Table of Contents

- MergeDNA adapts to genomic complexity with a dynamic tokenization strategy, outperforming existing SOTA models on multi-omics tasks.

- A new hybrid deep learning framework incorporates atomic hybridization and traditional molecular descriptors, overcoming the GNN limitation of not capturing global physicochemical properties.

- PepBFN uses a Riemannian–Euclidean Bayesian Flow Network to model sequence and structure in a fully continuous parameter space, solving the multimodal distribution problem of side-chain rotamers.

- SSRGNet combines a sequence language model with a 3D spatial graph network, using multi-relational edges and a parallel fusion strategy to improve protein secondary structure prediction.

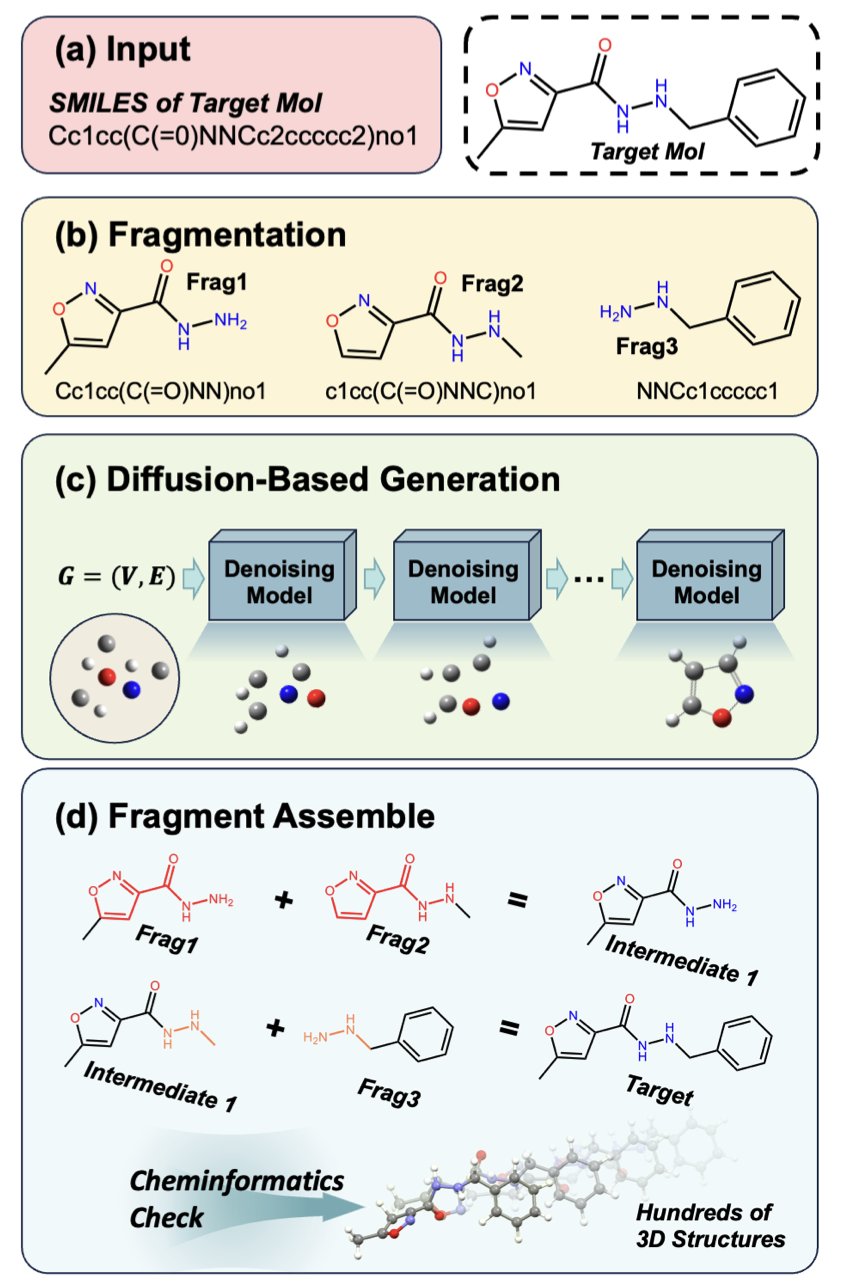

- StoL tackles the lack of training data for large molecule conformation generation by breaking molecules into fragments, generating their 3D structures with diffusion models, and then reassembling them.

1. MergeDNA: A Dynamic Tokenization Breakthrough for Genome Modeling

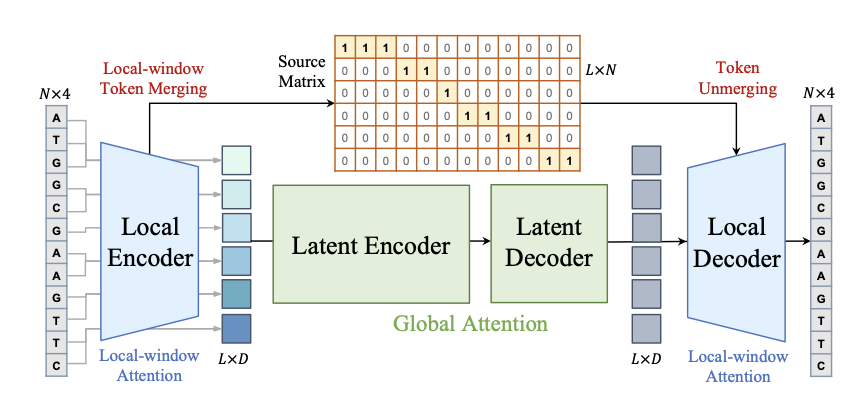

Existing DNA Foundation Models often struggle because they are heavily influenced by human language models. Common methods like k-mer or Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) can’t handle the highly uneven information density of the genome. A single base change in a dense coding region is critical, while long repetitive sequences contain very little information. Using the same tool to measure both is not effective.

MergeDNA introduces a layered architecture that acts like a “zoom lens.” It uses a Local Encoder with a differentiable Token Merging technique to solve this problem.

When the model encounters highly repetitive, low-information sequences, it automatically merges tokens, essentially skimming through them. But for complex regions like promoters or exons, it keeps tokens fine-grained for a detailed reading. This dynamic adjustment captures short-range motifs while efficiently handling long-range dependencies.

Training this architecture relies on two key pre-training tasks: 1. Merged Token Reconstruction: The model must reconstruct the merged tokens, forcing it to understand the context of the compressed regions. 2. Adaptive Masked Token Modeling: An advanced version of masked language modeling that adaptively filters important tokens for prediction.

MergeDNA achieves state-of-the-art (SOTA) results on multiple DNA benchmarks and multi-omics tasks. It outperforms larger traditional models on difficult tasks like cross-species generalization, RNA splicing site prediction, and zero-shot protein fitness prediction.

For computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) and synthetic biology, this provides a higher-resolution tool. The model goes beyond mechanical base-pair statistics and starts to identify the real signals and noise within the genome.

📜Title: MergeDNA: Context-aware Genome Modeling with Dynamic Tokenization through Token Merging

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.14806v1

2. Atomic Hybridization Empowers GNNs for More Accurate Drug Target Prediction

Giving AI a Chemist’s Eyes

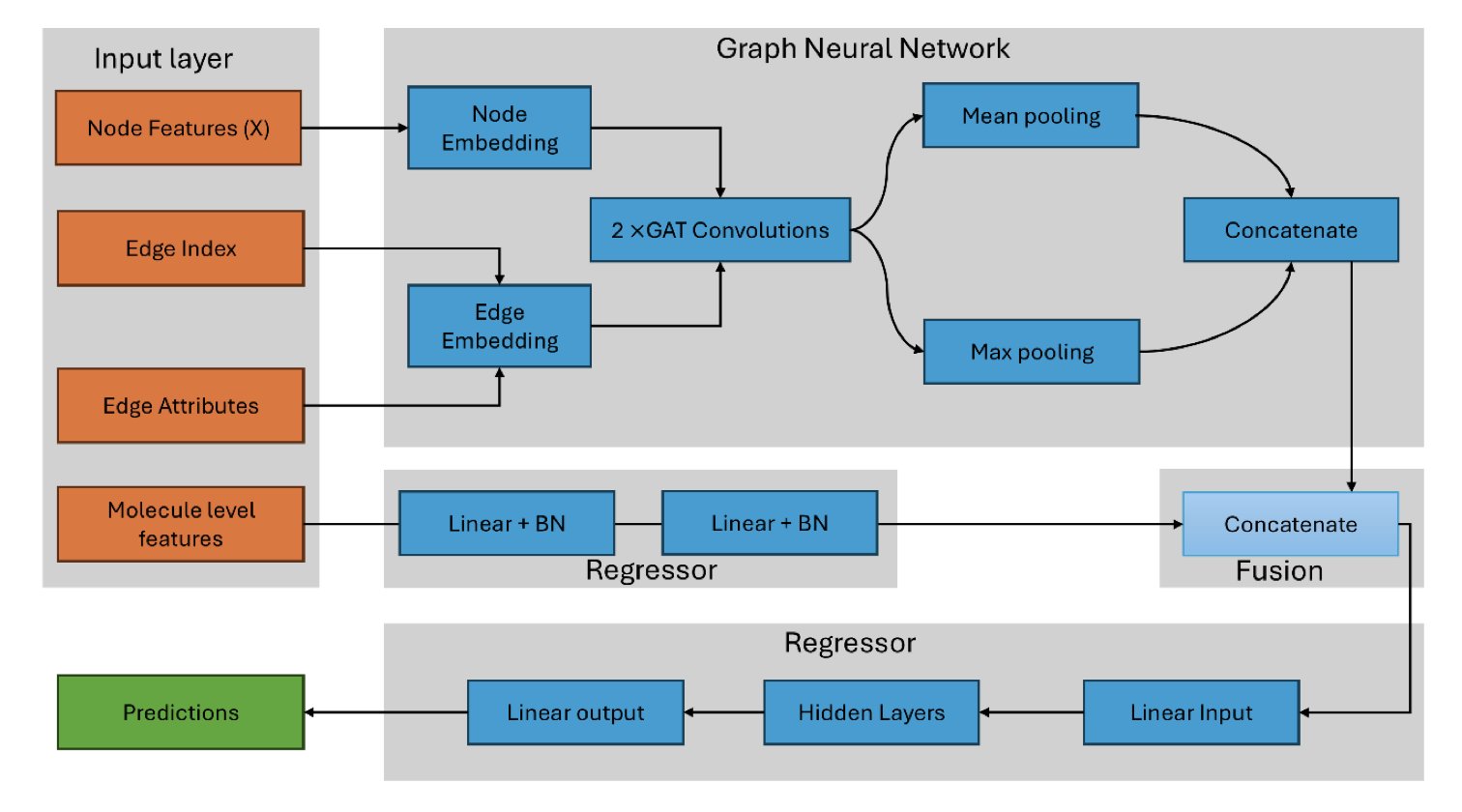

Computer-aided drug discovery often simplifies molecules into 2D graphs where atoms are just nodes, ignoring deeper chemical properties. But to a medicinal chemist, a carbon in a benzene ring (sp2 hybridized) is completely different from a carbon with four single bonds (sp3 hybridized). Their spatial arrangement, electron cloud distribution, and reactivity are distinct.

This research develops a Graph Neural Network (GNN) model based on atomic hybridization. The model looks beyond basic atom types to understand electron configurations and spatial orientations. This approach allows the algorithm to perceive a molecule’s local structure at the electronic level, just like a chemist would.

Combining Old and New: GNNs Meet Molecular Descriptors

A pure GNN model tends to focus too much on local connections, sometimes missing global properties like the partition coefficient (logP) or molecular weight. To address this, the researchers designed a hybrid architecture. One branch uses a GNN to process the local structure, while another handles classic molecular descriptors.

This is like evaluating a drug molecule by both examining its functional groups under a microscope and checking its overall physicochemical stats. This synergy improves prediction accuracy and maintains interpretability—we can see which physical and chemical properties are influential.

Data and Results: A Clear Improvement

The researchers trained the model on 14,316 compounds across 9 biological targets. The test set R² reached 0.87, with performance improving by 6% to 42% compared to previous methods. The model showed excellent IC₅₀ prediction for highly druggable targets like kinases and nuclear receptors.

Multi-target joint training is another key feature. To address the problem of data scarcity for new targets, the model allows knowledge transfer between different protein families. Patterns learned from data-rich targets can help predict outcomes for data-poor ones. This is very useful for orphan receptors with limited activity data.

The framework’s potential could be further expanded by incorporating 3D conformational information or by fine-tuning with large-scale pre-trained models.

📜Title: Graph Neural Networks Model Based on Atomic Hybridization for Predicting Drug Targets

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.19.689219v1

3. PepBFN: Reshaping Full-Atom Peptide Design with Bayesian Flows

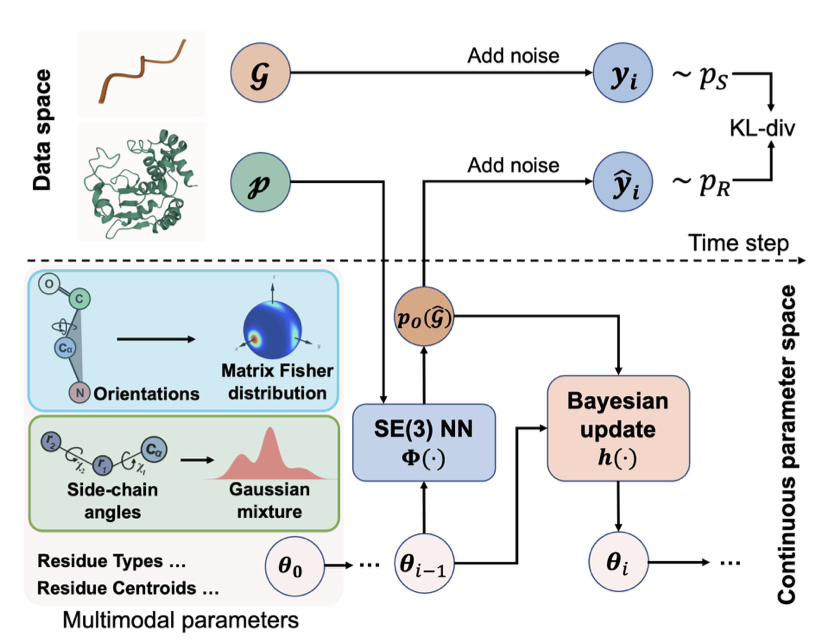

Peptide design has long faced a challenge: it’s hard to coordinate discrete amino acid sequences with continuous 3D structural coordinates. PepBFN introduces Bayesian Flow Networks (BFNs) to address this problem in a mathematically elegant way.

A Fully Continuous Parameter Space

Traditional diffusion models lose information when they add and remove noise from discrete sequences. PepBFN places both sequence and structure into a fully continuous parameter space. This is like converting a digital signal to an analog one, giving it a smoothness and coherence that discrete models can’t match when capturing subtle changes.

Capturing Side-Chain Dynamics

Amino acid side chains aren’t fixed; they exist as rotamers, like a switch with multiple positions. Traditional models often assume side chains follow a single-peak Gaussian distribution, which is physically unrealistic. PepBFN uses a Gaussian mixture-based Bayesian flow to accurately identify the multiple potential stable states of a side chain in space, instead of just averaging them. This ability to capture multimodal properties improves side-chain prediction accuracy.

Proper Geometry on the SO(3) Manifold

Calculating protein backbone orientation using Euclidean geometry can easily lead to errors that require constant correction. This model works directly on the SO(3) manifold, using a Riemannian flow based on the Matrix Fisher distribution. This mathematical language, designed for rotations, makes Bayesian updates easy to compute. Changes in residue orientation are mathematically continuous, so no extra geometric constraints are needed to prevent the structure from falling apart.

Performance in Practice

These theoretical advantages translate into real performance. PepBFN has set new records on tasks like side-chain packing, reverse folding, and the difficult task of binder design. By correctly mapping biophysical properties—like rotamer diversity and non-Euclidean geometry—into the mathematical model, the accuracy of computer-aided drug design takes a leap forward.

📜Title: Full-Atom Peptide Design via Riemannian–Euclidean Bayesian Flow Networks

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.14516

4. SSRGNet: 3D Graph Neural Networks and Large Language Models Join Forces for Protein Structure Prediction

- Dual-Encoding Mechanism: Uses DistilProtBert to process sequence information and a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN) to handle 3D structural features.

- Multidimensional Relationship Modeling: Builds a protein graph with three types of edges—sequential, spatial, and local environment—to capture complex folding patterns.

- Parallel Fusion Advantage: Parallel fusion preserves the complementary nature of multimodal information more effectively than serial or cross fusion.

- Performance Validation: Achieves higher accuracy than current leading methods on benchmark datasets like CB513, TS115, and CASP12.

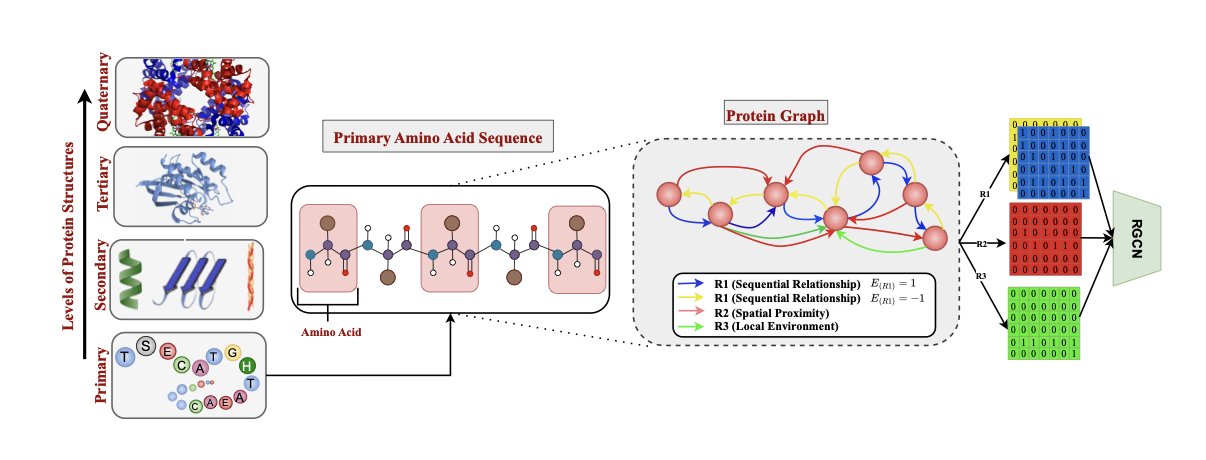

The field of protein structure prediction is merging Large Language Models (LLMs) from natural language processing (NLP) with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that handle geometric structures. SSRGNet shows the power of combining the “reading” of amino acid sequences with the “observation” of 3D topology.

Considering Both Sequence and Shape

A protein is fundamentally a spatial structure, and focusing only on its sequence misses key spatial information. SSRGNet uses DistilProtBert to extract contextual meaning from the sequence while building a 3D protein residue graph to capture spatial geometric features with a GNN.

Defining Residues with Three “Relations”

Instead of simply connecting adjacent residues, the model uses three different types of “edges” to describe their relationships: 1. Sequential Edges: Focus on adjacent amino acids in the sequence. 2. Spatial Edges: Connect amino acids that are far apart in the sequence but close in 3D folded space, capturing long-range interactions. 3. Local Environment Edges: Describe the features of a residue’s microenvironment.

Using Relation-Aware Message Passing, the model can analyze the combined influence of an amino acid’s identity, position, and its immediate surroundings.

A Parallel Fusion Strategy

When dealing with both sequence and structure data, parallel fusion works better than serial or cross fusion. This approach allows sequence and structural features to be processed independently before being combined for a final judgment, preserving the maximum amount of complementary information from both modalities.

Results and Applications

Tests on datasets like CB513 and CASP12 confirm the model’s effectiveness. Ablation studies proved that all three types of relational edges are essential for its performance. Future plans include pre-training on more external structural datasets. For drug design or enzyme engineering, a model that can finely interpret local protein geometry has significant practical value.

📜Title: Protein Secondary Structure Prediction Using 3D Graphs and Relation-Aware Message Passing Transformers

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.13685v1

5. StoL: Building 3D Conformations of Large Molecules with Diffusion Models, Like LEGOs

Drug development starts with an accurate 3D structure of a molecule. For small molecules, data is plentiful and the process is straightforward. But for large molecules, high-quality 3D training data is extremely scarce, and end-to-end deep learning models often perform poorly.

A study called StoL (Small-to-Large) takes a different approach. If there isn’t enough data for large molecules, it breaks them down and uses the strengths of small-molecule methods to solve the problem.

Assembling Molecules Like Building Blocks

StoL’s logic is intuitive and effective. It takes a complex, long-chain molecule and cuts it along rotatable single bonds, breaking it into chemically sensible, rigid fragments.

This transforms the difficult problem of predicting a large molecule’s complex fold into several simpler, local 3D generation tasks. Existing diffusion models, which are well-trained on small-molecule data, can handle these fragments easily. The system then reassembles the generated 3D fragments based on their connection points. This method successfully bypasses the hurdle of insufficient large-molecule data.

Injecting “Chemical Common Sense”

A purely data-driven approach can lead a model to make basic mistakes, like twisting an aromatic ring that should be flat. To prevent this, StoL includes a “chemistry-enhanced” training stage.

The model first learns the general shape of molecules from a large dataset. Then, it enters a second phase of specialized training on physicochemical rules. This forces the model to obey fundamental principles like correct bond lengths, bond angles, and planarity. The final structures are not only geometrically sound but also have much greater energy stability.

Searching Beyond RDKit

The widely used tool RDKit is fast, but it can get stuck in local energy minima and fail to find the lowest-energy natural state.

StoL performs much better here. When validated against density functional theory (DFT), the gold standard in computational chemistry, the conformations generated by StoL consistently have lower energy. This means it can explore a wider chemical space and find realistic molecular poses that traditional methods might miss. This advantage is critical for designing drugs that need to fit precisely into a protein’s binding pocket.

Limitations and Lessons

StoL isn’t perfect. It still struggles with complex fused-ring systems that are difficult to cut into simple pieces. But it is a clever advance in computational chemistry, showing an effective way to solve a complex problem: break it down into simpler ones we already know how to solve.

📜Title: Chemistry-Enhanced Diffusion-Based Framework for Small-to-Large Molecular Conformation Generation

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.12182v1