Table of Contents

- Chem-R mimics a chemist’s thinking to fix logical fallacies in large language models for chemistry, turning AI from a “knowledge base” into an “R&D partner.”

- The effectiveness of fine-tuning a large language model depends on the identifiers it learns. If the identifiers are meaningful (like gene names), the model can generalize. If they are arbitrary codes (like ontology IDs), it just memorizes.

- CryoDyna turns static snapshots from cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) into a high-definition movie of protein dynamics, directly reconstructing continuous conformational changes at near-atomic resolution from 2D images.

- In drug molecule generation, increasing the structural diversity of training data produces more high-quality and varied hit compounds than just increasing model parameters or data size.

- MolEdit uses multi-expert adapters and a smart switch to update knowledge in multimodal molecular language models with high precision, solving the problems of costly retraining and “catastrophic forgetting” caused by fine-tuning.

1. Chem-R: Teaching AI to Reason Like a Chemist

Existing Large Language Models (LLMs) often give wrong answers that look professional when solving chemistry problems. They can recite reactions from a textbook, but if you give them a new molecule, they might design a synthesis route with a carbon atom that has five bonds. This shows that the models have learned the language of chemistry but not the physical laws and logic behind it.

The Chem-R model was designed to fix this. The idea is straightforward: teach the AI to think like a trained chemist.

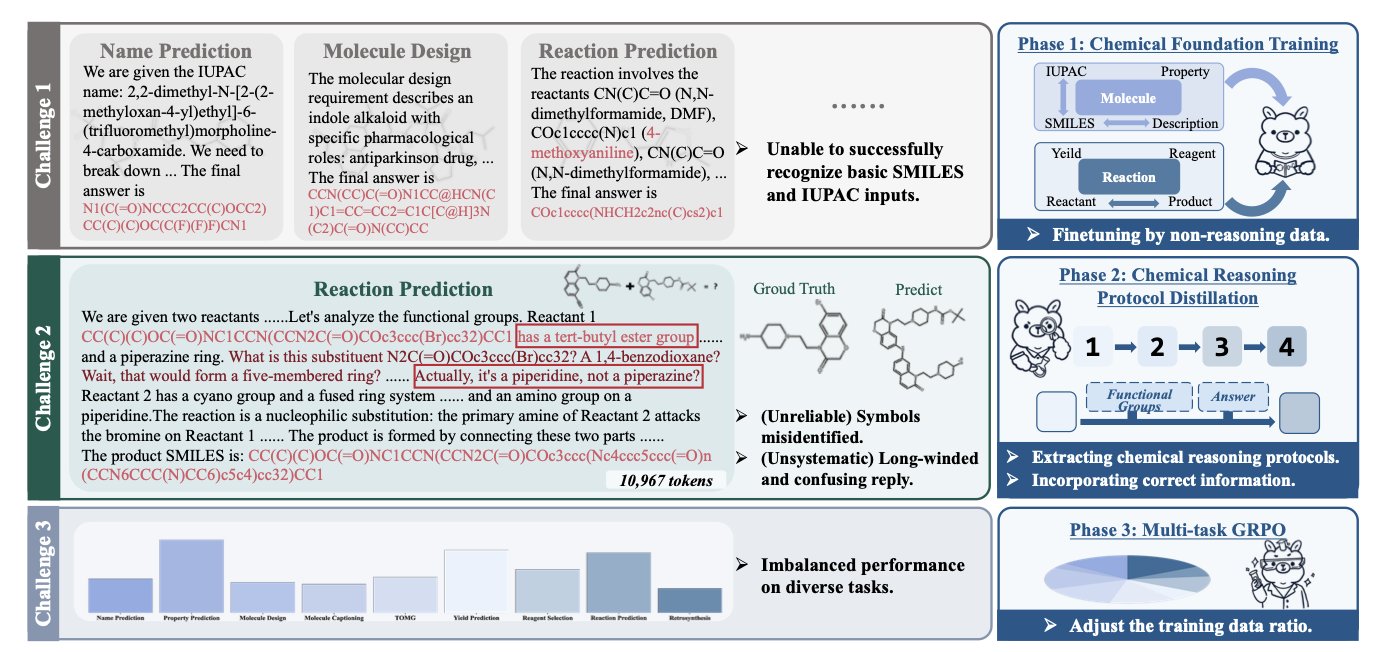

It works in three steps.

First, Chemical Foundation Training. This is like sending the AI to a basic chemistry class. The model is first fine-tuned on a massive amount of non-reasoning data, like molecular structures and chemical reactions. The goal is to make it master the basic language of chemistry, such as how to write SMILES strings and the structure of functional groups, to avoid simple mistakes like the “five-bond carbon.” This is the foundation for reliable reasoning.

Second, Chemical Reasoning Protocol Distillation. This is the core of Chem-R. When humans solve chemistry problems, they follow a certain thought process. For example, in retrosynthesis, we first identify key functional groups, look for bonds that can be broken, propose possible synthons, and then match them to corresponding building blocks. Chem-R learns this thinking “protocol.” By mimicking the high-quality, step-by-step reasoning generated by a more powerful “teacher model,” its output is no longer a black-box answer but a logical, verifiable thought process.

Third, Multi-task Group Relative Policy Optimization. A good chemist needs to understand both reaction prediction and molecular properties. This step ensures the model doesn’t become too specialized. Using a special optimization strategy, the model’s performance on molecule-level tasks (like property prediction) and reaction-level tasks (like product prediction) is balanced. This prevents the model from getting too good at one task at the expense of others, making it a more well-rounded “chemist.”

Chem-R performed 46% to 66% better on molecule- and reaction-related tasks than general large models like Gemini-2.5-Pro and DeepSeek-R1. It also outperformed other models designed specifically for chemistry.

Human chemistry experts also evaluated the reasoning processes generated by Chem-R. The results showed that Chem-R received the highest scores on multiple criteria, including the accuracy of chemical knowledge, logical coherence, and expert insight. This means the model’s problem-solving approach was recognized by professional peers.

In drug development, AI might soon go from being a “librarian” that looks up data in papers to a “virtual colleague” that can discuss synthesis routes, analyze molecular activity, and suggest optimizations. When AI understands “what,” “why,” and “how,” it can truly contribute creatively to drug development. Chem-R isn’t perfect, but it points in the right direction: teach AI to think like an expert, not just mimic language.

📜Title: Chem-R: Learning to Reason as a Chemist 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.16880

2. The Secret to AI Fine-Tuning: When Does a Model Memorize vs. Truly Learn?

We want Large Language Models (LLMs) to be research assistants, not just parrots that can recite facts. In biomedicine, a tedious but fundamental task is term normalization—accurately mapping a term like “heart attack” to a standard identifier like MeSH ID D009203. If an AI could truly understand these terms, it would greatly speed up research.

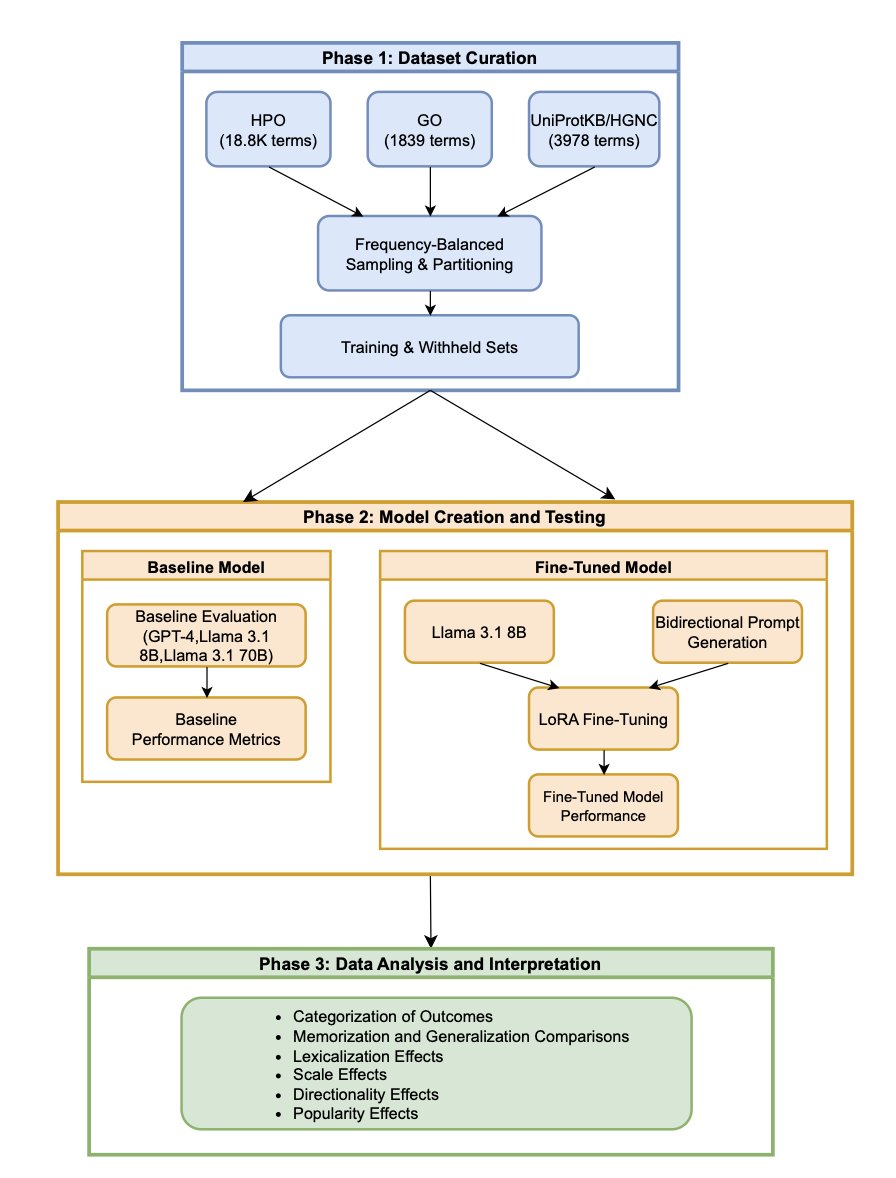

A paper explored whether fine-tuning teaches an LLM to “understand” or just “memorize.” Researchers used the Llama 3.1 8B model to recognize three biomedical term systems: the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), the Gene Ontology (GO), and protein-to-gene symbol mapping.

The results were stark.

For GO and HPO, fine-tuning improved the model’s accuracy on the training data, but it was just rote memorization. When faced with new terms it hadn’t seen, the model was helpless. This is called “Memorization.”

But for the protein-to-gene symbol mapping task, the model not only remembered the training data but could also accurately handle protein-gene pairs it had never seen before. This is the “Generalization” ability we want, showing that the model learned a rule.

There are two reasons for this difference: identifier popularity and identifier lexicalization.

“Popularity” refers to how often a term-identifier pair appears in the pre-training data. The more the model has seen it, the better it remembers, and the more effective fine-tuning is.

The key is “Lexicalization.”

Lexicalized identifiers contain semantic information themselves. For example, the gene symbol TP53 is associated with concepts like “tumor suppressor” and “cell cycle” in a vast amount of text. During pre-training, the model has already built a semantic network for TP53. Fine-tuning then connects this existing network to the new term. With this semantic “scaffolding,” the model can apply what it learns to new situations.

In contrast, identifiers like HPO:HP:0001250 (Seizure) or GO:0008150 (biological_process) are “non-lexicalized.” They are arbitrary strings that carry no biological meaning. The model can only memorize the mapping “if input is A, then output is B.” This kind of memory is fragile and fails when it encounters new terms.

It’s like teaching someone who knows a lot about fish to recognize a “grouper.” They can learn quickly and even infer what other similar fish look like. But if you give them a randomly coded card and tell them it means “grouper,” they learn nothing except to memorize that one card.

The study had two other findings: - If an identifier never appeared in the pre-training data, fine-tuning won’t work. The model has no semantic foundation to build on. - For lexicalized identifiers, more fine-tuning data helps the model generalize better. For non-lexicalized ones, more data just means more to memorize.

So, before fine-tuning a model for term normalization, first determine whether your target identifiers are meaningful words like TP53 or arbitrary codes like GO:0008150.

The answer will determine whether your model becomes an assistant or just a clumsy parrot.

📜Title: From Memorization to Generalization: Fine-Tuning Large Language Models for Biomedical Term-to-Identifier Normalization 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.19036

3. CryoDyna: Turning Cryo-EM Stills into a Dynamic Movie of Proteins

Proteins are dynamic, and the beautiful structures captured by cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) are just static snapshots of their motion. It’s hard to understand how an engine works from a single still photo, and the same is true for proteins. To understand a target’s function and how drugs interact with it, we need to see it in motion. The CryoDyna tool was designed for this purpose.

How does it work?

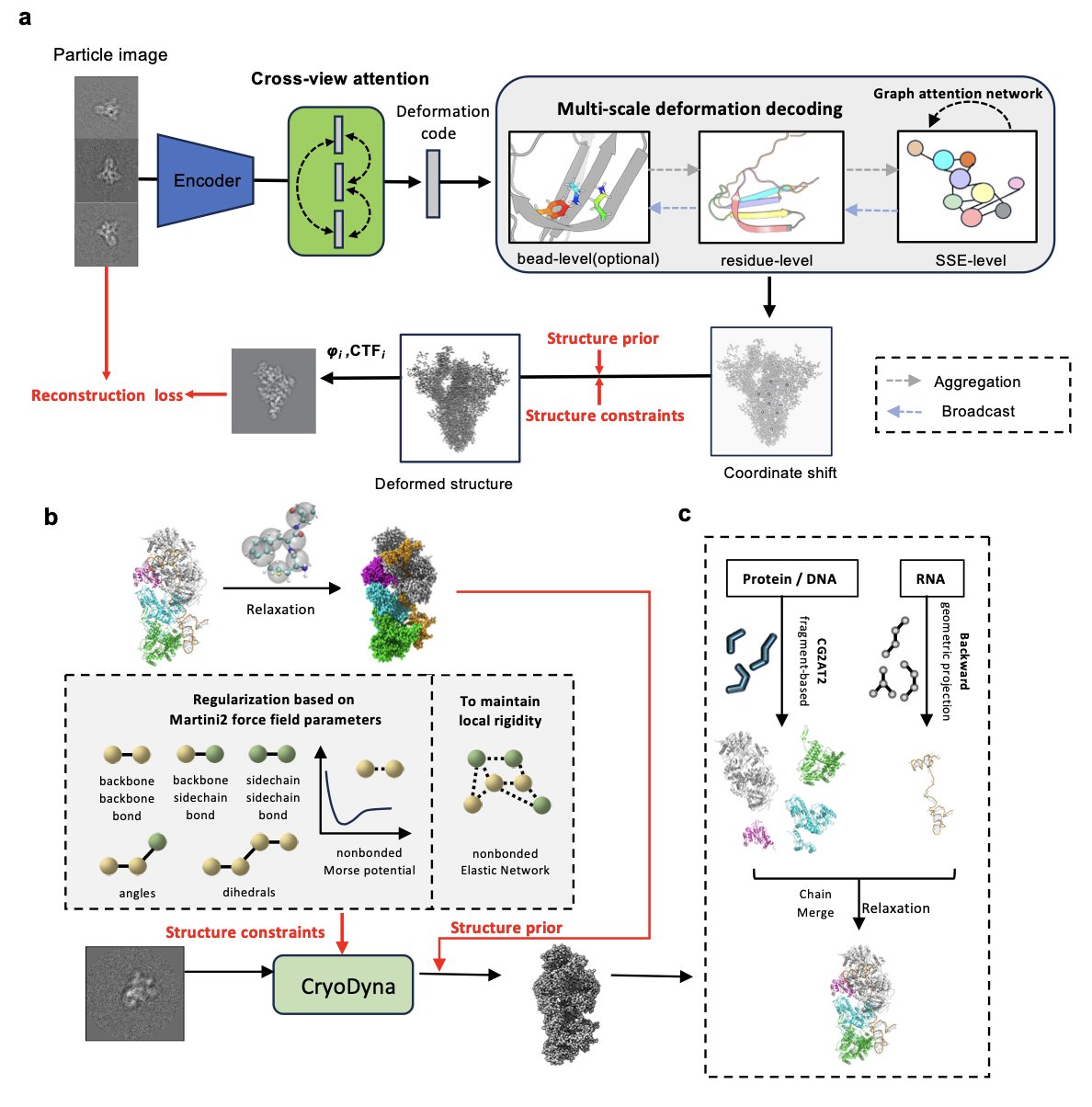

The traditional workflow requires classifying particles, reconstructing a few discrete static structures, and then trying to connect them. CryoDyna uses a more direct, end-to-end deep learning framework: you input tens of thousands of 2D particle images from different orientations, and it directly outputs a continuous dynamic model.

This process relies on two key technologies.

First is the cross-view attention module. To determine the 3D shape of an object, you need to look at it from different angles. This module can simultaneously analyze 2D projection images from different directions and fuse the information. This helps to cross-validate, reduce noise, and ensure the final reconstructed 3D dynamics are geometrically self-consistent.

Second is multi-scale deformation prediction. This method is like painting: you start by sketching the broad outline and movement (coarse-grained global motion) and then add the details (fine changes in local structures). CryoDyna first learns the large-scale movements of the protein and then gradually refines the local structures. This coarse-to-fine strategy allows it to accurately capture structural changes at multiple scales, from global to local.

It incorporates physical laws

To prevent the AI model from generating results that defy the laws of physics, CryoDyna incorporates a coarse-grained model based on MARTINI. As it learns the protein’s motion, it is constrained by physical rules, ensuring that the predicted conformational changes are energetically plausible. Then, through a “back-mapping” process, this physically consistent coarse-grained dynamic model is converted back into a detailed all-atom model. The resulting dynamic model not only has near-atomic resolution but is also physically meaningful.

What can it do?

The researchers validated CryoDyna’s capabilities on several complex systems. For example, they resolved the dynamics of a previously unseen region in the RAG signal-end complex and mapped the state changes of the ribosome during translocation. It can also reveal the coordinated movements between proteins and RNA.

In drug development, CryoDyna can show the opening and closing of a kinase activation loop or the details of how a GPCR is gradually activated by a ligand. We can also analyze how a drug molecule locks a target in an inactive conformation. This information is crucial for designing more effective and specific drugs.

CryoDyna fills the gap between static Cryo-EM analysis and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, allowing researchers to explore the dynamic processes of proteins more quickly and intuitively using experimental data.

📜Paper: CryoDyna: Multiscale end-to-end modeling of cryoEM macromolecule dynamics with physics-aware neural network 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.16510 💻Code: https://github.com/Qmi3/CryoDyna

4. Chemical Language Models: Diversity Beats Brute-Force Scaling

In the field of AI drug discovery, there’s a common belief that if you make the model bigger and feed it more data, magic will happen. This might be true for Large Language Models (LLMs) handling natural language, but it’s different for chemical language (SMILES). A new study on ChemRxiv systematically refutes this “brute-force” approach.

Scale isn’t a silver bullet

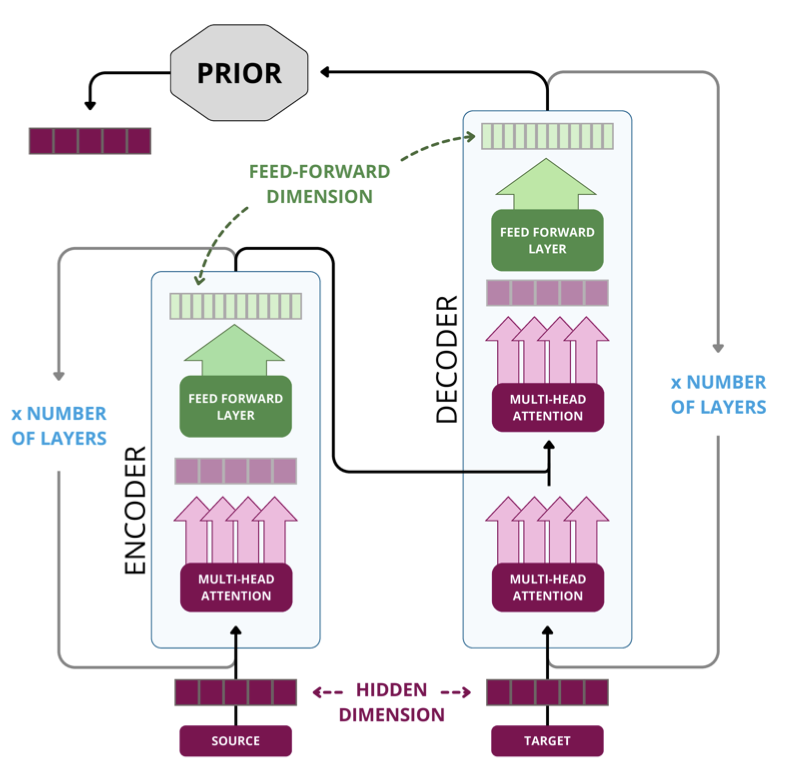

Researchers evaluated Transformer models based on an Encoder-Decoder architecture. After a certain point, increasing the model’s parameters did not significantly improve its ability to generate valid hit compounds. Simply increasing the amount of training data also showed diminishing returns beyond a specific point. This suggests that pharmaceutical companies don’t need to endlessly buy expensive computing power to train huge models; exploring chemical space has its own rules.

The “feeding” strategy

Since just “eating more” doesn’t work, the focus shifts to “eating a variety.” The researchers proposed a data diversification strategy: cluster molecules by molecular weight and then sample from each cluster.

The advantage of this approach is clear. If a model is trained only on a large number of similar benzene ring derivatives, the molecules it generates will tend to be very similar. By forcing the model to see molecules that are more widely distributed and structurally different across chemical space, the diversity of the generated “hit compounds” improves qualitatively. A core need in early drug discovery is to find potential molecules with different scaffolds.

Don’t trust the loss curve

The study points out that pre-training loss is not an accurate way to evaluate a model’s quality. In natural language processing, a lower loss usually means a better model. But in chemistry, a lower loss doesn’t correlate well with performance on downstream tasks like molecule generation or property optimization.

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) practitioners need to return to a more fundamental evaluation system. They should test models in realistic drug design scenarios, verifying whether the generated molecules comply with medicinal chemistry rules and are synthetically feasible and structurally novel.

This work points to a more cost-effective path for AI drug discovery: the priority should be on cleaning and curating high-quality, highly diverse chemical datasets. On the journey to find new drugs, broad exposure is more valuable than just rote memorization.

📜Title: Diversity Beats Size Scaling for Chemical Language Models 🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-k14gv

5. MolEdit: A New Way to Perform ‘Microsurgery’ on Molecular Models

AI models in science often face the problem of “knowledge ossification.” Once a model is trained, correcting errors or updating it with new experimental data is often very expensive. You either have to retrain it from scratch or risk “catastrophic forgetting” through fine-tuning—where fixing one bug breaks existing capabilities.

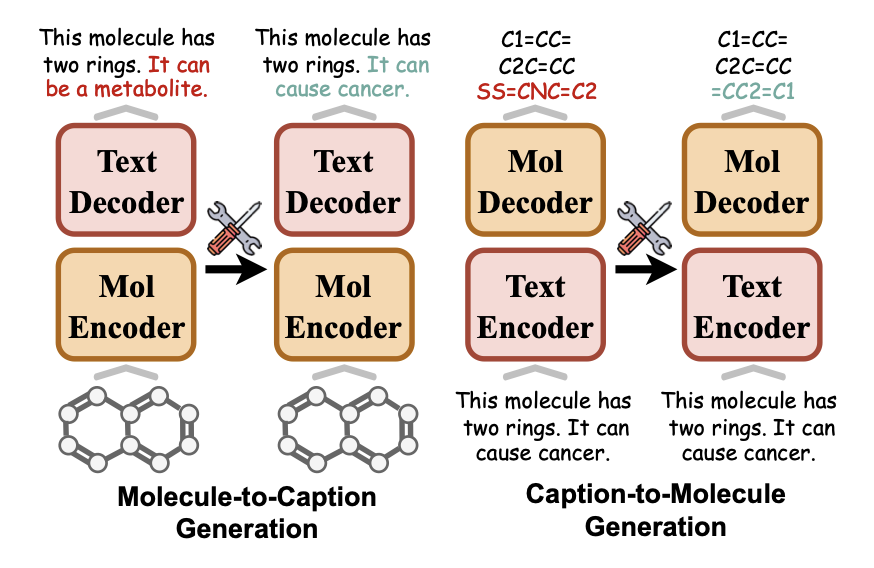

A new solution, MolEdit, has been developed for multimodal molecular language models (MoLMs). These models need to understand both chemical structures (like SMILES) and natural language descriptions, and the mapping between the two is complex. MolEdit acts like a precision surgical tool, allowing for targeted edits of specific molecular knowledge without damaging the model’s original abilities.

The system relies on two core designs.

First is MEKA (Multi-expert Knowledge Adapter). Molecular knowledge covers many dimensions, such as solubility, toxicity, and binding targets. MEKA works like a hospital’s triage desk, routing edit commands to the “expert module” responsible for the relevant area. This strategy allows for fine-grained control over multifaceted molecular knowledge.

Second is the EAES (Expert-aware Editing Switch). This adds a “safety lock” to the model. The edited knowledge is activated only when the user’s input closely matches a stored “patch.” If the query is unrelated, the system remains silent and uses its original knowledge base. This mechanism greatly reduces the interference of new knowledge on the model’s general capabilities.

To test its effectiveness, the researchers created the MEBench benchmark. Tests on two major multimodal molecular models, MoMu and MolFM, showed that MolEdit improved the accuracy of error correction (reliability) by 18.8% and the ability to protect unrelated knowledge from being corrupted (locality) by 12.0%.

This will give medicinal chemists and computational biologists a more controllable AI assistant. When they find that a model has an incorrect description of a lead compound or when new SAR (structure-activity relationship) data becomes available, they can directly “hot-update” the model using MolEdit. This helps build a scientific discovery engine with real-time, accurate data that can evolve over time.

📜Title: MolEdit: Knowledge Editing for Multimodal Molecule Language Models 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.12770v1 💻Code: https://github.com/LzyFischer/MolEdit