Table of Contents

- MolGenBench reveals a huge gap between current structure-based molecular generation models and real-world drug development needs, calling for more practical evaluation standards and model designs.

- The STELLAR-koff model predicts how long a drug stays on its target more accurately by analyzing the drug molecule’s multiple conformations within the target’s binding pocket.

- The AXIS system combines AI with a “human-in-the-loop” approach to automatically and accurately identify macromolecular crystals, solving a long-standing problem in structural biology.

- This new framework models different protein conformations separately, solving a core problem in AI antibody prediction: it can distinguish between the model’s prediction errors and the protein’s own shape changes.

- Combining protein language models with physics-based calculations allows us to use the complementary biases of both methods to more accurately screen for mutations that enhance protein stability.

1. MolGenBench: Setting a Higher Bar for AI in Drug Discovery

Whenever a new AI drug discovery model is released, it comes with impressive metrics and charts, claiming it can design novel molecules with high activity. But researchers on the front lines always wonder: how useful are these models in a real drug discovery project? The recently released MolGenBench benchmark provides a rather sober answer.

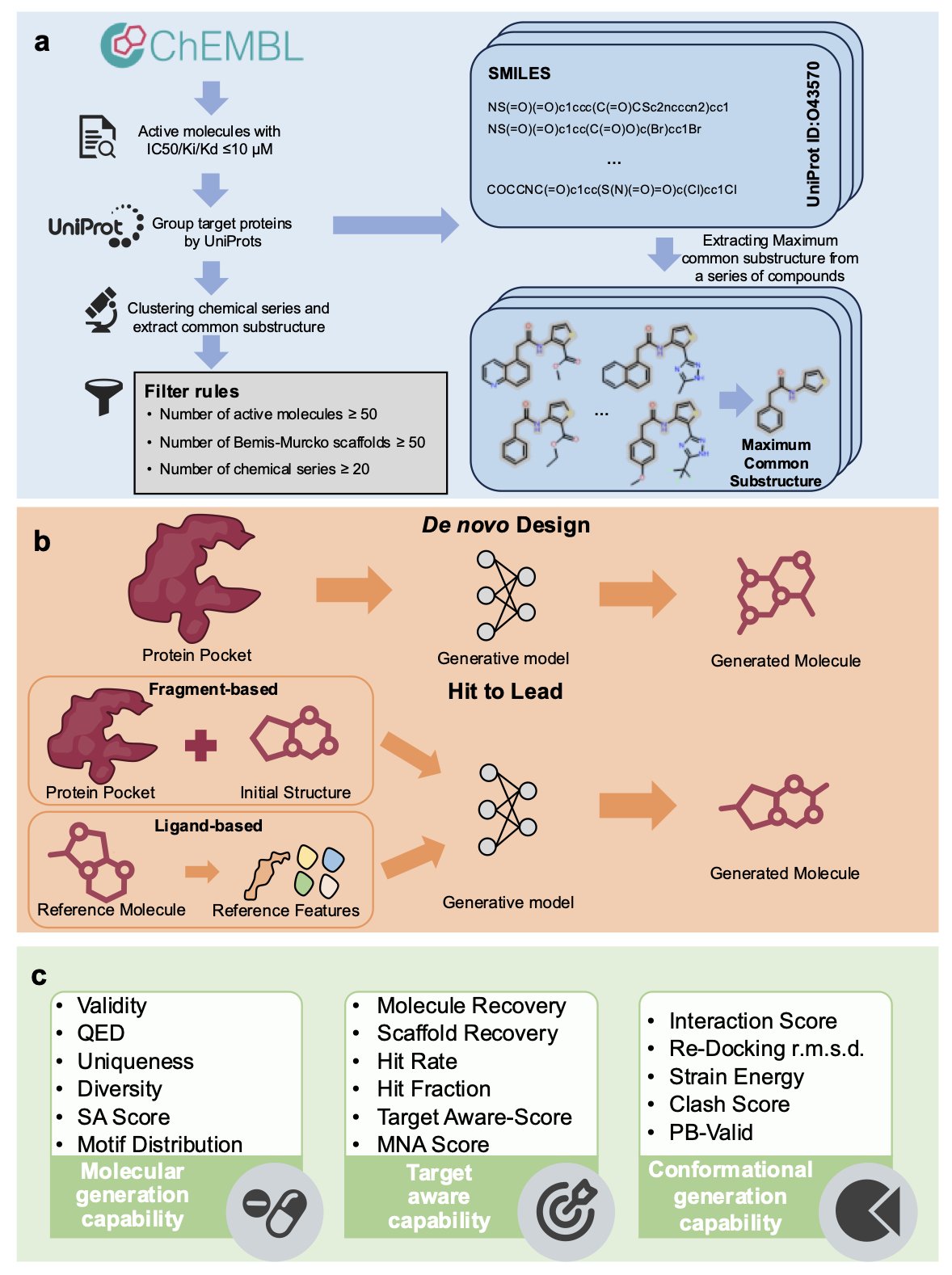

MolGenBench’s core idea is to build an evaluation system that is closer to the real world. Previous benchmarks were like testing students on a few tricky math problems, but MolGenBench is a comprehensive exam. It doesn’t just test a model’s ability to generate new molecules (de novo design), it also includes a critical step: Hit-to-Lead (H2L) optimization. This is a crucial part of drug development, where a known active molecule is finely tuned to improve its activity, selectivity, and other drug-like properties. We have lacked a standard way to measure a model’s performance in the H2L scenario.

The MolGenBench dataset is large, containing 120 protein targets and 220,000 experimentally validated active molecules. Researchers also designed two new evaluation metrics: the Target-Aware Score and the Mean Normalized Affinity (MNA). The first assesses whether the molecules generated by the model are effective only against the intended target, while the second measures the model’s actual ability to improve molecular activity in optimization tasks.

Researchers used this new benchmark to systematically evaluate 10 de novo design methods and 7 H2L optimization methods, covering mainstream technologies like autoregressive models, Diffusion Models, and Bayesian Flow Networks.

The results were not optimistic.

In the basic task of rediscovering known active molecules, most models struggled. The molecules they generated looked novel, but they often strayed from the known effective chemical space. It’s like an architect designing a bunch of wild-looking houses that can’t actually be built.

The models’ ability to use protein structure information was also limited. One surprising finding was that models trained on experimentally solved crystal structures performed better on some tasks than models trained on simulated docking complexes. This shows that the quality of training data is critical; high-quality input leads to reliable output. Current algorithms don’t seem to be able to fully extract useful information from simulated, noisy structural data.

This work serves as a wake-up call for the field. We can no longer be satisfied with achieving high scores on old, oversimplified benchmarks. Drug discovery is a complex system, and AI tools must be tested in scenarios that are much closer to reality. MolGenBench offers a good starting point. It tells us that future models need to be more task-oriented in their design and have more generalizable optimization capabilities. Only then can AI in drug discovery move from an academic concept to a clinical reality.

📜Title: MolGenBench: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Structure-Based Molecular Generation 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.03.686215v1 💻Code: https://github.com/CAODH/MolGenBench

2. How AI Predicts How Long a Drug Binds to Its Target: The STELLAR-koff Model

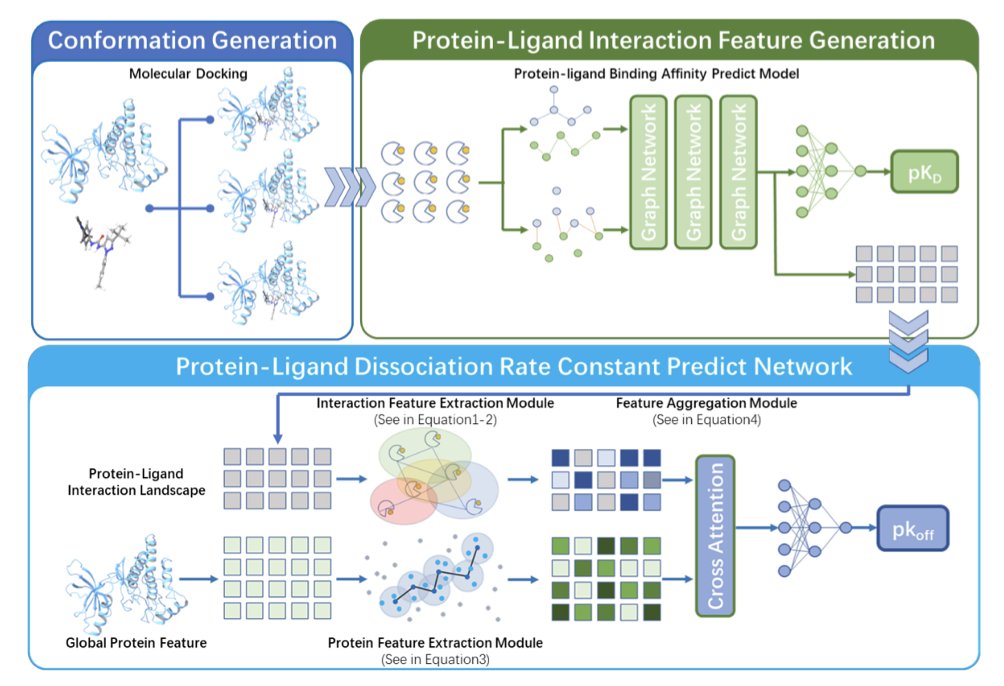

In drug development, it’s not just about how well a drug molecule binds to its target protein, but also how long it stays bound. This duration is measured by the dissociation rate constant (koff). A smaller koff means the drug leaves the target more slowly, potentially leading to a longer-lasting effect. Traditional computational methods usually analyze only a single, static shape of the drug-target complex, but in reality, the molecule is constantly moving within the binding pocket.

From Static Snapshot to Dynamic Video

Traditional methods are like judging a relationship from a single photo, whereas the STELLAR-koff model is like watching an interactive video. It doesn’t look at a single conformation in isolation. Instead, it treats the many possible shapes of the drug molecule inside the protein pocket as a whole, creating an “interaction landscape.” This landscape maps out a series of dynamic shapes, providing richer information.

Using Existing Knowledge

Because high-quality koff data is scarce, training a model to understand this complex landscape directly could easily lead to overfitting. The researchers used a transfer learning strategy. They first used a well-established affinity prediction model to convert each conformation into machine-readable features. This is like teaching a child to recognize wheels and headlights before teaching them to identify a whole car, which improves learning efficiency.

Understanding Spatial Relationships with Graph Neural Networks

After getting the features for all conformations, the model uses an equivariant graph neural network (EGNN) to process this information. EGNNs are good at understanding the relative positions and relationships of objects in three-dimensional space. They can capture the spatial arrangement between different conformations, leading to a more accurate prediction of the final dissociation rate.

The method works well. On a dataset of 1,062 protein-ligand complexes, its predictions had a correlation of 0.729 with experimental values, outperforming previous methods. AI can not only help screen for potentially effective drugs but also predict which molecules will have a longer-lasting effect from a kinetic perspective. This is significant for optimizing drug design.

📜Title: STELLAR-koff: A Transfer Learning Model for Protein-Ligand Dissociation Rate Constant Prediction Based on Interaction Landscape 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.01171v1

3. AI-Powered Crystal Identification: AXIS Puts an End to “Missing the Mark”

In structural biology and drug development, obtaining high-quality crystals is a critical first step. The traditional method relies on researchers spending a lot of time looking for pin-sized crystals under a microscope. This process is tedious, prone to error, and a bottleneck for the entire workflow.

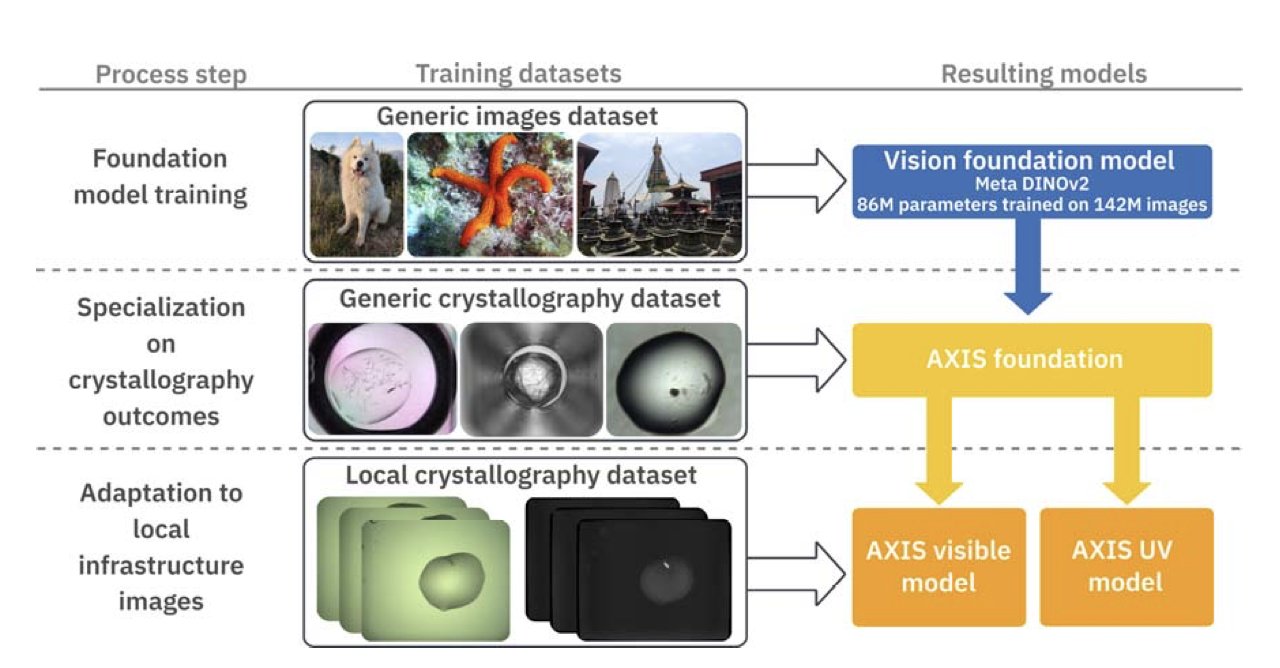

A new system called AXIS brings artificial intelligence (AI) into this process. At its core is the DINOv2 computer vision model. After being trained on MARCO, the largest database of crystallography images, the model identifies crystals more accurately than previous AI models.

What makes the system unique is its “Lab-in-the-Loop” mechanism. The AI first makes a preliminary judgment on the images. Then, a human expert uses CRIMS software to confirm or correct it. The AI learns from every human intervention, quickly adapting to the specific experimental conditions and sample types of a particular lab, allowing it to evolve in a personalized way.

AXIS also uses ultraviolet (UV) light images. Protein crystals fluoresce under UV light of a specific wavelength, which is a strong signal. By combining information from visible and UV light, the performance of the AXIS classifier is improved, especially when identifying tiny crystals.

In real-world tests, AXIS performed as well as or even better than human experts. It not only identifies crystals accurately but can also find some that were previously overlooked or mislabeled. This automated and precise identification capability will speed up the research and development pipeline, from basic research to new drug design. Researchers have already verified its scalability and adaptability at the VMXi beamline at the Diamond Light Source in the UK, demonstrating its potential for use in various high-throughput structural biology platforms.

📜Paper: AXIS: A Lab-in-the-Loop Machine Learning Approach for Generalized Detection of Macromolecular Crystals 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.03.685844v1 💻Code: Not available

4. A New Way for AI to Discover Antibodies: Solving the Protein ‘Shape-Shifting’ Problem

In computer-assisted antibody drug discovery, one problem has always persisted. Proteins are not rigid structures; they constantly move and change shape in solution, existing in multiple conformations. So, when an AI model gives a low score to an antibody, it’s hard to tell if the molecule itself is bad, or if the model “wrongly rejected” a promising molecule that was just in an unfavorable shape.

Traditional methods usually consider only the most stable conformation of a protein or average the prediction results from all conformations, but this loses key information. A molecule might have weak binding in 90% of its shapes but perform exceptionally well in the other 10%. An averaging approach would overlook it.

The “Rank-Conditioned Committee” (RCC) framework proposed in this paper offers a solution.

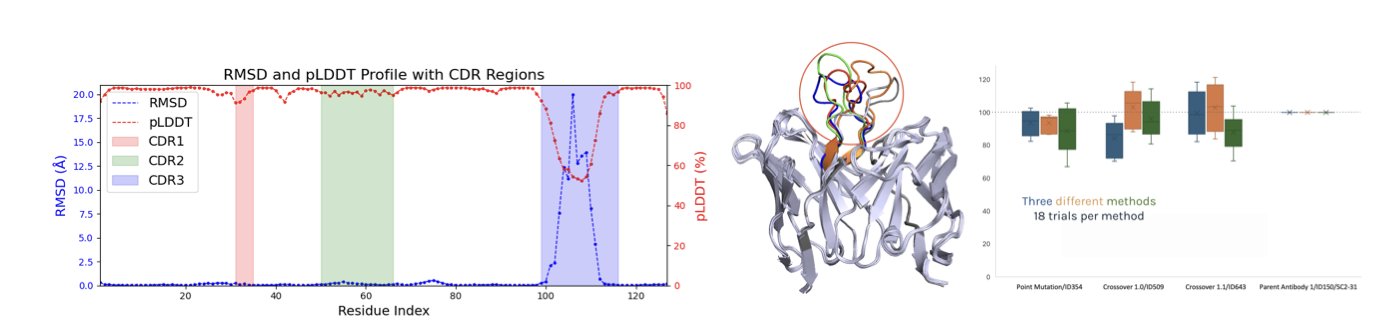

Here’s how it works: First, it generates a series of possible conformations for the target antibody through molecular dynamics simulations. Then, it ranks these conformations based on their energy levels and groups them. For example, the group with the lowest energy and highest stability is “Rank 1,” the next most stable is “Rank 2,” and so on. Next, the framework trains a separate deep neural network “committee” for each rank of conformations. This way, there is one model dedicated to learning the binding patterns of “Rank 1” shapes and another for “Rank 2” shapes.

This design breaks down the problem, allowing the model to distinguish between two types of uncertainty. If a molecule gets scattered prediction scores from the models for all conformation ranks, it means the model itself is not confident about its prediction. This is known as epistemic uncertainty. If a molecule scores high only in a specific favorable conformation but low in others, it means the uncertainty comes mainly from the molecule’s own flexibility. This is conformational uncertainty.

This distinction is very valuable in the “active learning” loop of drug discovery, as it helps to balance exploration and exploitation more intelligently. We won’t easily give up on a molecule because of conformational uncertainty. Instead, we can identify its potential in a specific shape.

The authors tested this method on a SARS-CoV-2 antibody docking case. The data showed that after several rounds of computational screening, the average binding score of the candidate molecules consistently improved. The deep neural network (DNN ensemble) using the RCC framework not only showed the greatest improvement but also had well-controlled variance, indicating that it could efficiently explore new molecules while precisely optimizing existing ones.

For now, this is just a computational validation. The final effectiveness will need to be confirmed with more detailed binding simulations and wet lab experiments. But as a computational strategy, it solves a long-standing pain point in the field, making AI-assisted directed evolution more reliable and efficient.

📜Title: Conformational Rank Conditioned Committees for Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.24974

5. A New Paradigm in Protein Design: Combining the Strengths of AI and Physics

Protein stability is key in drug development. Unstable molecules can shorten a drug’s half-life, reduce manufacturing yield, and increase storage costs. To make proteins more stable, researchers need to modify them. Traditional experimental methods are like finding a needle in a haystack, while computational methods can narrow down the search. There are two main approaches.

The first is physics-based methods (PBM), like the MM/GBSA used in this study. It treats a protein as a three-dimensional structure and uses classical mechanics formulas to calculate the energy change (ΔΔG) after an amino acid mutation. If the energy decreases, the structure is likely more stable, much like an engineer calculating the structural forces on a building. But this model is too simple, especially when dealing with water molecules and charged amino acids, making the results less accurate. It tends to favor mutations involving charged residues.

The second path is Protein Language Models (PLMs), such as Meta’s ESM series. It acts like a biological “linguist,” learning the “grammatical rules” of evolution by studying hundreds of millions of natural protein sequences. The model determines whether a mutation is “grammatically correct”—that is, whether it is common in evolution. PLMs capture the patterns of evolution, but they don’t understand physics. They can’t judge the physical plausibility of a mutation in a specific three-dimensional structure. They therefore favor common stabilizing strategies that enhance the hydrophobic core.

The researchers found that although both approaches have flaws, their flaws are different. The physics model makes mistakes with charges, while the language model is biased towards hydrophobic mutations. Combining the two allows them to complement each other.

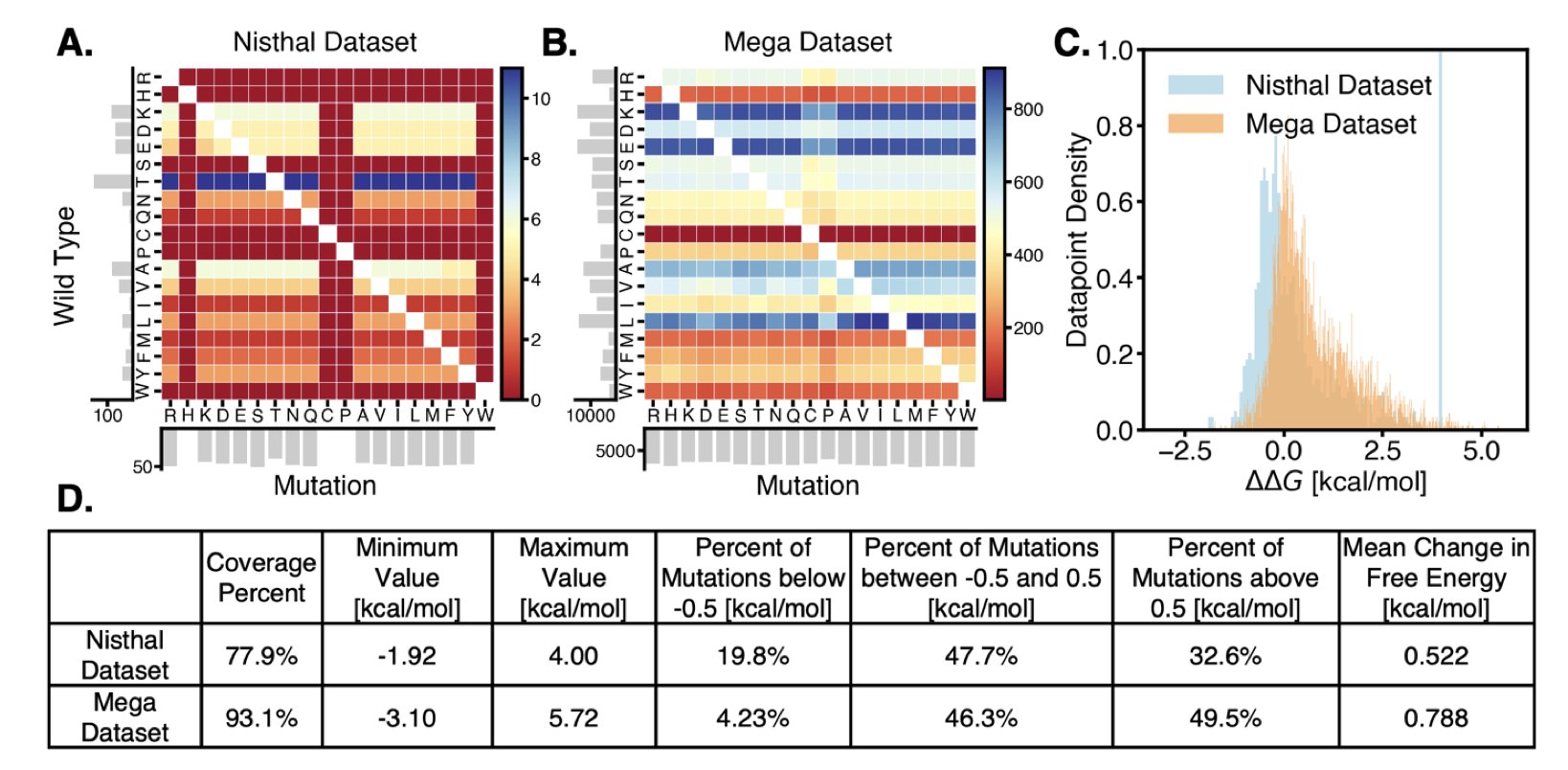

Tests on a dataset containing 180 proteins and nearly 175,000 mutations showed:

This improvement proves that the two methods provide complementary information. If a mutation is approved by both the “physics engineer” and the “evolutionary linguist,” it is very likely to be effective. If only one gives a high score, it might be falling into that model’s biased zone.

For drug development, this provides a more reliable computational tool for protein engineering. Before investing in expensive wet lab experiments, this hybrid method can be used for computational screening to filter out a large number of false-positive candidate mutations. This allows experimental resources to be focused on the molecules with the highest chance of success, speeding up development and reducing costs.

📜Title: Prioritizing Stability-enhancing Mutations using a Protein Language Model in conjunction with Physics-Based Predictions 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.28.683791v1