Table of Contents

- An AI-designed protein binder blocks a key oxygen channel in [NiFe]-hydrogenase, tripling its oxygen tolerance and experimentally confirming for the first time the hierarchical structure of gas transport inside the enzyme.

- The FuncBind framework uses Neural Fields to represent different molecules as continuous atomic densities. This allows a single, unified model to generate small molecules, macrocyclic peptides, and antibody CDR loops, potentially breaking down the barriers between different drug modalities.

- The PGEL framework fine-tunes proteins in their embedding space to generate diverse and fully functional proteins.

- RTMol uses a “round-trip” learning mechanism to solve a persistent problem in AI: molecule-to-text translations that sound fluent but are structurally incorrect. It achieves true two-way consistency.

- The DADO algorithm breaks down complex design problems into smaller, manageable parts, opening a new path for AI-driven protein engineering and drug discovery.

1. AI Designs a Protein “Plug”: Tripling Hydrogenase Oxygen Tolerance

[NiFe]-hydrogenase is a key molecule in bioenergy because it produces hydrogen efficiently. But it’s extremely sensitive to oxygen—even tiny amounts can “poison” its active core and shut it down. Traditional methods to modify the enzyme often hurt its performance more than they help.

A research team decided to build an “add-on” for it. They used AI to design a protein binder from scratch, one that acts like a plug to block the channel oxygen uses to get in.

How AI Designed the “Molecular Plug”

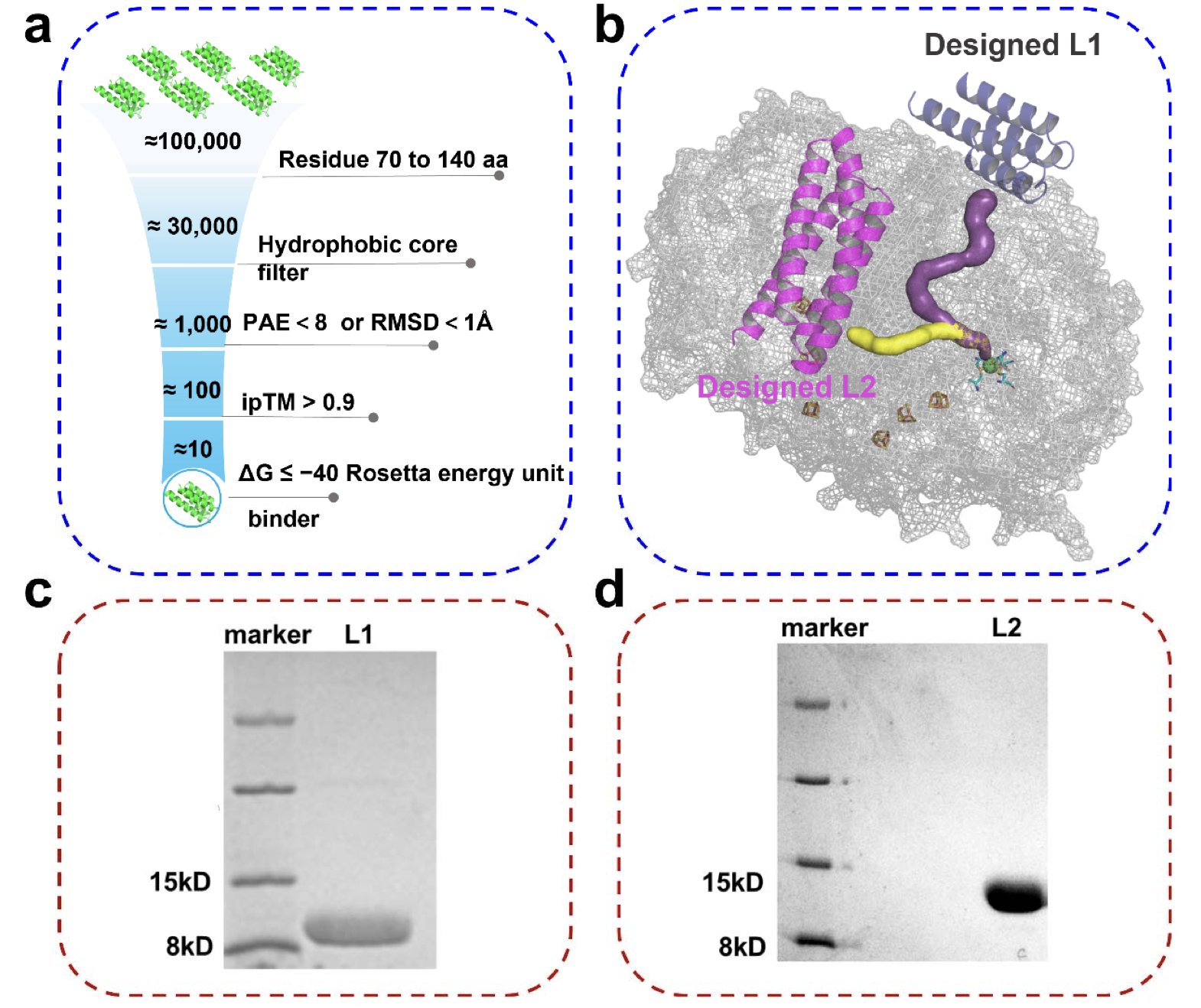

The team used a trio of AI tools: RFdiffusion to generate the backbone, ProteinMPNN to design the sequence, and AlphaFold to predict the structure. Out of about 100,000 candidates, they selected two high-affinity binders, L1 and L2.

These two binders were designed to target different predicted gas channels.

Solving the Gas Channel Mystery

L1 was designed to block “channel 1” and L2 to block “channel 2.” The experiments showed that hydrogenase bound with L1 was over three times more stable in the presence of oxygen. The enzyme bound with L2 showed almost no change in oxygen tolerance.

This result settled a long-standing debate about how gas gets into the hydrogenase. Crystal structures alone don’t show this dynamic process. The “block-and-lock” strategy provided direct evidence: Channel 1 is the main route for oxygen, while channel 2 contributes very little to oxygen transport.

A Hydrophobic Cavity that Acts Like a Gatekeeper

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations showed that L1 creates a hydrophobic cavity at the channel’s entrance, acting like a molecular gatekeeper. When oxygen molecules try to enter, they get temporarily trapped in this hydrophobic environment. This dynamic blockage slows oxygen from reaching the enzyme’s active center but still allows the enzyme to function.

This work demonstrates a general method: using AI to design precise protein tools to probe the mechanisms of complex metalloenzymes. Compared to traditional mutagenesis, this approach is less disruptive and provides more convincing results.

📜Title: De Novo Design of a Protein Binder to Probe Gas Channel and Enhance the Oxygen Tolerance of [NiFe] Hydrogenase 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.19.689374v1

2. Neural Fields for Unified Molecule Generation: A Unified Theory for AI Drug Design?

Core Idea:

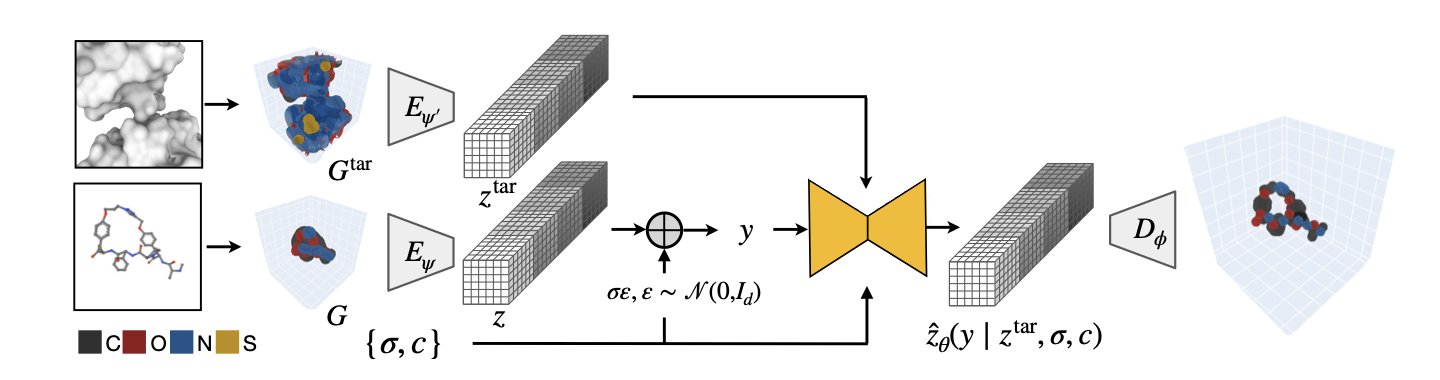

In drug discovery, molecules are typically grouped into classes like small molecules, peptides, and antibodies. Each class has its own design rules and computational models. Researchers from MIT and Genentech developed the FuncBind framework to try and generate all these different types of molecules with a single, unified approach.

The core technology is neural fields. Traditional methods define a molecule by the precise coordinates of each atom. Neural fields, however, treat the entire molecule as a continuous cloud of atomic density. The densest spots in the cloud are where the atomic nuclei are located.

This way of representing molecules blurs the lines between different molecular types. From the perspective of a neural field, a small molecule, a macrocyclic peptide made of amino acids, or even a larger antibody protein are all just distributions of atomic density. This allows researchers to use a single generative model to train on and design all of them, as if they found a common grammar for different molecular languages.

The model performed well in tests. Computer simulations showed that the quality of the small molecules, macrocyclic peptides, and antibody Complementarity-Determining Region (CDR) loops it generated was comparable to specialized models designed for each specific molecule type.

For experimental validation, the researchers took a known antibody-target protein complex and had FuncBind redesign its most critical component, the CDR H3 loop. In lab experiments, the newly designed antibody was able to bind to the target. This shows FuncBind can design new molecules with real-world function.

The work also contributes a new dataset of about 190,000 structures of synthetic macrocyclic peptide-protein complexes. Macrocyclic peptides are an emerging class of drugs that fall between small molecules and antibodies. Data on them is scarce, so this dataset should help advance the field.

FuncBind’s unified view of molecule generation using neural fields opens a new path for cross-modality drug design. It’s still early, but this approach could one day be extended to larger biological systems or even be used to design “hybrids” between different molecular types.

📜Title: Unified All-Atom Molecule Generation with Neural Fields 🌐Paper: https://openreview.net/pdf/6635b183138e1f0d25dfd02911c6d87234a8b01e.pdf

3. PGEL: Precisely Controlling Protein Design in Embedding Space

Protein design often presents a dilemma: you want to create new proteins but must keep their most critical functional parts, like the active site of an enzyme or the binding epitope of an antibody. It’s like redesigning a key. You can change the handle’s shape, but the teeth that open the lock have to be perfect.

Existing methods like RFdiffusion use a local diffusion strategy. This is like welding the key’s teeth in place and letting the model freely design around them. The results aren’t ideal. Either the generated structures are too similar to the original to accommodate the fixed part, which limits diversity, or the connection between the new and old parts is messy and structurally unsound, which limits designability.

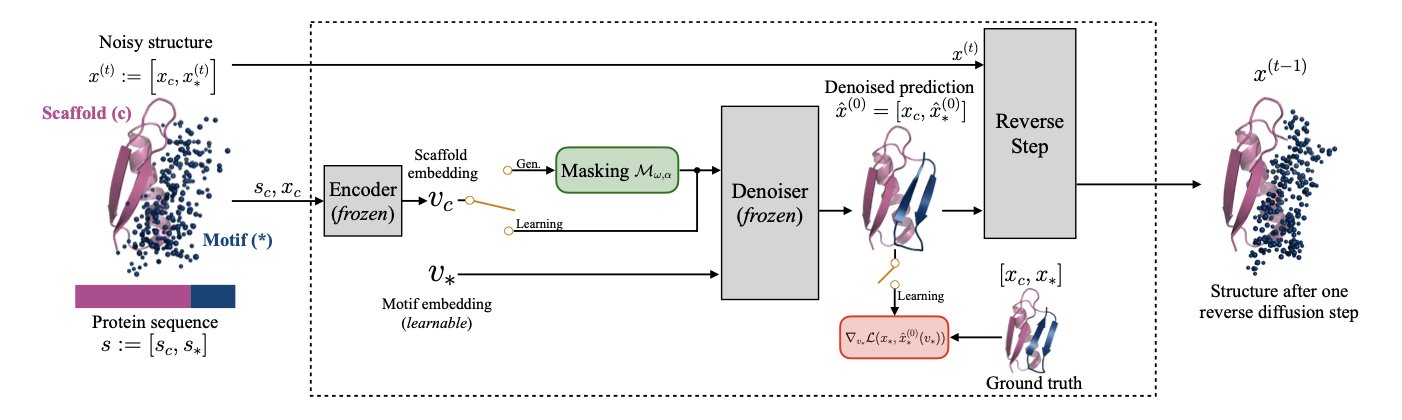

The PGEL (Protein Generation with Embedding Learning) framework takes a different approach: it solves the problem in a higher-dimensional embedding space.

Here’s how it works.

First, it uses a technique from image generation called “textual inversion.” A protein’s functional motif can be seen as a unique “concept” or “word,” like “p53 binding interface.” PGEL learns a mathematical representation for this “word”—a high-dimensional vector, or “embedding,” that captures its sequence and structural information.

The next step is key. PGEL makes small, controlled “perturbations” directly to this learned embedding vector. This is like adjusting a photo in editing software. You aren’t changing the RGB values of millions of pixels; you’re moving sliders for “brightness” and “contrast.” Working in the embedding space is like finding the “sliders” that control a protein’s properties. Each small adjustment represents a biologically plausible exploration of the functional motif.

Finally, the tweaked embedding vector is given as a new “prompt” to a protein diffusion model, which generates a complete, new protein. Because the “prompt” itself contains the essence of the functional motif, the new protein preserves the core function while having the desired diversity in its overall structure.

The researchers tested PGEL on three representative cases: a single protein (calmodulin), a protein-protein binding site (barnase-barstar), and a cancer-related transcription factor complex (p53-MDM2). The results showed that in each case, the library of structures generated by PGEL was superior in diversity and designability to those from traditional local diffusion methods.

Take the classic protein-protein interaction (PPI) target p53-MDM2. The goal in drug development is to find small molecules or peptides that can block this interaction. With PGEL, researchers can start with a known binding motif and generate thousands of new protein or peptide scaffolds that retain the core binding ability. This expands the search space for lead compounds and increases the chances of finding drug candidates with high affinity and good drug-like properties.

This method elevates protein design from “atomic-level” tinkering to “conceptual-level” control. It’s an advance in technology and a shift in thinking. We are a step closer to a future where we can design proteins as easily as we edit text.

📜Title: Protein Generation with Embedding Learning for Motif Diversification 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.18790

4. RTMol: Breaking Illusions to Achieve Accurate Two-Way Alignment Between Molecules and Text

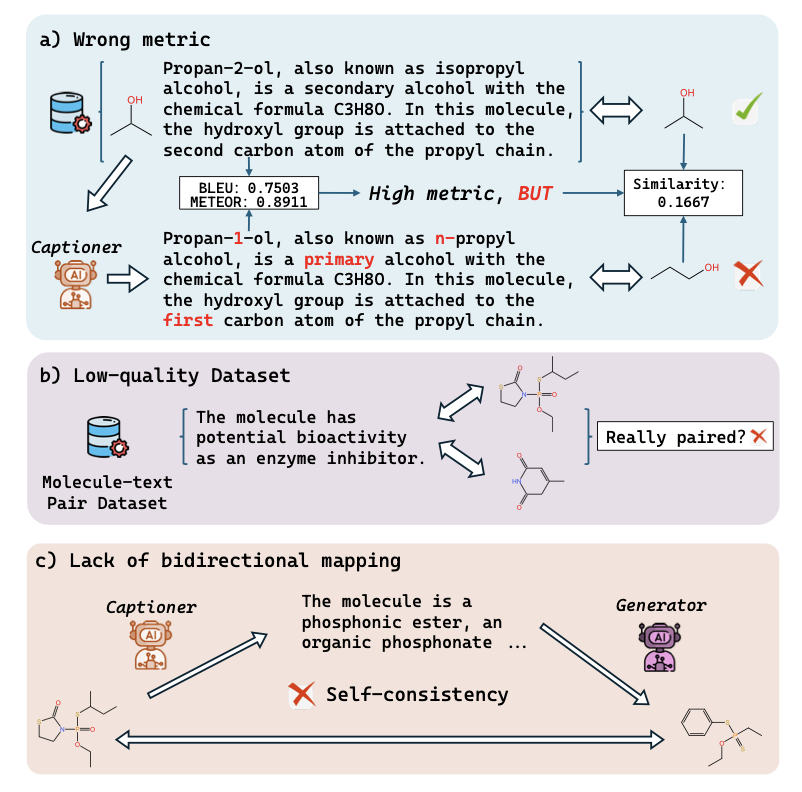

Computational chemists and drug developers often face a frustrating problem. Current AI models, whether general ones like ChatGPT or specialized Mol-LLMs, can describe a molecule with perfect grammar and elegant phrasing. But when you check the structure they describe, it’s full of mistakes. A missing methyl group or the wrong ring size is common.

RTMol aims to solve this core problem.

Current evaluation systems rely too much on Natural Language Processing (NLP) metrics like BLEU or ROUGE. In NLP, “apple” and “fruit” are semantically close. But in chemistry, a benzene ring and a pyridine ring differ by just one atom, yet their properties are completely different. Traditional metrics focus on text overlap and can’t catch this kind of “chemical distortion.”

RTMol introduces a “round-trip” perspective.

It’s like checking accuracy with Google Translate: you translate from Chinese to English, then back to Chinese. If the meaning has changed, the translation is flawed. RTMol applies this logic to molecules:

- Molecule-to-Text: The model looks at a molecule’s structure and generates a description.

- Text-to-Molecule: The model tries to reconstruct the structure based on the description it just wrote.

- Compare: The reconstructed molecule is checked against the original to see if they match.

This is more than just an evaluation metric; it’s a training framework. The same Large Language Model plays two roles: the Captioner and the Generator.

The system uses reinforcement learning, with the reward signal tied directly to “chemical fidelity.” The model only gets a reward if the sentence it generates can be used to reconstruct the correct structure. This forces the model to focus on the key features that define a molecule’s properties, not just on writing eloquent text.

High-quality, aligned molecule-text data is scarce, and public datasets often have noise or incomplete annotations. RTMol’s self-supervised training allows the model to correct itself using its own internal consistency, reducing its reliance on perfect datasets.

Experiments showed significant improvements in two-way alignment performance across several Large Language Models, with round-trip consistency increasing by up to 47%.

For drug development, this means that future AI assistants will be able to truly “read” a structure. When we provide a complex pharmacophore description, the molecular structure it generates will be reliable. This is what AI-assisted drug design should look like.

📜Title: RTMol: Rethinking Molecule-text Alignment in a Round-trip View 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.12135v2

5. DADO: A Smart Solution for Complex Design, a New Path for AI Drug Discovery

Drug discovery, especially in protein engineering, faces a huge challenge: the number of possible molecular combinations is astronomical. For example, changing just a few amino acids in a protein can create more combinations than there are atoms in the universe. Traditional screening methods are like searching for a needle in a haystack.

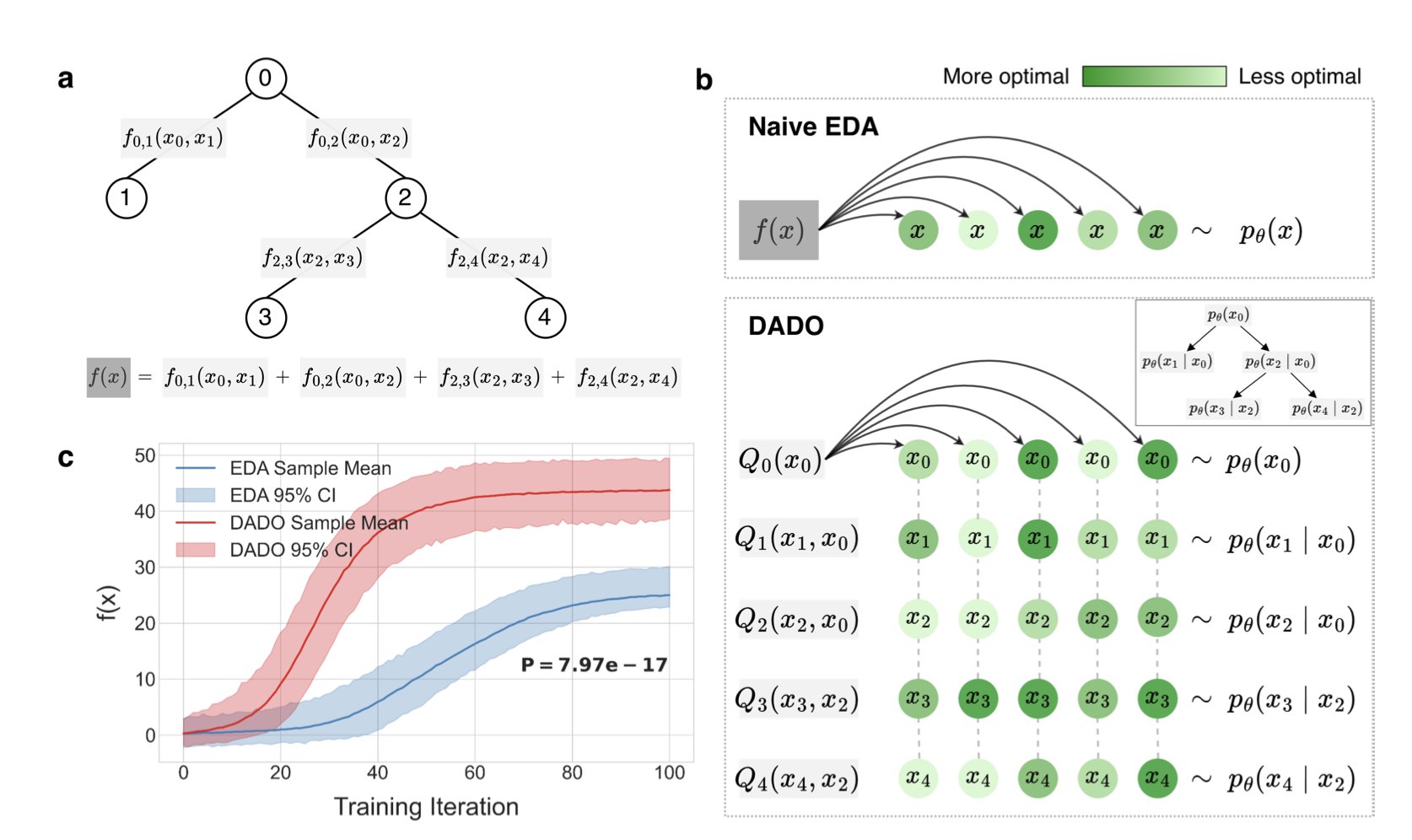

AI has changed the field, but even with AI, searching for the best molecule in such a vast “solution space” can be overwhelming. Traditional Estimation of Distribution Algorithms (EDAs) are not very efficient at handling these discrete, highly structured problems. They try to optimize all variables at once, and the computational cost explodes when the variables are interconnected.

The DADO (Decomposition-Aware Distributional Optimization) algorithm offers a clever solution. Its core idea can be explained with an analogy. If you’re assembling a complex machine, is it easier to pile all the parts together and hope for the best, or to assemble components (like the engine and chassis) separately and then put them together? The answer is obvious.

DADO does something similar. It first analyzes the “decomposability” of the problem—whether a molecule’s overall property (like its activity) can be seen as the sum of the properties of its local structural parts. Many scientific problems, including protein design, fit this description. A protein’s final function largely depends on the local functions of its individual domains.

Once it identifies this structure, DADO uses a graph structure called a “junction tree” to break the entire design space down into a series of smaller, interconnected subproblems. It then optimizes within these subspaces separately by passing messages along the tree structure. Finally, it combines the best solutions from each part to get the optimal overall design.

This “divide and conquer” strategy reduces computational complexity. It means you can optimize one functional domain, then another, while considering their interactions, without having to consider all possible combinations of all amino acids in the protein at once.

The researchers tested DADO’s effectiveness on both synthetic datasets and real protein design tasks. The results showed that compared to traditional EDA algorithms, DADO found protein sequences with the target properties faster and more accurately, showing its potential for solving real-world problems.

From a research scientist’s perspective, DADO’s value is that it provides a computational framework that aligns better with chemical intuition. It incorporates knowledge of the problem’s internal structure (decomposability) into the algorithm’s design. This improves efficiency and also makes the AI’s decision-making process more transparent and interpretable.

In the future, DADO could be combined with other AI technologies like more advanced generative models or policy optimization algorithms, potentially playing an even larger role in fields like drug design and new materials discovery.

📜Title: Leveraging Discrete Function Decomposability for Scientific Design 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.03032v1