Table of Contents

- A new method combines a polarizable force field and advanced sampling techniques to realistically simulate water dynamics in binding pockets, improving the accuracy of protein-ligand binding free energy predictions.

- The MaSIF-PMP model uses geometric deep learning to show that a protein’s surface “shape” is key to membrane binding, offering a new perspective for designing drugs that target peripheral membrane proteins.

- CombiMOTS combines multi-objective optimization with fragment-based drug design to generate dual-target molecules that are both active and synthesizable.

1. To Calculate Binding Free Energy, First Deal With the Water in the Protein’s Pocket

In drug discovery, predicting how tightly a small molecule binds to a target protein—its binding free energy—is key to determining its potential. But accurately predicting this with a computer has always been hard. The problem often comes down to water.

A protein’s binding pocket is full of water molecules, and they are active participants. When a drug molecule enters, some water molecules are displaced, and the rest rearrange to form new hydrogen-bond networks. The energy change from this process is a major part of the total binding free energy.

Common classical force fields, like AMBER or CHARMM, treat water molecules as rigid spheres with fixed charges. This simplified model struggles to accurately describe the delicate water networks in a binding pocket. To address this, the study used the AMOEBA polarizable force field. You can think of it as giving water molecules “sensors.” When the surrounding electric field changes, the water molecule’s electron cloud and charge distribution also change. This model is closer to physical reality and can accurately describe the electrostatic interactions between water, the protein, and the ligand.

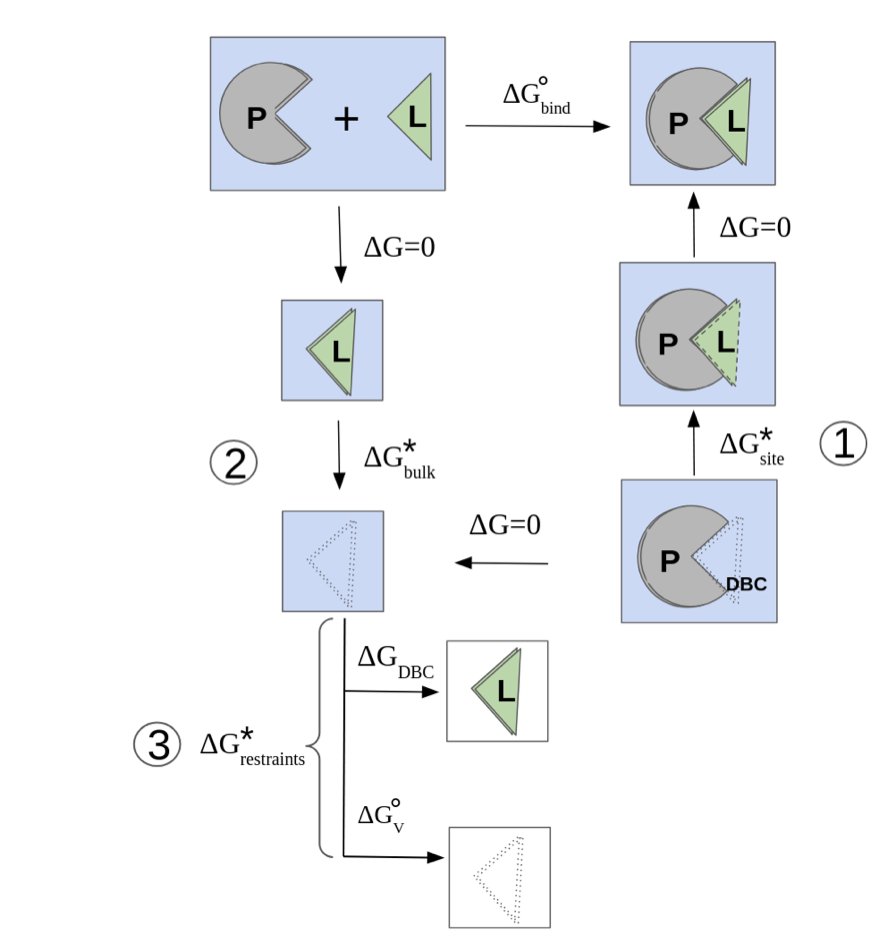

With a more accurate force field, the next challenge is to efficiently explore all possible water molecule configurations. This is a huge sampling space, and using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations directly is like looking for a needle in a haystack. The researchers used a combined approach: Lambda-ABF-OPES.

Here is how it works: 1. First, it uses lambda-dynamics, an alchemical free energy calculation method, to smoothly “turn on” or “turn off” the ligand’s interaction with its environment. 2. Then, it introduces two enhanced sampling techniques: Adaptive Biasing Force (ABF) and On-the-fly Probability Enhanced Sampling (OPES). They act as guides, directing the simulation to explore high-energy but important regions, such as the transition states of water rearrangement.

This method does not require defining Collective Variables for the water molecules themselves, which avoids practical difficulties and makes it more generally applicable.

The researchers tested the method on a series of protein-ligand complexes, including complex systems where the ligand is buried deep in the pocket. The calculated binding free energies matched well with experimental values. For the TAF1(2) bromodomain, the method accurately calculated the affinity and revealed how key water molecules in the pocket influence ligand binding through their dynamic behavior. This shows the method gives accurate numbers and provides mechanistic insights.

This work addresses a core problem in computational drug chemistry—the solvation effect—by combining an accurate physical model (AMOEBA) with an efficient sampling algorithm (Lambda-ABF-OPES). In early-stage drug development, accurately predicting molecular binding affinity can speed up the screening and optimization of lead compounds and reduce trial-and-error costs.

📜Title: From Water Networks to Binding Affinities: Resolving Solvation Dynamics for Accurate Protein-Ligand Predictions

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.17.683050v1

2. New AI Model MaSIF-PMP Accurately Predicts Protein-Membrane Interactions

In drug development, Peripheral Membrane Proteins (PMPs) are a tricky class of targets. They lack fixed binding pockets and interact directly with the constantly changing cell membrane. Predicting this binding interface is like trying to describe the exact sway of a boat on a rough sea.

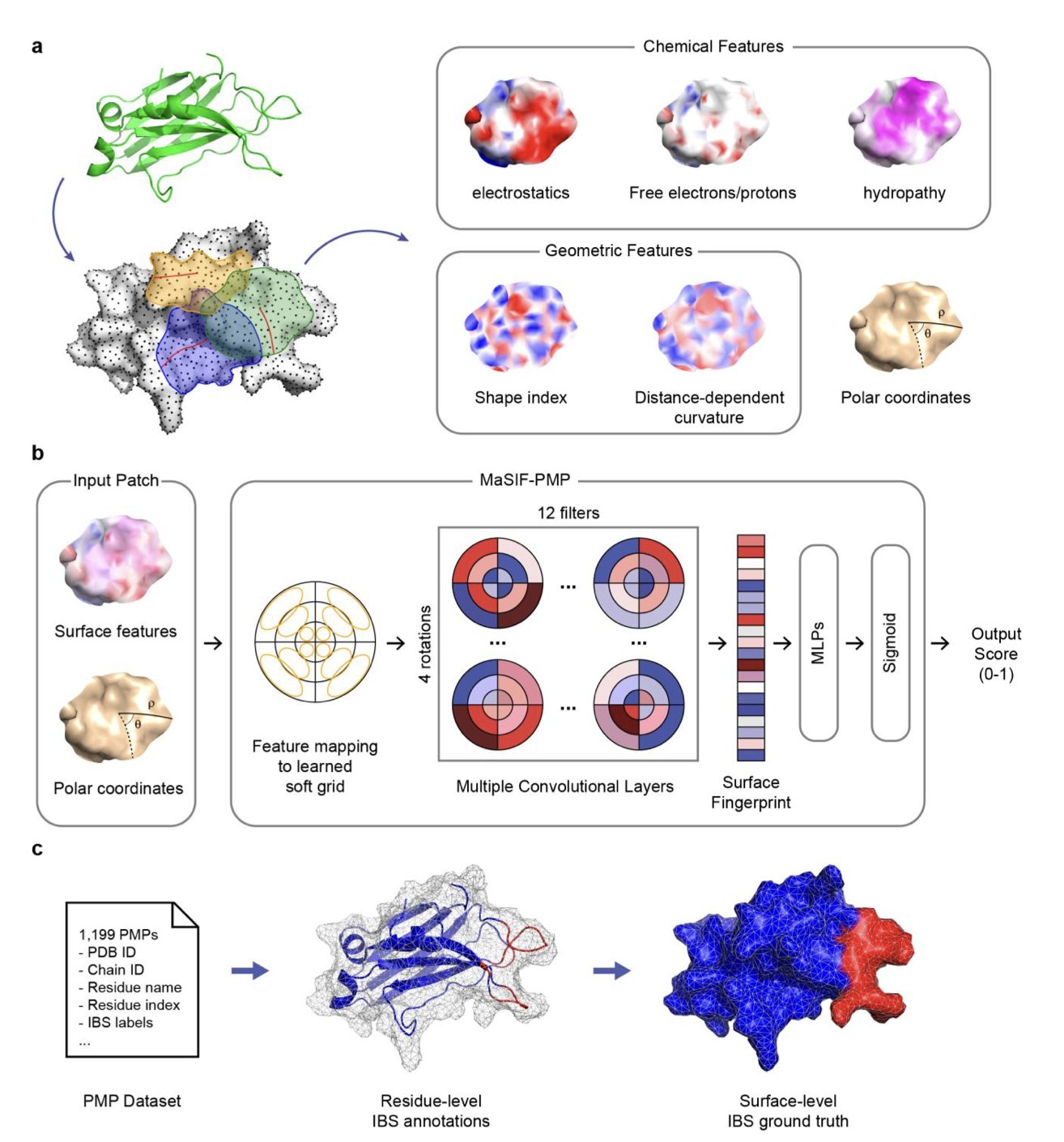

A geometric deep learning model called MaSIF-PMP offers a new approach. We can think of this model as an AI trained to recognize the 3D topography of a protein’s surface. The model focuses on the geometric features of the protein surface, such as bumps, grooves, and curvature.

This study found that the binding of peripheral membrane proteins to the cell membrane is determined mainly by geometry. The researchers confirmed this with feature ablation experiments. When they removed chemical features from the MaSIF-PMP model, the prediction accuracy dropped only slightly. But after removing geometric features, the prediction results got much worse. This proves that whether a protein can bind to the cell membrane depends mainly on whether its surface shape is a good match, much like a key’s shape must fit the lock before its material matters.

Static protein crystal structures are not enough to make accurate predictions because both proteins and cell membranes are constantly moving. To verify and refine the predictions, the researchers used Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

They ran simulations using the HMMM (highly mobile membrane-mimetic) simplified membrane model. This model captures the core fluid properties of a cell membrane but at a much lower computational cost than a full cell membrane simulation. The MD simulations allowed the researchers to observe the dynamic process of proteins approaching and binding to the cell membrane. This dynamic information confirmed MaSIF-PMP’s predictions and also helped correct inaccurate labels in the training data, improving the model’s performance.

For drug developers, the value of this tool lies in its direct predictions. MaSIF-PMP outputs a “heatmap” of the protein surface, highlighting the most likely binding regions. This map allows us to identify potential drug-binding sites. It provides specific guidance for designing small molecule drugs that regulate protein-membrane interactions, helping drug development move from “guessing” to “precise targeting.”

📜Title: Decoding protein–membrane binding interfaces from surface-fingerprint-based geometric deep learning and molecular dynamics simulations

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.14.682447v1

3. AI Generates Dual-Target Molecules and Guarantees They Can Be Made

Discovering dual-target drugs is like walking a tightrope. A molecule needs to bind to two targets at once, meet various drug-likeness requirements like solubility and permeability, and ultimately be synthesizable. Many molecules designed by computational models look perfect but are often abandoned by chemists because they cannot be made.

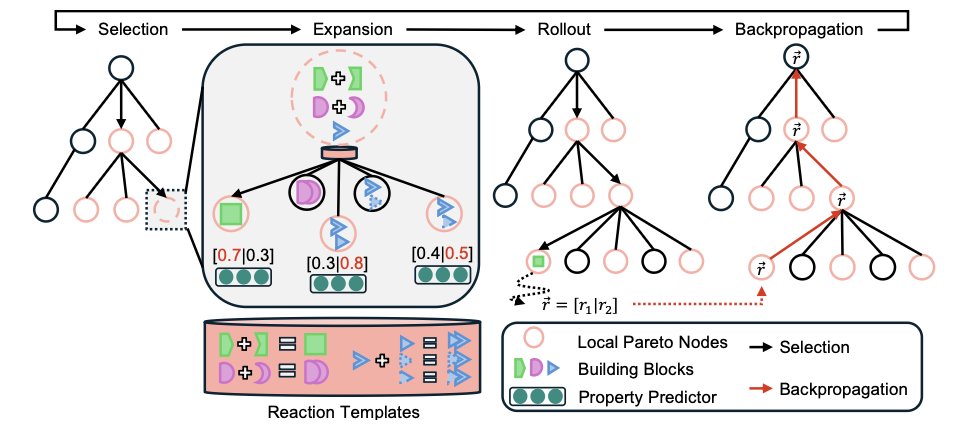

The CombiMOTS method aims to solve this core problem by building “synthesizability” into the molecule design process from the very beginning.

Here is how it works.

First, the method’s core is the Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search (PMCTS) framework. In molecule design, improving affinity for a target might decrease solubility; such multi-objective conflicts are common. PMCTS explores many molecule-building paths at the same time and keeps all “non-dominated” solutions. A non-dominated solution is one for which no other solution is better in all objectives. In the end, the algorithm provides a set of molecules on the “Pareto front,” which represent the best trade-offs between different goals for the development team to choose from.

The method guarantees synthesizability by using a fragment-based approach. The chemical fragments it uses to build molecules map directly to the Enamine REAL Space database. This database contains billions of virtual compounds that can be quickly synthesized using established chemical reactions. As a result, every molecule CombiMOTS puts together has a mostly clear synthetic route from the start. This connects computational design with laboratory synthesis and avoids designs that only work on paper.

The researchers tested the method on dual-target combinations like GSK3β-JNK3, EGFR-MET, and PIK3CA-mTOR. The results showed that compared to existing methods, the molecules generated by CombiMOTS were better in terms of novelty, diversity, and the balance of pharmacological properties.

This framework is also extendable. More quantifiable optimization goals, such as selectivity and toxicity, can be added. This approach of integrating multi-objective optimization with synthesizability from the start makes AI-assisted drug design an effective tool that helps chemists solve real problems.

📜Title: CombiMOTS: Combinatorial Multi-Objective Tree Search for Dual-Target Molecule Generation

🌐Paper: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mlresearch/v267/main/assets/southiratn25a/southiratn25a.pdf