Table of Contents

- The PLMDA-PPI model introduces residue contact prediction to improve protein interaction forecasts. It reveals the physical mechanisms of interaction and shows strong generalization ability with novel proteins.

- A new model accurately predicts blood-brain barrier permeability using only molecular fingerprints, providing a simple, interpretable tool for central nervous system (CNS) drug screening.

- Deep learning models, especially the Wasserstein Autoencoder (WAE), excel at generating diverse and effective new antimicrobial peptide (AMP) sequences, offering a new tool to combat drug-resistant bacteria.

1. AI Predicts Protein Interactions: A Dual-Attention Mechanism Marks a New Step Forward

Predicting Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) is fundamental to drug discovery. Usually, all we have is a protein’s amino acid sequence. Traditional methods rely on sequence alignment, which fails when dealing with novel protein sequences. It’s like judging if two people will be friends based only on their resumes, ignoring whether their personalities and interests actually match.

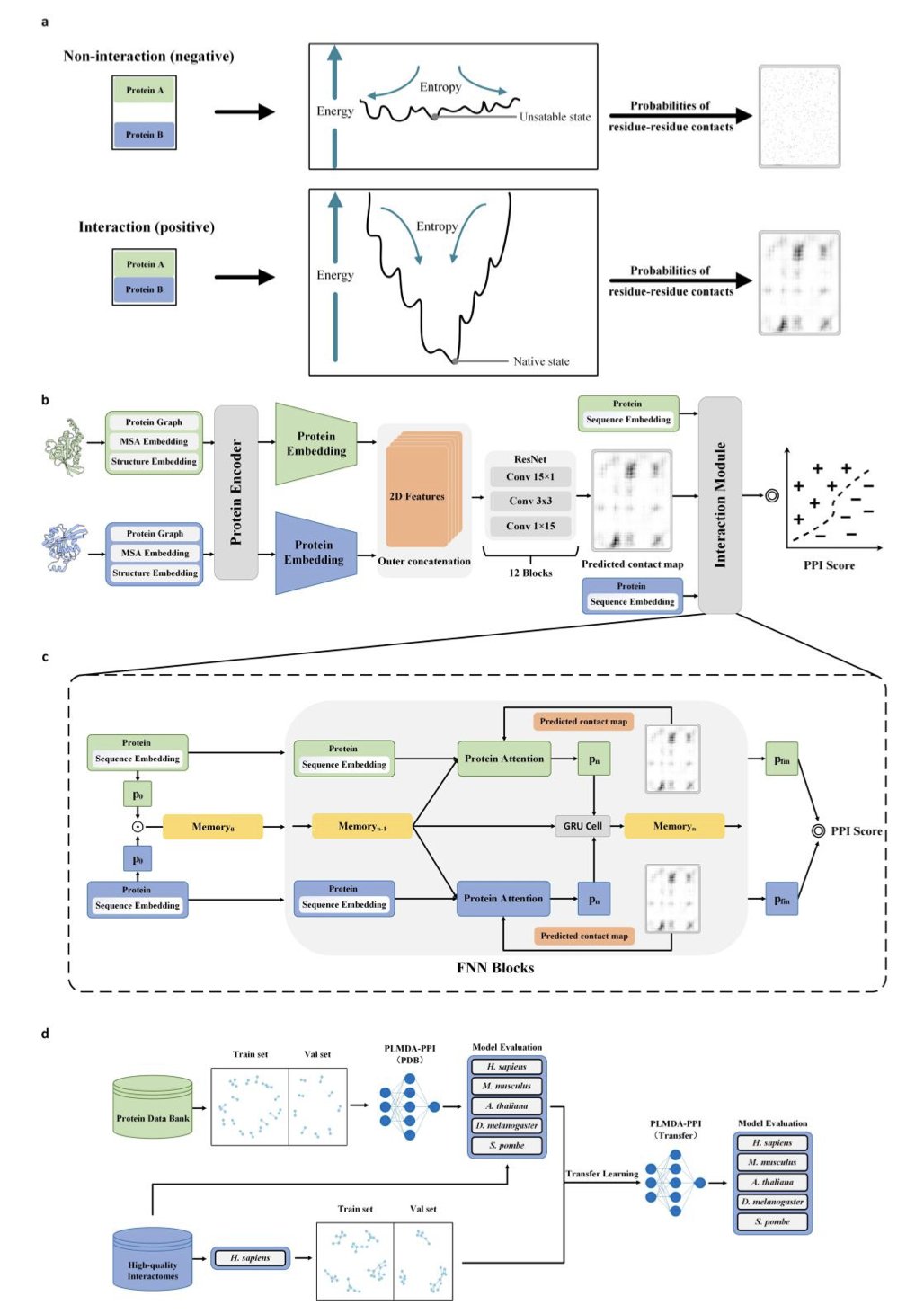

The PLMDA-PPI model offers a new way of thinking. It doesn’t just ask, “Will these two proteins interact?” It also predicts, “Which specific amino acid residues will they use to make contact?” This is like not only determining if two people can be friends, but also identifying the common topics they’ll connect over.

To do this, the researchers designed a clever model architecture. They took protein pairs with known 3D structures and clear contact sites from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to use as the “correct answers” for training the model.

At the model’s core is a Dual Attention module that works like this:

- Residue Contact Prediction: The model first predicts which pairs of amino acid residues from the two protein sequences are most likely to be in close spatial contact.

- Interaction Judgment: The model then uses these predicted “contact points” as key clues to determine if the two proteins interact overall.

This design forces the model to learn the physical basis of protein interactions—the contact patterns at the residue level. It’s no longer just memorizing that proteins with similar sequences will bind. Instead, it learns to recognize the key structural features that drive binding.

The results proved the method’s strength. When tested on new proteins with sequences very different from the training set, PLMDA-PPI far outperformed methods like D-SCRIPT and Topsy-Turvy, which rely on sequence information. Its performance was even better than AlphaFold2-Complex, a method that requires massive computational resources for structure prediction, and it was much faster.

The researchers also ran a fine-tuning experiment. After training the model on human PPI data, they found its accuracy in predicting PPIs in other species (like yeast and fruit flies) also improved. This suggests the model learned universal biophysical principles that apply across species, not just rules for one specific species.

This tool is valuable for drug development. It can screen for potential interacting protein targets and directly point out the likely binding interfaces. This provides specific guidance for designing small-molecule or peptide drugs to control these interactions, much like having a precise treasure map.

📜Title: Mechanism-Aware Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction via Contact-Guided Dual Attention on Protein Language Models 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.04.663157v4

2. New AI Model Predicts Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Using Molecular Fingerprints

In central nervous system (CNS) drug development, you always have to deal with the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), the gatekeeper. For a molecule to enter the brain and do its job, it has to get past the BBB first. For decades, we’ve relied on rules of thumb and physicochemical descriptors (like lipophilicity and polar surface area) to predict whether a molecule can pass, but these methods have always felt indirect.

A new study offers a more direct approach. Researchers built a machine learning model that directly uses a molecule’s “fingerprints” as input.

You can think of a molecular fingerprint as a checklist of a molecule’s structure. It lists all the tiny chemical fragments the molecule contains, like whether it has a benzene ring or a carboxyl group. The model directly analyzes this raw structural information. The advantage is that the model learns patterns from the molecular structure itself, without needing to pre-judge which physicochemical properties are important.

The researchers used the XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) algorithm and applied the SMOTE technique to handle the imbalanced dataset. Since only a minority of molecules in a drug library can cross the BBB, SMOTE ensures the model isn’t biased by the large number of negative examples.

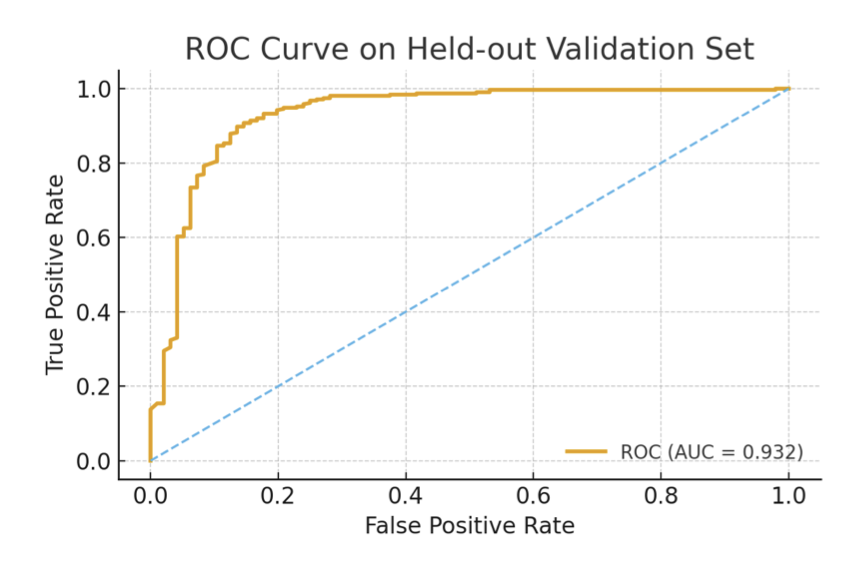

The model achieved a cross-validation ROC-AUC score of 0.897 and 0.932 on an independent validation set.

Beyond its accuracy, the model’s validation process and interpretability are even more valuable. The researchers tested the model with some familiar molecules. For example, caffeine and diazepam (Valium) are typical CNS drugs, and the model correctly predicted they could cross the BBB. For dopamine and L-Dopa, the model determined they could not cross via passive diffusion.

This result aligns with chemical intuition. L-Dopa can’t enter the brain directly and requires a transporter protein, which is central to Parkinson’s disease treatment. The fact that the model can make this distinction shows it has learned the underlying chemical logic of passive diffusion.

The model’s value also lies in its explainability. It can clearly point out which molecular “fingerprints,” or specific chemical substructures, have the biggest impact on BBB permeability. This gives medicinal chemists concrete design ideas. If the model indicates a certain group is a barrier to entry, they can try modifying or replacing it in the next round of molecular design.

The model currently focuses on passive diffusion—a molecule’s ability to cross cell membranes on its own—and cannot yet handle molecules that require active transporter proteins. Future research will involve integrating transporter data or information on molecules’ 3D conformations.

This work provides an efficient, reproducible, and interpretable baseline model. It can be directly applied in early-stage virtual screening pipelines to speed up the discovery of promising CNS drug candidates from vast molecular libraries.

📜Title: Fingerprint-Based Explainable Machine Learning for Predicting Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.25.684495v1

3. AI Designs Antimicrobial Peptides: The WAE Model Stands Out

Antibiotic resistance is a growing crisis, and we urgently need new solutions. Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) are a promising option. They are naturally occurring short proteins that can effectively fight pathogens. Traditionally, discovering and optimizing these peptides is slow and difficult. Deep learning, especially generative models, is now accelerating this process.

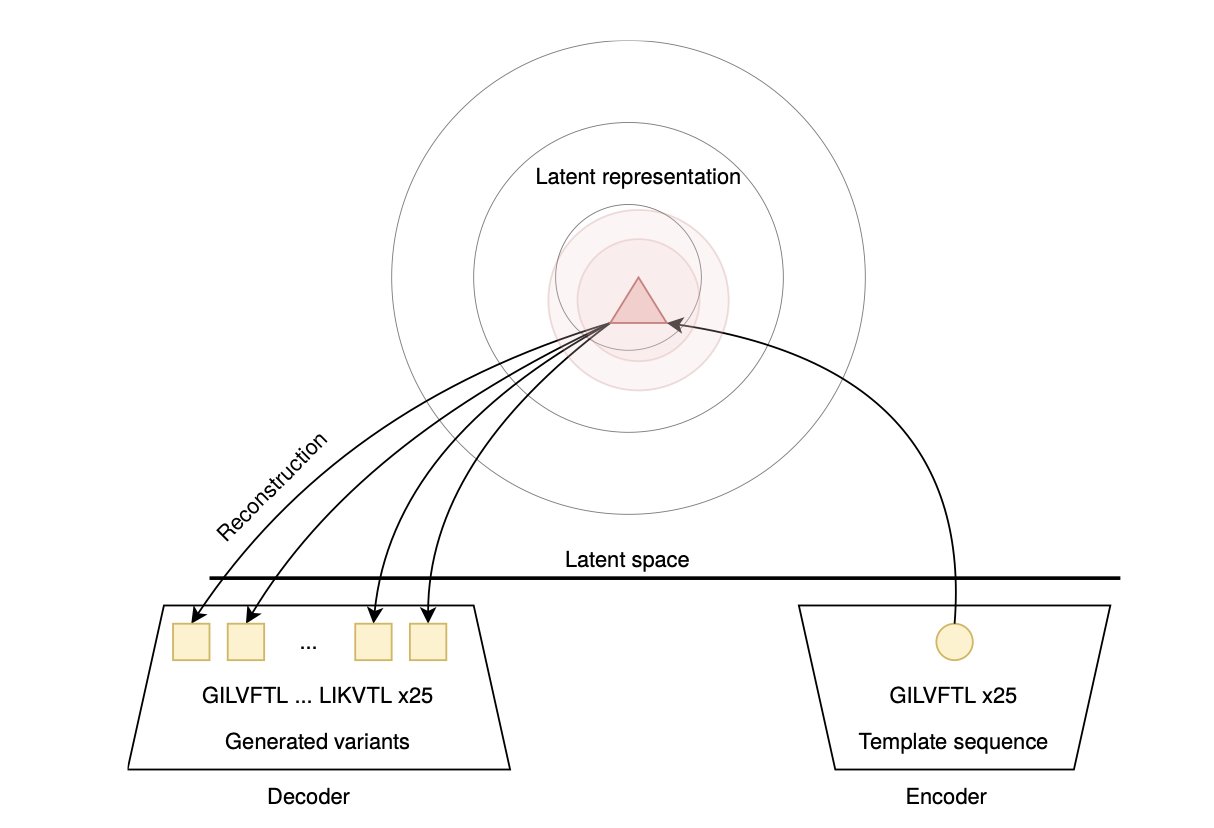

The process is like training an AI to write poetry. First, we train it on a large number of known active antimicrobial peptide sequences, letting it learn their “grammar” and “style.” Then, we ask it to “create” entirely new peptide sequences, hoping to find candidates that are better than existing drugs.

This study compared several mainstream generative models:

The results showed that the WAE model performed the best.

You can imagine the task of these models as searching for treasure in a vast “peptide sequence space.” The VAE model tends to dig in a small, precise area around known treasure spots (the training data). The new sequences it generates are very similar to known ones. While they might be effective, they lack novelty.

The WAE model explores a much wider area. It isn’t limited to known regions and dares to venture into more distant, uncharted territory. This allows it to generate more diverse and structurally novel peptide sequences. Although the risk is higher—some sequences might not work—this exploratory nature makes it more likely to discover truly new drug candidates with breakthrough potential. The data confirmed that WAE maintained the key properties of natural active peptides while introducing just the right amount of sequence diversity.

RNNs and Large Language Models take a different approach. They “write” peptide chains one amino acid at a time, like a text generator. This method can also produce effective sequences, but it’s less flexible than WAE in controlling global structure and diversity.

This work shows that there is no one-size-fits-all model for designing peptides with AI. If the goal is to fine-tune a known, effective peptide, a conservative strategy like VAE might be more suitable. If you want to find entirely new mechanisms of action or chemical backbones from scratch, a more exploratory model like WAE is a better choice.

AI is becoming a powerful partner in peptide drug discovery. The success of the WAE model shows its potential to balance innovation with practicality, adding hope to our fight against superbugs.

📜Title: Generative models for antimicrobial peptide design: auto-encoders and beyond 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.29.685317v1