Table of Contents

- The DiSE model integrates various Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra to simulate a chemist’s reasoning, automating the precise identification of organic compound structures.

- Bio-AMLM dynamically assembles pre-trained biological modules, like building with LEGOs, to create analysis pipelines. This tackles the core weakness of traditional AI models: poor generalization to unknown biological problems.

- Predicting where peptide bonds break allows for the design of mirror-image peptide sequences that are easier to sequence accurately, improving the reliability of data storage.

1. DiSE: AI Decodes Molecular Structures by Thinking Like a Chemist

Figuring out the structure of an unknown compound is complex molecular detective work. Traditional methods rely on chemists’ experience to interpret mass spectrometry and NMR spectra, a process that is time-consuming and prone to error. The DiSE model enables machines to handle this task.

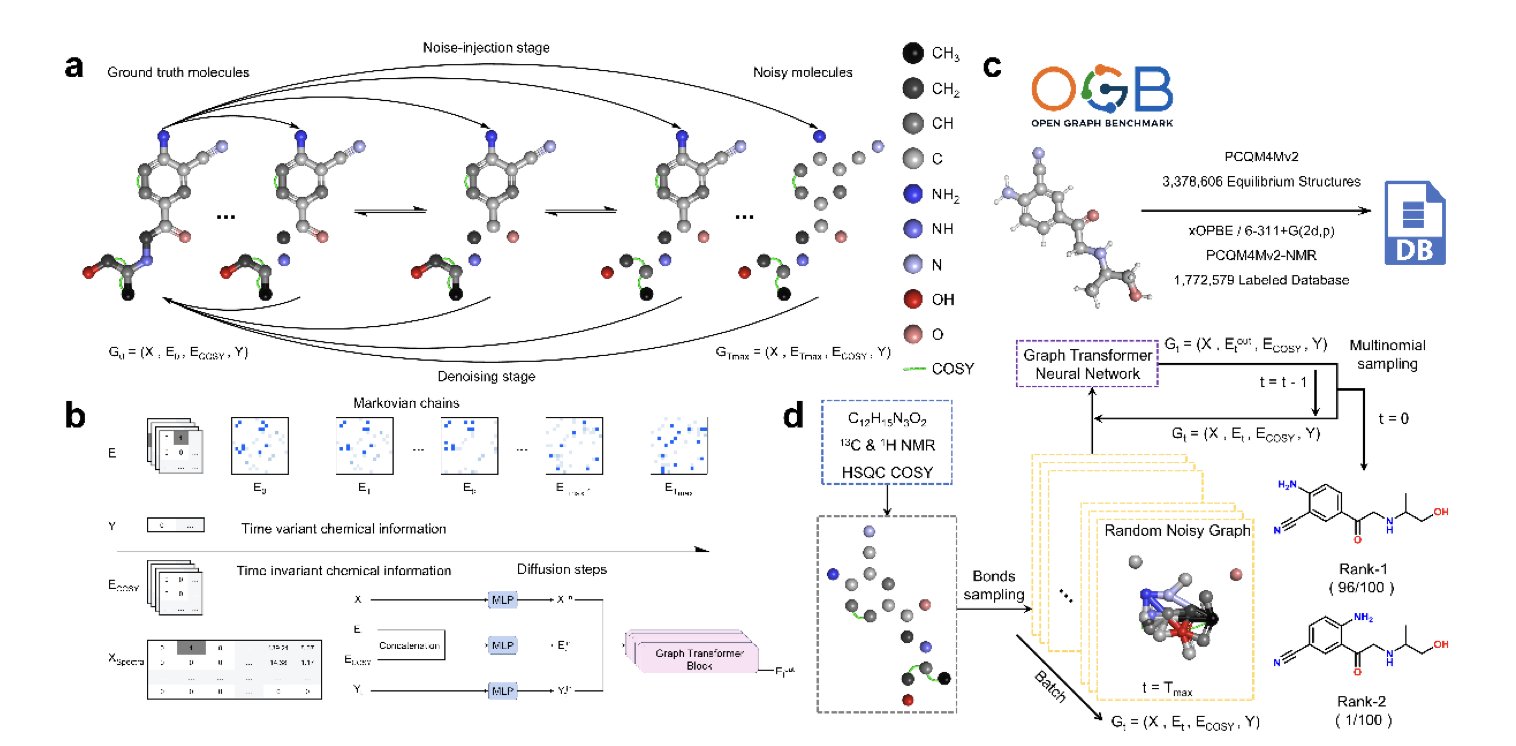

At the heart of DiSE is a diffusion model, a type of generative AI. The process is like putting a scrambled puzzle back together. The model starts with random “noise” and references various spectral data from the compound—mass spectrometry (MS) provides the molecular weight, 1D NMR (¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR) reveals the chemical environment of atoms, and 2D spectra (HSQC, COSY) clarify the connections between atoms—to gradually build the molecular structure.

This approach mimics how a human chemist thinks. When chemists get spectra, they start with key pieces of information, like a specific peak corresponding to a methyl group, and then use correlation signals from other spectra to piece together the complete molecular backbone. DiSE’s iterative denoising process reproduces this step-by-step reasoning. Researchers can watch the model construct the final structure from scratch, making the AI’s decisions transparent.

Previous methods often generated SMILES strings directly, which are text-based representations of molecules. SMILES has strict syntax, and a small error can render the entire molecular structure invalid. DiSE operates directly on the molecular graph, which is more intuitive for chemistry and better at capturing complex relationships between atoms. It effectively uses 2D spectral information from HSQC and COSY, which is crucial for determining the structure of complex molecules and something many traditional methods struggle with.

Researchers tested DiSE on multiple datasets, and the results showed high Top-K accuracy. The model was trained on simulated spectral data but remained robust when handling real experimental data containing noise, proving its potential for solving problems in a real lab setting.

In the future, DiSE could become a core component of automated laboratories, enabling a fully automated workflow from sample analysis to structure elucidation. This would speed up the discovery of natural products and the development of new drugs. The model still has room for improvement, such as supporting more types of elements and spectral techniques, but it points the way for how AI can empower chemical research.

📜Title: DiSE: A diffusion probabilistic model for automatic structure elucidation of organic compounds 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.26231

2. Bio-AMLM: Modular AI Tackles Biology’s Prediction Challenges

A common problem in computer-aided drug discovery is that a model performs well on training data but fails to produce accurate predictions when faced with new, real-world situations. This is the “out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization” problem, a key obstacle holding back AI in biology. Biological systems are too complex for a single, one-size-fits-all model to cover every scenario.

A recent preprint paper introduces the Bio-AMLM framework, which offers a clever solution. Its core idea is to build a modular system composed of specialized functional modules.

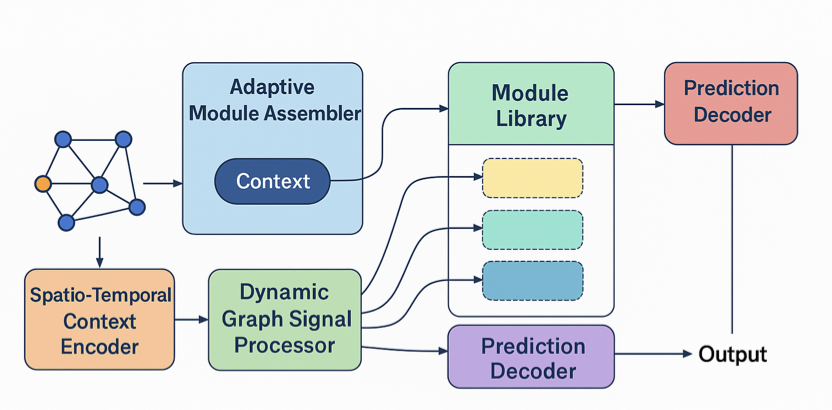

The system works like a project manager. First, it has a “toolbox” filled with pre-trained, single-purpose biological modules. For example, one module specializes in analyzing transcriptomic changes after gene editing, while another is an expert on drug-target interactions. These modules are “specialists” in their respective fields.

Second, the system includes an “Adaptive Inference Planner.” When a new biological question arises, like “What is the toxicity of a new compound on a specific cancer cell line?”, the planner analyzes the context. Then, like assembling LEGO bricks, it selects the right modules from the toolbox and connects them in a logical sequence to create a custom analysis pipeline for that specific question.

For instance, it might first call a “drug absorption” module, then connect a “metabolic pathway” module, and finally link to a “cell apoptosis” module to produce a complete prediction. The entire process is dynamic; a different pipeline is assembled for each different problem.

The advantage of this design is that the model is no longer a rigid black box but a flexible, adaptable analysis system. The paper shows that in benchmark tests for gene editing, drug response, and toxicity prediction, Bio-AMLM consistently outperformed current state-of-the-art single models.

The framework’s interpretability is a major benefit. Because the entire analysis workflow is visible, we can see which biological modules the model used and in what order to answer a specific question. This is valuable for experimental scientists because it reveals a “reasoning path,” not just a “works” or “doesn’t work” conclusion. Scientists can follow this path to design their next validation experiments, improving R&D efficiency.

The framework is still in its early stages. The researchers plan to expand the module library with more “expert modules” from fields like immunology and single-cell transcriptomics. They also intend to use reinforcement learning to make the “planner” smarter. Ultimately, they will validate the model’s predictions with prospective wet-lab experiments.

Bio-AMLM represents a shift in thinking: from pursuing bigger, all-encompassing single models to building an intelligent system that is dynamic, cooperative, and logically clear. This approach more closely resembles how human scientists solve problems.

📜Title: Dynamically Assembling Biological Intelligence to Predict Novel Cellular Phenotypes 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.28.685160v1

3. Mirror-Image Peptide Data Storage: Predicting Bond Breaks to Optimize Sequence Design

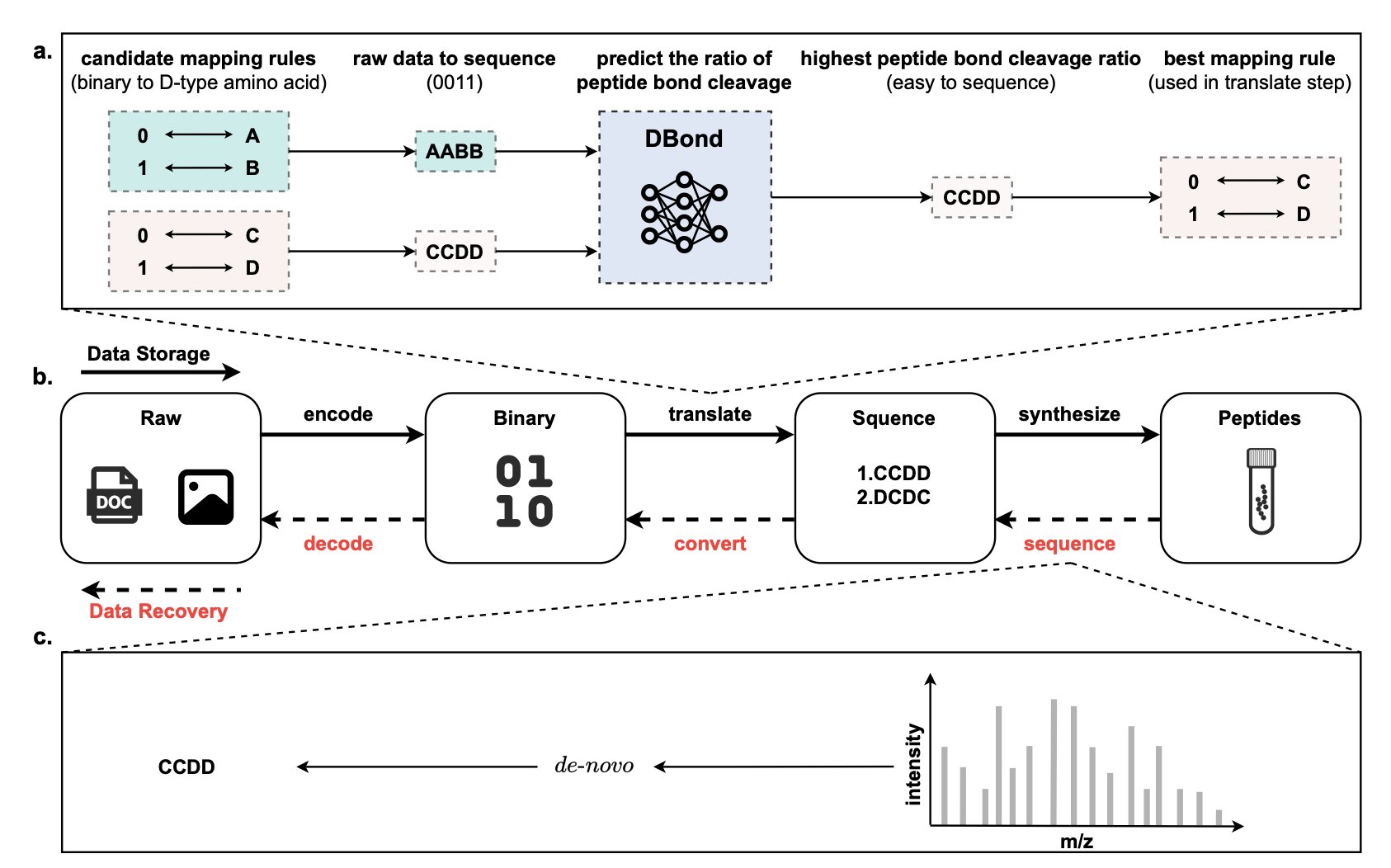

Scientists are searching for data storage methods that are more durable and denser than hard drives, and mirror-image peptides are a promising option. Peptide chains are formed by linking different amino acids, and their sequence can encode information. But accurately reading that information—sequencing—is not easy. During sequencing, a mass spectrometer breaks the peptide chain and analyzes the fragments to determine the original sequence. If the chain breaks easily at some points but is unusually stable at others, sequencing becomes difficult.

To solve this problem, researchers set out to design peptides that are “easy to read.”

First, they needed to figure out under what conditions peptide bonds are likely to break. The team built a dataset called MiPD513, containing 513 mirror-image peptides and over 477,000 tandem mass spectra, to create a database of peptide bond cleavage behavior. They then developed an algorithm, PBCLA, which automatically extracted about 12.5 million labeled instances of whether a peptide bond broke or not from the mass spectra, providing data for machine learning.

Next, the researchers trained a deep neural network model named DBond. This model considers the peptide sequence, physicochemical properties, and environmental parameters from the mass spectrometry analysis to predict the probability of each chemical bond in the peptide chain breaking.

The results showed that DBond’s predictions were accurate. A “single-label classification” strategy, which treats the cleavage of each peptide bond as an independent event, performed best. Using DBond’s predictions, people can design peptide sequences that avoid structures leading to ambiguous sequencing. Instead, they can prioritize sequences with clear, easily identifiable cleavage patterns. This ensures the accuracy and efficiency of data readout, bringing mirror-image peptides a step closer to becoming a viable medium for long-term, high-density data storage.

📜Title: Optimizing Mirror-Image Peptide Sequence Design for Data Storage via Peptide Bond Cleavage Prediction 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.25814v1