Table of Contents

- For kinase function prediction, probing the intermediate layer representations of a protein language model (ESM-2) yields more accurate and reliable results than using the final output layer.

- AIPheno uses generative AI for high-throughput extraction of digital phenotypes from images, discovering new genetic loci and generating images to visualize how genetic variations alter biological traits.

- DeepFEPS integrates five major algorithm classes, from Word2Vec to Transformers, and provides automated quality control reports to standardize and streamline feature vectorization for biological sequences.

- The FDD framework uses diffusion mapping to incorporate task supervision while preserving the geometry of pre-trained embeddings, offering a more effective alternative to traditional fine-tuning for antimicrobial peptide design.

- A study from UC San Diego shows that protein language models (pLMs) can accurately identify local structural similarities from sequence alone, without the need to construct 3D models.

- The CanBART model can generate genomic data for cancer patients just as a Large Language Model (LLM) writes sentences, solving the problem of data scarcity in rare cancer research.

1. A New Finding in Kinase Prediction: Mining the Middle Layers of Protein Language Models

Protein Language Models (PLMs), especially Meta AI’s ESM series, are standard tools in computational biology and AI drug discovery. Most applications use the output from the final layer as the protein’s feature representation. But a study by Ajit Kumar and Indra Prakash Jha suggests that for predicting kinase function, this approach might miss the most valuable information in the model.

Going Deeper into the Model’s Middle Layers

The researchers performed systematic Layer Probing on the ESM-2 650M model. They found that the final layer, while optimized for Masked Token Prediction, is not necessarily the best for representing protein function.

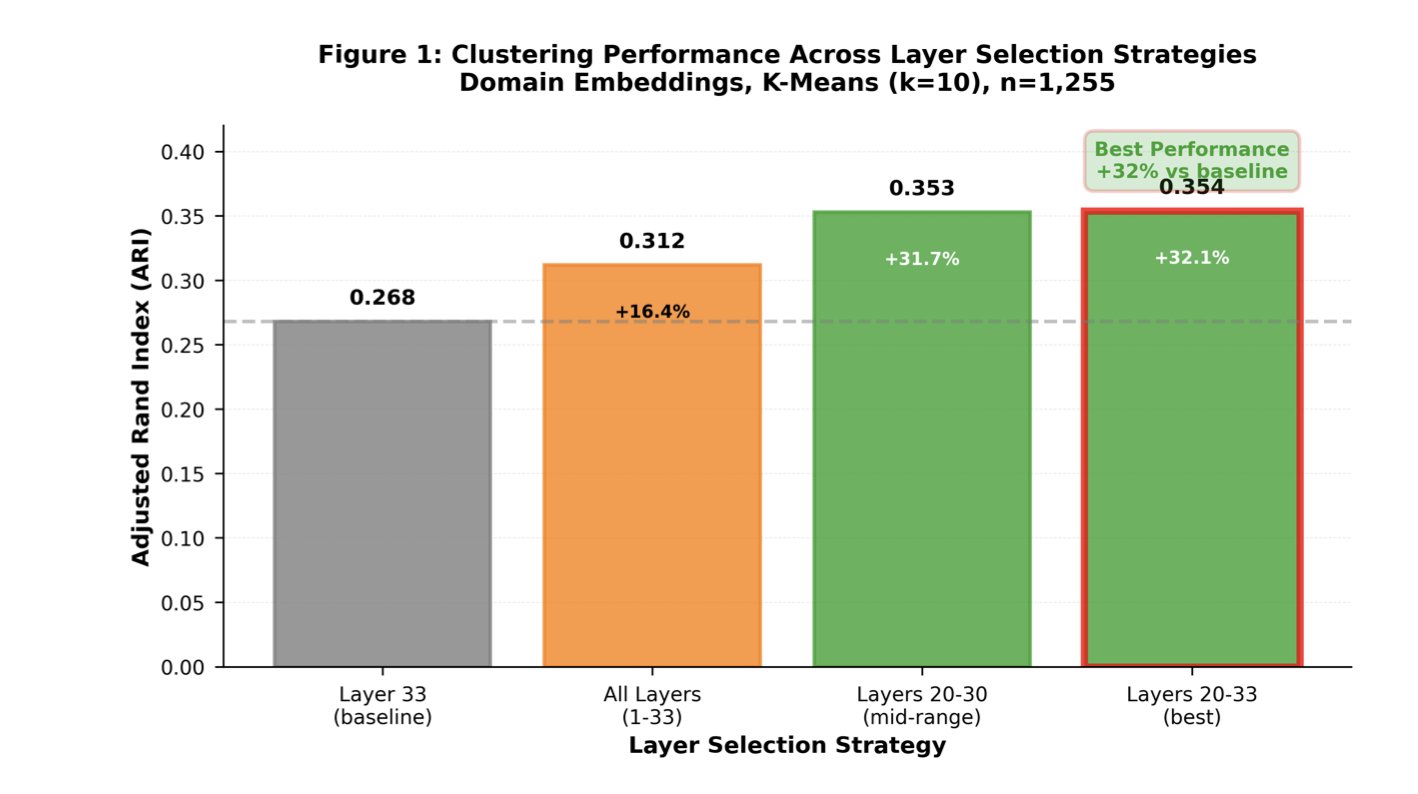

Think of it like a car assembly line. The final station shows a packaged box ready for shipping. To understand the engine’s inner workings—which corresponds to the protein’s functional properties—you need to look at an earlier stage of the process. The data confirmed this. When the researchers used features from layers 20 to 33 for unsupervised clustering, performance improved by 32% compared to using the final layer. This shows that the middle layers capture more of the subtle features related to biological function.

Improving Classification Accuracy and Prediction Confidence

This strategy also works for supervised classification tasks. By averaging the embedding vectors from layers 20 to 33, the model’s classification accuracy for kinase function reached 75.7%, better than relying only on the final layer’s output. This can help medicinal chemists reduce false positives when screening kinase targets computationally.

The study also focused on the reliability of predictions. When a model makes a prediction, it must also state its level of certainty. The researchers used Platt scaling to calibrate the classification probabilities, which reduced the expected calibration error by 28%. After calibration, a “90% confidence” output from the model is more trustworthy.

Practicality and Implications

This work establishes a complete workflow that includes Domain Extraction and confidence calibration. The ESM-2 650M model they chose strikes a balance between performance and computational cost, making it accessible to labs with limited computing resources.

The conclusion has direct value for drug developers: when using large models for downstream tasks, don’t assume the final layer is the best choice. Looking deeper inside the model and using representations from its middle layers can lead to more accurate predictions that better align with biology.

📜Paper Title: Layer Probing Improves Kinase Functional Prediction with Protein Language Models

🌐Paper Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.00376v1

💻Code Link: https://github.com/jhaaj08/Kinases-Clustering

2. AIPheno: Using AI to Read Images and Find New Links Between Genes and Traits

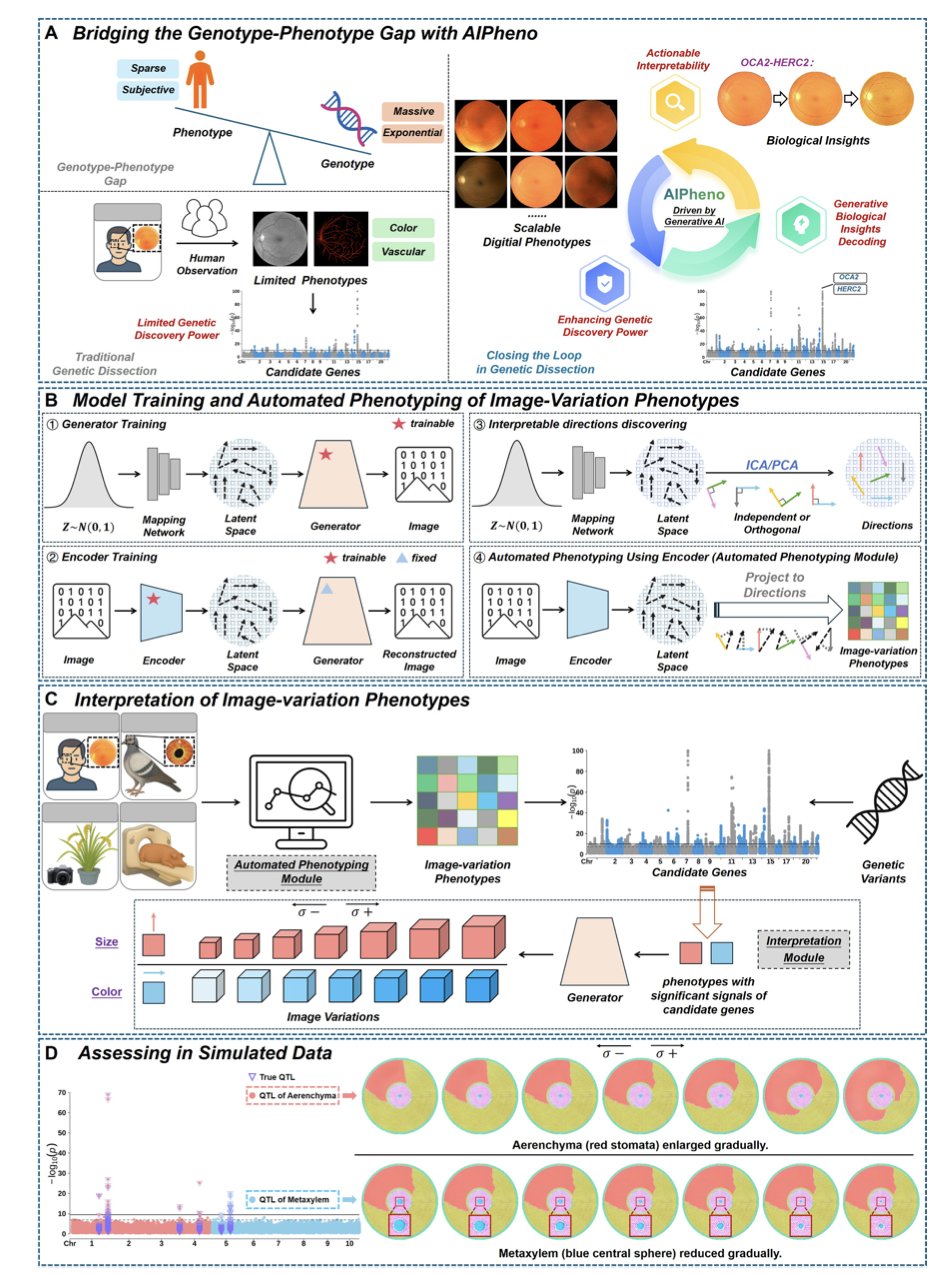

Genotyping is cheap and produces huge amounts of data. The real challenge is the phenotype. Even with massive amounts of individual genomes, describing features like leaf curl, subtle retinal structures, or body fat distribution still relies on manual measurements or simple image processing. This “genotype-phenotype gap” limits the depth of research.

AIPheno offers a new AI-based framework to fill this gap.

Translating Images into Data

AIPheno uses a unique encoder-generator architecture. It acts as a translator, converting complex medical or biological images into an optimized set of numbers (latent phenotypes) designed for comparison with genetic data.

This approach significantly boosts the power of genetic discovery. In experiments with humans, domestic pigeons, rice, and pigs, it outperformed traditional deep learning methods and identified previously overlooked loci, such as CCBE1 in humans and KITLG-TMTC3 in pigeons.

Opening the AI Black Box

AIPheno’s key advantage is its interpretability module. A traditional Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) only points out a correlation between a gene and a disease. AIPheno goes further to explain why. It can generate a synthetic image based on a specific genetic variant, visually showing how a mutation changes the physical form.

Take the OCA2-HERC2 locus, for example. By generating images, AIPheno showed that this locus affects retinal vascular features by regulating vascular visibility. This leap from correlation to biological mechanism provides key insights.

Closing the Loop

For animal and plant breeding, this helps in accurately selecting for desirable traits. For drug development, it can speed up the understanding of clinical phenotype changes caused by target mutations. AIPheno creates a closed loop from image to gene and back to biological meaning, providing data while also explaining the mechanism.

📜Title: Bridging the Genotype-Phenotype Gap with Generative Artificial Intelligence

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.13141

3. DeepFEPS: A Universal Toolbox for Biological Sequence Feature Extraction

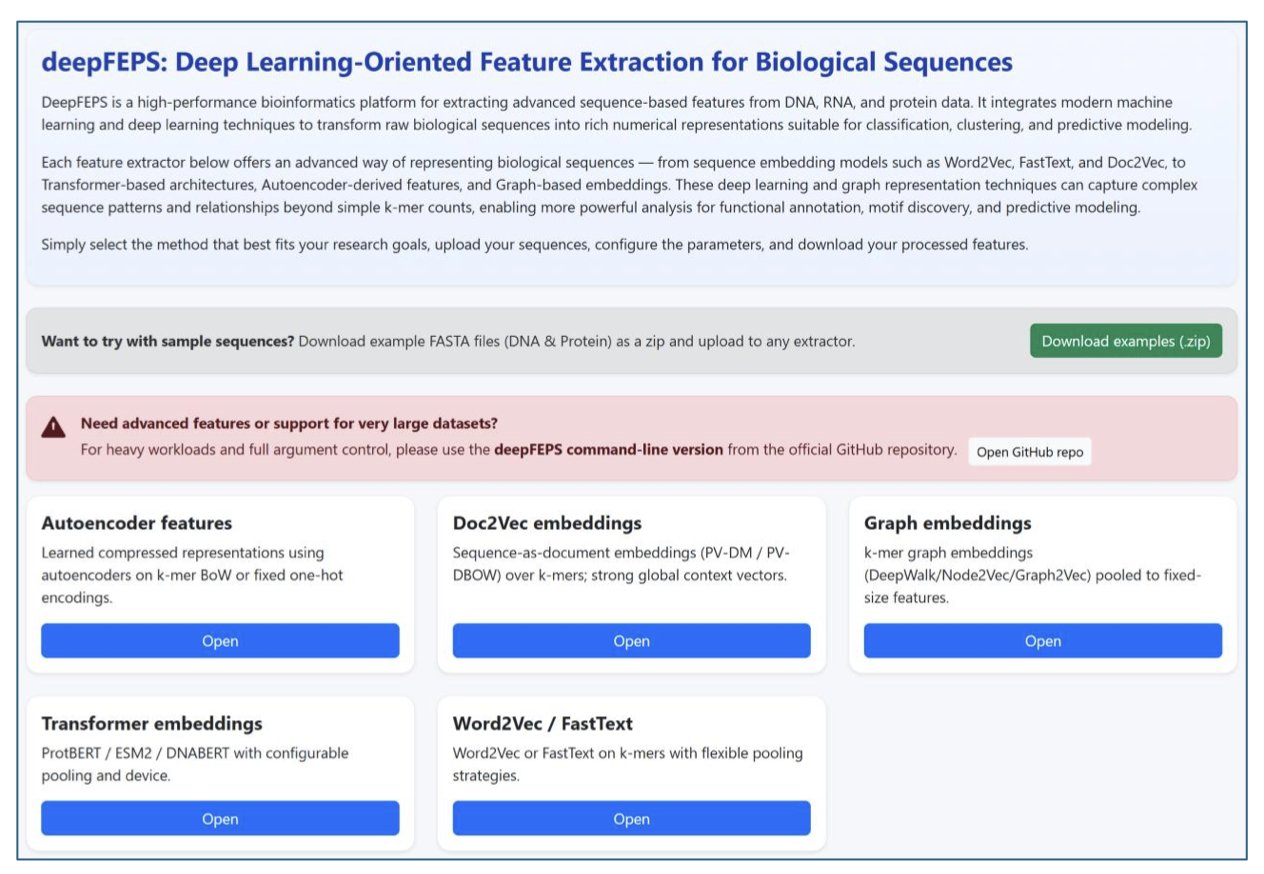

Processing raw DNA, RNA, or protein sequence data is a fundamental first step in bioinformatics and AI drug discovery. No matter how complex the downstream model is, the core task is to turn a sequence of letters into a high-quality numerical vector. DeepFEPS aims to solve the problem of fragmented feature extraction tools by offering a unified solution.

Compatible with Classic and Modern Algorithms

DeepFEPS integrates five major classes of methods. These include classic k-mer embeddings like Word2Vec and FastText, which are good for quickly processing local features, as well as popular Transformer-based encoders like DNABERT, ProtBERT, and ESM2.

With Transformer models integrated, users can call tools like ESM2 without setting up separate environments. This is critical for tasks that need to capture long-range sequence dependencies, such as protein structure prediction or regulatory element identification. The platform combines local feature capture with the global view provided by self-attention mechanisms.

A Quality Check for Features

DeepFEPS can automatically generate quality control reports. After feature extraction, the system outputs visualizations showing dimensionality, sparsity, variance distribution, and class balance.

Models often fail to converge because input feature vectors are too sparse or have zero variance. Generating these metric reports during preprocessing helps researchers spot data issues early, saving a lot of time on debugging later.

Flexible Interaction Modes

The tool offers two ways to interact: a web version for biologists doing exploratory analysis, and a command-line version for computational chemists and bioinformaticians to integrate into large-scale screening pipelines. As an open-source project, DeepFEPS is suitable for teaching and can be incorporated into industrial R&D pipelines.

DeepFEPS is designed with interfaces to integrate future models, making it highly extensible and suitable for researchers who want to test ideas quickly.

📜Title: DeepFEPS: Deep Learning-Oriented Feature Extraction for Biological Sequences

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.22821

4. The FDD Framework: Reshaping Antimicrobial Peptide Design with Geometry-Aware Diffusion, No Fine-Tuning Needed

Using Transformer models to process protein sequences is now common. The main challenge is adapting these large, pre-trained models for downstream tasks with limited data, like designing Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs). Traditional fine-tuning is expensive and can disrupt the model’s original general-purpose features. The authors’ proposed Freeze, Diffuse, Decode (FDD) framework offers a new solution.

Beyond Simple Feature Extraction

The core logic of FDD involves three steps:

- Freeze: Directly extract embeddings from a pre-trained Transformer. The model parameters are not changed at all. This treats the pre-trained model as a fixed feature extractor, saving resources and keeping the underlying features pure.

- Diffuse: This is the core of the framework. It introduces a supervised diffusion process to spread information across the embedding manifold. Data points in latent space are not isolated; they have a geometric structure. FDD propagates label information along this structure, preserving the original data topology and allowing the model to understand the task’s requirements.

- Decode: The geometrically adapted representations are mapped to the final output.

Performance in Practice

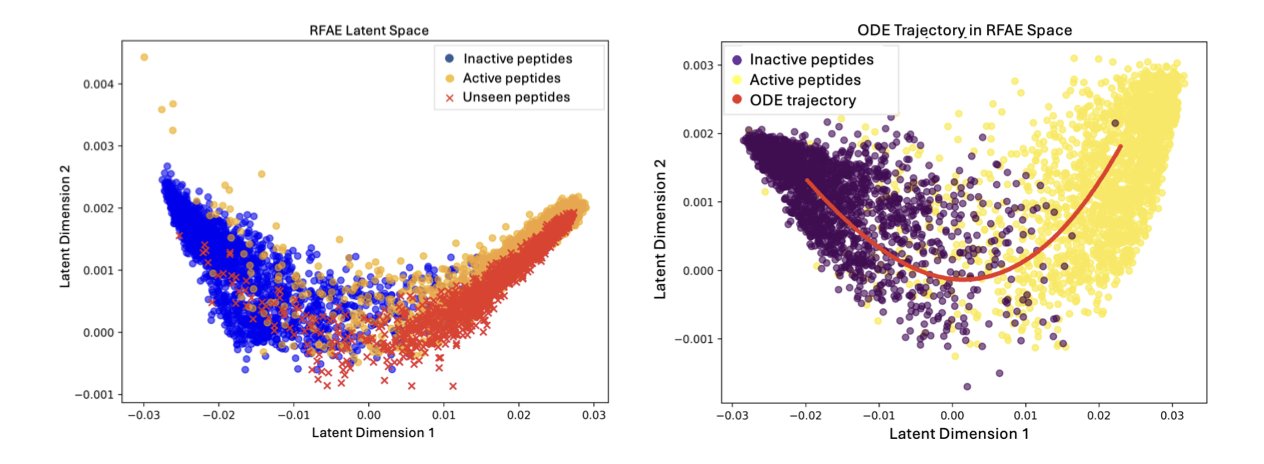

In an antimicrobial peptide design task, the authors compared FDD with traditional dimensionality reduction methods like t-SNE and autoencoders. The results showed that FDD achieved higher accuracy in binary classification tasks.

For retrieval ability, which is a key concern in drug discovery, FDD showed excellent robustness. It could identify peptides with antimicrobial activity from a completely new dataset, proving that it learned the biological essence of “antimicrobial” rather than just memorizing patterns.

Smooth Interpolation in Latent Space

FDD supports smooth interpolation in latent space. The authors demonstrated a gradual transition from a non-antimicrobial peptide to an antimicrobial one. Along the interpolation path, the peptide sequence changed continuously, and the predicted antimicrobial activity steadily increased.

This allows drug developers to perform directed optimization of molecular properties in latent space. This kind of biologically meaningful continuity helps address the shortcomings of many “black-box” models.

FDD allows the use of large models without retraining parameters. By fully leveraging the inherent geometric structure of the data, it’s possible to unlock the value of existing models with a lightweight approach.

📜Title: Freeze,Diffuse,Decode: Geometry-Aware Adaptation of Pretrained Transformer Embeddings for Antimicrobial Peptide Design

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.23120v1

5. Finding Local Protein Structures Using Only the Sequence

In structural biology, comparing two protein structures usually requires first getting their 3D models, whether by prediction with AlphaFold or by looking them up in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). This process is computationally expensive and time-consuming. A research team at UC San Diego has proposed a new idea: skip the 3D modeling and use protein language models directly.

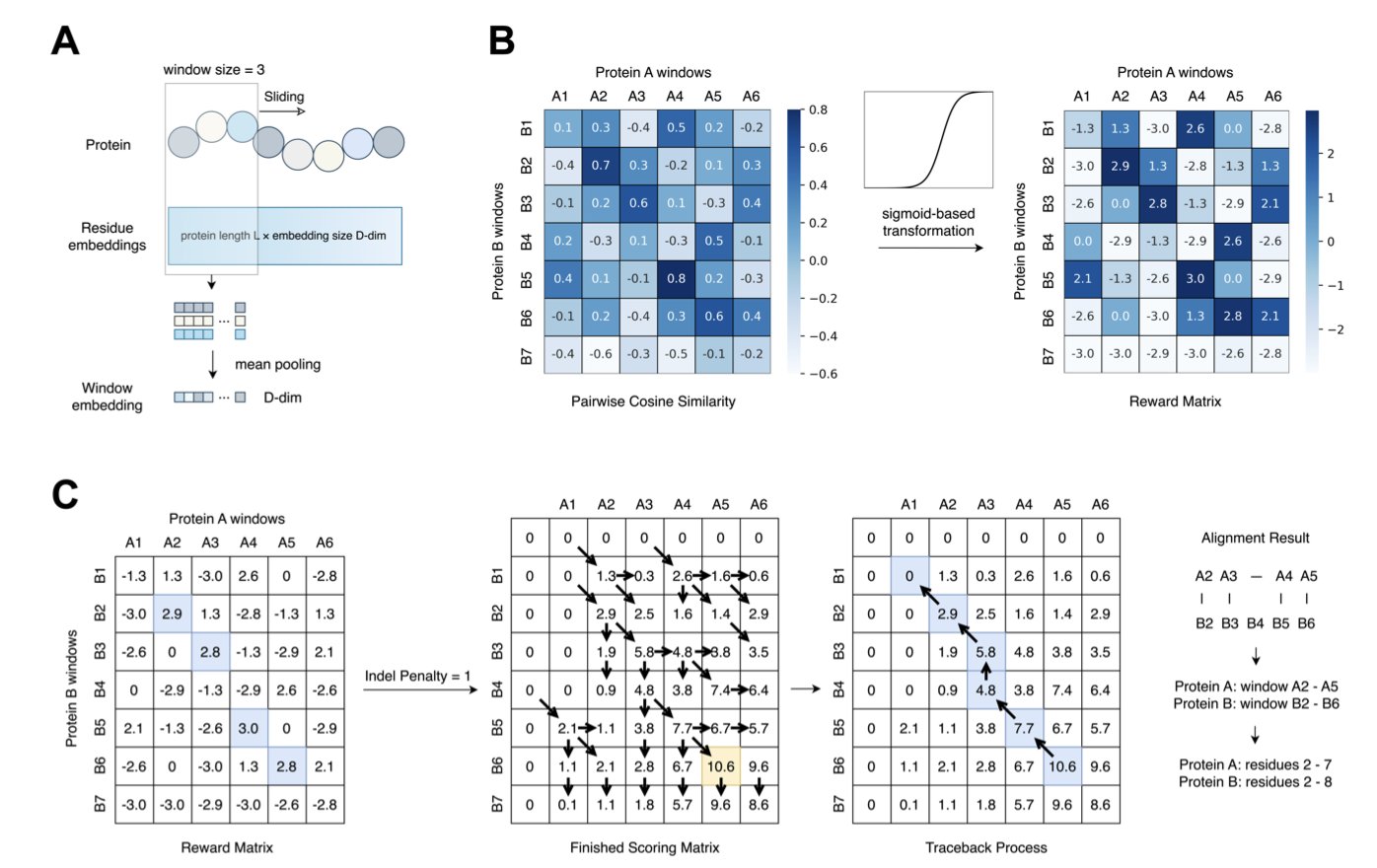

The Secret of the Sliding Window

The researchers developed a new framework that works like scanning a barcode. They use the protein sequence as input and apply a “sliding window” method to extract local embeddings, shifting the focus of analysis from the entire sequence to local fragments.

To pull a clear signal out of the noise, the researchers introduced a transformation step based on the Sigmoid function. This step amplifies faint similarity signals, making the true structurally aligned regions stand out, like using a directional microphone in a noisy room.

The Best Models

Among several models tested, ProtT5 and ProstT5 performed particularly well. ProstT5, a folding-aware model, was exposed to structural information during its training, so it is highly sensitive to structural features. In contrast, traditional methods based on residue alignment or predicted 3Di sequences (similar to Foldseek’s logic) can lose key subtle features by over-compressing information when handling local similarity tasks.

Real-World Test: The MALISAM Benchmark

To validate their method, the researchers used the MALISAM dataset. The proteins in this dataset share no common evolutionary ancestor and have no overall structural similarity, but they do have surprisingly similar structures in specific local regions. This poses a challenge for traditional methods that rely on sequence homology.

The results showed that the new method could accurately pinpoint these “hidden” local regions in various cases, achieving a structural similarity score (TM-score) greater than 0.5. This means that even if two proteins are evolutionarily distant, this tool can identify if they share a structurally similar functional domain, such as a binding pocket.

This technology is a practical tool for drug developers. When searching for the source of off-target effects or looking for structurally novel but functionally similar scaffolds, the ability to quickly scan for local structural similarity without 3D modeling can save screening time.

📜Title: Inferring Local Protein Structural Similarity from Sequence Alone

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.24.690129v1

6. CanBART: Using a Language Model to Generate Synthetic Cancer Patient Data

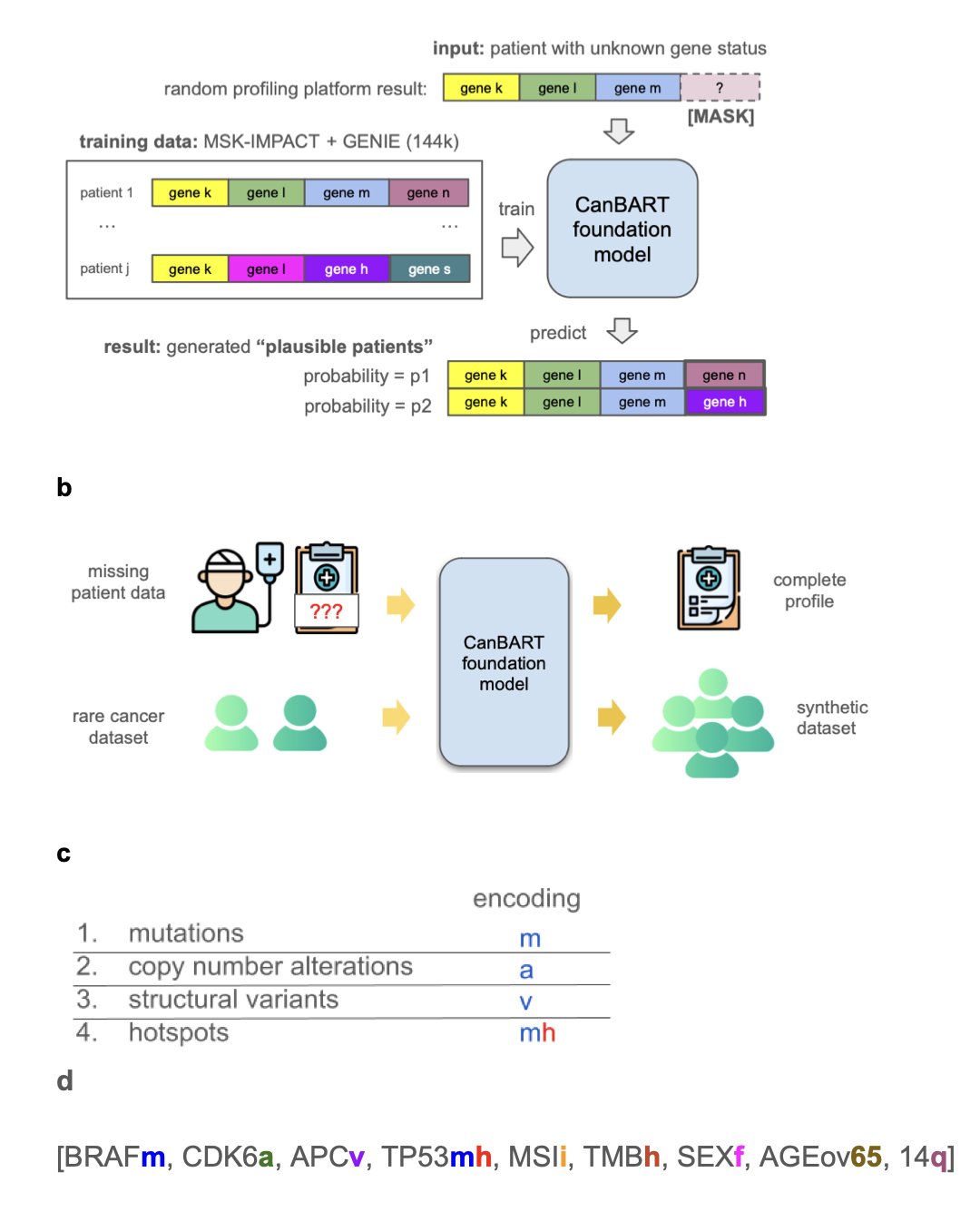

The central bottleneck in cancer drug development is data. For rare cancers, it is especially hard to find enough patient samples for research, which slows down the understanding of disease mechanisms and the development of new drugs. A new study offers a solution: using AI to create credible synthetic patient data.

The core of this solution is the CanBART model, which was trained to learn the “genetic language” of cancer. Researchers trained the model on genetic mutation data from over 144,000 cancer patients. This data records each patient’s genetic changes in a unique “molecular language.” CanBART’s job was to learn the rules of this language.

CanBART works similarly to a Large Language Model (LLM). It treats each gene mutation as a “word” (token), and a complete patient genetic profile becomes a “sentence” made of these special “words.” By learning from a massive number of these “sentences,” CanBART mastered the patterns of gene mutation combinations in different cancer types, such as which mutations tend to appear together.

Once it learned these patterns, CanBART gained two capabilities.

The first is completing incomplete genetic profiles. Clinical tests often provide only partial genetic information, like an incomplete sentence. CanBART can infer the missing gene mutations based on the rules it has learned. In a test with real-world data, it successfully predicted over a third of the missing gene mutations. This ability could help optimize clinical trial design and precision medicine.

The second is creating biologically plausible synthetic patient data. After learning how to “write sentences,” the model can generate new, complete synthetic patient genetic profiles. For rare cancers with very few samples, researchers can use CanBART to generate a virtual patient cohort. Although the data is synthetic, its gene mutation patterns are highly similar to those in real patients. Tests showed that using this synthetic data improved the classification accuracy for rare cancers by 66%, demonstrating that virtual data can effectively make up for a lack of real data and advance research into complex diseases.

This work opens up a new way of thinking: when real-world data is hard to get, using generative AI to create high-quality synthetic data can be a powerful engine for driving research forward.

📜Title: CanBART: A Generative Foundation Model of Cancer Molecular Alterations for Synthetic Patient Generation and Genomic Profile Completion

🌐Paper: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.04.25339512v1