Table of Contents

- Researchers developed a quantum mechanics-based hydropathic scoring function. By accurately modeling water’s role and including ligand conformational energy, it raises the accuracy of predicting drug binding poses to around 90%.

- PUMBA uses the Mamba architecture to evaluate protein docking models more accurately and transparently, improving on existing methods.

- MultimerMapper solves a major challenge in AI protein structure prediction. It infers the precise composition of a complex by analyzing its dynamic assembly process.

- The CDI-DTI framework tackles the problem of predicting interactions for new drugs or targets by fusing multiple data types and ensuring interpretability, bringing computational predictions closer to real-world R&D.

- The DyCC framework improves the performance and generalization of molecular graph autoencoders by dynamically adjusting its masking strategy and incorporating chemical prior knowledge.

1. Using Quantum Mechanics to Account for Water in Drug Docking

Computational drug design has a long-standing problem: molecular docking software can generate thousands of plausible binding poses for a ligand, but which one is right? The answer depends on the “scoring function.” Many of these functions handle the role of water too crudely, often misleading us with high-scoring but incorrect poses.

Traditional scoring functions, like the classic HINT, rely on empirical atomic parameters to estimate hydrophobic interactions. That’s like using a fixed ruler to measure objects of all different shapes. It’s fast, but its precision is limited because it can’t capture the subtle effects of how an atom’s electron cloud changes in a specific chemical environment.

This work takes a different approach, using Quantum Mechanics (QM) to solve the problem.

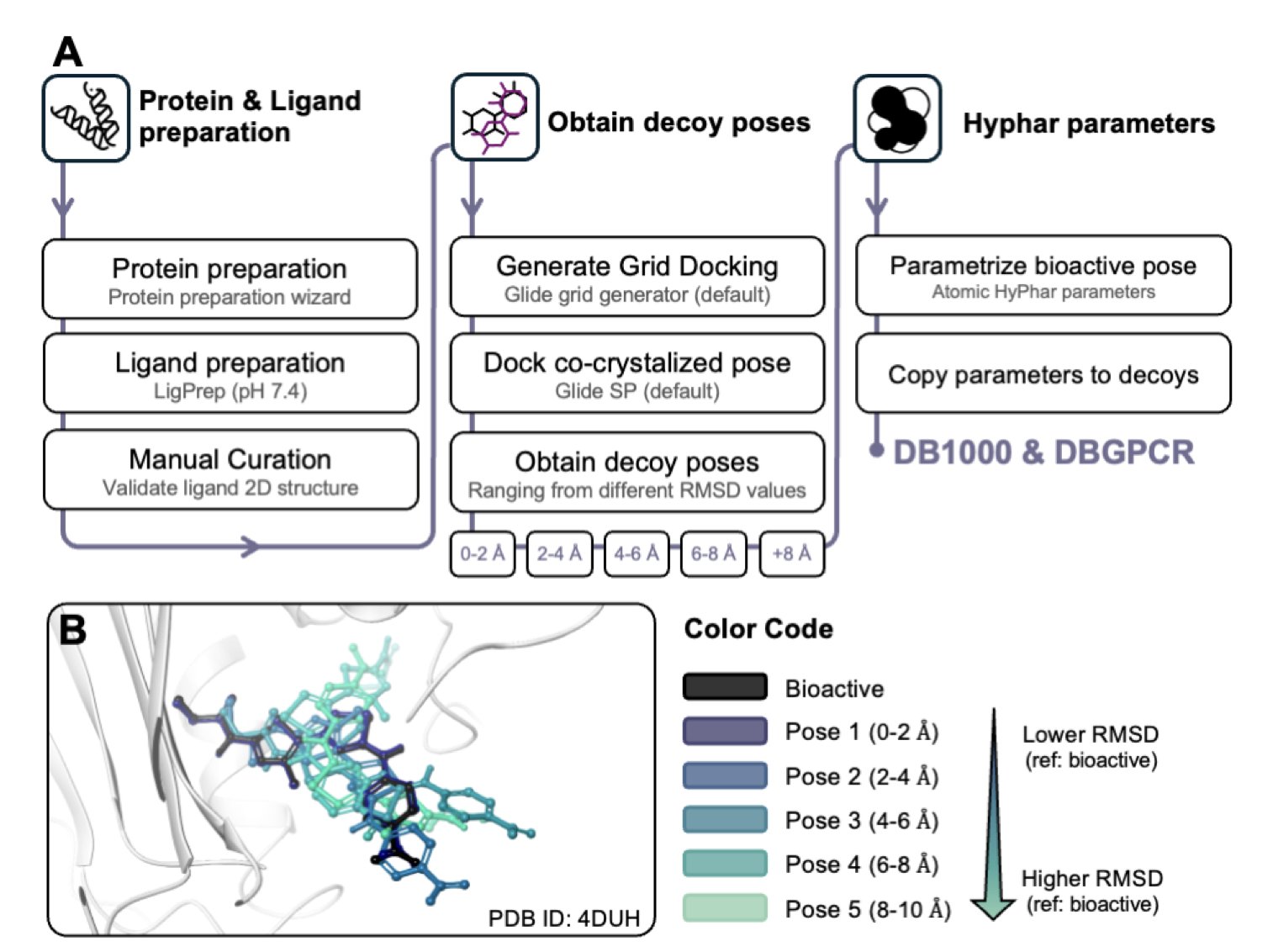

How it works

Instead of using preset empirical parameters, the researchers perform QM calculations for each atom to get a more fundamental physical quantity: solvation free energy. This value accurately reflects the energy gained or lost when moving an atom from water into a protein’s binding pocket. Based on these QM-derived atomic descriptors, they built a new hydropathic scoring function. The function’s main job is to evaluate “hydropathic complementarity”: do the hydrophobic parts of the ligand line up with the hydrophobic parts of the pocket, and the same for hydrophilic parts?

A key addition

A highlight of this method is its integration of the ligand’s “conformational strain energy.” A small drug molecule is like a flexible gymnast. To find the best spot in the protein pocket, it might have to twist itself into a high-energy pose. Even if this pose gets a high score for its hydrophobic match with the pocket, the energy cost of holding that pose makes it unstable.

Many scoring functions ignore this. The new method adds a penalty term that filters out these overly “strained” poses. Adding this term pushed the prediction accuracy up to about 90%. This shows that a good bond depends not just on the “external” fit between the ligand and the protein, but also on the ligand’s own “internal” comfort.

Data validation

To test their method, the researchers used a large benchmark dataset (DB1000) containing 1,000 protein-ligand complexes. Their results were better than traditional empirical methods.

They also ran a validation test on an external dataset of G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). GPCRs are an important and structurally complex class of drug targets with diverse binding pockets. In this difficult test, the new method still achieved an 80.3% accuracy rate, showing it is broadly applicable and not just tuned for specific types of targets.

An interesting finding

The study also found that the scoring function performs better in pockets with more polar groups, which makes chemical sense. The pocket needs some hydrogen bond donors or acceptors to act as “anchors” that roughly fix the ligand in place. Then, hydrophobic forces can fine-tune the fit. If the pocket is just a pure hydrophobic “oil slick,” the ligand has too many ways to float around, making it hard to lock down the single correct pose.

This work provides a scoring tool that is closer to physical reality. It reminds us that in drug design, the role of water is far more complex and important than we might think. Using a fundamental physical principle like QM to guide drug discovery is helping move the field from empirical tinkering toward precise design.

📜Title: Assessing the ligand native-like pose using a quantum mechanical-derived hydropathic score for protein-ligand complementarity 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.20.683430v1

2. Mamba Architecture Improves Protein Docking Evaluation with PUMBA

Computer-aided drug discovery faces a classic challenge: protein-protein docking. A computer can generate thousands of possible ways for proteins to fit together, known as “decoys.” But the hard part is identifying the single, correct native conformation from this vast pool. This task falls to a docking scoring function.

Past scoring tools have varied, and in recent years, models based on the Transformer architecture have appeared. But when Transformer models process protein sequences, they analyze all amino acid residues at once. This leads to high computational costs and is not very efficient at capturing long-range interactions.

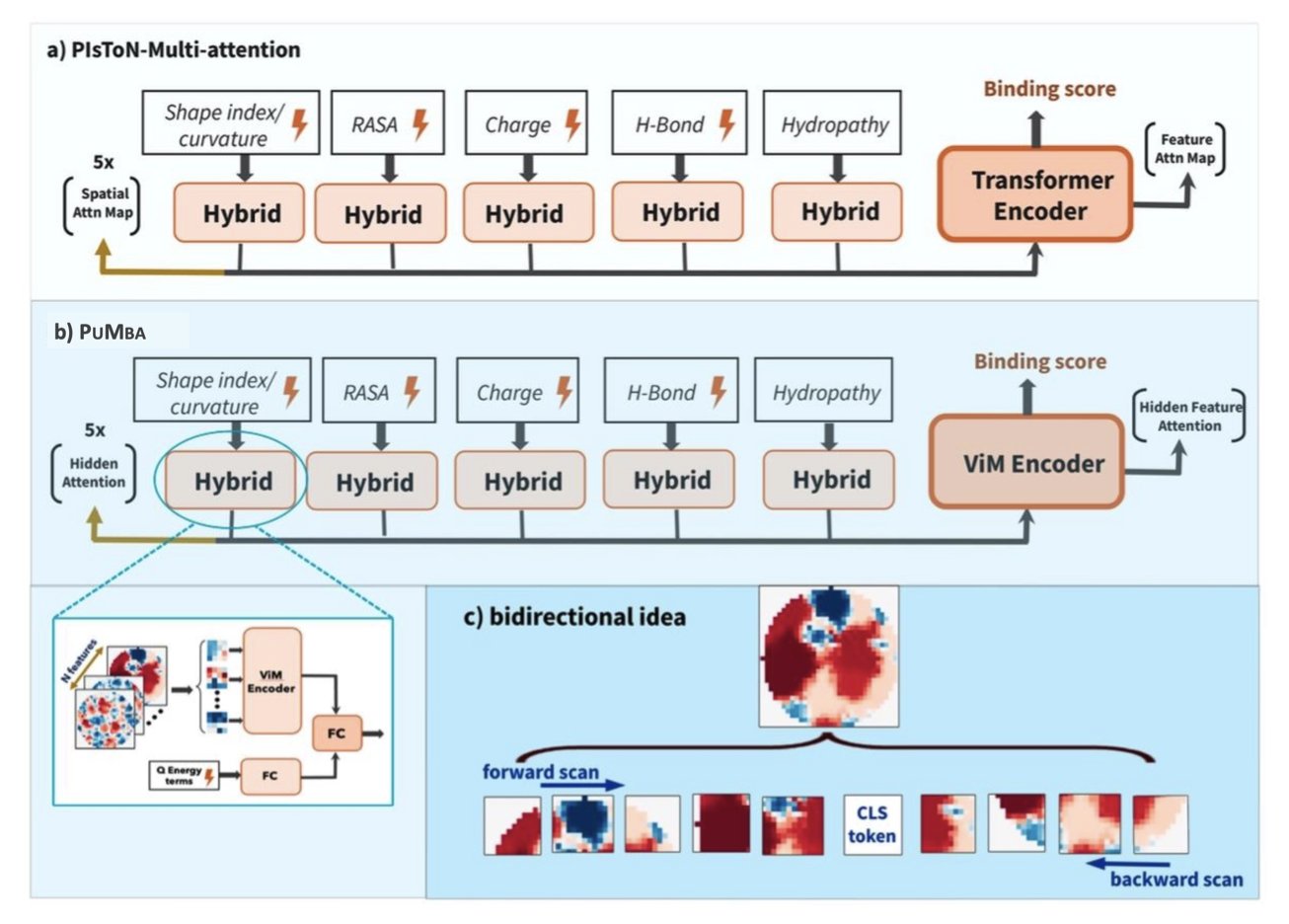

The PUMBA model uses the Mamba architecture to address this issue.

Mamba works differently than a Transformer. It scans a sequence in order, like a person reading, carrying context along with it. This state-space mechanism makes it more efficient at capturing long-range dependencies and lowers computational costs.

PUMBA applies the Mamba architecture to evaluate protein docking interfaces. It converts the interaction interface of a protein complex into image-like data for analysis. Using Mamba’s strengths, PUMBA can simultaneously capture local chemical interactions, like hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic effects, and the overall shape complementarity of the interface.

On several public benchmark datasets, PUMBA consistently outperformed the previous model, PIsToN, with a particularly strong advantage on some notoriously difficult datasets. This suggests the model has learned more generalizable principles of protein interaction chemistry and physics.

A key feature of PUMBA is its interpretability. Unlike black-box models, PUMBA can use mathematical reconstruction to generate an “implicit attention matrix.” This matrix reveals the basis for the model’s decisions, showing which amino acid residue interactions were critical to its score.

This interpretability has direct value for drug development. For example, when developing a drug to disrupt a specific protein interaction, PUMBA can not only evaluate the docking results but also highlight the key regions of the interaction interface. This provides a clear target for drug design, turning the model from a simple scoring tool into an analytical tool that offers insights.

PUMBA’s success demonstrates the potential of new architectures like Mamba in bioinformatics. It offers an effective new approach, beyond Transformers, for solving problems related to sequences and structures.

📜Paper: Evaluating protein binding interfaces with PUMBA 🌐Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.16674

3. AI Protein Complex Prediction: From Still Snapshots to a Dynamic Movie

The arrival of tools like AlphaFold changed how we predict the structure of a single protein. It was like getting a camera that could take high-resolution photos of molecules. But in biology, function is often carried out by protein complexes, which constantly assemble and disassemble inside the cell, like a crowded dance.

Tools like AlphaFold-Multimer can predict the structure of these complexes, but they require the user to specify the “recipe” of the complex beforehand—its stoichiometry. For example, you have to input “two A proteins and one B protein” to predict an A₂B₁ complex. In the real world, we often don’t know this exact recipe.

What’s more complicated is that protein behavior is “context-dependent.” The conformation of protein A when bound to protein B might change after protein C joins the group. It’s like how a person’s posture and role are different in a one-on-one conversation versus a three-person discussion. Existing tools struggle to capture these dynamic changes.

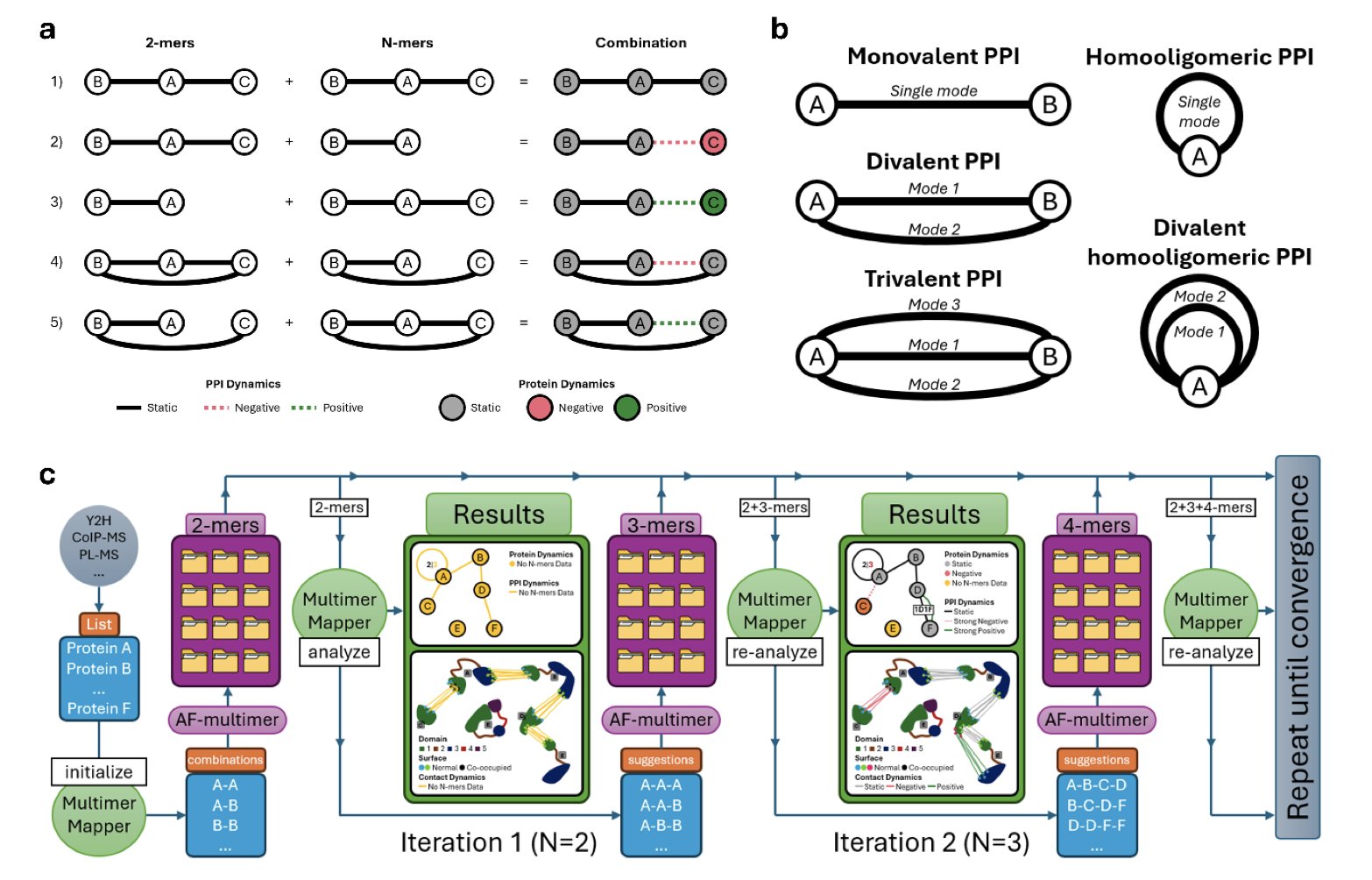

How MultimerMapper works

MultimerMapper is designed to solve these problems of “recipe” and “context.” It acts like a detective, piecing together the full picture by analyzing a large number of potential complex structures predicted by AI.

Here’s its workflow: 1. Systematic testing: It doesn’t assume a recipe. Instead, it tests all plausible combinations, like A+B, A+C, A+A+B, and A+B+C, generating an ensemble of structures that covers many possibilities. 2. Pattern analysis: It uses graph theory and statistics to analyze this ensemble. If the interface between A and B shows up consistently across all predictions, it’s marked as a core, static interaction. If it only appears when protein C is present, it’s a context-dependent, dynamic interaction. 3. Inference and visualization: By analyzing these interaction patterns, MultimerMapper infers the most likely composition and stoichiometry of the complex. It then visualizes this, clearly showing the core subassembly and any peripheral or transient members.

Application in drug development

If you want to develop a drug that disrupts the interaction between protein A and protein B, you need to know the actual conditions under which this binding occurs inside a cell. If the interaction requires the presence of protein C, then targeting the A-B interface alone might not work. The dynamic view provided by MultimerMapper helps researchers identify the biologically meaningful forms of a complex that are suitable drug targets.

The researchers used MultimerMapper to analyze a nuclear complex in trypanosomatids, a system known for being highly dynamic and complex, with unknown components and stoichiometry. The results proved that the tool can handle such complex problems.

This tool adds a layer of analysis and reasoning on top of prediction engines like AlphaFold. It helps us move from observing static structural snapshots to understanding the “movie” of how protein complexes dynamically assemble and function.

📜Title: Context-Dependent Protein Structure Prediction Analysis and Stoichiometry Inference with MultimerMapper 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.24.684463v1 💻Code: https://github.com/elviorodriguez/MultimerMapper

4. New AI Framework CDI-DTI Solves Drug Discovery’s “Cold-Start” Problem

In drug discovery, when faced with a brand-new target or a structurally novel molecule, older computational models often fail. This inability to handle new data is known as the “cold-start” problem, and it has been a roadblock for computer-aided drug design.

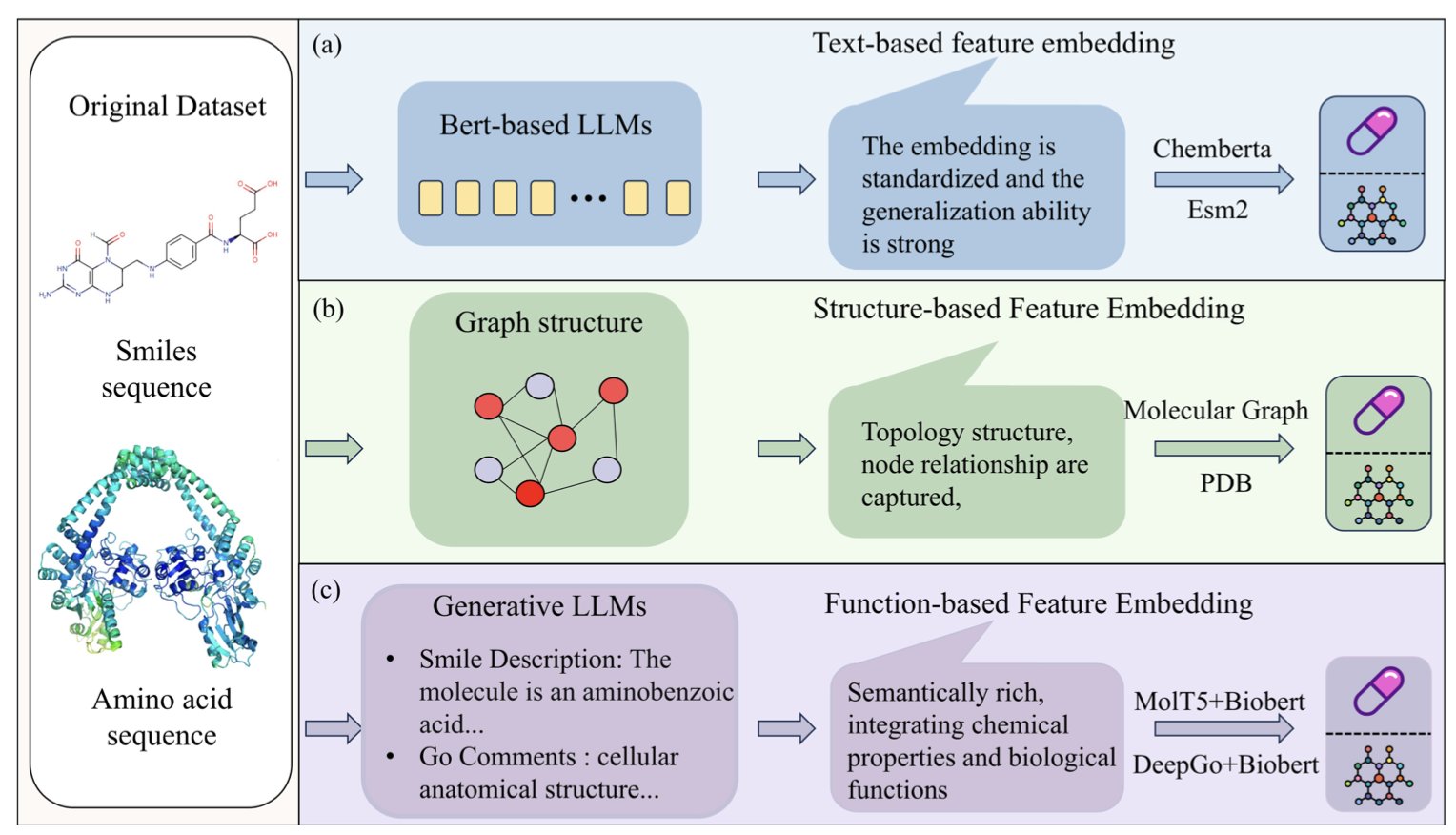

The CDI-DTI framework offers a solution.

The model works like a detective solving a case by integrating information from multiple sources. Specifically, CDI-DTI combines three key types of information about drugs and targets: 1. Structural information: The 2D/3D structure of the molecule and the primary sequence of the protein—the basic chemical and biological blueprints. 2. Functional information: Annotations about the protein’s function, such as the biological pathways it’s involved in. 3. Textual information: Relevant descriptions extracted from a vast body of scientific literature.

The key to the model’s success is its ability to fuse these different types of information (multi-modal features). The researchers used a two-step fusion strategy.

The first step is “early fusion.” The model uses a multi-source cross-attention mechanism to let the different types of information correlate with one another. This is like getting chemists, biologists, and clinicians together at the start of a project to ensure everyone has a comprehensive, unified understanding of the target.

The second step is “late fusion.” After building this high-level understanding, the model uses a bidirectional cross-attention layer to capture more detailed interactions. This is like moving to the specific molecular design phase, where you need to pinpoint which chemical group on the drug molecule interacts with which amino acid residue on the target protein.

Beyond predictive accuracy, drug development is concerned with “why.” A “black-box” model that can’t explain its reasoning has limited practical value. CDI-DTI was designed with interpretability in mind. It uses Gram Loss to align different features and a deep orthogonal fusion module to remove redundant information, making the model’s decision-making process clearer.

To verify that the model understood the interaction mechanisms, the researchers tested it on two classic examples: the EGFR kinase with Gefitinib and the BACE1 protein with Verubecestat. The model’s visualization analysis correctly highlighted the amino acid residues that experiments have already confirmed are critical for binding.

The ability to corroborate its findings with wet lab results is fundamental for building trust in a computational model. It shows that CDI-DTI has learned underlying biophysical and chemical principles, going beyond simply finding statistical patterns in the data.

📜Title: CDI-DTI: A Strong Cross-domain Interpretable Drug-Target Interaction Prediction Framework Based on Multi-Strategy Fusion 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.19520v1

5. DyCC: Making Molecular Graph Autoencoders Better at Chemistry

In molecular representation learning, Graph Autoencoders are a common technique, but traditional methods have limitations. The standard approach is to randomly mask part of a molecular graph and have the model predict the missing part. But using a fixed masking ratio for all molecules—whether simple or complex—is a “one-size-fits-all” approach that isn’t ideal.

Also, not all atoms in a molecule are equally important. A carbon atom in a benzene ring, for instance, has a different impact on a molecule’s properties than a carbon atom at the end of a side chain. Traditional random masking ignores this. At the same time, asking the model to predict the exact masked atom can be too strict a task. In chemistry, atoms with similar properties can sometimes be swapped with little effect on the molecule’s overall function, but a model would be penalized for not providing the one “correct” answer.

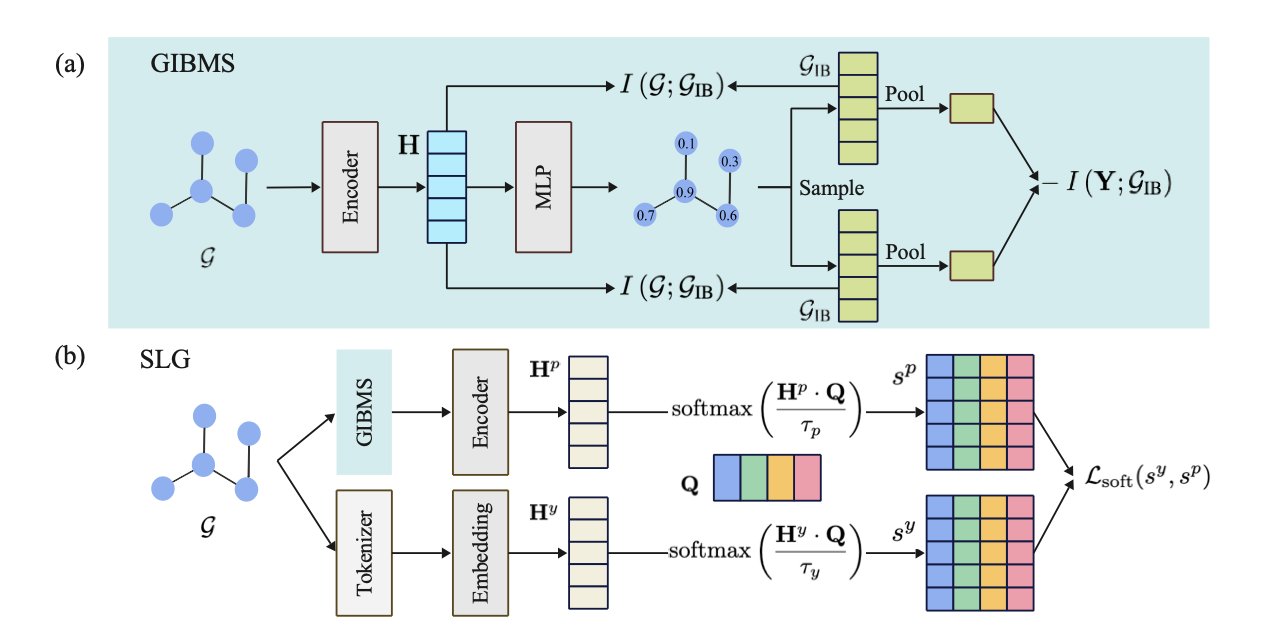

The Dynamic and Chemical Constraints (DyCC) framework described in this paper aims to solve these problems. Its core components are two modules: GIBMS and SLG.

GIBMS (Graph Information Bottleneck-based Masking Strategy) brings intelligence to the masking process. It uses Graph Information Bottleneck (GIB) theory to analyze a molecule and identify the core substructures that determine its properties. During masking, GIBMS preserves these key parts while prioritizing the masking of less important atoms. This forces the model to focus on learning important chemical patterns during reconstruction. The masking ratio and content change dynamically for each molecule, making the process smarter.

The SLG (Soft Label Generator) module optimizes the reconstruction target. Traditional methods require the model to make a black-or-white prediction, such as correctly identifying a masked atom as carbon. SLG turns this “hard label” into a “soft label.” Using a set of learnable prototypes, it defines the reconstruction target as a probability distribution over different atoms—for example, “a high probability of being carbon, a low probability of being nitrogen.” This approach is closer to chemical reality, where atom substitutions follow certain rules. It not only makes the learning task easier for the model but also makes the self-supervised signal more reasonable.

The DyCC framework combines GIBMS and SLG. It is also model-agnostic, meaning it can be used as a plug-and-play module with most major molecular graph autoencoder models. Experiments showed that models integrated with DyCC achieved better performance on multiple molecular property prediction tasks, setting a new state-of-the-art. This demonstrates that introducing dynamic adjustments and chemical knowledge during the pre-training phase can effectively improve a model’s performance.

📜Title: Dynamic and Chemical Constraints to Enhance the Molecular Masked Graph Autoencoders 🌐Paper: https://openreview.net/pdf/f6bfb8aa8ea6896b6d4ebfccada7e051c176fa2c.pdf