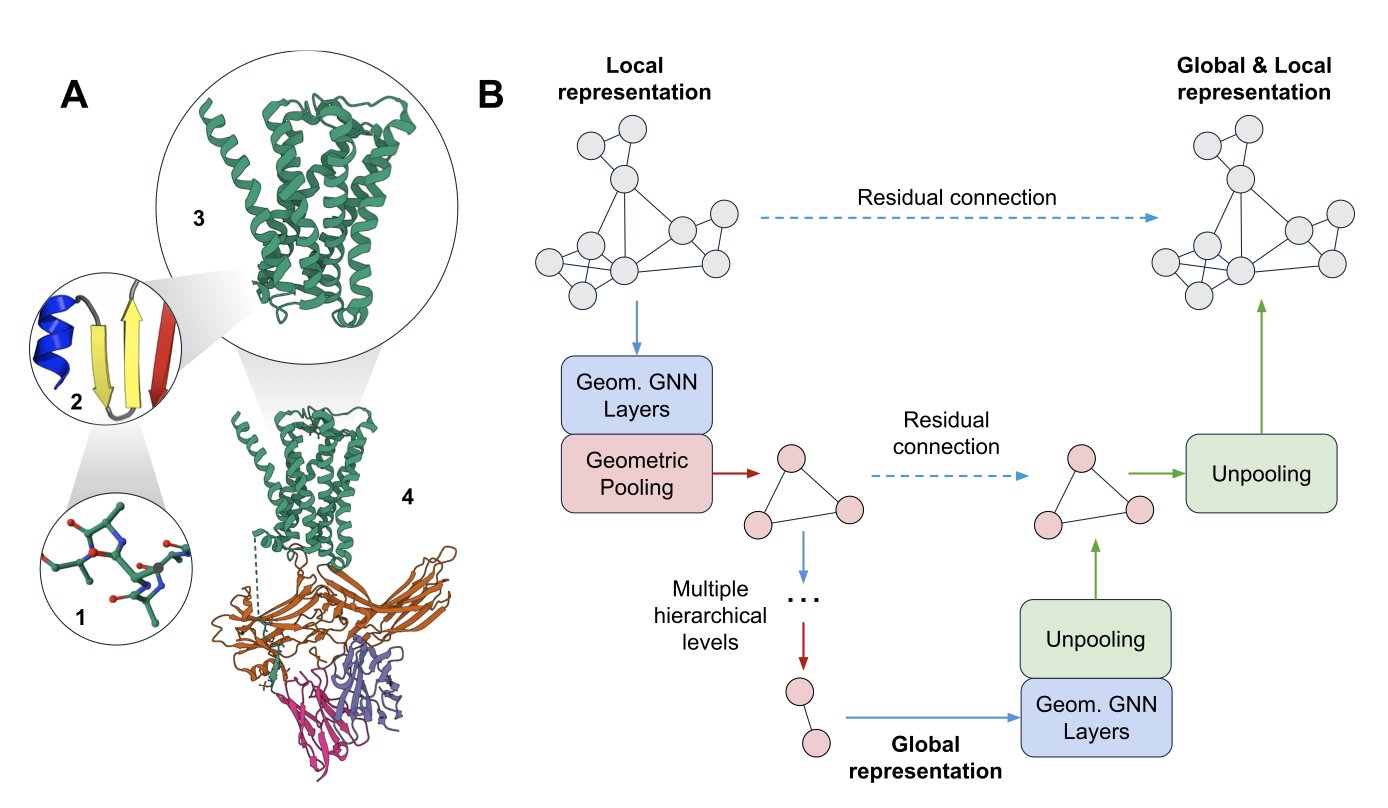

3. Geometric Graph U-Nets: Understanding Multi-Scale Protein Structure Like Building with LEGOs

Scale is everything in protein structure analysis. The orientation of a single amino acid’s side chain can determine if it binds to a drug molecule. But how the α-helix containing that amino acid stacks with other secondary structures determines the protein’s overall function. Drug development needs to see both the “trees” (local atomic interactions) and the “forest” (overall domain folding), but current computational tools struggle to do both.

Standard Geometric Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are like a magnifying glass that only works up close. They excel at capturing local geometric relationships like bond lengths and angles, making them great for understanding a small drug-binding pocket. But if you want to know where that pocket is in the entire protein, or how the protein’s overall shape changes affect it, these models fall short. They lack a top-down, global perspective.

This paper gives GNNs a “zoom lens.”

The authors introduced a new model called a Geometric Graph U-Net. The U-Net approach comes from image processing: first, you use “downsampling” to progressively compress a high-resolution image into a smaller, blurrier one to capture the core global features. Then, you use “upsampling” to restore the details, guided by those global features, to get a precise final result.

The researchers applied this idea to protein structures. Their model first “coarsens” the protein’s atomic graph. You can think of this as bundling several neighboring amino acid residues into a single “super-node,” creating a more macroscopic, lower-resolution view of the protein. By repeating this process, the model sees the protein at the atomic scale, then the secondary structure scale, and finally the domain scale, gaining a global understanding.

Next, the model reverses the process with “refining.” It passes the information learned at the macro scale back down to the micro scale, layer by layer, so each atom becomes aware of its global environment. This gives the model both local detail and a global view at the same time.

The core of this “coarsening” and “refining” process is two new types of pooling layers: Point Pooling and Sparse Pooling. Pooling is a common technique in GNNs for downsampling, but previous methods often ignored 3D geometric information or were too computationally expensive. These new tools efficiently aggregate meaningful local geometric information and connect seamlessly with existing GNN layers. It’s like finding the perfect LEGO connectors that let you build quickly while keeping the structure stable.

How well does the model perform? On a protein fold classification task, the Geometric Graph U-Net outperformed baseline models that focused only on local or only on global features. This shows that the “see the forest, then the trees” strategy works.

The authors also proved the superiority of this multi-scale architecture theoretically. They extended a test called the Geometric Weisfeiler-Leman (GWL) test to show that the pooling operation can enhance the model’s ability to distinguish between different graphs (its “expressive power”). This theoretically ensures that the model doesn’t lose critical structural information during the “coarsening” process.

This work opens up a new path for designing more powerful models for protein structure representation learning. For drug development, this could lead to more accurate tools for predicting a drug’s off-target effects, understanding the long-range mechanisms of allosteric regulation, or even designing entirely new functional proteins from scratch.

📜Title: Multi-Scale Protein Structure Modelling with Geometric Graph U-Nets 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.06752v1

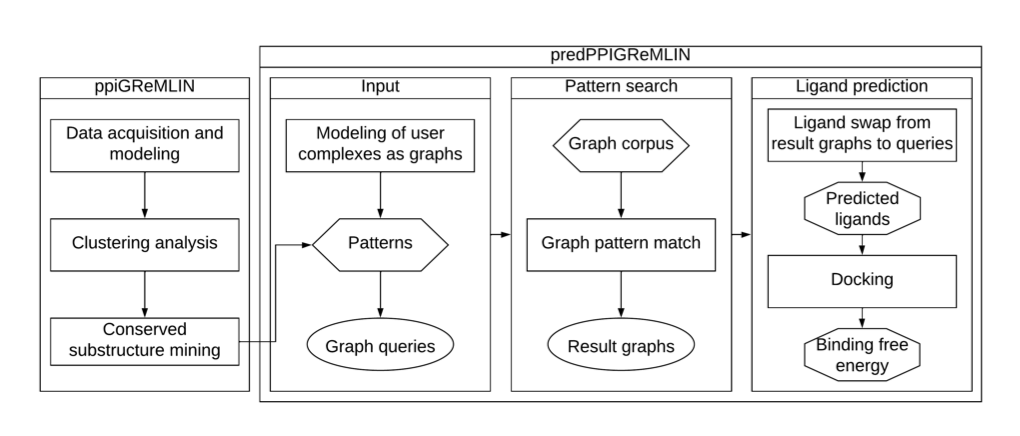

4. A New Approach for Graph Networks: Mining Protein “Handshake” Patterns to Predict Drug Targets

Predicting Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) is a central problem in drug discovery. Relying on sequence information alone doesn’t provide enough detail. What determines if two proteins will bind is the precise atomic match at their contact interface, including shape, charge, and hydrophobicity.

A new tool called PredPPI-GReMLIN offers a new way to think about this.

Drawing the “Handshake” as a Graph

The researchers treat the contact interface of two proteins as a bipartite graph. Imagine a dance party. On one side of the graph are all the amino acid residues on the surface of protein A. On the other side are the residues on the surface of protein B. If two residues interact—say, by forming a hydrogen bond or a hydrophobic contact—a line is drawn between them.

This method views the interface as a precise network of relationships, capturing the “dialogue” between atoms. This graph contains specific chemical and physical information that goes far beyond what sequence data can offer.

Mining for Common “Handshake” Patterns

Next, the researchers developed a graph-searching algorithm to find recurring, conserved interaction patterns in a large database of protein complexes.

This process is like a linguist studying conversations to find common phrases. PredPPI-GReMLIN learned from thousands of known protein binding modes to build a library of patterns. When it encounters a new pair of proteins, it checks whether their interface matches any of the known patterns in its library to predict if they will interact.

How Does It Perform?

On classic test sets like CAMP and Yeast, the method’s precision, recall, and F1 score were all over 97%.

In a more complex multi-class classification task, where the model had to distinguish between interaction types like hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and hydrophobic interactions, its accuracy reached 57.74%. While that number might not seem high, accurately distinguishing between interaction types is extremely difficult. This result is quite good and shows the model understands what kind of relationship exists. The model also incorporated features like Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA), which improved its understanding of the chemical environment and boosted its predictive power.

A Real-World Test on SARS-CoV-2

The tool was validated on an important drug target: the interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and the human ACE2 receptor.

The researchers used PredPPI-GReMLIN to predict small-molecule ligands that could disrupt the Spike-ACE2 interaction, then verified them with molecular docking. The predicted ligands had a much better binding energy with the Spike protein than random molecules (p = 5.1×10⁻⁹), showing that the results were statistically significant.

This demonstrates that the graph patterns found by PredPPI-GReMLIN correspond to real physical and chemical principles and can be used to guide effective drug design and screening.

The tool’s code and data are publicly available, so researchers can use and extend it for their own projects. This approach of starting from structural details to find general rules provides a new direction for PPI prediction and drug design.

📜Title: PredPPI-GReMLIN: Prediction of Protein-Protein Interactions through Mining of Conserved Bipartite Graphs 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.03.692055v1 💻Code: https://github.com/morufwork/predPPIGReMLIN.git

5. Molecular Graph Pre-training: Predicting Chemical Motifs Matters More Than Masking Design

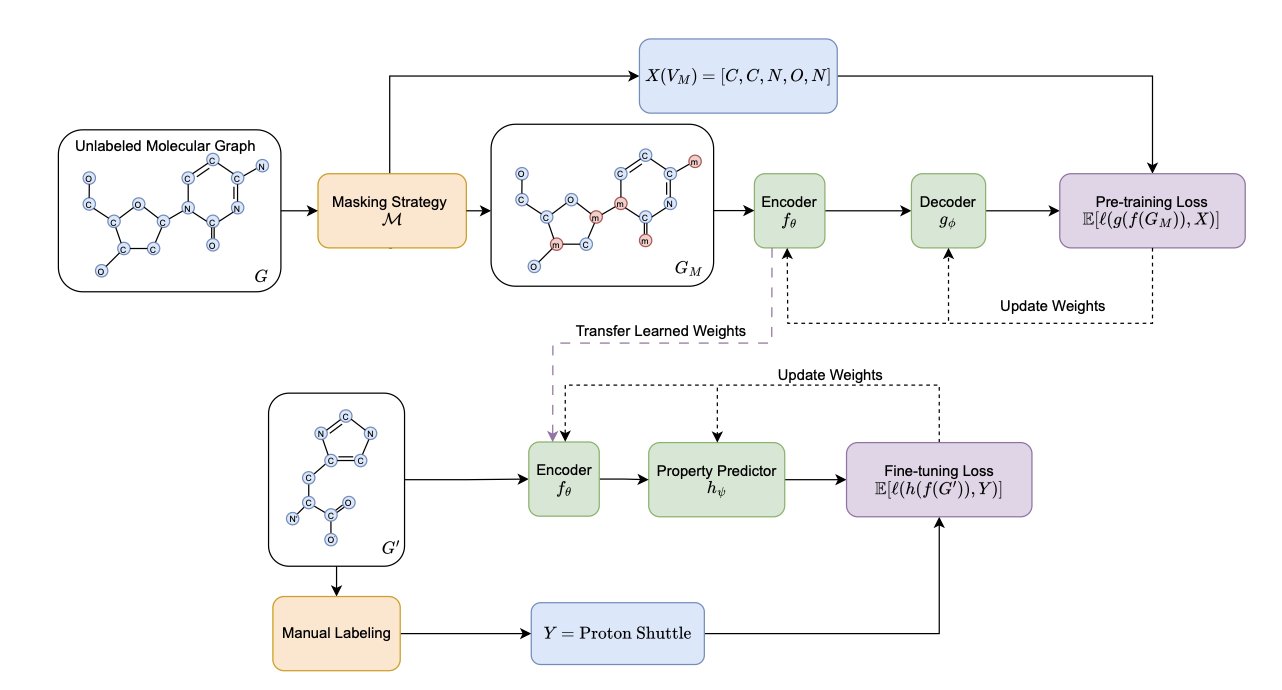

Molecular representation learning relies heavily on Self-Supervised Learning (SSL). A common approach is like a “fill-in-the-blank” game: part of a molecule’s information is hidden (masked), and the model has to predict what’s missing. Much research has focused on designing cleverer masking strategies to help the model learn better.

This work systematically evaluated this problem and found that past efforts might have been misdirected. Extensive experiments show that carefully designed, complex masking strategies do not offer a consistent advantage over the simplest random masking on downstream tasks. Investing too much effort in how to mask information yields little return.

The key to improving model performance is what we ask the model to predict.

The traditional approach is to have the model predict the masked single atoms. This is like teaching a child a language by only having them guess letters. They might learn to spell, but they won’t easily understand words or sentences.

This work proposes a new idea: upgrade the prediction target from single atoms to chemically meaningful “motifs.” Motifs are the functional units of a molecule, like a benzene ring or a carboxyl group, which determine its core chemical properties. Asking the model to predict a whole motif is like asking a child to guess a complete word. This pushes the model to understand the underlying rules and context of chemistry.

From a chemist’s point of view, this idea is intuitive. A molecule’s activity, toxicity, and other properties are directly related to these functional motifs. If a model can learn to recognize and reconstruct motifs, it can gain a deeper understanding of the molecule. The researchers used tools like Mutual Information to prove mathematically that motif labels have a stronger statistical correlation with molecular properties.

A good learning task also needs a powerful model. The study found that Graph Transformers benefit more from the motif prediction task than traditional Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs). The attention mechanism in a Graph Transformer allows the model to dynamically focus on different parts of the molecule during prediction, which is crucial for understanding a motif’s role in the overall structure. It’s like giving a good student a better textbook—their learning improves more significantly.

This work provides a clear direction for molecular pre-training: instead of spending energy designing complex masking strategies, it’s more effective to focus on defining chemically meaningful prediction targets and pairing them with a suitable model architecture.

📜Title: Self-Supervised Learning on Molecular Graphs: A Systematic Investigation of Masking Design 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.07064v1

6. The FoldBench Benchmark: A High-Stakes Exam for AI Structure Prediction

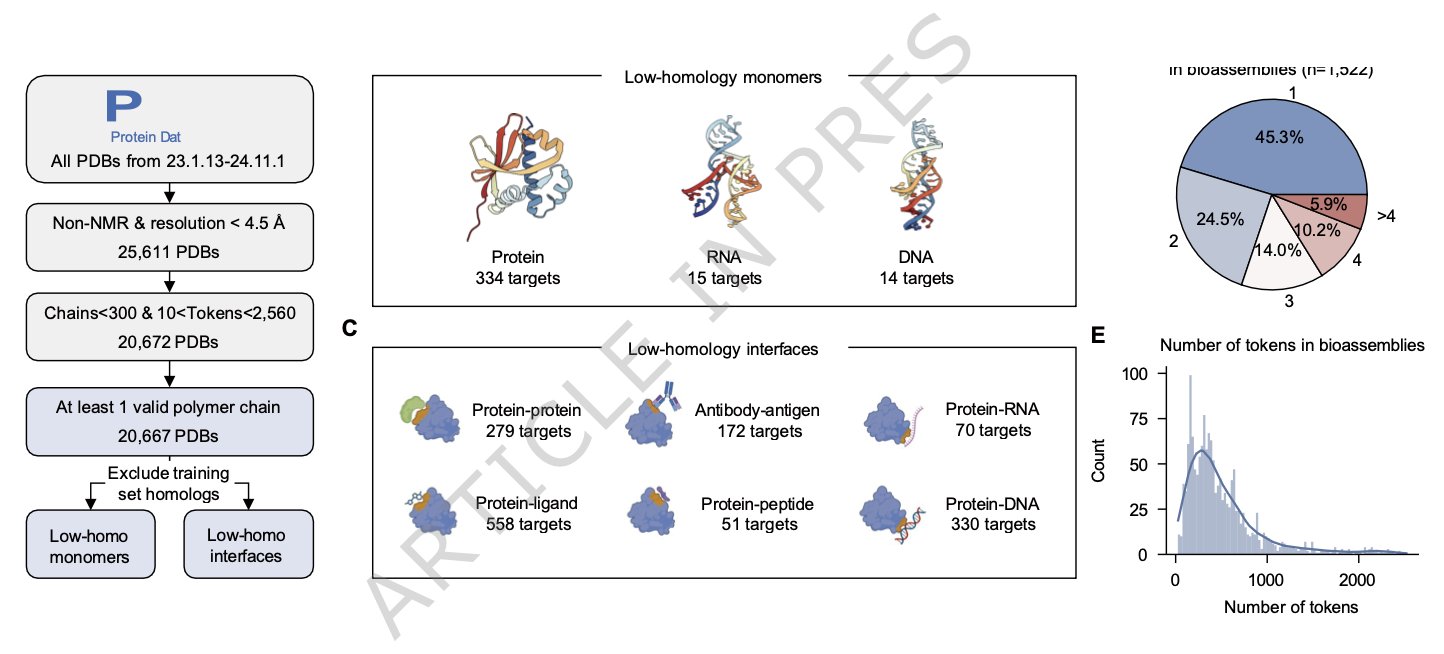

AI models like AlphaFold are frequently in the news for their breakthroughs in structure prediction. But drug developers on the front lines are always asking: how useful are these models in real, complex R&D scenarios? A paper in Nature Communications on FoldBench provides a more realistic answer.

FoldBench is like a high-stakes “final exam” for AI models, tailored for drug discovery. Previous benchmarks were often single-task tests, like predicting the structure of a single protein. But drug discovery deals with complex systems: small molecules binding to proteins, antibodies recognizing antigens, and the mechanisms of RNA-targeting drugs. FoldBench covers these real “application problems” with nine categories of tasks involving proteins, nucleic acids, small-molecule ligands, and their interactions.

The test results show that AlphaFold 3 is the best-performing model today, leading in several categories and demonstrating the progress AI has made.

But the key details reveal the models’ limits, and these are the details that determine success or failure in drug development.

First is antibody-antigen interaction. The critical parts of an antibody are its highly variable Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs). These loops are flexible and determine how accurately an antibody recognizes its antigen. The FoldBench tests show that current models are not good enough at predicting the structure of these CDR loops. For antibody drug development, AI cannot yet replace high-throughput screening and structural biology experiments. It can only provide a rough initial conformation, and relying on it for precise antibody design is too risky.

Second are allosteric systems. Allostery is like a remote control; many drugs work this way to indirectly regulate a target’s activity, often causing subtle but critical conformational changes in the protein. AI models face a huge challenge in predicting these kinds of conformational changes caused by small molecules. If they can’t see these subtle shifts, their role in early-stage allosteric drug discovery is limited.

Third is nucleic acid structure. RNA-targeting drugs are a hot area right now, but RNA structures are more flexible than proteins and harder to predict. The FoldBench data shows that AlphaFold 3’s scores for predicting nucleic acid structures are much lower than its scores for single proteins. The root cause is the scarcity of high-quality nucleic acid structural data for training.

A deeper problem is the models’ generalization ability. When the chemical structure of a test molecule (especially a small-molecule ligand) is very different from the training set, prediction accuracy drops sharply. This suggests the models are more like students “cramming for a test” from a known question bank rather than truly understanding the underlying principles of physics and chemistry. Since innovative drug discovery is all about predicting entirely new molecules, if AI is unreliable here, its value is severely diminished.

The arrival of FoldBench provides a valuable “calibration tool.” It tells researchers where the current boundaries of AI are and where they need to be cautious. It also points the way for model developers: shift the focus from single proteins to solving these real-world problems.

📜Title: Benchmarking all-atom biomolecular structure prediction with FoldBench 🌐Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-49483-x