Table of Contents

- The DiffDock-L model, fine-tuned on a specific dataset, doubled its success rate in predicting the binding poses of difficult allosteric kinase inhibitors, offering a new way to solve these docking problems.

- Researchers used sparse autoencoders to open the “black box” of single-cell foundation models, allowing us to understand and correct what the AI learns.

- CrossPPI integrates protein structure graphs and sequence features using a Transformer cross-fusion module, significantly improving the accuracy of binding affinity predictions.

- For the first time, an AI has not only generated DNA sequences but also designed a complete, functional plasmid that works in living cells.

- The GRASP framework combines multi-agent and graph reasoning technologies, allowing scientists to build and modify complex quantitative systems pharmacology models using natural language, which greatly lowers the programming barrier.

- OMTRA uses a single generative model with flow matching to handle de novo drug design, molecular docking, and conformation generation at the same time. The model performs well, but the benefits of multi-task learning were limited.

1. Fine-tuning DiffDock to Solve Allosteric Kinase Docking

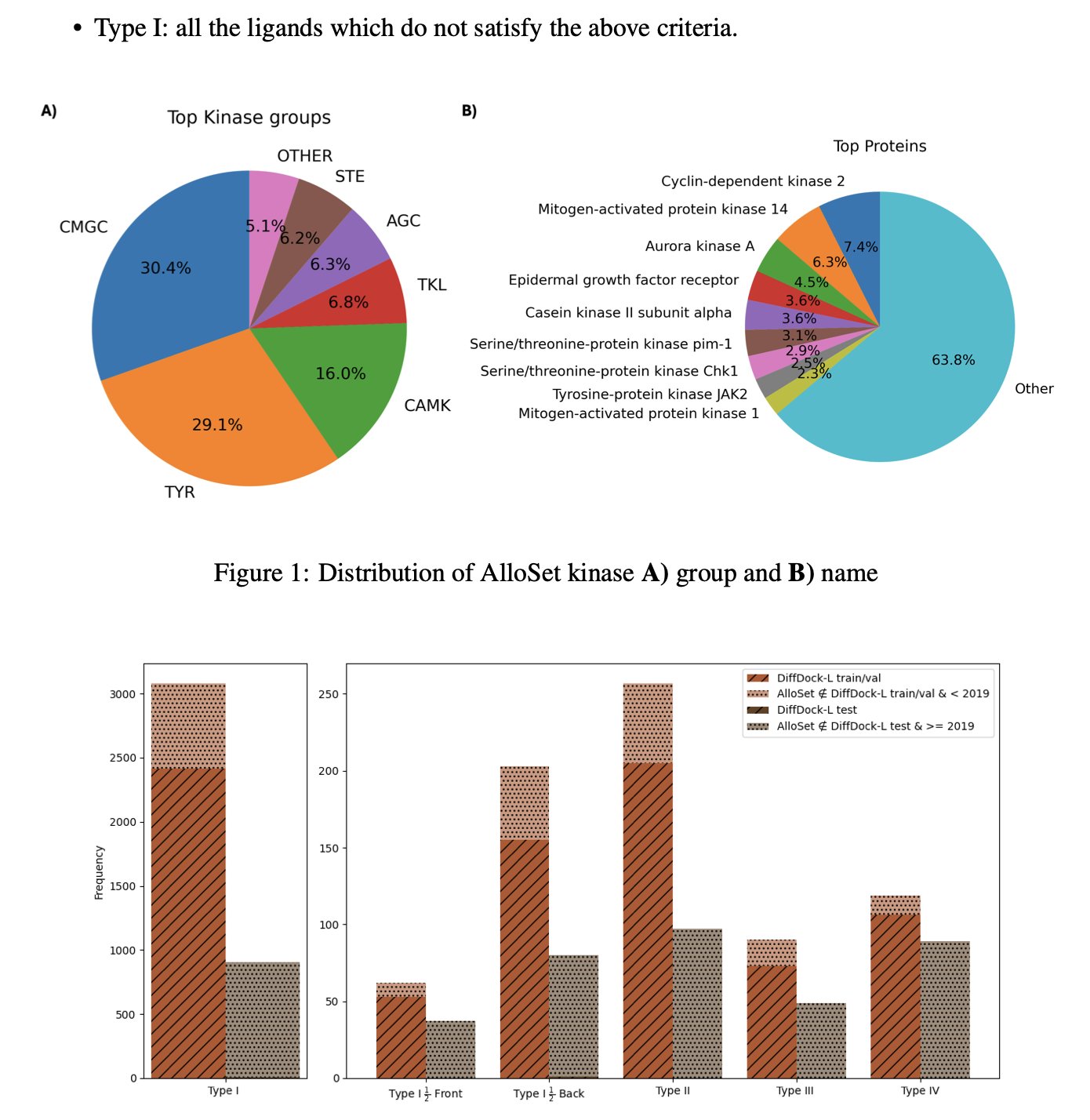

Kinases are common targets in drug development, but past research has mostly focused on the ATP binding pocket. This pocket is structurally conserved, making the design of inhibitors (Type I/II) straightforward. Now, allosteric sites are getting more attention.

Allosteric sites can achieve higher selectivity and even overcome drug resistance. But these sites have diverse shapes and are often shallow and hydrophobic, unlike the deep ATP pocket. Traditional molecular docking software struggles to provide reliable predictions for this kind of open terrain.

To solve this, researchers took a practical approach: they used a generative AI docking model, DiffDock-L, and gave it specialized training.

The first key step was preparing the training data. They collected high-quality crystal structures of kinase-allosteric inhibitor complexes from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to build a dedicated dataset called AlloSet. High-quality data is the foundation for a model’s performance.

DiffDock works by progressively “denoising” a ligand’s pose, starting from a random position to generate the most plausible binding conformation. Because it has seen so many examples of the ATP pocket during training, the model has a bias toward placing inhibitors in deep pockets.

To correct this bias, the researchers used a clever fine-tuning strategy called tr/rot_only. This strategy only adjusts the molecule’s translation and rotation, temporarily freezing its internal rotatable bonds (torsion).

It’s like parking a car. First, you drive the car to the general area of the parking spot (translation and rotation). Then, you make small adjustments to the steering wheel to park it perfectly (adjusting internal conformation). This “big picture first, details later” approach prevents the model from getting stuck in a locally optimal conformation too early, helping it find the correct general area of the allosteric site first.

The results were significant. For Type III allosteric inhibitors, after fine-tuning with the tr/rot_only strategy, the proportion of correct poses with a Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of less than 2Å in the top 10 predictions increased from the baseline model’s 18% to 36%. The success rate doubled.

This work shows that in AI-assisted drug design, “expert models” tailored for specific target families or binding modes can be more effective than general-purpose models. By fine-tuning a “generalist” model on a small, high-quality dataset, it can be quickly trained to become a “specialist” for solving a specific problem.

For drug developers, this method could lead to faster, more reliable molecular docking results when working on new allosteric targets, guiding subsequent structural optimization and synthesis.

📜Title: Fine-Tuning DiffDock-L for Allosteric Kinase Docking 🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-b8k76 💻Code: https://github.com/electrojustin/DiffDock-Fine-Tune

2. The AI Black Box Is Opened: Decoding the Inner Workings of Single-Cell Models

Large models in single-cell analysis, like scGPT, are powerful, but how they work internally is a black box. The models can give accurate cell classifications and annotations, but they can’t explain the basis for their judgments. In high-stakes fields like drug development, this lack of interpretability creates a trust issue. A single wrong judgment could lead to losses of millions of dollars.

Research by Pedrocchi et al. offers a new way to solve this problem. They found a way to make the black box “speak.”

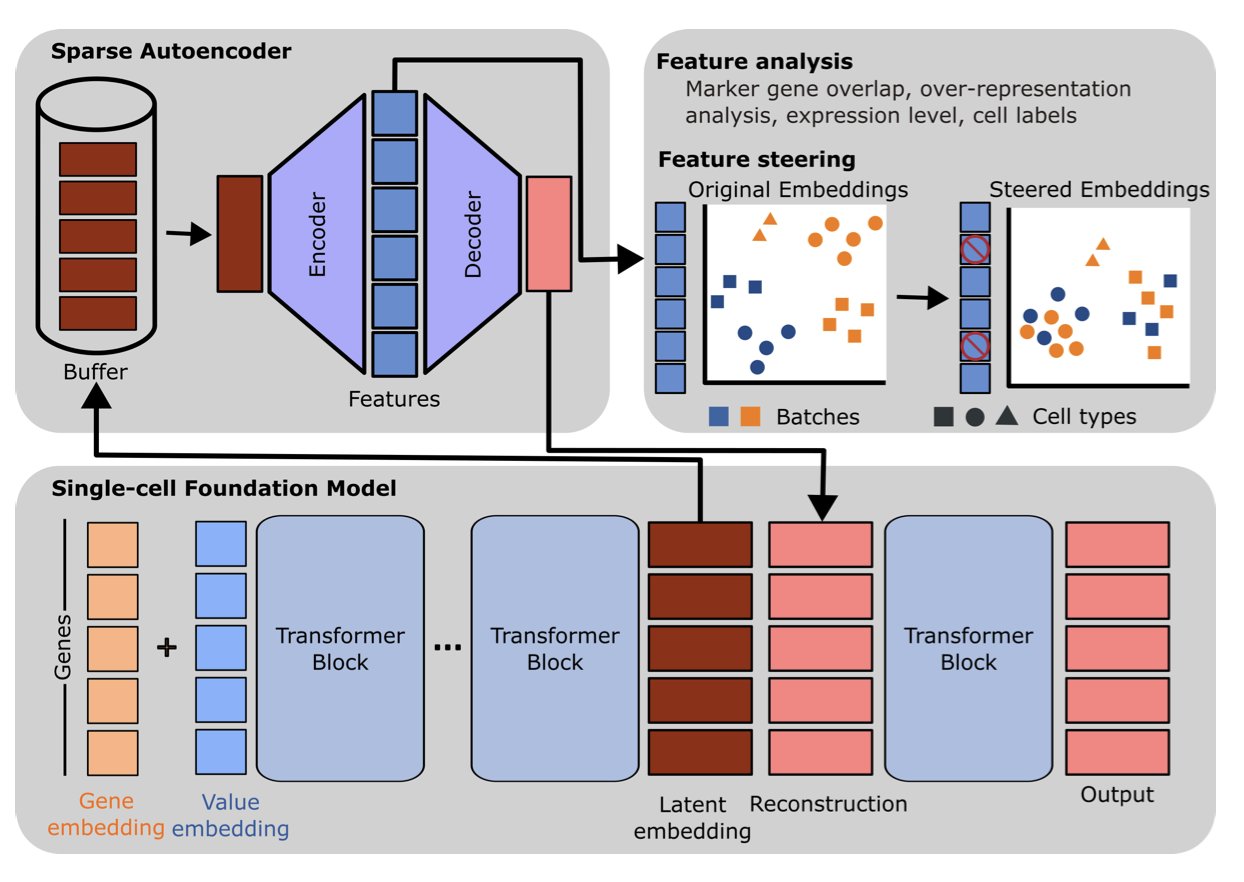

The core tool they used is the Sparse Autoencoder (SAE), which can be thought of as an efficient “information compressor.” When a Single-cell Foundation Model (scFM) processes data, it generates complex high-dimensional vectors internally, known as the model’s “hidden representations.” These vectors contain a mix of useful biological signals and useless technical noise.

An SAE works by taking these complex hidden representations, forcing them to be compressed into a limited set of highly concentrated “features,” and then trying to reconstruct the original representations from these features. This process forces the SAE to learn the most essential and representative patterns in the data.

The team applied SAEs to two major models, scGPT and scFoundation. They found that many of the features extracted by the SAEs corresponded directly to clear biological concepts. For example, one feature was activated only when gene expression profiles related to T cells appeared, representing “T-cell identity.” Another feature corresponded specifically to a metabolic pathway. This shows that the model learned real biological knowledge, not just unexplainable statistical correlations.

These features are causal. The researchers identified a feature representing the “batch effect”—a common source of technical noise in single-cell experiments. They performed a kind of “neurosurgery” by manually setting the activation value of this feature to zero inside the model, successfully removing the noise signal. The results showed that the batch effect was eliminated from the model’s output data, and data from different batches merged together better.

This is like an audio engineer identifying and removing the hum of an air conditioner from a recording, leaving only the clear human voice. It shows we can not only diagnose problems with the model but also directly correct them.

The study also found that a model’s training method and architecture determine how it learns. Different models might both be able to perform cell annotation tasks, but their internal “thought processes” can be completely different. This reminds us that understanding a model’s internal mechanisms is important for selecting and optimizing it. We can’t just treat it as a plug-and-play tool.

The research also pointed out the limitations of current models. An scFM can identify the same cell type across different datasets but often fails to form a single, universal concept for it. For example, macrophages from one study and macrophages from another might be encoded as two slightly different features inside the model. This indicates that the model’s ability to generalize still needs improvement.

This study provides an effective set of methods for analyzing and manipulating large single-cell models, transforming us from model users into developers who can “talk” with the model. In the future, this kind of interpretability could help build more reliable and controllable AI tools for drug target discovery and clinical translation.

📜Title: Sparse Autoencoders Reveal Interpretable Features in Single-Cell Foundation Models 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.22.681631v1

3. CrossPPI: Fusing Structure and Sequence to Accurately Predict Protein Binding Affinity

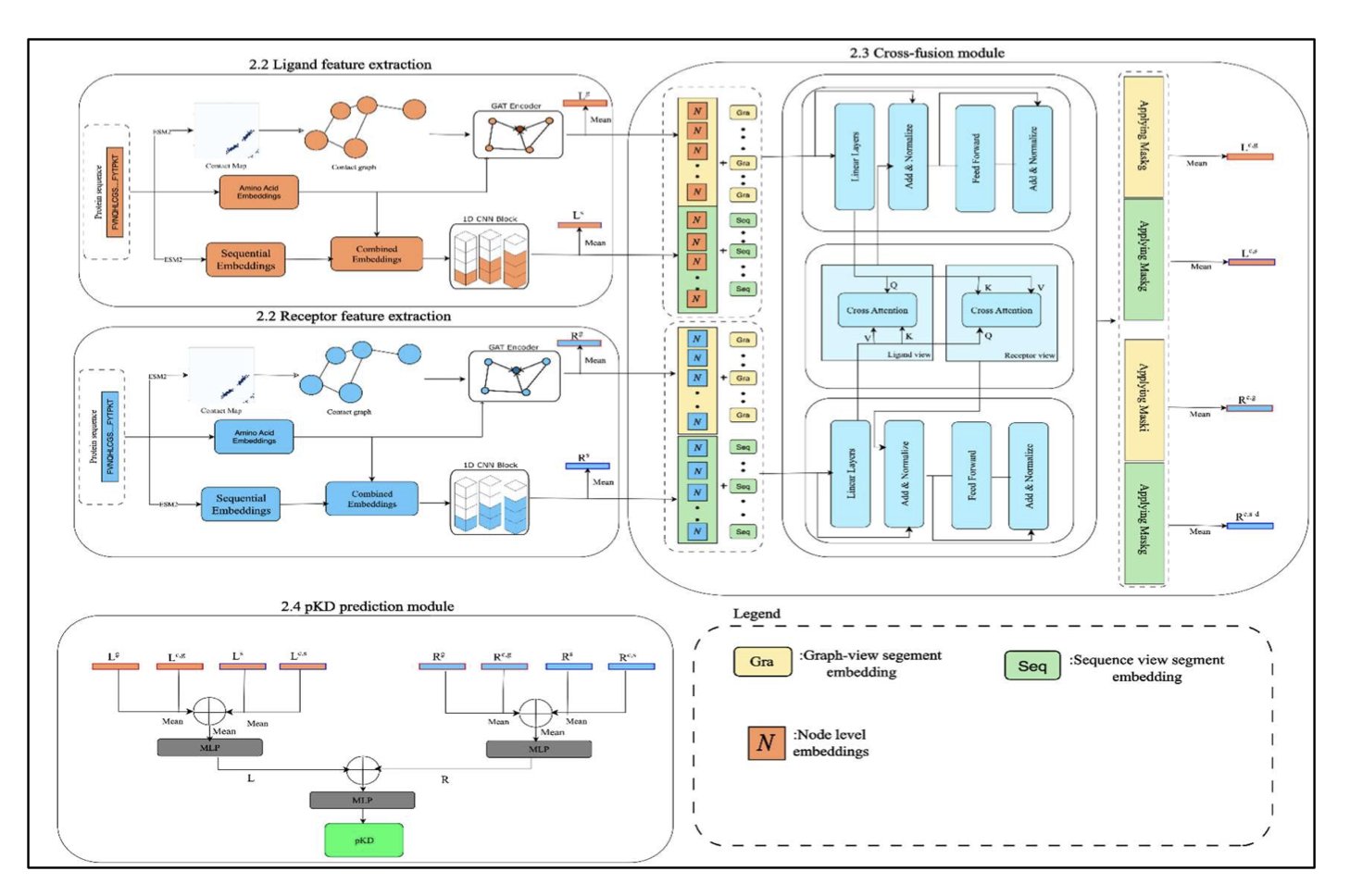

In drug development, it’s relatively easy to predict if two proteins will “meet,” but determining how tightly they “bind” (binding affinity) is key to making a successful drug. Current tools are often limited by a single perspective: looking only at the sequence is fast but lacks spatial context, while looking only at the 3D structure is accurate but limited by the scarcity of crystal data. CrossPPI solves this problem by directly fusing structural and sequence features.

How It Works The authors designed a Transformer-based cross-fusion module. This is like assembling a model kit by looking at both the instruction manual (sequence features) and the parts diagram (structural features). The model uses Graph Attention Networks (GATs) to parse the protein’s spatial geometry and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to extract sequence patterns.

The core of the model is “interaction.” Sequence and structural information are deeply fused in the Transformer layers. This allows the model to capture the complex, nonlinear effects of sequence mutations on the 3D spatial charge distribution. The inclusion of ESM2 embeddings and Contact Maps is like equipping the model with a “brain” pre-trained on massive amounts of data, deepening its understanding of protein context.

Performance On an independent test set of 300 protein-protein pairs, CrossPPI performed well. Its Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) was 0.7616, Spearman Correlation Coefficient (SCC) was 0.7644, and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) was down to 1.2869. In the noisy field of affinity prediction, this result confirms the model’s robustness.

Industry Value For Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD), CrossPPI’s modular design is a significant advantage. Its architecture is not a closed black box. In the future, the ESM2 module can be replaced as protein language models evolve, continuously improving accuracy. This flexibility is useful for virtual screening, PPI site prediction, and de novo protein design. It can effectively filter out “false positive” molecules before wet-lab experiments, reducing development costs.

📜Title: CrossPPI: A Cross-Fusion Based Model for Protein–Protein Binding Affinity Prediction 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.25.690371v1

4. AI Designs a Plasmid from Scratch, Validated in Living Cells for the First Time

In synthetic biology, designing a completely new plasmid backbone from scratch is hard. The usual approach is to modify an existing template. Now, researchers have tried letting an AI design one from the ground up, and they succeeded.

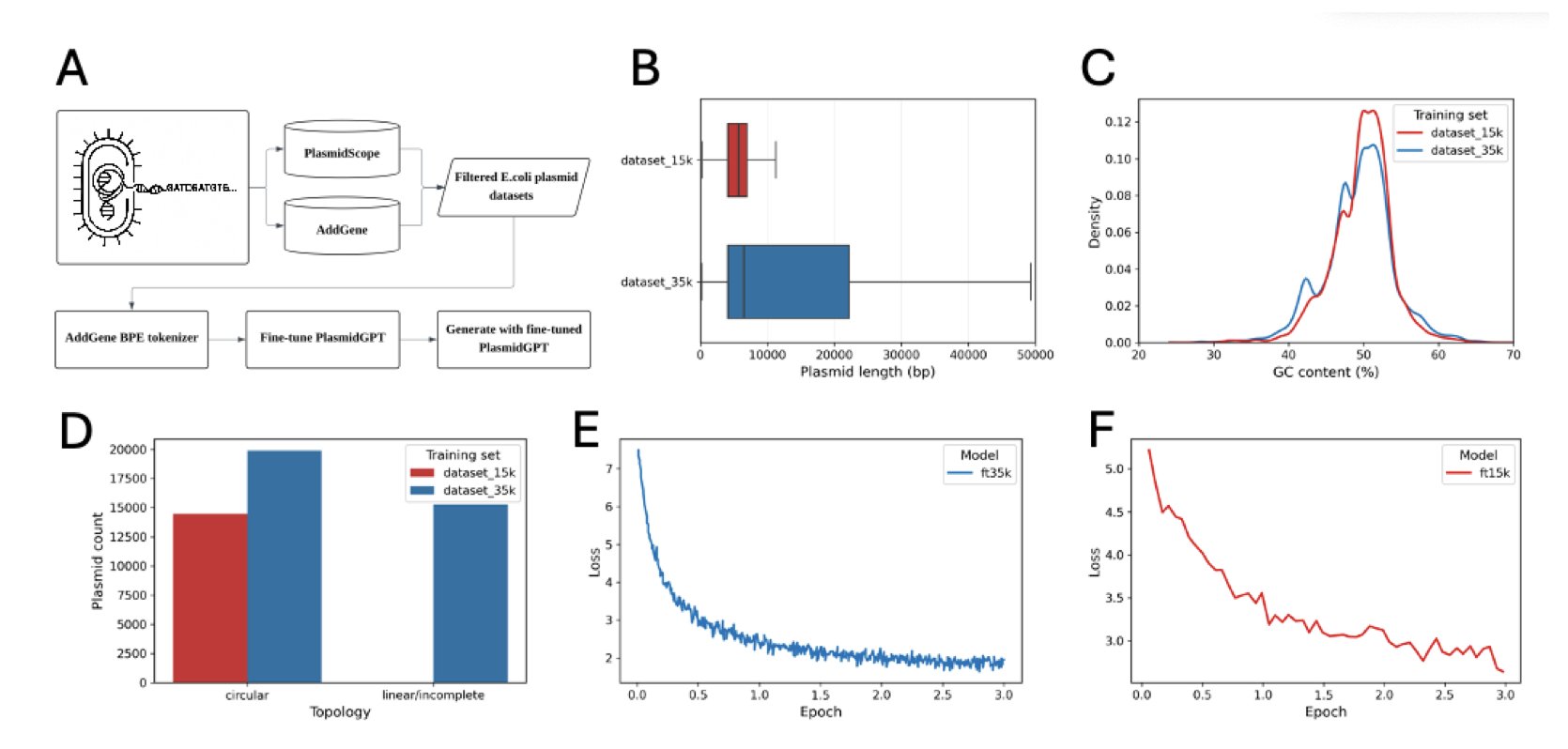

At the core of this research is a DNA large language model called PlasmidGPT. It’s like a GPT that has been trained to read only DNA sequences. Researchers trained it on a huge dataset of plasmid sequences, teaching it the “grammar” of plasmids, such as the structure and arrangement of essential elements like the origin of replication and selection markers (e.g., antibiotic resistance genes).

The researchers tried two methods to guide the AI’s design. The first was to give the model a simple promoter, ATG, as a seed and let it generate freely. This method didn’t work well; the quality of the generated sequences was inconsistent.

The second method was to give the model a complete Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) expression cassette as a prompt. This is like giving an AI a key paragraph and asking it to write the rest of the article around it. With the clear functional module of GFP as an anchor, the plasmid backbones generated by PlasmidGPT were structurally more sound.

The AI’s output needed to be filtered. The team generated 1,000 sequences and then used bioinformatics tools to screen them, checking for essential components and the absence of unusual restriction sites. After filtering, they had 16 candidate sequences.

They chose three of these for experimental validation. The researchers chemically synthesized the three DNA sequences and transformed them into E. coli. The results showed: 1. The bacteria successfully grew on a medium containing antibiotics, proving that the AI-designed resistance gene was functional. 2. The bacteria glowed green under UV light, proving that the AI-designed plasmid backbone could support the expression of the GFP gene.

This is the first time an AI-generated plasmid has been successfully validated in living cells. A string of code in a computer became a functional biological component inside a cell. In the future, it might be possible to give an AI a direct request, such as “design a plasmid to express insulin in yeast,” and then synthesize and test it. Although the current success rate for filtering is low (16 candidates from 1,000 sequences), the entire workflow from design to validation has now been established.

📜Title: Generative design and construction of functional plasmids with a DNA language model 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.06.692736v1

5. GRASP: Building Complex Pharmacology Models with Conversation

Drug development, especially for large molecules or drugs with complex mechanisms, relies on Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) models. These models predict a drug’s dynamics in the body and are an important tool for guiding decisions. But the barrier to QSP modeling is high. It usually requires a team of pharmacologists and modeling experts proficient in MATLAB. The process is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and dependent on individual experience.

The GRASP framework aims to change this. Its idea is to have an AI agent handle the programming and mathematical work, allowing domain experts to focus on the biology by giving instructions in natural language.

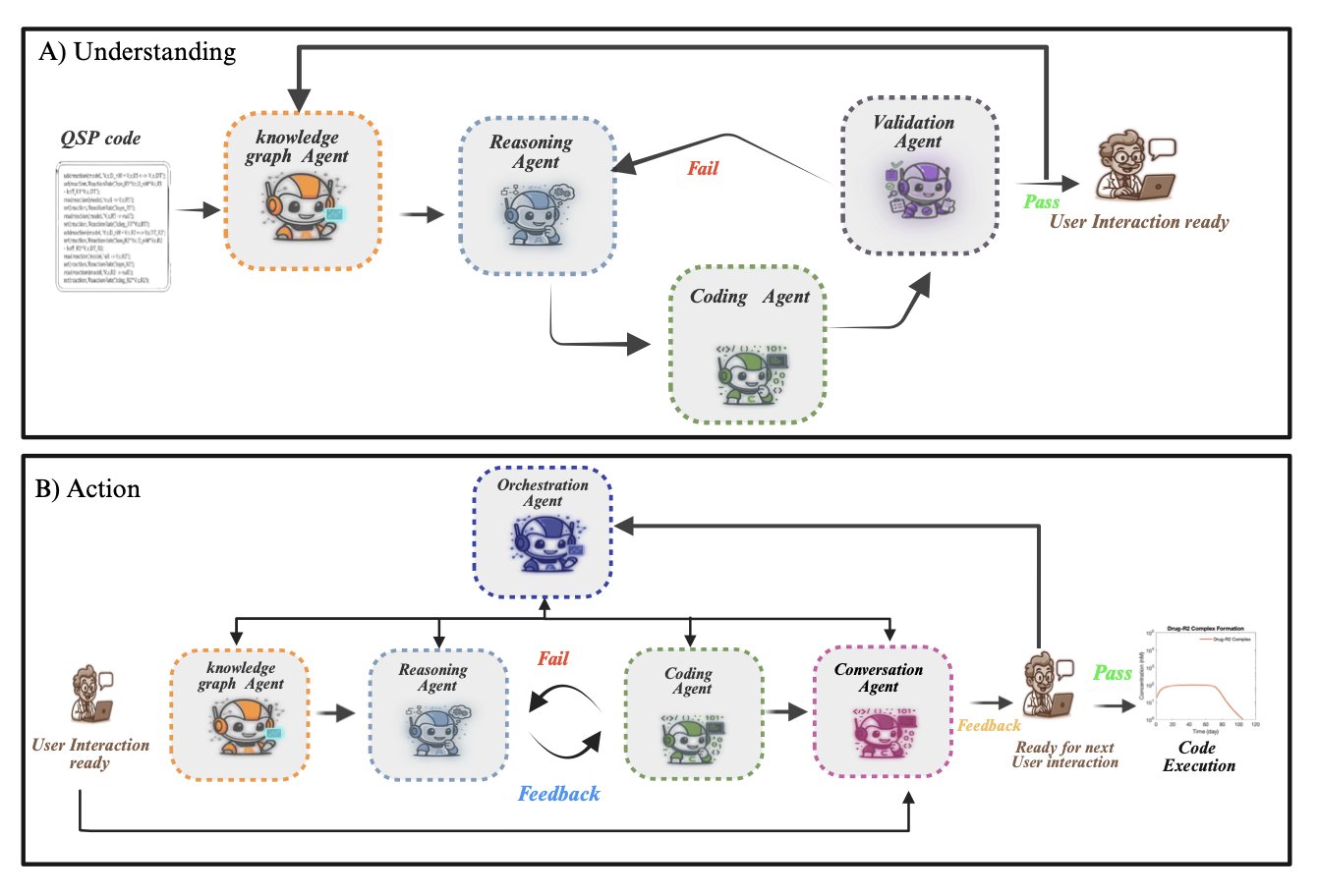

GRASP works in two steps.

The first step is “understanding.” Modeling work often involves modifying existing QSP models. This MATLAB code is usually complex and hard to read. GRASP first reads the code and “translates” it into a structured knowledge graph. This graph is like a mind map, showing all the components, parameters, and their relationships within the model. To ensure its understanding is accurate, GRASP also generates new code from the graph and runs it to verify that the results match the original code. This process is repeated until it can perfectly reproduce the original.

The second step is “acting.” Once the model is converted into a knowledge graph, a pharmacologist can give GRASP instructions in natural language, such as: “Add a target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD) mechanism to this model.”

Upon receiving the instruction, GRASP’s agent reasons on the knowledge graph. It knows that TMDD requires introducing new entities like a drug-target complex and defining new reactions like binding (kon), dissociation (koff), and internalization (kint) rates. It automatically updates the graph and modifies the MATLAB code to complete the model upgrade.

GRASP’s technical highlight: automatically maintaining model consistency.

The biggest challenge in adding new elements to a complex model is maintaining the consistency and accuracy of the entire system. It’s like adding a new gear to a precision watch; you have to make sure it works seamlessly with all the other gears.

GRASP uses a “breadth-first parameter alignment system” to solve this. Whenever a new entity or reaction is added, the system automatically checks all its dependencies on existing parts of the model to ensure that mass balance laws and physiological constraints are met. The system will even recommend a biologically plausible range for new parameter values based on existing ones. This frees experts from the tedious work of debugging equations and parameters.

A case study in the paper demonstrates GRASP’s real-world capabilities. Researchers had it handle a series of increasingly complex biological scenarios, from simple drug metabolism to adding TMDD and simulating multi-receptor interactions and cooperative binding. The entire process was done through natural language commands, and GRASP consistently maintained the model’s pharmacological validity and mathematical consistency.

GRASP is like a virtual assistant that understands both biology and programming. It makes building and iterating on QSP models as simple as discussing a plan with a colleague, freeing scientists from coding. If this technology matures, it will speed up the drug development process.

📜Title: GRASP: Graph Reasoning Agents for Systems Pharmacology with Human-in-the-Loop 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.05502v1

6. OMTRA: One Model for Drug Design, Docking, and Conformation Generation

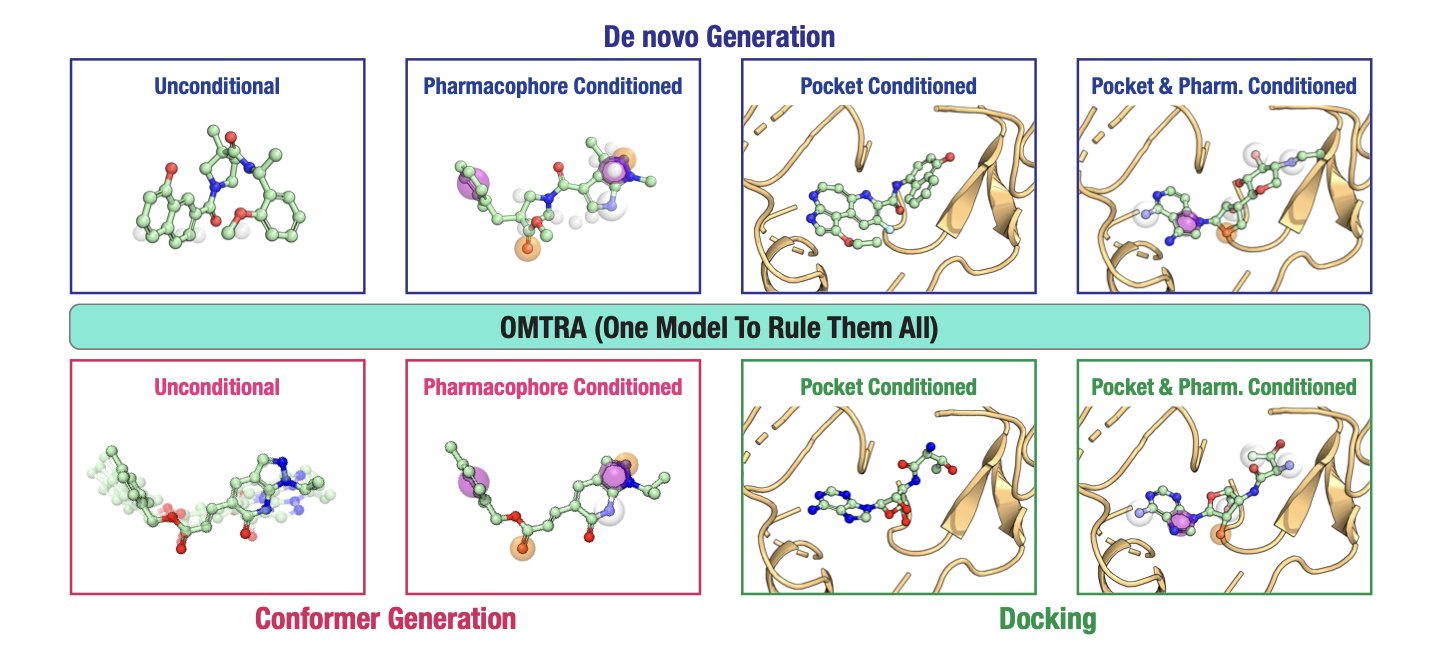

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) typically requires several specialized tools: one for molecular docking, another for generating new molecular scaffolds, and a third for generating a molecule’s 3D conformation. These tools work separately, making the workflow cumbersome. The OMTRA model attempts to complete all these tasks with a single “Swiss Army knife.”

OMTRA’s core technology is Flow Matching. The process of generating a molecule is like sculpting. Traditional methods like diffusion models are like condensing a molecule’s shape from a random “fog.” The process works, but the path is indirect. Flow Matching, on the other hand, sets a clear, smooth “track” for the model. The model starts from a simple, known distribution and transforms precisely along this track to arrive at the target molecule’s 3D structure.

This method can naturally handle two different types of data at the same time: continuously changing 3D atomic coordinates and discrete atom types (carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, etc.). OMTRA solves both of these problems within a single framework.

How well does this “Swiss Army knife” work in practice? The researchers tested OMTRA’s ability on specific tasks. For example, given a protein’s active pocket, they asked it to design a new molecule that could bind to it. The results showed that the molecules generated by OMTRA were chemically reasonable, and their predicted binding modes were reliable. It outperformed previous models on several evaluation metrics, demonstrating its practical utility.

A good model needs good data. Another highlight of this work is the creation of a large-scale dataset containing 500 million 3D molecular conformations. This “encyclopedia” allowed the model to see a sufficiently diverse molecular world, which is crucial for improving its ability to generalize. The dataset itself is a major contribution to the field.

An interesting finding was that as a multi-task model, OMTRA did not show significant synergy between tasks. Intuitively, one might think that learning molecular design, docking, and conformation generation at the same time would be mutually beneficial, creating a “1+1 > 2” effect. For example, learning to generate reasonable 3D conformations should help with protein docking. But the experimental results showed that this synergistic gain was limited or nonexistent. This reveals an important issue: how to achieve effective multi-task learning and knowledge transfer in the field of molecular generation is still an open challenge. Simply stacking tasks together does not guarantee a leap in performance.

The authors look toward the future of the model, planning to teach OMTRA to generate protein structures. If achieved, this would be a huge step forward. It would mean the model could handle docking with flexible proteins and even design drugs when the protein structure is unknown. It’s like being able to design a key not just for a fixed lock, but for a lock that can change its shape.

Overall, OMTRA is a well-designed and solid generative model that offers a viable way to unify multiple tasks in SBDD. At the same time, its experimental results reveal the limitations of multi-task learning at its current stage, and this honesty makes the work even more valuable.

📜Title: OMTRA: A Multi-Task Generative Model for Structure-Based Drug Design 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.05080 💻Code: https://github.com/gnina/OMTRA