Table of Contents

- GQVis is a large-scale dataset built for genomics, designed to train AI models to turn natural language commands directly into complex, professional visualizations.

- DeepChem-DEL is a standardized, open-source toolkit that solves the problem of fragmented and hard-to-reproduce data analysis workflows for DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs), making machine learning in the DEL field simpler and more reliable.

- Odyssey replaces traditional attention with an evolution-inspired “consensus” mechanism, creating a 100-billion-parameter protein language model that can efficiently generate functional proteins with both sequence and structural information.

1. GQVis: Generating Genomics Visualizations with Natural Language

In genomics research, making sense of massive datasets is a major challenge. To turn data into a meaningful chart, a researcher usually needs to write R or Python code and know exactly which type of plot to use. This process is tedious and creates a barrier for exploratory data analysis.

Now, you might just need to tell your computer: “Show the splicing of gene A in two cell lines and label the exons.” A Sashimi plot could then be generated automatically. This is the future that the GQVis dataset aims to create.

Why does genomics need a dedicated dataset?

General-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs) can’t meet the specialized needs of genomics visualization. Genomics data has its own unique “visual language.”

For example, to show long-range interactions between genomic regions, researchers use a circular layout. To observe alternative splicing in RNA-seq data, a Sashimi plot is the most direct way. General models haven’t learned these domain-specific charts, so they can’t generate them.

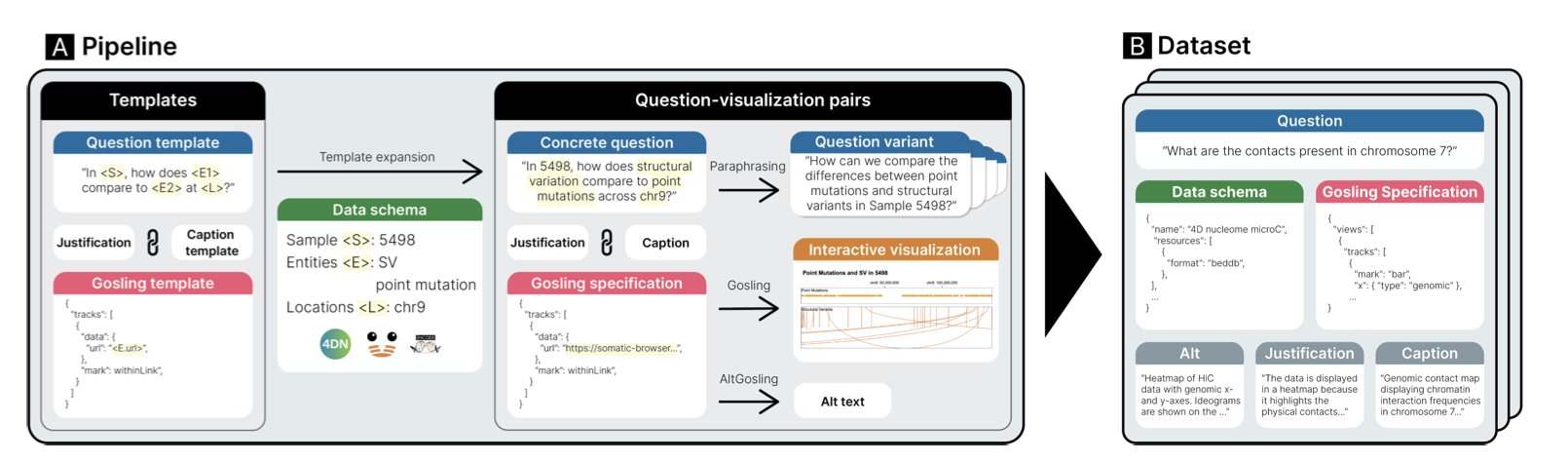

The creators of GQVis matched real data from large public databases like 4DN, ENCODE, and Chromoscope with these specialized plot types, building a dataset with over 2.2 million data points. This approach is designed to teach AI models the “jargon” of genomics.

Understanding the plot, not just drawing it

A core goal of this project is to teach AI why a certain visualization is chosen.

Each sample in the dataset includes not only the natural language command and the final chart but also an explanation of the “design rationale.” For instance, “A Sashimi plot was chosen because the user wanted to compare splicing patterns across different samples.” This is like a senior scientist guiding a novice, explaining the thought process behind an action. After learning these rationales, an AI is more likely to make scientifically logical judgments when facing new problems.

Making data analysis a conversation

Scientific discovery is a process of continuous exploration. A researcher might start with an overview, spot a pattern, zoom in on the details, and finally overlay other data for validation.

GQVis includes a large number of “multi-step query chains” in its dataset to simulate this process. For example: 1. “Show the overall structure of a specific chromosome.” 2. “Zoom in to region p13 on chromosome 15.” 3. “Overlay the ChIP-seq signal for a certain protein in this region.”

After being trained on this kind of data, future AI models can better support exploratory analysis. You can have a continuous conversation with the model, dynamically adjusting the visualization and making the data analysis experience feel closer to actual research habits.

GQVis is currently a high-quality “textbook” for training models. The next step is to use this dataset to fine-tune Large Language Models and establish evaluation standards to judge whether the AI-generated charts are scientifically accurate. This is a step toward making AI a capable assistant for genomics researchers.

📜Title: GQVis: A Dataset of Genomics Data Questions and Visualizations for Generative AI

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.13816

2. DeepChem-DEL: An Open-Source Framework to Standardize DEL Data Modeling

A unified workflow with a modular design

Screening a DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) is like panning for gold in a muddy river. You can search through hundreds of millions or even billions of molecules, but most are just useless silt. The real “gold”—active hit compounds—is hidden in massive amounts of sequencing data. The current challenge is that every lab has a different method for “panning,” using a wide variety of software and algorithms. This makes it hard to compare and validate results. A method that works for one project might fail in another.

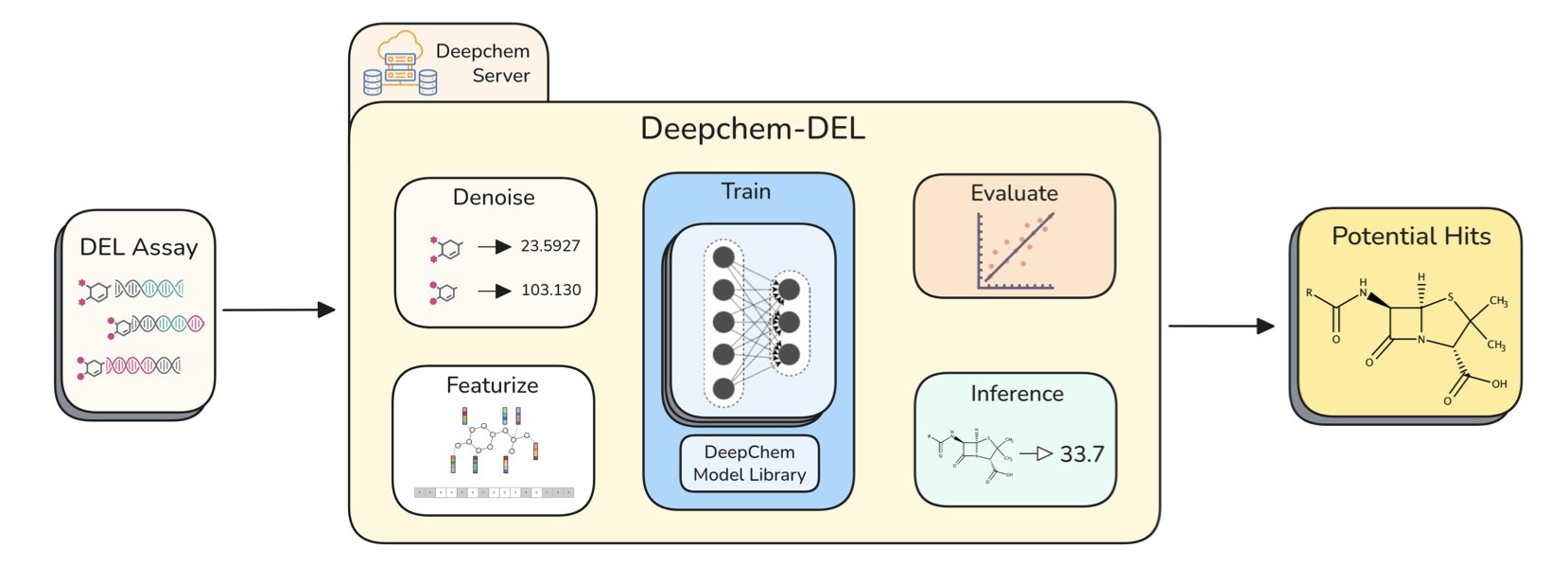

To solve this chaotic situation, Stanford’s Pande Lab and X-Chem have released DeepChem-DEL. It provides a standardized set of data analysis tools and workflows, integrating the entire process from data denoising to model prediction. It is also designed to be flexible and integrates seamlessly with DeepChem Server, supporting large-scale parallel computing in the cloud.

Step 1: Clean the data to separate noise from signal

The first step in DEL screening is processing raw sequencing data, where “denoising” is key. Raw data is full of random noise from the sequencing process. If not handled properly, this noise can drown out the truly valuable signals.

DeepChem-DEL provides a clear denoising workflow with two core methods built in:

- Unify Signal: This calibrates signals using a Poisson enrichment score. It’s like setting a baseline brightness for all the “rocks,” so only those that are significantly brighter are considered potential gold.

- Amplify Signal: This enhances the signal-to-noise ratio by aggregating the counts of similar structural fragments (disynthons). This is like finding several small flecks of gold clustered together, which suggests a larger deposit might be nearby. It uses the “clustering” effect to amplify weak signals.

Step 2: Focus on the whole molecule, not just its parts

DEL molecules are assembled from several chemical fragments (synthons). Many past models only analyzed combinations of two fragments (disynthons), but a molecule’s overall properties are not just a simple sum of its parts.

Experimental data shows that using three fragments (trisynthons) to represent a molecule almost always results in better model performance than using just two. It’s like trying to identify a car from its wheels, door handle, and engine parts, which gives you more information than looking at just the wheels and door handle.

Step 3: Analyze each case specifically, as there is no silver bullet

The research also found that there is no single “optimal” data processing method for all cases.

Tests on the kinase targets DDR1 and MAPK14 showed that for DDR1, the trisynthon model without signal unification performed best for classification. For MAPK14, the trisynthon model with signal unification performed better.

This finding is important for researchers. It shows that different targets have different properties and molecular preferences, so using a fixed workflow for all projects is not practical. The value of DeepChem-DEL is that it provides a flexible platform, making it easy for researchers to test different strategies and find the optimal solution for a specific target.

An open platform to accelerate drug discovery

The core contribution of DeepChem-DEL is its openness and standardization. In the past, many companies treated their DEL data analysis workflows as trade secrets, which slowed progress for the entire field.

Now, this open-source, reproducible benchmarking framework gives everyone a common starting point. Academic researchers can enter the field more easily, startups can quickly build analysis platforms, and large companies can use it to validate and compare their internal methods. This openness will promote the development and application of new algorithms, ultimately accelerating DEL-based drug discovery.

📜Title: DeepChem-DEL: An Open Source Framework for Reproducible DEL Modeling and Benchmarking

🌐Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-f11mk

3. The Odyssey Model: Replacing Attention with “Consensus” to Reconstruct Protein Evolution

As protein language models get larger, the attention mechanism in the Transformer architecture becomes a bottleneck because its computational cost grows quadratically. A 102-billion-parameter protein model would have to get around the attention mechanism.

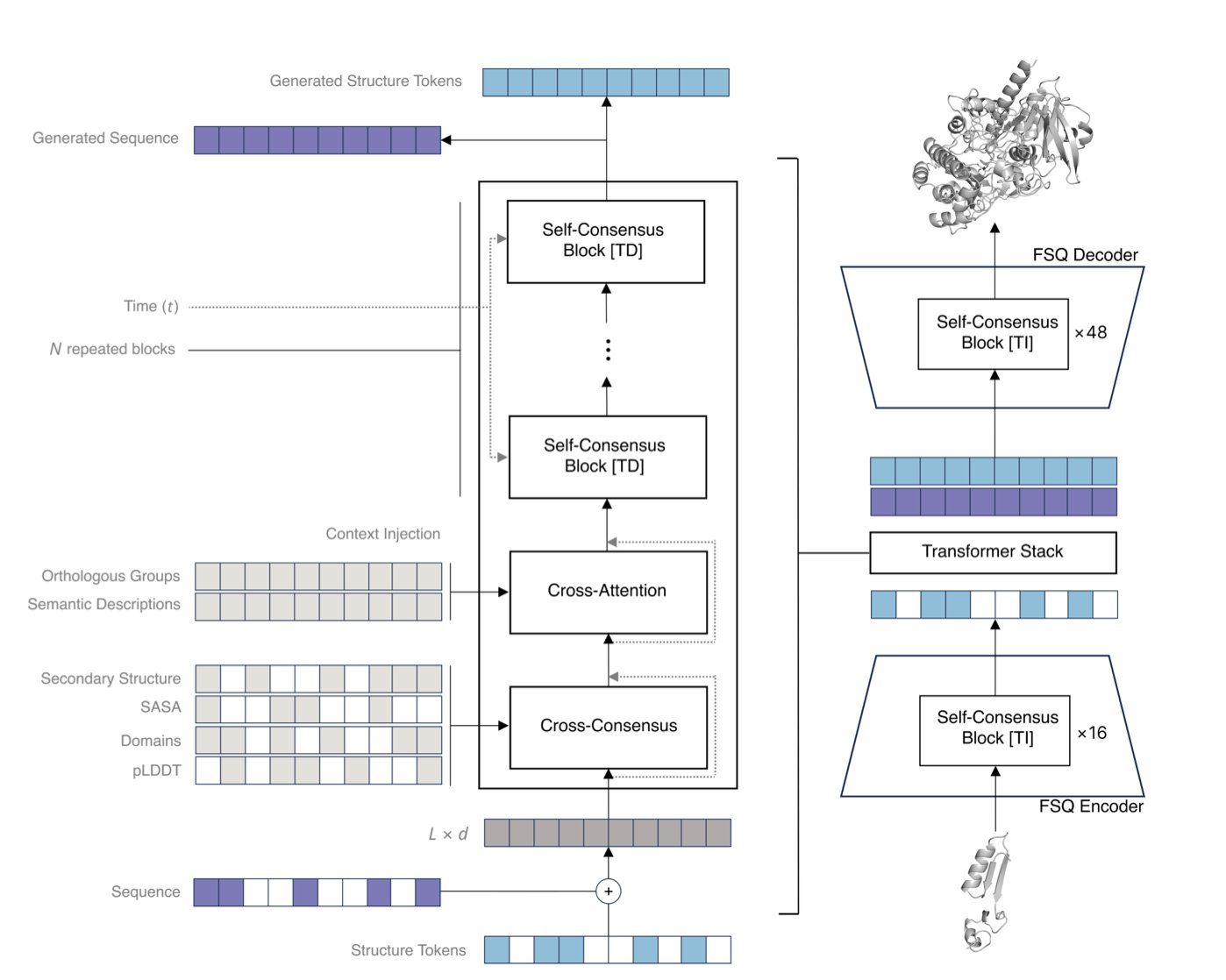

Odyssey’s answer is a “Consensus” mechanism. In traditional attention, every amino acid has to communicate with every other amino acid, which requires a huge amount of computation. In the consensus mechanism, an amino acid first reaches a local consensus with its neighbors. These local consensuses are then passed up layer by layer to form a global understanding. This approach is computationally efficient and makes a model with over 100 billion parameters possible. It also more closely resembles the physical process of protein folding: local secondary structures form first, then assemble into a complete 3D conformation.

With the computational architecture solved, the next problem is how to make the model understand both sequence and 3D structure at the same time. A protein’s atomic coordinates are continuous values, but language models process discrete tokens. Odyssey uses a technique called a Finite Scalar Quantizer (FSQ). This is like laying a fine grid over the 3D space and approximating the precise coordinates of each atom to the nearest grid point. This converts the continuous coordinates into a series of discrete “codes” that the model can process like text. The paper’s data shows this method performs better than other existing approaches.

The training method is also different. Many models use Masked Language Modeling, where some amino acids are hidden and the model has to predict them. Odyssey uses Discrete Diffusion instead. This process simulates evolution: first, a normal protein sequence is randomly “damaged,” and then the model learns how to “repair” it. Through repeated “damage-repair” cycles, the model is forced to learn the deep rules behind protein sequence and structure. The results show that for tasks that require predicting both sequence and structure, the discrete diffusion method has a lower perplexity, proving the model learns better.

Generating beautiful structures is not enough; proteins need to have a biological function. In the final step, the researchers used a D2-DPO alignment technique to fine-tune the model. They showed the model pairs of samples and told it which protein had better activity and which had worse. This way, the model learned to distinguish between good and bad, understanding the intrinsic connection between sequence, structure, and biological function. As a result, when designing entirely new proteins, the model can generate molecules that are more likely to have the desired function.

Odyssey’s approach provides a path for building larger protein design models that have a better understanding of biology. A model that can master the “sequence-structure-function” code is a key tool for designing new antibodies, enzymes, or other protein drugs from scratch.

📜Title: Odyssey: Reconstructing Evolution Through Emergent Consensus in the Global Proteome

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.15.682677v1