Table of Contents

- Researchers restored the original data and evaluation protocol from the 2014 Tox21 challenge and found that the many new algorithms of the past decade have not significantly outperformed the original winner.

- An updated DAVIS dataset, which includes mutation and modification data, reveals that docking-free AI models tend to overfit to wild-type proteins, showing that structural prior knowledge is crucial for predicting real biological complexity.

- The protein structures generated by diffusion models have an internal mathematical mechanism that builds a thermodynamic energy landscape highly consistent with classical physics engines like Rosetta.

- General-purpose DNA foundation models underperform specialized models on specific tasks like gene expression prediction, but multi-species data training and a mean-pooling strategy can significantly boost performance.

- OpenBioLLM shows that a multi-agent system built from small, specialized open-source models can achieve better efficiency and accuracy on genomic question-answering tasks than a single large model.

1. Restoring the Real Tox21: A Decade of Stagnation in AI Toxicity Prediction

A medicinal chemist who hears that “AI solved toxicity prediction a decade ago” would probably just laugh. But in computational chemistry papers, a new state-of-the-art model seems to appear every few months. This paper reveals the truth behind that contradiction: we might have been running in place all along.

The Mess of Benchmarking

The 2014 Tox21 Data Challenge aimed to use computational methods to predict how compounds interfere with nuclear receptors and stress response pathways. It was like the ImageNet of AI for drug discovery. But ten years later, the Tox21 dataset everyone uses is a distorted version of the original.

As various open-source libraries were updated, the dataset was repeatedly “cleaned,” “split,” and “optimized.” The high scores today’s models achieve come from the test getting easier or the rules being changed. This phenomenon is known as “benchmark drift.”

To find out what was really going on, the researchers did some hard work: they went on an archaeological dig. They hunted down and strictly restored the original challenge’s dataset splits and evaluation protocols.

The Awkward Truth

The researchers took models that claimed to use advanced architectures, like self-normalizing neural networks, and put them back in the original 2014 testing environment to compete against that year’s winner, DeepTox.

The results showed that the fancy new algorithms didn’t have a clear advantage. DeepTox, a method built ten years ago on basic descriptors and traditional machine learning, was still in the top tier.

The decade-long “arms race” of algorithms in toxicity prediction hasn’t translated into an ability to solve real chemistry problems. Simply changing the number of network layers can’t solve the problems of noisy data and biological complexity.

No More “It Worked on My Machine”

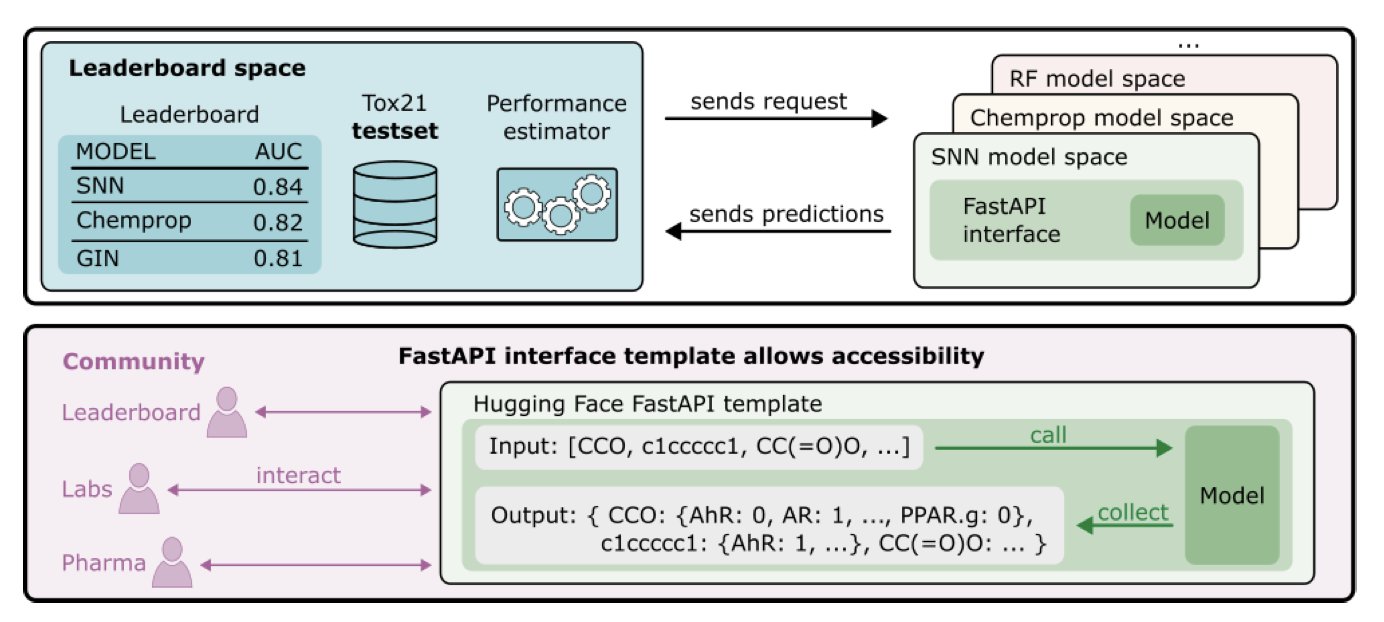

To put an end to the self-reported results, the team built a truly reproducible leaderboard on Hugging Face.

The core logic of this system is tough: upload containers, not results.

Participants must package their models using a FastAPI template and submit them. The system then automatically runs inference in a unified environment. This approach completely shuts down excuses like “special local preprocessing” or “different ways of calculating evaluation metrics,” returning to the transparency, reproducibility, and standardization that science requires.

This paper sends a signal to everyone in AI drug discovery: stop blindly trusting the high-score charts in papers. We need more work that goes back to the basics and verifies whether these expensive AI models actually understand more chemistry than a random forest from ten years ago.

📜Title: Measuring AI Progress in Drug Discovery: A Reproducible Leaderboard for the Tox21 Challenge 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.14744

2. Upgrading the DAVIS Dataset: The Challenge for AI in Predicting Protein Mutation Effects

Moving Past Idealized Data: Real-World Proteins Are Complex

Drug discovery researchers generally know that the benchmark datasets we often use are too idealized. Take the classic DAVIS dataset, which has long been the standard for evaluating kinase inhibitor affinity. Its flaw is that it only contains wild-type proteins. In the clinic, doctors often face kinases with various drug-resistance mutations or proteins that have undergone post-translational modifications, like phosphorylation. If an AI model can only predict binding for a standard protein, it’s still a long way from precision medicine.

A Major Data Upgrade

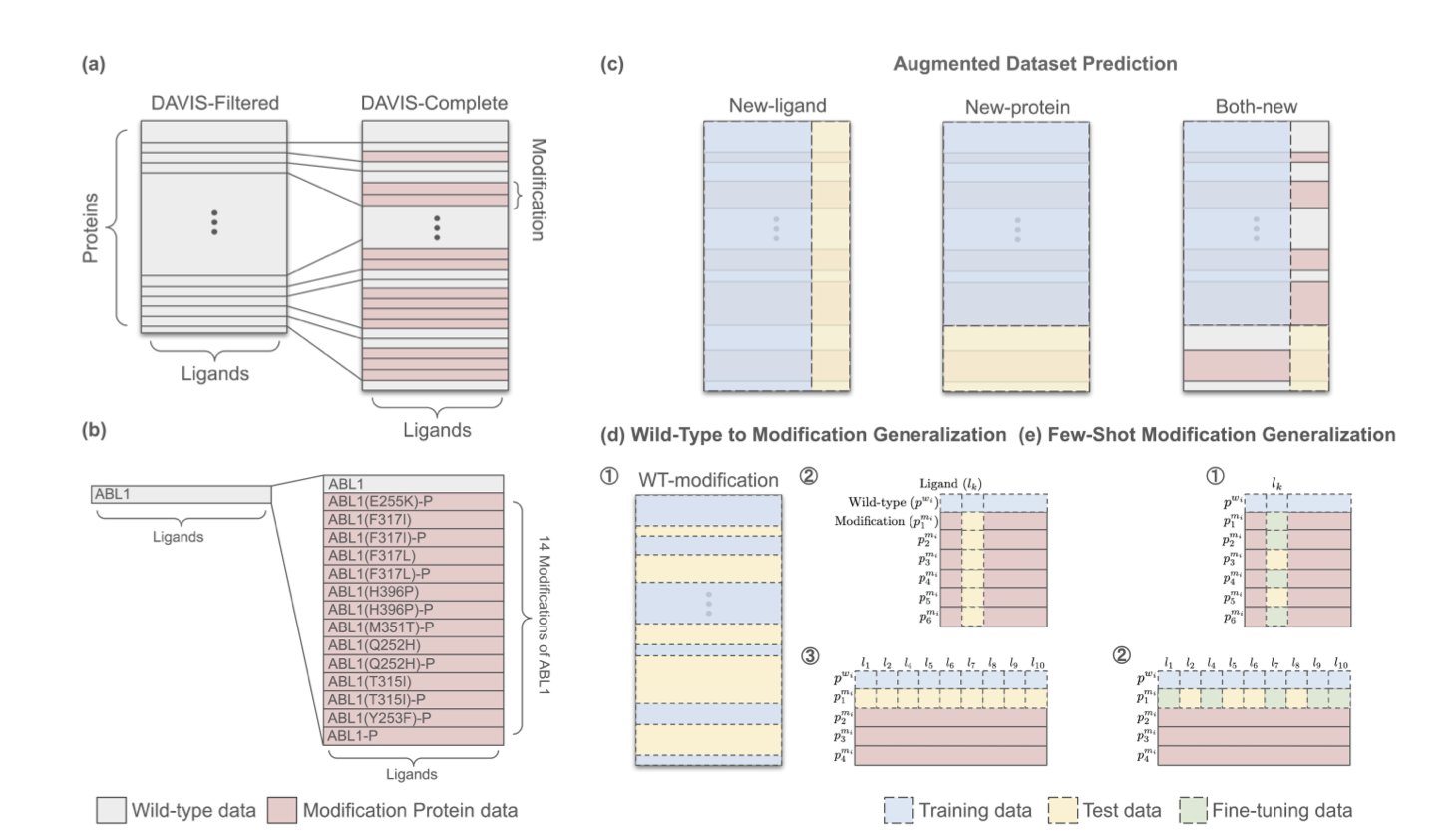

The researchers have released an upgraded version of the DAVIS dataset. They mined literature and databases for details that were previously overlooked: amino acid substitutions, insertions, and deletions, as well as key phosphorylation modifications. They ended up with 4,032 new kinase-ligand data pairs. This wasn’t just about adding more data; it was about adding a new dimension of complexity, forcing models to understand how tiny structural changes can dramatically affect binding activity.

A Real Test of AI Model Capabilities

Using this more challenging test, the researchers set up three new scenarios: 1. Data-Augmented Prediction: Testing a model’s ability to learn from the new data. 2. Generalizing from Wild-Type to Mutants: Simulating the most difficult scenario in real-world drug design—predicting a protein’s behavior after mutation based only on data from the normal protein. 3. Few-Shot Mutant Generalization: Giving the model a small number of mutant examples to see if it can learn from them.

The results showed that current AI models that rely only on sequences face a serious challenge.

Models that don’t rely on docking performed reasonably well on wild-type proteins but showed their flaws in the new tests. They were mostly memorizing protein names and sequence features instead of truly understanding the physical and chemical properties of the binding pocket. When a small mutation occurred in the sequence, these models often failed to react correctly, with their predictions stuck at the wild-type level—a classic sign of overfitting.

Structure is Key

In contrast, models like Boltz-2, which explicitly use structural information (docking-based), showed a clear advantage in the zero-shot tests. That’s because a mutation changes the spatial shape or charge distribution of the pocket, and algorithms based on physical structure can capture these changes in steric hindrance or interactions.

The lesson for the industry is that to achieve precision medicine, especially for designing drugs against resistance mutations, we can’t just rely on a Large Language Model (LLM) to process sequences. We have to deeply integrate prior knowledge from structural biology—whether from real crystal structures or high-quality predicted structures—into our models. In the complex world of biology, purely data-driven methods that ignore physical principles won’t get very far.

📜Title: Towards Precision Protein-Ligand Affinity Prediction Benchmark: A Complete and Modification-Aware DAVIS Dataset 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.00708v1

3. Diffusion Models Learn Thermodynamics: Extracting Physical Energy from AI

Diffusion models are surprisingly good at predicting protein structures. But developers have a nagging worry: is the model just “memorizing” geometric shapes from the PDB database, or does it actually understand the physical laws of molecular forces? If it’s only imitating, the risks in drug design for new targets are huge.

This new study tries to open the black box and finds that diffusion models learn thermodynamics during training.

The Denoising Process is a Search for a Low-Energy State

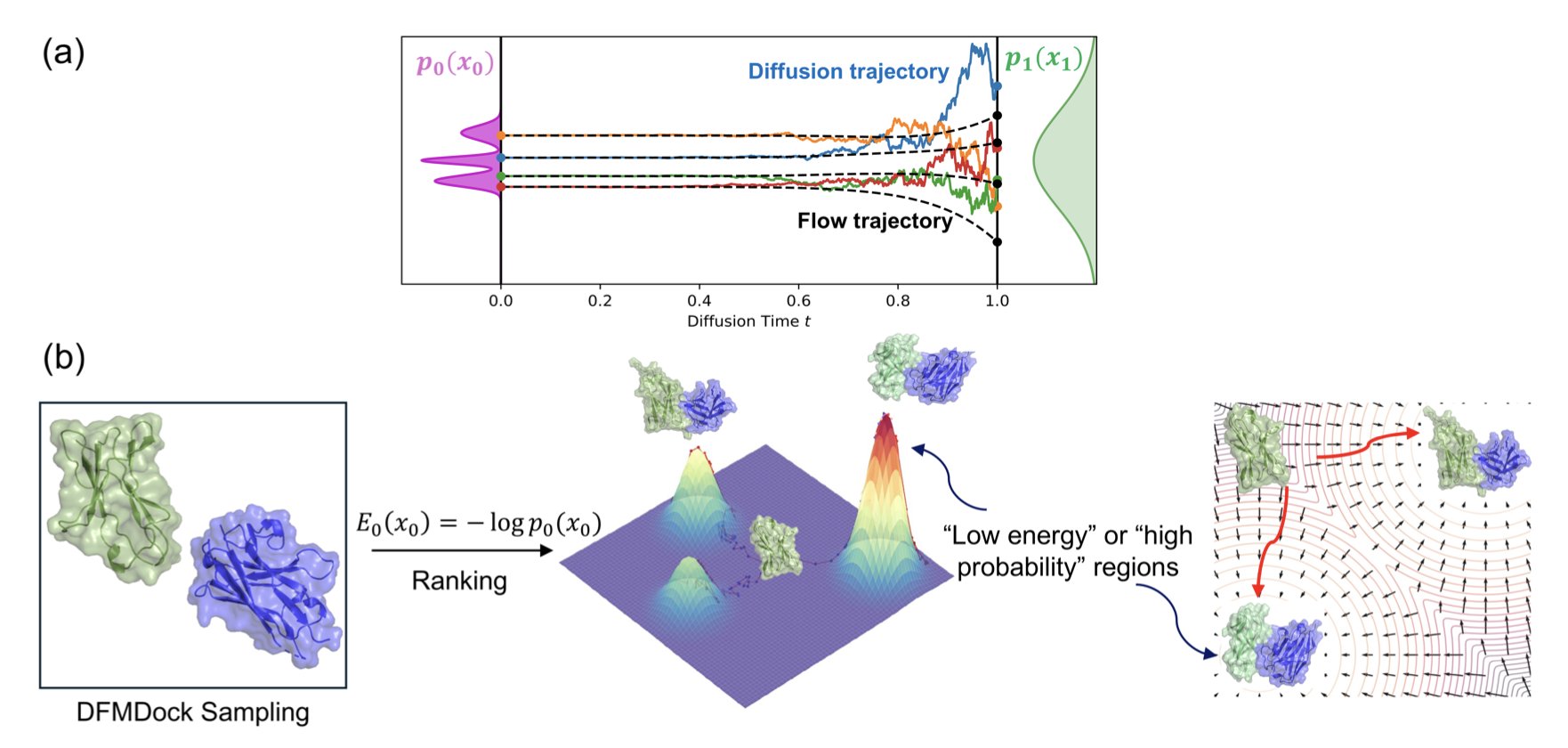

The researchers propose an underlying theoretical framework. The core of a diffusion model is adding and removing noise. The paper points out that the mathematical process of denoising maps to the Boltzmann distribution in thermodynamics. Structures the model considers “high-probability” correspond to “low-energy” states in physics. The model’s negative log-likelihood is essentially a pseudo-potential energy function.

Mapping the “Energy Funnel”

The researchers used a protein-protein docking model (DFMDock) to test this idea. In computational chemistry, a key metric for classic physics software like Rosetta is the “energy funnel”—the correct binding pose sits at the bottom of an energy valley, surrounded by higher-energy conformations that form the steep walls of the funnel.

The “energy” extracted from a pure AI model like DFMDock can also plot a clear energy funnel. The AI isn’t just guessing; its high-scoring conformations correspond to physically stable states. In some tests, this AI-derived energy score was even better than Rosetta’s scoring function at identifying the native conformation.

Blurring the Lines Between Statistics and Physics

This finding blurs the line between AI and physics. If you feed an AI enough real physical structure data, it can “reverse-engineer” the underlying physical laws (the energy landscape) through statistics.

This creates a new opportunity for drug discovery. If we can directly extract physics-level energy from large models like AlphaFold3, we might not need to run separate, expensive molecular dynamics simulations to validate the results. The AI itself becomes a calculator with a built-in physics engine.

For now, this finding has mainly been validated on rigid docking. Whether it can handle flexible side chains or more complex conformational changes remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: the machine has learned some real physics.

📜Title: Can We Extract Physics-like Energies from Generative Protein Diffusion Models? 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.28.690021v1

4. In-Depth Review: How Do 5 DNA Foundation Models Perform in Practice?

It makes sense to treat DNA as a language and apply Transformer architectures from natural language processing (NLP). A flood of DNA foundation models has hit the market: DNABERT-2, Nucleotide Transformer V2, HyenaDNA, Caduceus-Ph, and GROVER. But are they actually any good? Which one is the “GPT-4” of this field?

A recent study in Nature Communications conducted a deep, head-to-head comparison of these five models. Unlike the marketing materials, this research offers more valuable conclusions.

How to Read the Data? The Class Average is More Reliable Than the Class President

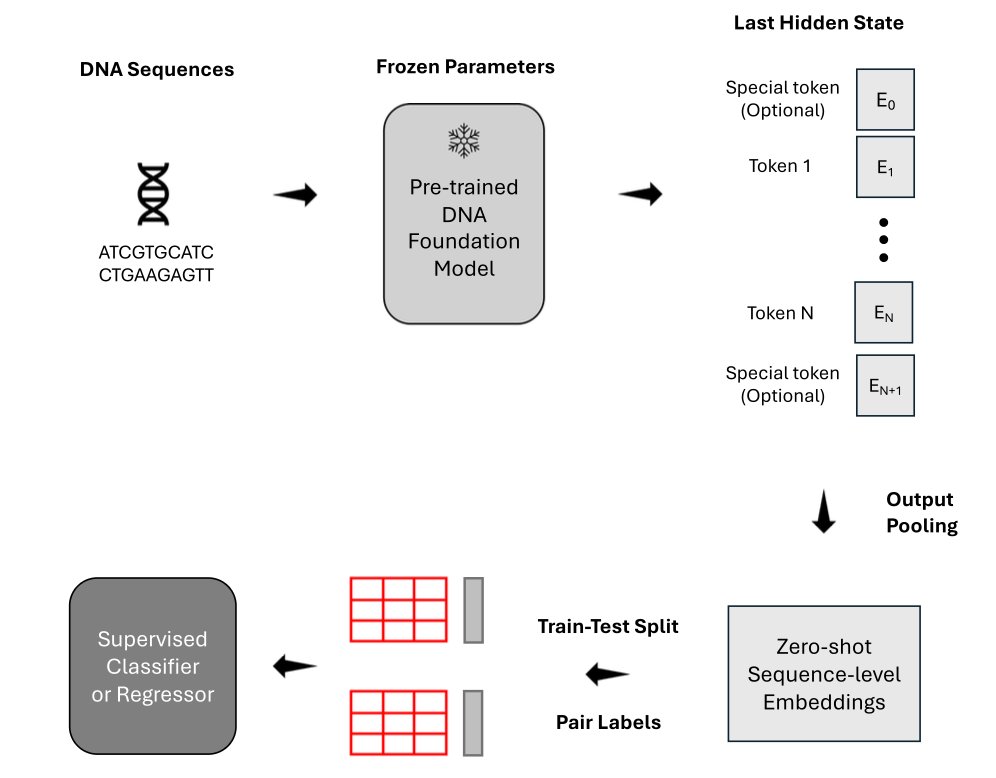

For downstream classification tasks, you need to convert a long DNA sequence into a vector. Many people are used to taking the model’s first output token (like BERT’s [CLS] token) to represent the whole sequence.

The data shows that mean token embedding works better. To understand the whole class, calculating the average grade (Mean Pooling) is more accurate than just asking the class president (Summary Token). This offers direct guidance for building model architectures.

The Awkwardness of a “Generalist”: A Jack of All Trades, Master of None

On high-level tasks like identifying pathogenic variants, the general-purpose foundation models perform reasonably well.

But when it comes to fine-grained quantitative tasks like predicting gene expression or detecting causal quantitative trait loci (QTLs), these large models lost to “old-school” specialized models optimized for the specific task. Today’s DNA foundation models have learned the grammar, but they don’t yet understand the biological regulatory logic behind the “semantics.” For drug target discovery, you can’t blindly trust a big model; sometimes, the low-tech methods work better.

Data Diversity is the Breakthrough

The authors retrained HyenaDNA on a multi-species dataset, and its performance improved significantly, with better generalization across species.

This makes sense from a biological perspective. Evolution is conservative, and regulatory mechanisms in mice, zebrafish, and even yeast are shared with humans. Giving the model data from diverse species is like a linguist learning Latin, French, and Spanish simultaneously—their ability to deduce the origins of English words naturally becomes stronger.

The Unseen 3D World

No matter how well they handle sequences, these models are almost completely “blind” to the 3D structure of the genome, such as topologically associating domains (TADs). They treat DNA as a one-dimensional string and don’t have an innate understanding of how it folds inside the cell nucleus. Chromatin folding directly determines gene expression.

Final Thoughts

In terms of computational efficiency, HyenaDNA scales well with long sequences, while Nucleotide Transformer V2 is a larger but stable model. The conclusion: DNA foundation models have a lot of potential, but they haven’t yet reached a “plug-and-play” stage where they disrupt everything. Training on multi-species data and fine-tuning for specific downstream tasks are necessary steps for practical use.

📜Title: Benchmarking DNA Foundation Models for Genomic and Genetic Tasks 🌐Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65823-8

5. OpenBioLLM: An Open-Source Multi-Agent Architecture Surpasses GeneGPT

GeneGPT once showed the potential of Large Language Models (LLMs) in biomedicine. OpenBioLLM now offers an alternative to GeneGPT’s monolithic architecture by building a team of “specialists.”

A Team of Specialists Working Together

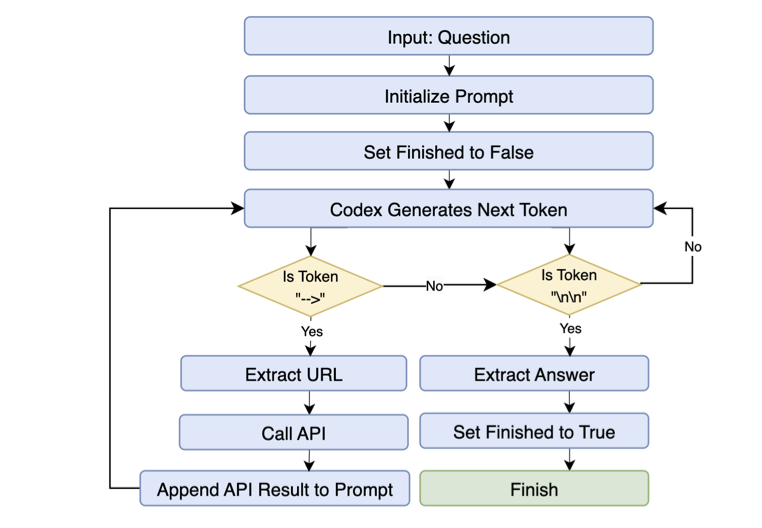

GeneGPT is like a do-it-all employee that has to handle intent recognition, API code writing, and result checking all at once. This is computationally expensive and prone to error. OpenBioLLM uses a multi-agent strategy, designing specific roles: a router agent to correctly dispatch questions, a query generator agent to write queries, and a validator agent to check for accuracy.

This division of labor works well. On the GeneTuring and GeneHop benchmarks, OpenBioLLM achieved average scores of 0.849 and 0.830, respectively. In over 90% of the tasks, its performance was equal to or better than GeneGPT’s.

Small Models and Role-Fit

OpenBioLLM uses open-source small models and doesn’t require extra fine-tuning, which challenges the “more parameters is always better” logic. By making agents focus on specific sub-tasks (making them “role-faithful”), it can avoid the reasoning shortcuts common in large models. In a specialized domain, role-fit is more critical than raw scale.

Speed and Flexibility

By breaking down complex genomic questions into parallel sub-tasks, system latency was reduced by 40% to 50%. The modular design also brings flexibility: integrating a new database or tool just requires adding a corresponding tool agent, without having to re-architect the system or retrain. This scalability is well-suited for the rapidly evolving field of genomics.

The authors analyzed the main sources of errors, which were incorrect API selection or improper parameter use, pointing the way for future improvements. This study shows that multi-agent collaboration is a better approach for solving complex scientific problems.

📜Title: Beyond GeneGPT: A Multi-Agent Architecture with Open-Source LLMs for Enhanced Genomic Question Answering 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.15061v1