Table of Contents

- MolAS picks the best docking algorithm, boosting accuracy, but it also reveals that the instability of the docking process itself is the bigger challenge.

- Top science AI models, regardless of architecture or training data, are converging. They are learning a similar internal “language” to describe the physical world, which may point to a more universal way of representing physicochemical laws.

- The PRIMRose model uses deep learning to efficiently predict the per-amino-acid energy impact of double InDel mutations, offering a high-resolution view for understanding protein function.

- The DeepSKA framework combines the speed of deep learning with the mathematical rigor of stochastic reaction networks, making simulations of complex biological systems faster, more accurate, and transparent.

- AlphaFold’s pLDDT score can roughly indicate a protein’s intrinsic flexibility, but it can’t capture conformational changes induced by molecules like drugs—a critical blind spot for drug discovery.

1. AI Boosts Docking Accuracy by 15%, But There’s a Catch

Molecular docking is a staple of drug discovery. Whether to use Glide, AutoDock Vina, or GOLD often comes down to a researcher’s habit. But no single algorithm works best for every situation.

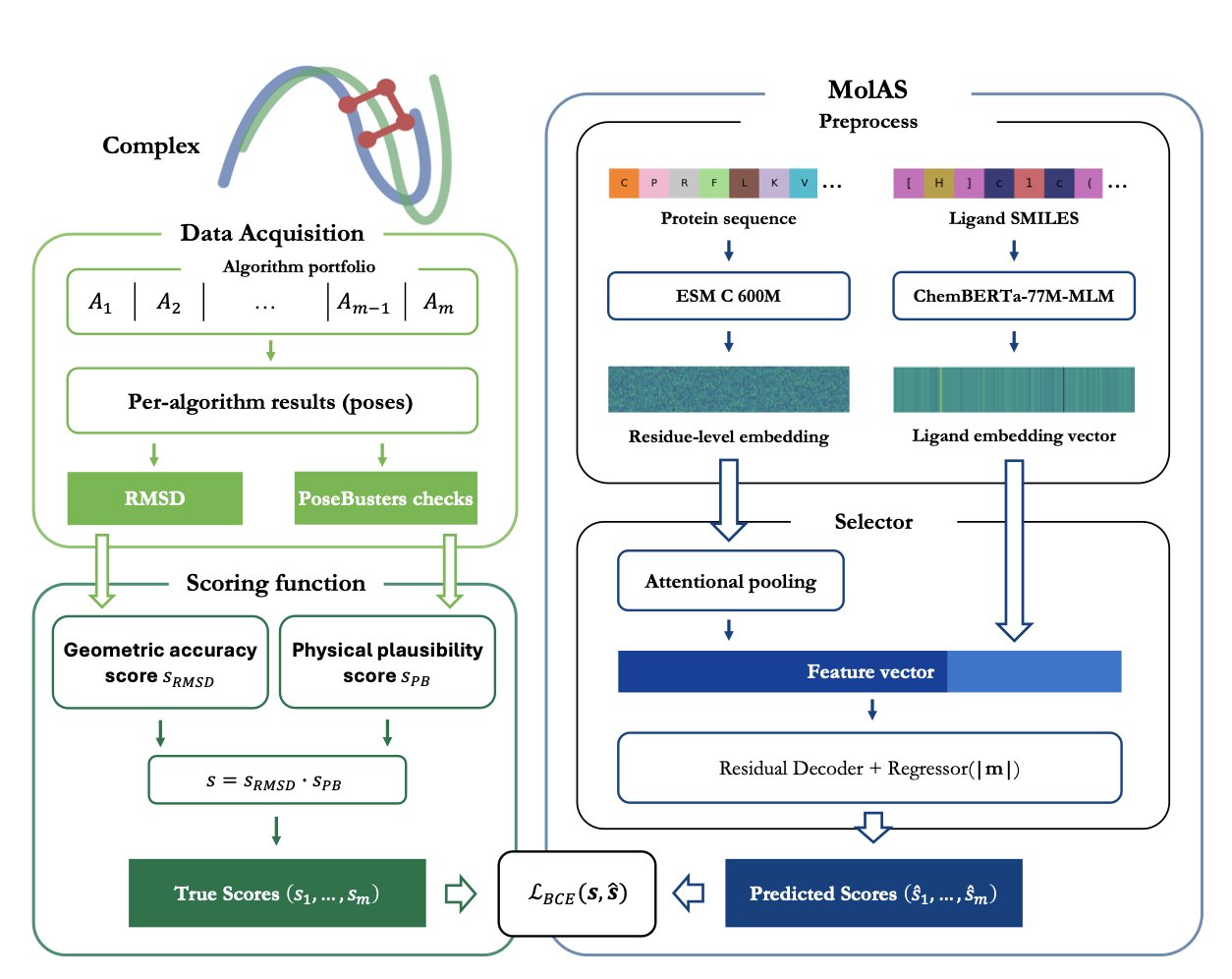

A recent study developed the MolAS system to solve this problem. MolAS acts like a project manager. It doesn’t perform the docking itself. Instead, it analyzes the molecular features of a protein and a ligand and then matches them with the most suitable docking algorithm—say, choosing Vina for one task and Glide for another.

The system is lightweight. It uses pre-trained molecular embeddings for proteins and ligands. You can think of these embeddings as digital fingerprints that contain structural and chemical information. MolAS feeds these fingerprints into a simple model to quickly predict which docking algorithm has the best chance of success.

Compared to relying on a single-best solver (SBS), MolAS can increase docking accuracy by up to 15 percentage points. In an ideal world where you always knew the best algorithm (a virtual best solver, or VBS), MolAS closes the gap between reality (SBS) and this ideal (VBS) by 17% to 66%.

But the study also uncovered a deeper problem: making the AI model more complex doesn’t systematically improve results. The real bottleneck is the fragility of the docking protocol itself.

Researchers often find that small tweaks, like changing the size of the docking box or updating the scoring function, can completely reshuffle the performance rankings of different algorithms. When the docking protocol is stable and consistent, MolAS works well because the algorithms’ performance is predictable. But if the protocol changes, it can cause wild swings in performance rankings (what the paper calls “protocol-induced hierarchy shifts”), making the predictions from MolAS useless.

It’s like trying to predict the winner of a race. If all the runners are in stable condition and the track is standard, predictions based on past performance will be accurate. But if the track keeps switching between dry, rainy, and muddy conditions, the original prediction model becomes meaningless. The docking protocol is the “track condition.”

So, this work offers a tool you can use right now: as long as your internal docking protocol is standardized, MolAS can improve efficiency. More importantly, it provides a new way to diagnose problems. It proves with data that the bottleneck in computational drug discovery may not be the AI models, but the robustness and reproducibility of the underlying simulation methods.

Future research should focus less on competing over model architecture and more on strengthening the fundamentals by building more stable and reliable docking workflows. Only when the “track” is standardized can predictive tools like MolAS deliver their full value.

📜Title: Molecular Embedding–Based Algorithm Selection in Protein–Ligand Docking 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.02328v1

2. The Collective Intelligence of Science Models: They’re All Learning the Same Physics

In computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), we are always comparing models: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Transformers, 3D models. We debate which architecture can best “understand” chemistry. A new study from MIT offers a fresh perspective by looking directly inside these models to see how they work.

The results were surprising.

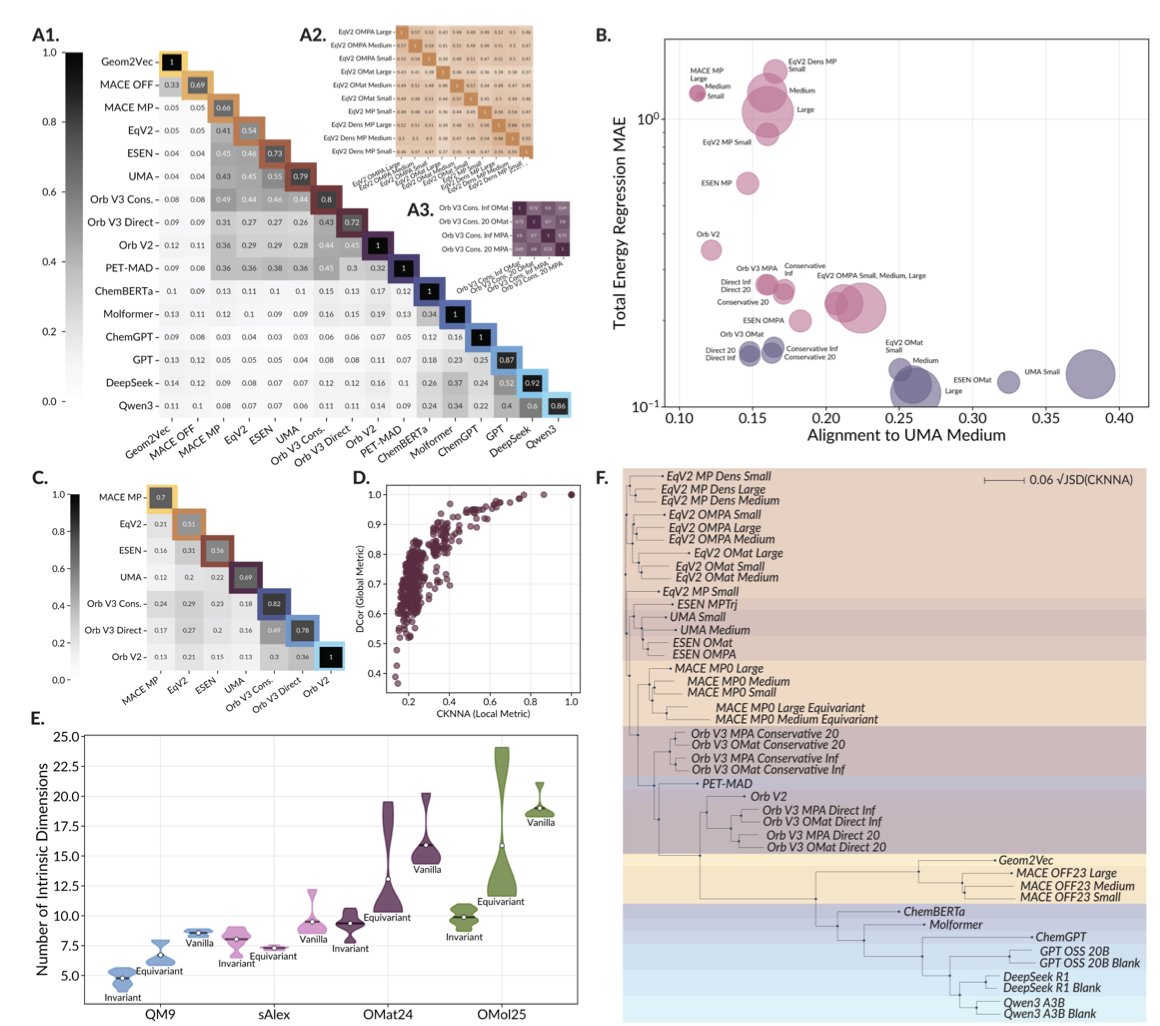

The researchers analyzed nearly 60 leading scientific foundation models. These models take all sorts of inputs: some read SMILES strings, others see molecules as graphs, and still others process 3D molecular structures. You would expect their internal ways of processing information (their “representations”) to be very different.

Using Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), the researchers found that the internal representations of these models are highly consistent. It’s like asking a group of engineers from different countries, speaking different languages, to independently design a bridge. In the end, their core mechanical blueprints would all follow the same physical principles. These AI models, regardless of their starting point, are all converging on a similar “understanding” of the physical world.

This convergence is directly linked to model performance. The internal representations of two high-performing models are almost interchangeable. In contrast, a poorly performing model’s “ideas” are out of sync with everyone else’s.

This offers a few insights for researchers.

First, the choice of model architecture may not be as critical as we think. What matters is that the model is powerful enough to learn this “universal chemical language.” When evaluating a new model, in addition to testing its accuracy, we could add another criterion: how well its internal representation aligns with top-performing models. If a new model can quickly learn this universal language, it means it has grasped the essence of the problem.

Second, the study also exposed a shared Achilles’ heel. When faced with a completely new molecule they’ve never seen before (out-of-domain data), all the models essentially surrender. They produce a vague, low-information representation, basically saying, “I don’t know what this is.”

This is a major problem in drug discovery, where the goal is to create new molecules that don’t exist in nature. It shows that the current bottleneck for AI is training data. The models haven’t seen enough diverse and unusual molecules, so their “imagination” is limited by the data they were trained on.

In the future, we might develop more general scientific foundation models that can understand small molecules, proteins, and novel materials all at once. A single model that could seamlessly understand a drug molecule and its target protein, and even predict their effect on material properties, would completely change how we design drugs and materials.

📜Title: Universally Converging Representations of Matter Across Scientific Foundation Models 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.03750v1

3. New AI Tool PRIMRose Decodes InDel Mutations, Amino Acid by Amino Acid

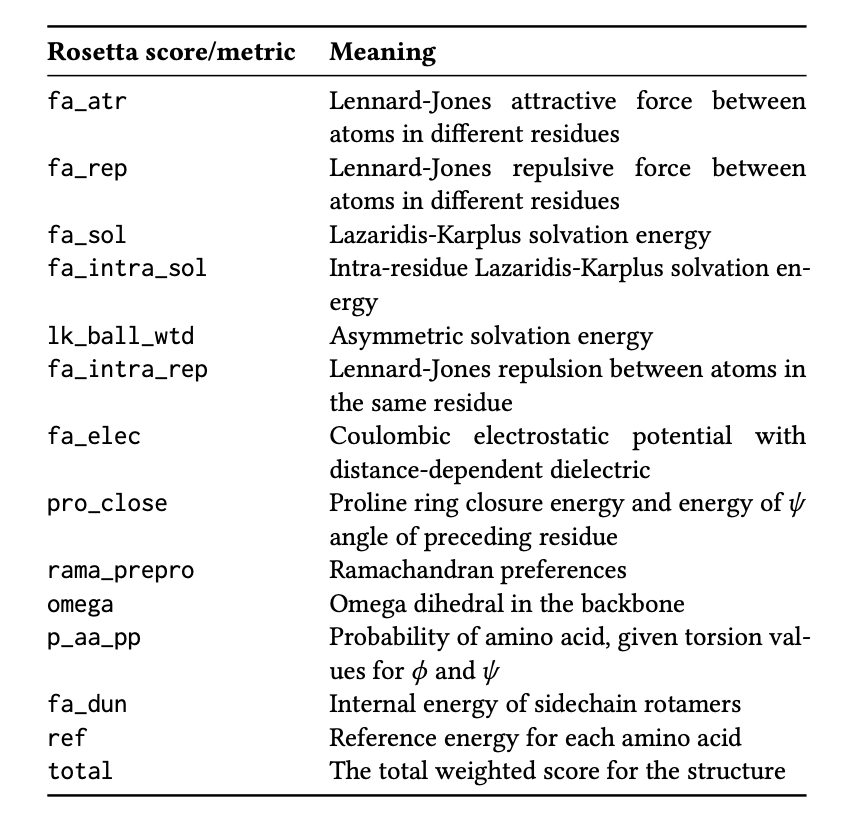

Protein engineering and drug discovery often involve inserting or deleting amino acids (InDels). It’s critical to assess how these small changes affect the entire protein. The traditional molecular simulation software, Rosetta, is reliable but slow. It also typically provides just a single value for the total energy change (ΔΔG), indicating whether the protein has become more or less stable overall.

This single score is like a diagnosis that says “the situation is not good” without specifying the problem. Researchers need more detail: How does the mutation affect different regions of the protein? Which amino acid residue is under the most stress? Which area has changed its structure?

The PRIMRose model was created to answer these questions. It provides an “energy report” detailed down to each amino acid residue, going far beyond a single summary score.

How It Works

PRIMRose uses a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The model works like an image recognition system, but instead of analyzing pictures, it analyzes protein sequences and mutation information. The research team trained the model on a dataset of nine proteins with hundreds of thousands of double InDel mutations. This taught the model to recognize the complex relationships between mutation patterns and energy changes in amino acid residues.

The training data came from Rosetta calculations. It’s like having a student (PRIMRose) learn from a seasoned professor (Rosetta). After graduation, the student can solve problems much faster than the professor.

A High-Resolution Perspective

The core value of PRIMRose is its per-residue analysis. It outputs an energy map, not a single number. This map shows how an InDel mutation can destabilize nearby residues or even affect residues that are far apart in the sequence but close in the 3D structure.

This map allows us to precisely identify a protein’s “structural weaknesses,” helping to avoid risks when designing mutations. When analyzing disease-causing mutations, it can also reveal how the energy balance of key functional domains is disrupted.

Speed and Interpretability

A complex mutation can take hours or longer for Rosetta to calculate. After an initial training of 1 to 6 hours, PRIMRose can predict a new mutation almost instantly. This boost in efficiency enables large-scale virtual screening, allowing researchers to evaluate the impact of thousands of mutation designs in minutes.

The model’s predictions are highly correlated with the physicochemical properties of proteins. For example, the model uses different prediction patterns for surface residues exposed to solvent versus residues buried deep in the core. This shows that PRIMRose has learned physical principles about protein secondary structure and solvent accessibility, which makes its predictions more interpretable and trustworthy.

PRIMRose is not meant to replace Rosetta. It’s an efficient screening tool. You can use it to quickly scan a large number of mutations, identify promising candidates, and then hand them over to Rosetta for detailed validation. It’s a much more efficient research strategy.

📜Title: Primrose: Insights into the Per-Residue Energy Metrics of Proteins with Double InDel Mutations Using Deep Learning 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.06496

4. AI Speeds Up Chemical Reaction Simulations with Reliable and Interpretable Results

In drug discovery and systems biology, we often deal with random processes, like fluctuations in protein expression inside a cell or the binding and unbinding of a drug molecule to its target. To describe these processes, we use Stochastic Reaction Networks (SRNs).

Traditional Monte Carlo simulation methods are accurate but computationally expensive. It’s like trying to estimate the area of a bullseye by throwing darts; to get a precise result, you need to throw a huge number of them. This is a major bottleneck in tasks that require many iterations, such as drug screening or model optimization.

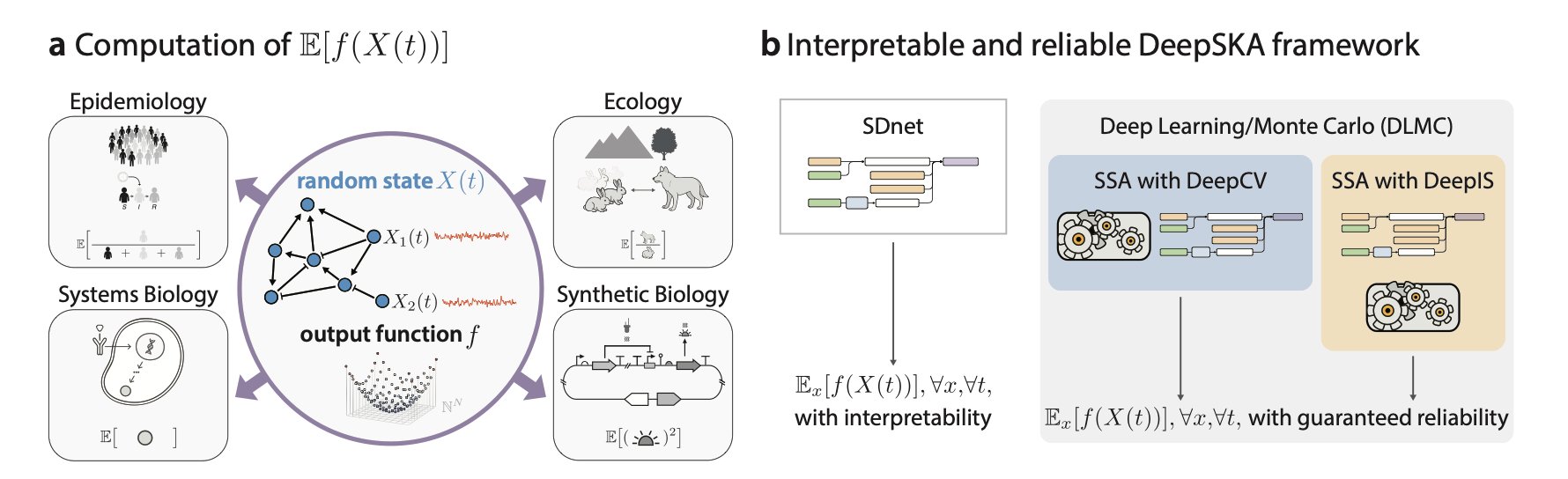

The DeepSKA framework takes a new approach by combining a deep learning model with traditional simulation, leveraging the strengths of both.

The first core component of the framework is a Spectral Decomposition-based network (SDnet). SDnet is designed to be interpretable; its structure directly reflects the mathematical properties of the system itself—its spectral decomposition. It’s like analyzing a symphony. You could listen to the whole thing over and over (brute-force simulation), or you could read the score and understand the main melody and harmonic structure (spectral decomposition). SDnet learns the system’s intrinsic “decay modes,” which are the basic ways the system returns to equilibrium from a different state. Because the network’s structure is directly linked to mathematical principles, we can understand the physical meaning of its predictions.

The second component is the Deep Learning/Monte Carlo (DLMC) estimator, which is the key to its efficiency. Traditional Monte Carlo simulations are slow because their results have high variance. The DLMC estimator uses the quick, approximate solution from SDnet as a “control variate.” This is like giving the Monte Carlo simulation an intelligent guide. As it “blindly” throws darts, the guide points to the general location of the bullseye. This reduces the random error in the simulation, speeding up convergence by several orders of magnitude while ensuring the result remains unbiased, just like a standard Monte Carlo method.

The researchers tested DeepSKA on nine different stochastic reaction networks, including complex models with non-linear and non-mass-action kinetics and up to ten species. The results showed that the framework’s prediction accuracy and generalization were excellent, performing robustly even when predicting time points beyond the training data range.

Beyond a system’s immediate dynamics, its long-term steady-state behavior is often more important. DeepSKA provides tools to calculate steady-state means and variances, such as the EM with DeepCV and DeepIPA algorithms, making it more valuable for practical applications.

In drug discovery, it can simulate the stochastic dynamics of drug-target binding more efficiently or predict the long-term response of signaling pathways. In synthetic biology, it can help design more stable and predictable gene circuits. By combining the computational efficiency of AI with the principles of physical chemistry, it allows us to explore complex systems faster and with a clearer understanding.

📜Title: Interpretable Neural Approximation of Stochastic Reaction Dynamics with Guaranteed Reliability 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.06294v1

5. AlphaFold’s pLDDT: A Reliable Indicator of Protein Flexibility?

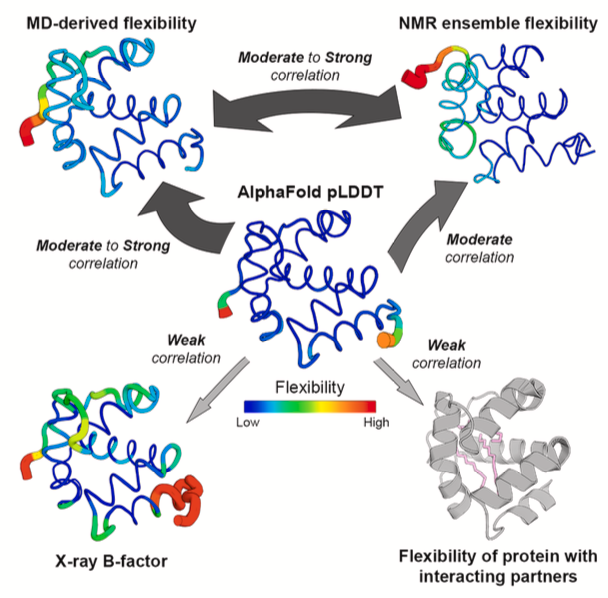

In protein structures predicted by AlphaFold, blue regions have high pLDDT scores, while yellow and red regions have low scores. Many people intuitively assume that a low pLDDT score indicates a flexible region of the protein. Is this common assumption accurate? It’s especially important in drug discovery, where the interaction between a drug molecule and a flexible protein pocket is crucial.

Vander Meersche’s team systematically tested this hypothesis. They directly compared AlphaFold’s pLDDT scores with two “gold standards” for measuring protein flexibility: Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR).

The results show that pLDDT does correlate with protein flexibility to some extent. Regions with low pLDDT scores generally show greater movement in MD simulations (as measured by RMSF values). So, it’s reasonable to use pLDDT as a rough guide for a protein’s intrinsic flexibility. It’s even a better indicator than the B-factor from crystal structures, as B-factors can be influenced by artifacts like crystal packing.

However, in drug discovery, the problem is more complex. Proteins in a cell don’t exist in isolation. They interact with drugs and other molecules, and these interactions can change a protein’s local conformation and flexibility. A flexible loop might get “locked” into a specific conformation after binding to a small-molecule drug. This “induced fit” is key to drug design.

The study found that AlphaFold has a blind spot here.

AlphaFold predicts a single state of a protein and has no knowledge of any ligands that might be present. So, even if a loop becomes stable upon binding a drug, AlphaFold will still give it a low pLDDT score because it lacks a stable template in its multiple sequence alignment, indicating low confidence in its prediction.

The researchers demonstrated this with MD simulations. When they simulated a protein alone, a certain region showed high flexibility. But when they added the protein’s binding partner (like another protein or a ligand) to the simulation, the flexibility of that same region immediately decreased. AlphaFold’s pLDDT score, however, remained unchanged, completely oblivious to the presence of the binding partner.

pLDDT reflects the model’s confidence in its predicted static structure. This is a different concept from a protein’s dynamic flexibility in a specific biological context.

Does the latest AlphaFold 3 solve this problem? The study tested it, and the answer is no. AlphaFold 3 showed no fundamental improvement over AlphaFold 2 in reflecting binding-induced changes in flexibility.

So, how should pLDDT be used? It can be a starting point to quickly identify potentially flexible regions in a protein’s “apo” state (unbound to any ligand). But if your research involves how drug binding affects protein conformation, or if you’re designing allosteric inhibitors that require conformational changes, pLDDT is not the right tool. In these cases, MD simulations, NMR, or other experimental methods are the reliable choices.

📜Title: Structure Flexibility or Uncertainty? A Critical Assessment of AlphaFold 2 pLDDT 🌐Paper: https://www.cell.com/structure/abstract/S0969-2126(25)00344-2