Table of Contents

- This study improves template-free retrosynthesis by teaching a model to “copy and paste” the unchanged parts of a molecule, making AI think more like a chemist.

- A fully automated cryo-EM workflow developed by the CryoSPARC team can solve complex protein structures without human intervention, promising to reshape the efficiency of drug discovery.

- Generative AI is accelerating bioscience, but it also brings the risk of designing harmful biological agents. We must build an adaptive biosecurity framework that can evolve with the technology.

- ProtoMol creates a unified “prototype” semantic space to align different information types—molecular structure diagrams and text descriptions—improving the accuracy and interpretability of molecular property prediction.

- This multi-scale machine learning model accurately predicts antibiotic resistance in ESKAPE pathogens and uncovers new resistance mechanisms, offering new tools for clinical diagnostics and drug development.

1. A New Approach to Retrosynthesis: Copy and Paste to Make AI Understand Chemistry

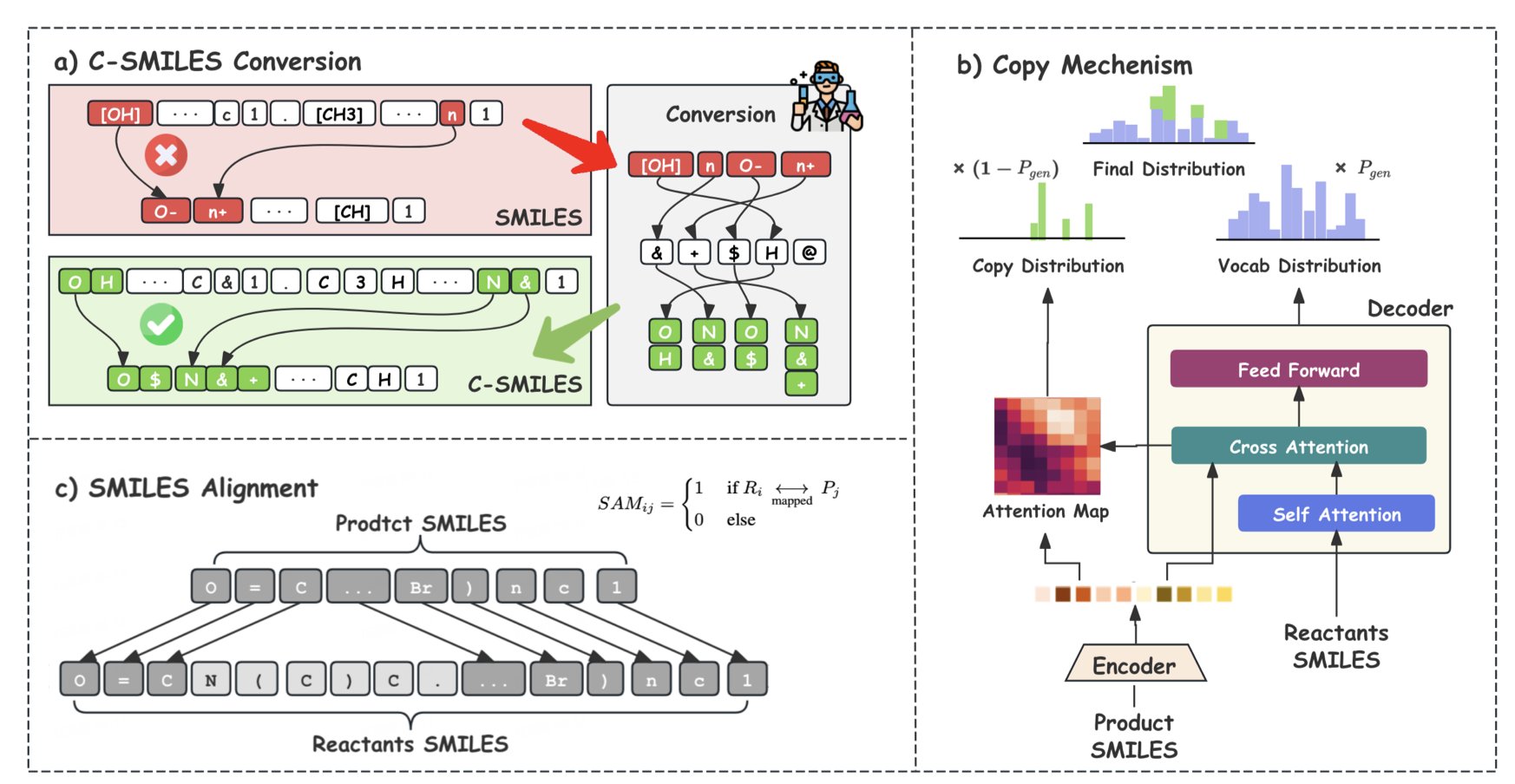

When AI predicts retrosynthesis, it faces a tricky problem: most of a molecule’s structure remains unchanged during a chemical reaction. But traditional models redraw the entire molecule, even if 90% of it is identical to the starting material. This wastes computing power and often introduces chemically impossible errors in the parts that didn’t change.

The authors of this paper came up with a new method.

Their idea is to make the model focus only on the parts that change and simply “copy and paste” the rest.

To do this, they designed a new molecular representation called C-SMILES. Traditional SMILES strings are like long, run-on sentences, making it hard to distinguish key parts. C-SMILES breaks them down into “atom-bond” pairs, like turning a long sentence into a clear list of phrases. This allows the model to easily spot which “phrases” have changed and which have not when comparing reactants and products.

Next comes the core “copy-augmentation” mechanism. At each step of generating a reactant molecule, the model decides: should this part be newly “created” or “copied” directly from the product molecule? It’s like playing a “spot the difference” game where you only need to circle the changes, not redraw the whole picture.

This mechanism narrows the model’s search space, making predictions more efficient. Because most of the structure is copied directly, the chemical validity of the generated molecules is as high as 99.9%. The model almost never makes basic mistakes in stable parts of the structure.

What about the results? On the industry-standard USPTO-50K dataset, the method achieved a top-1 accuracy of 67.2%. This means two out of every three predictions hit the correct answer. For chemists in computational drug discovery, this is a tool that can improve workflow by providing suggestions that are closer to feasible laboratory synthesis routes.

This approach better mimics a chemist’s intuition. When observing a complex molecule, a chemist instinctively identifies the stable, non-reacting scaffold and focuses on the transformation of key functional groups. By using “copy and paste,” this model, in a way, simulates that thinking process. It is beginning to understand the difference between what changes and what stays the same in a chemical reaction.

📜Title: Copy-Augmented Representation for Structure Invariant Template-Free Retrosynthesis

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.16588

2. Cryo-EM Automation: CryoSPARC Makes High-Throughput Drug Discovery a Reality

For structural biologists using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), collecting data is just the first step. The data processing that follows is the most time-consuming and laborious part. Researchers have to screen thousands of micrographs, manually pick millions of protein particles, and then go through multiple rounds of 2D and 3D classification and refinement. This process involves a lot of repetitive work and subjective judgment, much like a craft. It limits the throughput of structure determination and becomes a bottleneck in drug discovery projects.

The CryoSPARC team at Structura Biotechnology developed an end-to-end automated data processing workflow to solve this problem. You can feed the raw microscope data into the pipeline and walk away. When you return, a high-quality 3D density map of the structure might already be finished.

How powerful is this automated workflow?

The researchers tested the workflow on a set of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) datasets, which are known to be difficult to process. GPCRs are one of the most popular target families in drug development, but their structural flexibility and small size pose a serious challenge for cryo-EM data processing.

Out of 21 datasets tested, the automated processing results for 17 of them met or exceeded the resolution and map quality of the published, expert-processed structures.

In some cases, the automated workflow produced higher-quality ligand density maps. A good density map clearly reveals how a small-molecule drug fits into the pocket of its target protein, showing its orientation and interactions with specific amino acids. This precise information is critical for guiding subsequent molecular optimization and determines the success of new drug design.

The Technology Behind the Automation

The workflow’s automation is powered by several new tools:

- Micrograph Junk Detector: Acts like a quality inspector, automatically identifying and removing low-quality images with ice contamination, sample aggregation, or severe defocus.

- Micrograph Denoiser: Reduces noise to make the outlines of protein particles clearer against the background, setting the stage for better particle picking.

- Reference Based Auto Select: An innovative particle-picking algorithm that accurately identifies valid particles automatically.

- Select Volume: After 3D reconstruction, it automatically extracts the target protein from a complex (like a GPCR-G protein complex) for local refinement.

These tools work together to turn steps that once required researchers to repeatedly adjust parameters based on experience into a standardized, automatic operation.

What This Means for Drug Development

This work does more than just simplify a researcher’s job; it changes the model for structure-based drug development.

In Structure-Based Drug Discovery (SBDD) projects, scientists often need to solve the structures of a single target bound to dozens or even hundreds of different compounds. If processing each structure takes weeks of manual effort, the project will stall.

With this automated workflow, high-throughput cryo-EM structure determination is now possible. Imagine a scenario where a synthesis team delivers 10 new compounds. After sample preparation and data collection, the data goes straight into the automated pipeline. Within days, you have the binding modes for all the compounds, allowing you to quickly judge the success of the molecular designs and start the next round. This speeds up the design-make-test-analyze cycle.

The researchers also provide the files for these automated workflows, which users can download, use, and modify in their own CryoSPARC installations. The technology is no longer an exclusive skill of a few experts but a widely accessible tool that will benefit the entire biomedical field.

📜Paper: End-to-end automation of repeat-target cryo-EM structure determination in CryoSPARC

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.17.682689v1

3. A Biosecurity Alert for AI: The Double-Edged Sword of Generative AI

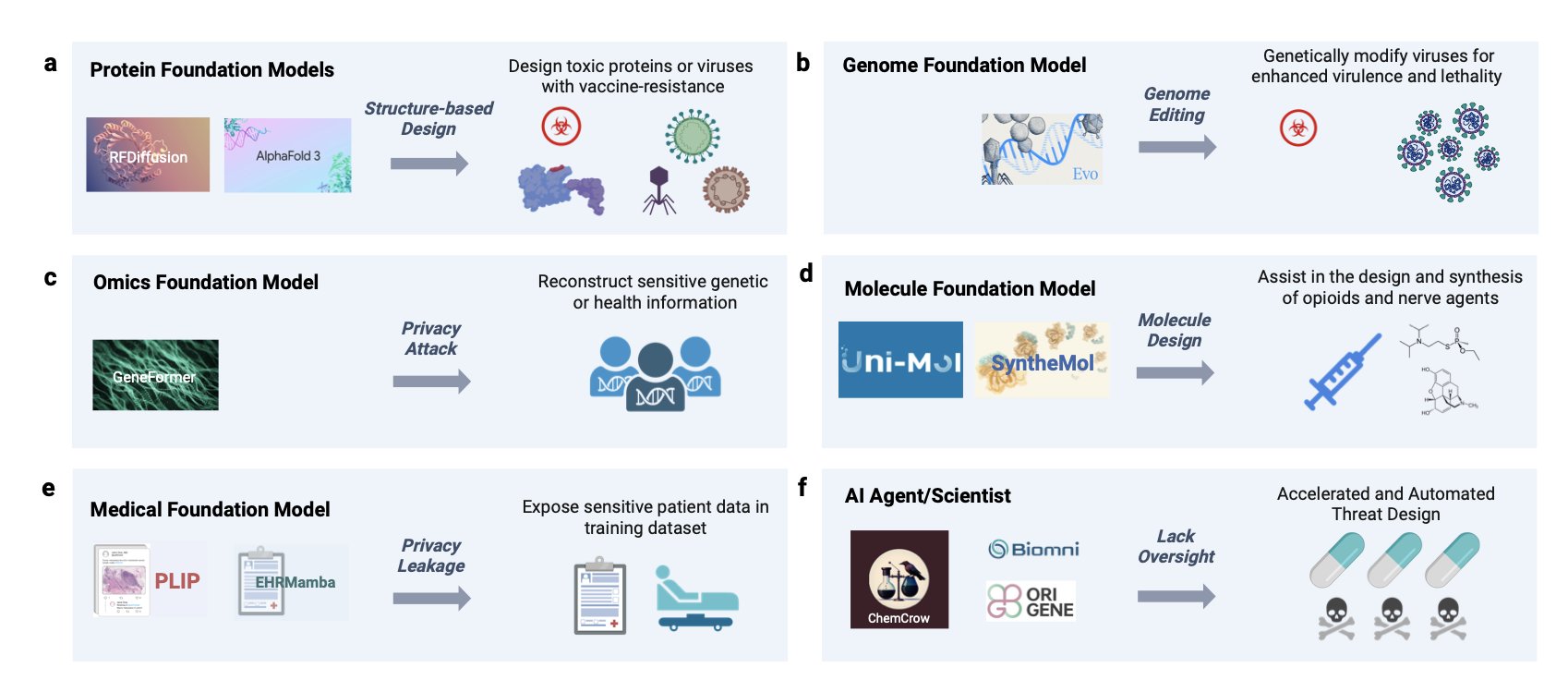

Drug developers have mixed feelings about Generative AI. It can efficiently design new proteins and discover new molecules, speeding up research. But a common concern is that this powerful tool could be used for malicious purposes.

How AI Can Be Misused: From Design Assistant to Potential Threat

The article centers on the “dual-use dilemma” of generative AI. We use it to design therapeutic antibodies; someone else could use it to design toxins. AI learns biological rules from massive datasets and then generates completely new sequences or structures.

Current models understand science, not intent. Even with rules like “do not generate harmful substances,” an attacker can use “jailbreak” techniques to trick it with seemingly harmless prompts. For instance, by claiming to be “researching an antidote,” a user could ask the model to design a molecule that efficiently binds to and blocks a neurotransmitter receptor. The model might then generate a potential neurotoxin.

Escalating Risk: AI Agents That Can Take Action

The risk is growing. The emergence of AI agents allows AI to move from “designing blueprints” to “executing tasks.”

An AI agent could independently plan and carry out an entire experimental workflow: design a dangerous gene sequence online, automatically place an order with a DNA synthesis platform, and then direct a cloud-based automated lab to complete the experiment. The entire process requires almost no human intervention, significantly lowering the technical barrier for creating biological threats.

Data Security: Our Real Defenses Are Becoming Fragile

Data privacy is another often-overlooked risk. The data used to train models—such as proprietary compound libraries, screening data, and clinical trial results—are a company’s core assets. Research shows that large models can “memorize” specific, rare data points during training. If an attacker uses special queries to induce the model to leak this training data, it could lead not only to the loss of trade secrets but also to the design of targeted biological attacks against specific populations.

Industry-Wide Concern and How to Respond

The author interviewed 130 experts from academia, government, and industry. 76% were concerned about the misuse of AI in biology, and 74% believe a new governance framework is necessary.

The article proposes a multi-layered defense strategy.

- Screening at the Source: Remove known harmful sequences and information from the training data.

- Model Alignment: Embed safety and ethical principles into the model’s core logic during development.

- Real-Time Monitoring: After deployment, establish a system to monitor user requests in real-time and block suspicious intentions immediately.

This system must evolve dynamically. As technology advances, so do attack methods. We need to conduct continuous “red-teaming”—simulated attacks—to proactively find and fix the model’s security vulnerabilities, ensuring our defenses keep pace with evolving threats.

📜Title: Generative AI for Biosciences: Emerging Threats and Roadmap to Biosecurity

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.15975

💻Code: N/A

4. ProtoMol: Using Prototypes to Guide Multimodal Molecular Property Prediction

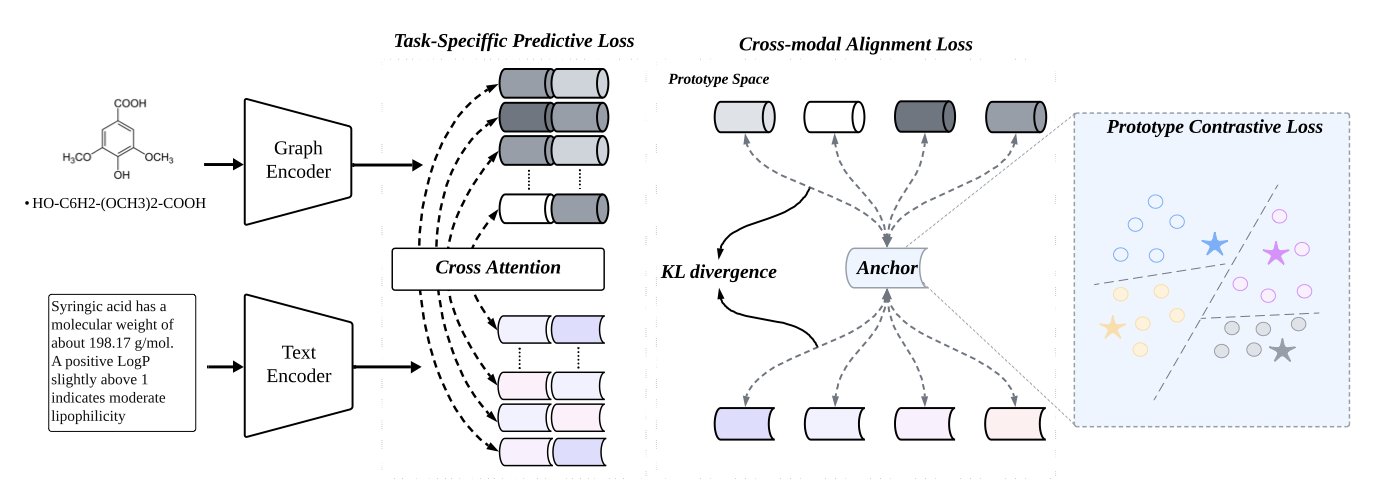

Drug discovery involves diverse data types, from 2D or 3D molecular structure diagrams to text describing biological activity, toxicity, or physicochemical properties from patents and literature. Getting a computer to understand and connect both types of information has been a long-standing challenge.

Existing multimodal learning methods usually merge information only at the final stage, lacking depth. This shallow fusion is like having two experts—one who only understands structures and another who only reads literature—who meet just once to submit a final report without communicating during their analysis. This approach fails to capture the subtle but critical links between structure and semantics.

ProtoMol offers a new solution.

The Core Idea: Establishing a “Common Language”

ProtoMol’s core idea is to create a common frame of reference for molecular graphs and text: a unified semantic space called the “Prototype Space.”

A “prototype” can be understood this way: to predict if a molecule is toxic, you can define abstract “prototype” vectors for the “toxic” and “non-toxic” categories, representing the core features of each class. ProtoMol’s job is to train a model to map both the structural information from a molecule’s graph and the information from its text description into this prototype space.

If a molecule is toxic, both its structure graph and text description, after being encoded by the model, will be located close to the “toxic” prototype in this space. At the same time, the model uses contrastive learning to push molecules from different categories (like toxic and non-toxic) further apart in the space.

How It Works: A Dual-Branch Architecture with Layer-by-Layer “Dialogue”

To achieve this, ProtoMol uses a dual-branch encoder architecture.

- Graph Encoder: Uses Graph Neural Networks (GNN) to extract features from the atoms and bonds of a molecule’s structure.

- Text Encoder: Uses a Transformer model to understand and encode the semantic information in the text description.

The key is that the two branches do not work independently. ProtoMol employs a layer-by-layer bidirectional cross-modal attention mechanism. At each layer of information processing, the graph and text encoders exchange information, “referencing” each other. This step-by-step alignment ensures that low-level features (like individual atoms or words) and high-level features (like functional groups or sentence meanings) are processed in sync.

This layer-by-layer “dialogue,” combined with the unified prototype space, ensures a deep fusion of information from both modalities.

How Well Does It Perform?

ProtoMol was tested on several public benchmark datasets for both molecular property classification and regression tasks. The results showed that its performance consistently surpassed that of current state-of-the-art models.

Ablation studies further validated the model’s key components. Removing either the prototype space or the cross-modal attention mechanism caused a drop in performance, proving that these two designs are critical to its success.

ProtoMol’s modeling approach aligns with a chemist’s intuition. When chemists evaluate a molecule, they mentally match its structural features with known concepts like “lipophilicity” or “carcinogenic group.” ProtoMol’s prototype space mimics this concept-based cognitive process, which may be why it is both accurate and more interpretable. This work offers a new direction for developing more reliable and trustworthy AI tools for drug discovery.

📜Title: ProtoMol: Enhancing Molecular Property Prediction via Prototype-Guided Multimodal Learning

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.16824

5. A Machine Learning Breakthrough: Accurately Predicting Superbug Drug Resistance

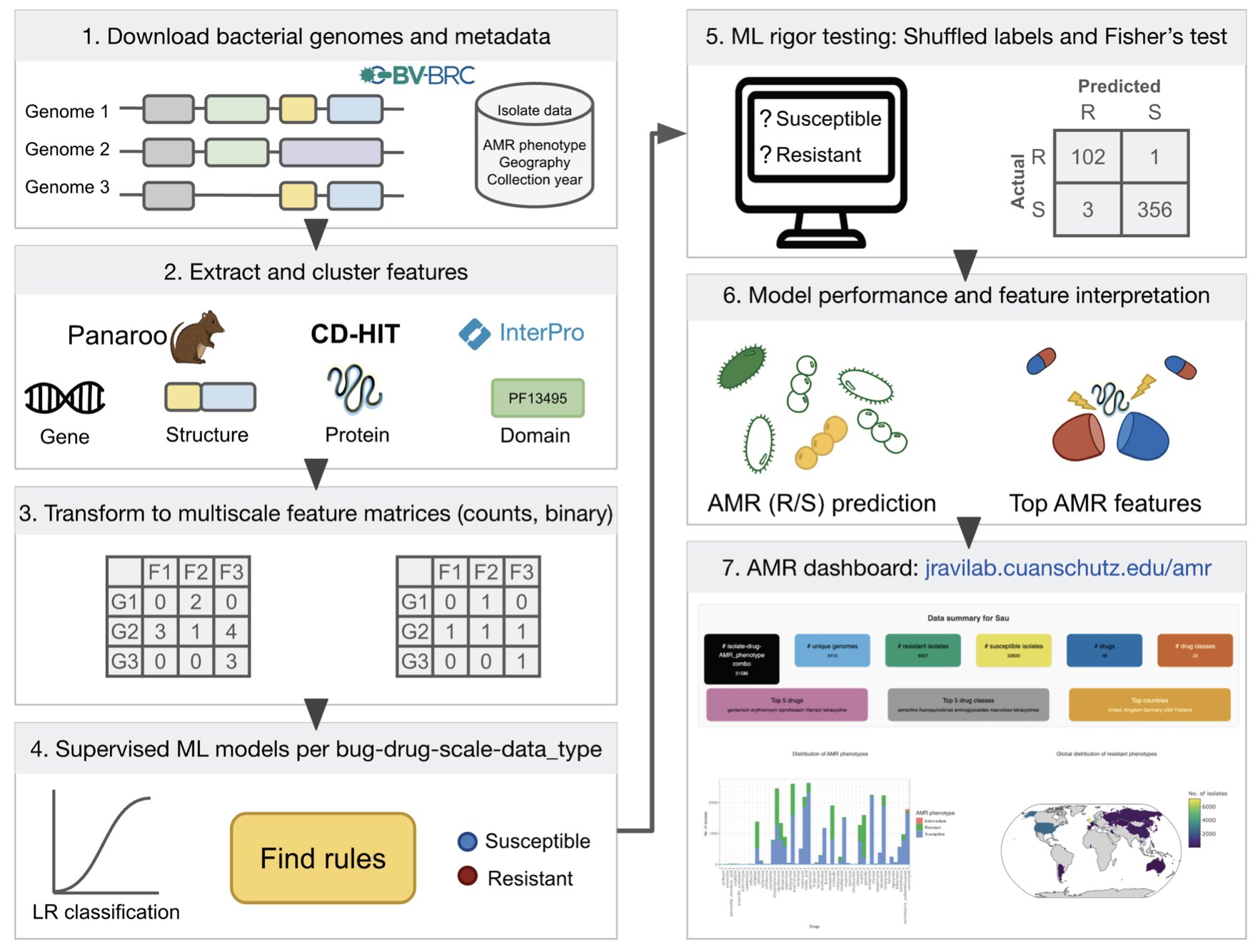

Antibiotic resistance (AMR) is a growing crisis, especially with “superbugs” like the ESKAPE pathogens. Traditional bacterial culture and susceptibility testing are slow, which can delay treatment for critically ill patients. Methods based on sequencing known resistance genes can miss new resistance mechanisms.

This study offers a new approach that moves from identifying single features to creating a comprehensive “resistance profile.”

Here is how it works. The researchers collected a large amount of genomic data from ESKAPE pathogens. They first constructed a pangenome for each bacterial species, which is like a complete gene library for that species. Then, they broke down genes into smaller functional units for analysis, such as protein domains.

This produced features at multiple scales, from the presence of a gene to variations in protein domains. It is like describing a car by not only its make and model but also its tire tread and headlight design, providing much richer information.

Using these features, the researchers trained a logistic regression machine learning model. The model learns which combinations of features, or “signatures,” are highly correlated with resistance to specific antibiotics.

The model’s predictions were highly accurate, with a median Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.89. The MCC is a reliable metric for evaluating classification on unbalanced data. The model performed consistently when tested on data from bacterial strains from different geographical locations and time periods, proving that it learned generalizable rules rather than just memorizing the training data.

The model’s discovery capability is another major highlight. It correctly identified known resistance mechanisms, such as specific enzymes or efflux pumps, which served as a positive control. The model also flagged several new, unreported genes or proteins. These are potential new resistance mechanisms, providing leads for future biological research and drug development.

Finally, the research team packaged the model and its results into an interactive web application. Labs or hospitals worldwide can upload a strain’s genetic sequence and quickly receive a resistance prediction report. This shortens the time from gene sequencing to obtaining clinically relevant information.

Of course, the new candidate genes predicted by the model still need to be validated by wet lab experiments. But the high-quality candidate list it provides allows researchers to focus their efforts more efficiently and narrows the scope of their search.

📜Title: From sequence to signature: Machine learning uncovers multiscale feature landscapes that predict AMR across ESKAPE pathogens

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.03.663053v2