Table of Contents

- Giving general Large Language Models (LLMs) a specialized chemistry vocabulary helps them understand SMILES like text, improving drug synthesis design and property prediction.

- MIST sets new records in scale and performance. It uses a new molecular representation to understand the fundamental principles of chemistry, moving beyond simple pattern matching.

- By giving each atom in a molecule a unique number, a Large Language Model can think like a chemist about how to deconstruct it, with almost no need for specialized reaction data training.

- By combining Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network centrality with node embeddings, this research achieved a high accuracy of 0.930 and used GradientSHAP to show that “degree centrality” is the key metric for predicting gene essentiality.

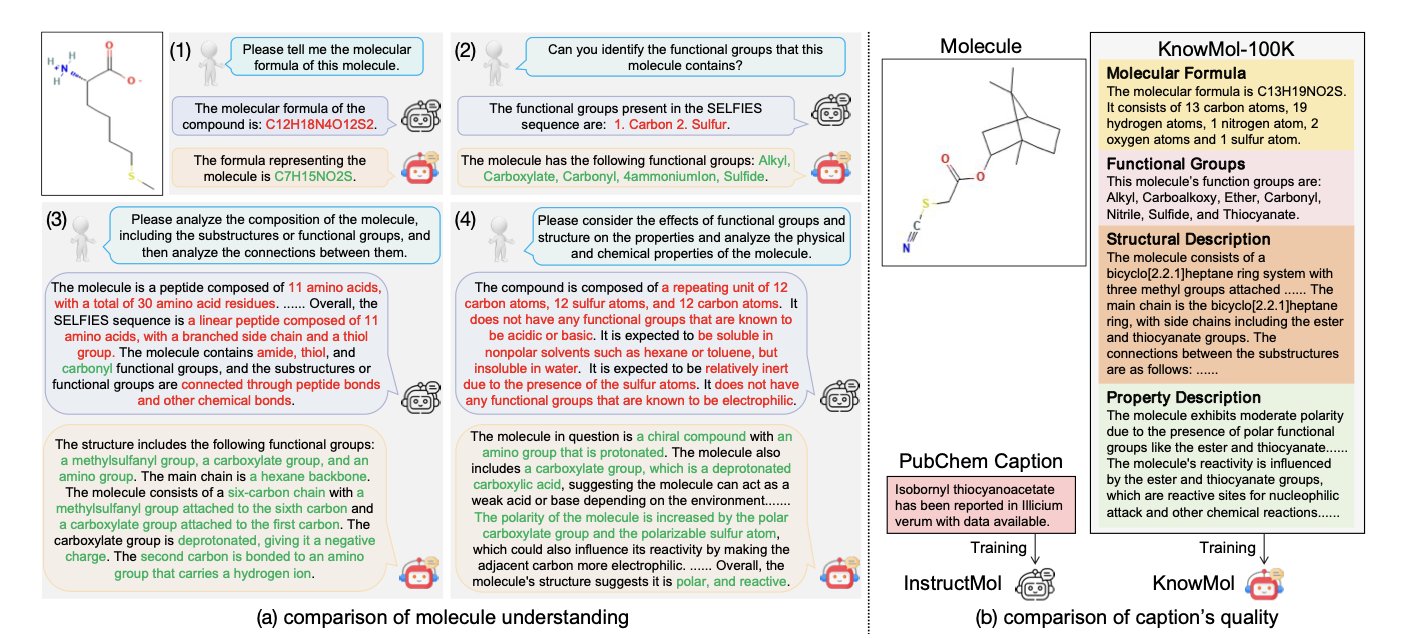

- KnowMol uses a carefully built set of chemical knowledge to teach a Large Language Model how a chemist thinks, enabling it to not just recognize molecules but understand the principles behind them.

1. Do LLMs Understand Chemistry? Extending Vocabulary to Break the SMILES Bottleneck

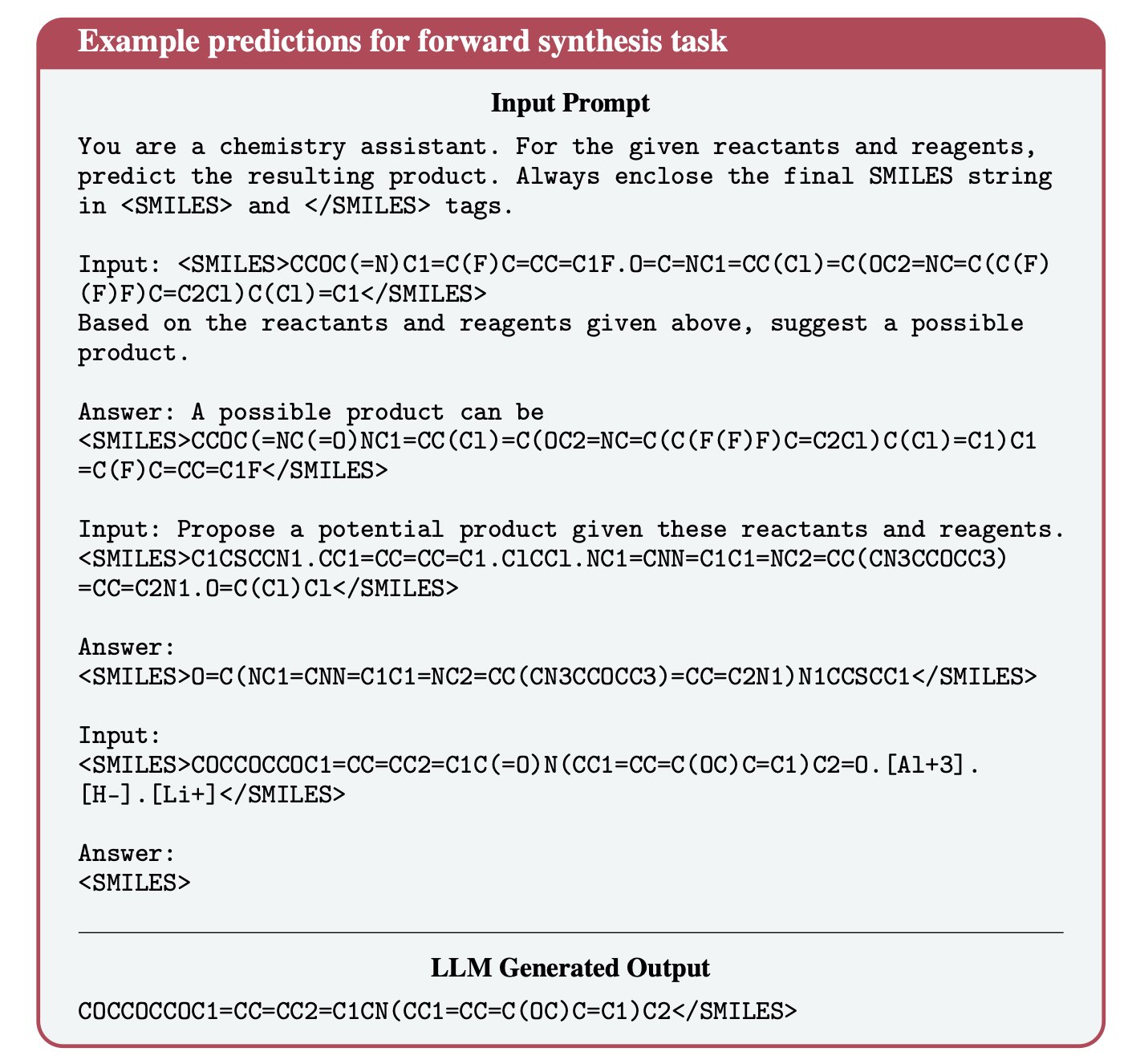

Large Language Models (LLMs) often struggle with chemistry. To a standard LLM, a molecule’s SMILES string looks like nonsense. A general-purpose tokenizer, trained on plain text, will mechanically chop up a chemical string like c1ccccc1 into meaningless character fragments. The model can then recognize the characters but not the chemical logic behind them. This is known as the “Tokenization Bottleneck.”

To fix this, the researchers rebuilt the model’s vocabulary instead of changing its architecture. They avoided complex dual-encoder setups or external graph neural networks and instead taught the model “chemistry words.” Through data-driven analysis, they extracted 17,795 new tokens from a massive corpus of SMILES strings.

Extending the vocabulary changes how the model sees a molecule. A benzene ring, once split into isolated characters, is now recognized as a complete substructure with chemical meaning. This approach significantly reduces information fragmentation.

To get the model to internalize these new words, the team performed continued pre-training. By mixing chemistry-specific text with general-purpose text, the model learned specialized chemical knowledge while retaining its original language capabilities, which helped avoid catastrophic forgetting.

Experiments showed that this “extended-vocabulary” model outperformed both the original base model and models that only underwent simple continued training. This was true across core tasks like retrosynthesis, forward synthesis prediction, molecule captioning, and property prediction.

This work shows that SMILES is, in essence, a language. Molecular structures don’t need to be treated as a special modality. As long as the vocabulary is adapted, an LLM can understand the word “benzene” and its chemical structure within the same semantic space. This helps lay the groundwork for building a unified, general-purpose foundation model for chemistry.

📜Title: The Tokenization Bottleneck: How Vocabulary Extension Improves Chemistry Representation Learning in Pretrained Language Models

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.14365v1

2. The MIST Chemistry Large Model: AI Starts to Understand Chemistry’s First Principles

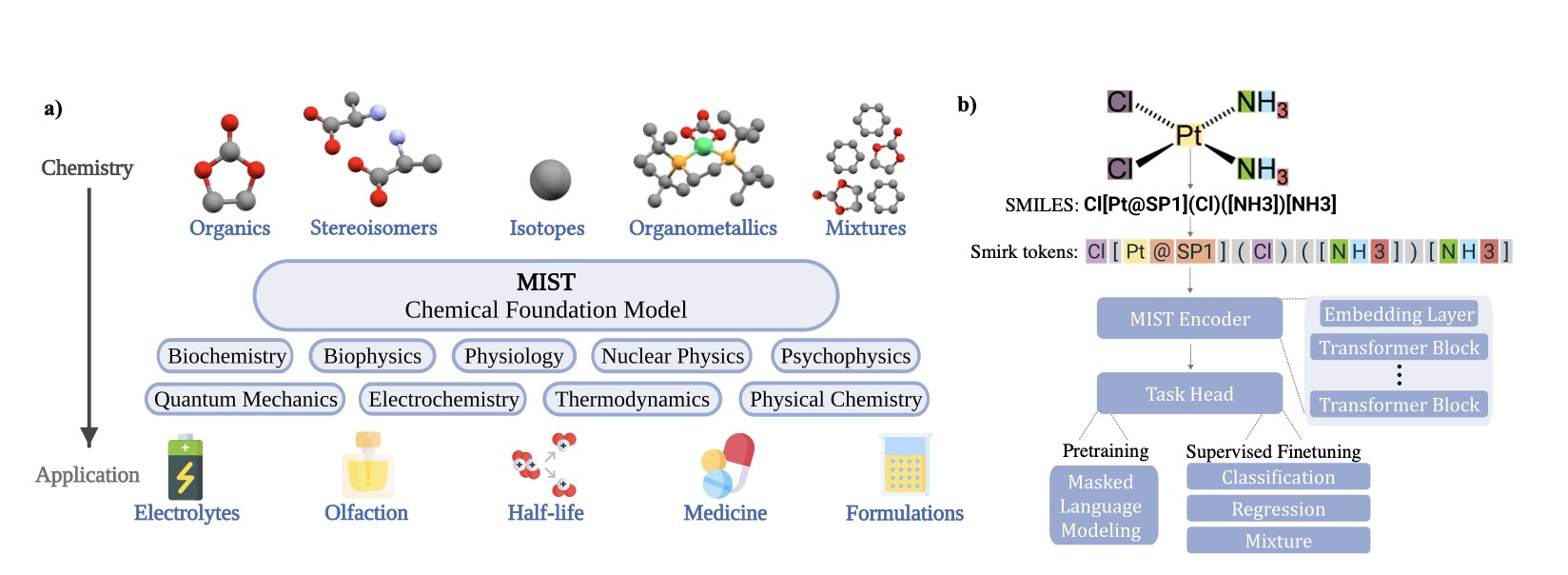

Past methods for teaching computers chemistry, like molecular fingerprints, SMILES strings, or graph representations, were all high-level abstractions of molecules. They lost a lot of information, like describing a person only by their ID number.

The researchers behind MIST broke molecules down into their most basic information: atomic nuclei (element type), electron clouds (key to chemical reactions), and 3D geometry (which determines how molecules interact). They packaged this information into a new “language” of tokens for the model to learn.

This approach is like teaching a child about the world. Instead of just showing a photo of an apple (2D structure), you let them touch its shape, feel its texture, and smell it (3D geometry and electronic information). Knowledge learned this way is deeper and more generalizable.

During training on massive datasets, the model independently “discovered” the patterns of the periodic table. By analyzing basic information like nuclei and electrons, it figured out trends on its own, such as “lithium and sodium have similar properties,” even though no one explicitly taught it that. MIST is learning to understand chemistry from underlying physical laws, moving beyond simple interpolation of input data. This is a key step from rote memorization to genuine understanding.

Understanding isn’t enough; the model also has to solve problems. MIST was applied to two real-world challenges: screening solvents for battery electrolytes and predicting the odor of molecules. Both tasks are complex. The first requires predicting multiple macroscopic physicochemical properties, while the second touches the intersection of biology and chemistry. MIST achieved state-of-the-art results on both. A good foundation model, like a chemist with a solid foundation, can be quickly fine-tuned to solve specific problems in different fields.

A major challenge in training large models is tuning hyperparameters, which consumes huge computational resources. This team proposed “hyperparameter-penalized Bayesian neural scaling laws,” an efficient model training method that can reduce computational costs by an order of magnitude. This is good news for academic labs or startups with limited resources.

They have released all their code, model weights, and training methods. Anyone can build on their work to explore unknown areas of chemical space. This is how you push an entire field forward.

Work like MIST points to a future for AI for Science where AI transforms from a computational tool into a research partner, discovering new scientific principles from the vast amounts of data we overlook.

📜Title: Foundation Models for Discovery and Exploration in Chemical Space

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.18900

3. A New Way to Use Large Models: Atom-Level Reasoning for Retrosynthesis

In synthetic chemistry, planning a retrosynthesis route is like disassembling a precision watch without a blueprint. It requires experience and intuition to know where to start. Traditional computational methods rely on huge, annotated databases of chemical reactions, which is like making a model “memorize recipes.” The problem is that if the model encounters a new molecule or reaction, it fails because it has no precedent.

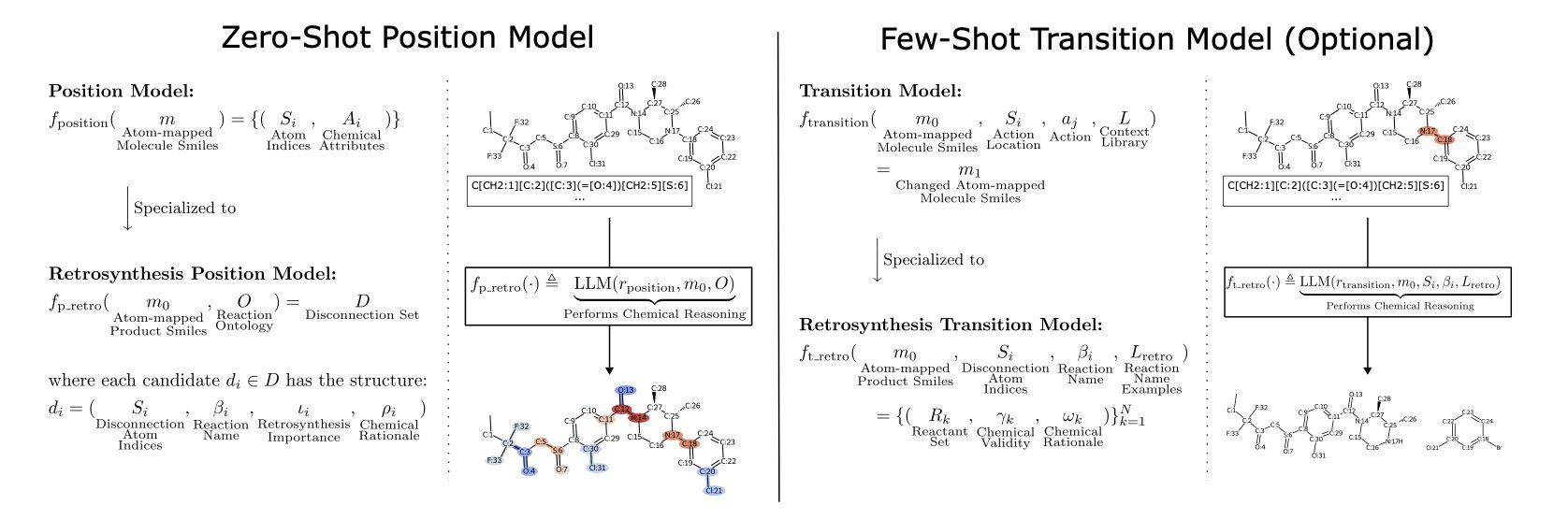

Researchers have proposed a new method to teach a Large Language Model (LLM) to analyze molecular structures through reasoning, just like a chemist.

The core of this method is “Atom-Anchoring.”

Molecules are often represented by SMILES strings. For example, isopropanol is CC(C)O. In this format, it’s hard for a computer to tell the different carbon atoms apart. The researchers introduced a simple change: give every atom a unique number, like C1C2(C3)O4.

This change makes a fundamental difference.

It’s like telling a robot to assemble LEGOs. The instructions change from a vague “connect the red block and the blue block” to a precise “connect red block #A73 to blue block #B12.” With atom numbers, the LLM has a tool to accurately refer to any part of the molecule. It can focus on the fundamental level of atoms and bonds instead of looking at a fuzzy overall structure.

Based on this tool, they designed a two-step process that mimics a chemist’s thought process.

Step 1: Find the Break Point (Position Model)

The researchers gave a molecule with numbered atoms to an LLM (like GPT-4) and asked a zero-shot question: “Looking at this molecule, which chemical bond is the best one to break for retrosynthesis? What type of reaction might this be?”

Zero-shot means they provided no examples, relying entirely on the chemical knowledge the model learned from massive amounts of text. It’s like consulting a chemistry student who can make judgments based on first principles.

The results showed that the model has strong “chemical intuition.” Its success rate in identifying reasonable break points was over 90%, showing that it could already spot the “weak links” in a molecule.

Step 2: Predict the Reactants (Transition Model)

Once the model identified a break point (e.g., cutting the bond between C5 and N2) and a possible reaction type (e.g., amide bond formation), it moved to the second step.

Here, the researchers provided a few simple examples—a few-shot prompt—like a teacher highlighting key topics before an exam. Then they asked: “If you cut between C5 and N2 for an amidation reaction, what are the starting materials?”

The model used this information to output the corresponding reactant molecules. For a model with almost no training on specific chemical reaction data, a final success rate of over 74% is a significant achievement.

This work shows a new way to work with large language models, turning them from a database for search and matching into a “chemistry assistant” with reasoning abilities.

The atom-anchoring method allows LLMs to be useful for chemistry problems where data is scarce, like predicting molecular properties or designing new catalysts. It provides a general blueprint for mapping abstract chemical knowledge onto specific molecular structures. The model’s success rate for correctly naming the reaction type was 40%, indicating its “knowledge base” still has gaps. But it has learned the right “thinking method,” which is a critical step.

📜Title: Atom-Anchored LLMs Speak Chemistry: A Retrosynthesis Demonstration

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.16590v1

4. AI and PPI Networks Predict Cancer Targets

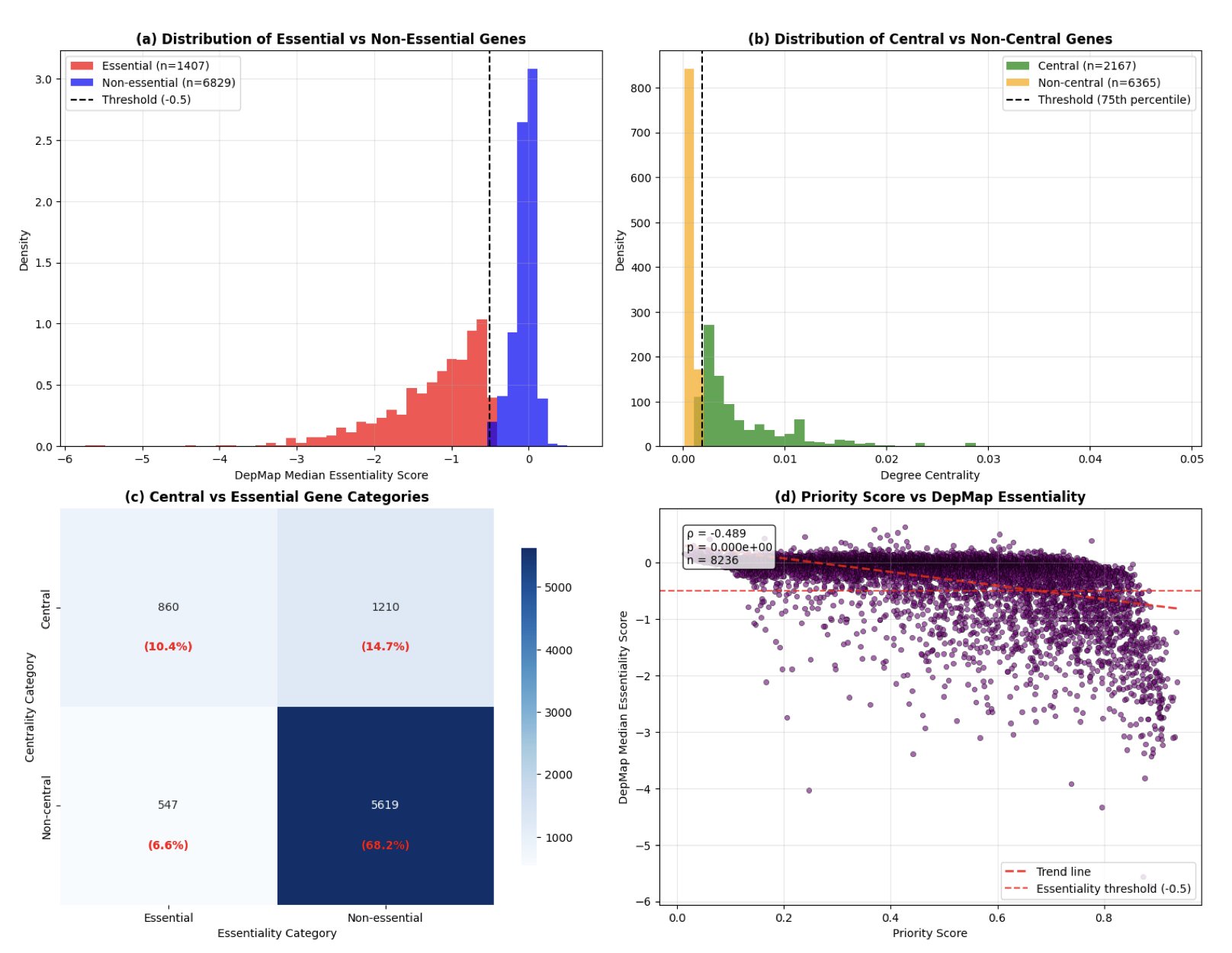

In drug development, target selection is the most expensive and failure-prone stage. AI can help with screening, but it often suffers from the “black box” problem: the machine gives a recommendation but can’t explain why. For a project that costs a huge amount of money and time, a cold probability score is not nearly enough. A new study on ArXiv aims to solve this problem.

Looking at “relationships,” not just “who”

Instead of just piling on omics data, this study uses the high-quality Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network from the STRING database. It combines traditional network centrality measures (which gauge a protein’s importance as a hub) with Node2Vec embeddings. This is like studying both the protein itself and its “status” and “social circle” within the network. The results showed the model achieved an AUROC of 0.930, which is state-of-the-art in computational oncology.

SHAP values reveal the truth

The core highlight of the paper is its use of GradientSHAP analysis to reverse-engineer the model’s decisions. The data showed that “degree centrality” is highly correlated with a gene’s importance (correlation of -0.357). The biological explanation is simple: the more connections a protein has, the more likely it is to be essential for a cancer cell’s survival. The data provided hard evidence for this biological intuition.

A better way to rank

The study proposes a “Blended Scoring” mechanism, which combines the model’s predicted probability with the magnitude of its SHAP attribution. This screening method is like an audition where judges consider both the high score and whether the reasons for that score are solid. The resulting list of targets has both statistical confidence and a clear mechanistic explanation.

Putting it to the test

In the validation phase, the model accurately identified ribosomal proteins (like RPS27A, RPS17) and the well-known oncogene MYC. The fact that these widely recognized “essential genes” were successfully captured proves that the model has grasped the underlying logic of cancer biology.

This kind of transparent, explainable in silico design could gradually reduce our reliance on animal models. For drug development, knowing why a target was chosen is more valuable than just getting a high score.

📜Title: Explainable deep learning framework for cancer therapeutic target prioritization leveraging PPI centrality and node embeddings

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.12463

5. KnowMol: Giving Molecular Large Models a Chemistry Lesson

In drug discovery, we’ve been looking for an AI that can “understand” chemistry. Some past Molecular Large Language Models (Mol-LLMs) are good at finding patterns, like a student who gets high scores by cramming for tests. If you give them a SMILES string, they can predict properties or even generate new molecules, but they can’t explain the reasons behind the chemical structure. They recognize patterns, but they don’t understand the chemical principles.

The work behind KnowMol is about giving this specialized student the critical chemistry lesson it’s missing.

The Core Idea: Feed it knowledge, not just data

Many AI models are trained on huge amounts of data. But chemistry is a science with its own internal logic and hierarchical structure. A molecule has functional groups, scaffolds, and pharmacophores—concepts that chemists have developed over hundreds of years.

The KnowMol researchers first systematically organized this chemical knowledge into a high-quality dataset called KnowMol-100K. This dataset contains detailed annotations for 100,000 molecules, covering multiple levels from atoms and functional groups to overall molecular properties. This is like giving the AI a chemistry textbook with detailed notes, rather than letting it wander through a massive library of scientific papers on its own. By learning these annotations, the model can connect text descriptions to specific chemical structures.

Talking to the AI in a chemist’s language

To help the model understand molecules better, the first step was to fix the way they are represented.

The commonly used SMILES strings are concise but “brittle” for a machine. A tiny change can produce an invalid or completely unrelated molecule, causing the model to generate a lot of meaningless “gibberish.”

KnowMol uses a more robust language called SELFIES. SELFIES is designed to ensure that almost any string corresponds to a valid chemical structure. This is like installing a grammar checker for the model, making sure every molecule it generates follows the basic rules of chemistry and improving the efficiency and success rate of generation tasks.

Besides optimizing the 1D string representation, the researchers also improved the model’s understanding of 2D graphs by designing a hierarchical graph encoder. A normal encoder sees a molecule as a flat graph of atoms and bonds. But this hierarchical encoder can think like a chemist, identifying the “neighborhoods” (functional groups) and “main roads” (molecular scaffold) in the graph and understanding their relationships. This part-to-whole way of understanding is closer to how human chemists think.

How well does it actually work?

The experimental results show that this approach works well. Whether for molecule captioning tasks or generating molecules from a description, KnowMol outperformed previous models.

For example, in question-answering tasks, it can more accurately identify molecular formulas, functional groups, and analyze structure and properties. It hasn’t just memorized knowledge; it has learned to apply it. For drug discovery, researchers can make more specific requests, like “I want a small molecule that can bind to the hinge region of a specific kinase and also has good solubility,” and the model is more likely to give a reasonable answer.

KnowMol’s work suggests that in the field of AI for drug discovery, simply chasing bigger models and more data may not be the best solution. Figuring out how to efficiently “teach” AI the valuable knowledge that human chemists have accumulated—turning it from a pattern-recognition tool into a partner that truly understands chemistry—may be a more important direction for the future.

📜Title: KnowMol: Advancing Molecular Large Language Models with Multi-Level Chemical Knowledge

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.19484