Table of Contents

- The CGBENCH benchmark shows that current Large Language Models are still unreliable for interpreting clinical genetics literature, with serious problems in distinguishing evidence strength and generating hallucinations.

- The DemoDiff model understands molecules in terms of “functional groups,” enabling efficient few-shot learning. It can perform complex molecular design with just a few examples, outperforming general-purpose models thousands of times its size.

- The LLaDR framework combines the semantic understanding of Large Language Models with biomedical knowledge graphs to improve the accuracy and robustness of drug repurposing predictions.

1. AI Reading Genetics Papers: New Benchmark CGBENCH Reveals Critical Flaws

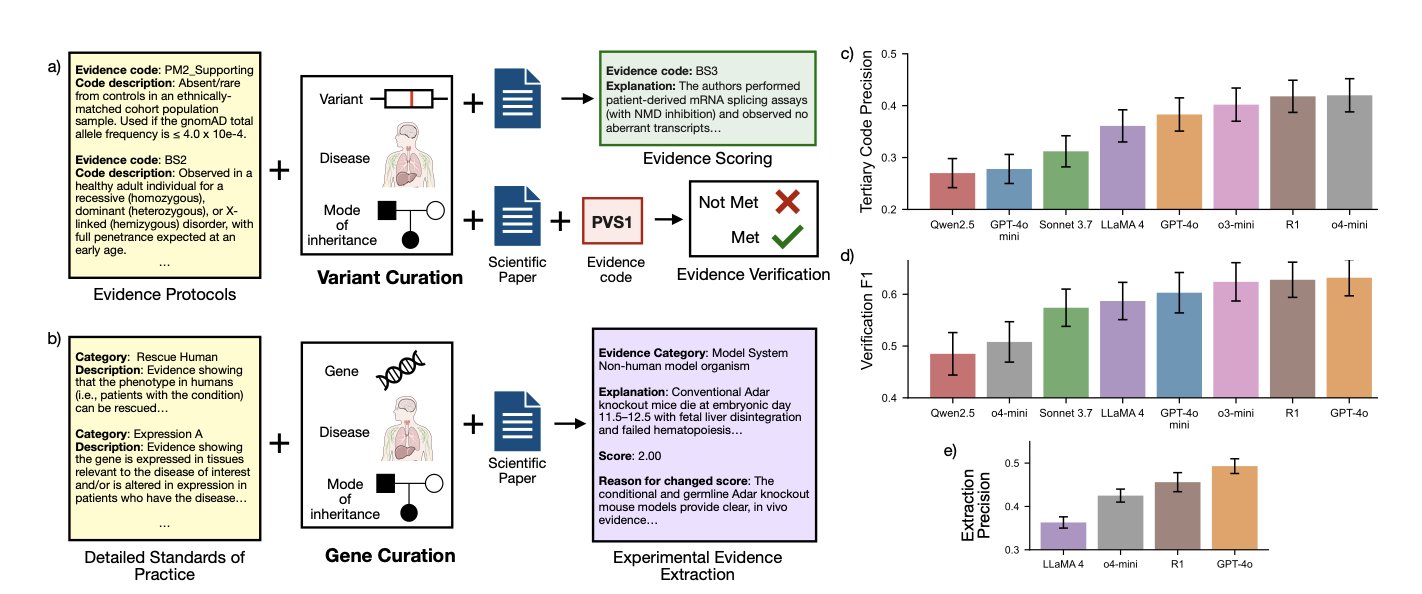

Interpreting newly discovered gene mutations is a core part of genetics research and clinical diagnosis. It’s also time-consuming and difficult. Researchers must search through vast amounts of literature for experimental evidence, then piece together scattered clues to determine if a mutation is benign or pathogenic. This process relies on expert experience and is very slow.

So, people are looking to Large Language Models (LLMs) to take on this work.

The new CGBENCH benchmark was created to assess how well LLMs perform this task. It’s designed specifically for interpreting clinical genetics literature, unlike general question-answering evaluations. This is a major test of an AI’s scientific reasoning ability in a specialized and life-critical field.

The benchmark’s data comes from ClinGen, a genetics literature database manually curated and interpreted by experts. The test is structured around the expert workflow and includes three core tasks:

- Evidence Extraction: Accurately identifying relevant experimental results from a paper.

- Evidence Verification: Given a conclusion, asking the model if there is evidence in the paper that supports or refutes it.

- Evidence Scoring: The hardest and most critical step. The model needs to judge the “strength” of a piece of experimental evidence—is it strong proof or a weak correlation?

The research team tested eight major LLMs. The results showed that while the models performed acceptably on direct tasks like information extraction, they failed almost completely on “evidence scoring,” which requires deep understanding and judgment. They struggled to distinguish between strong and weak evidence.

This is a fatal flaw in a clinical setting. If a model misjudges a weak in-vitro experiment as conclusive proof of a disease link, it could lead to a serious misdiagnosis.

CGBENCH’s evaluation method revealed a deeper problem. The team used a “LM-as-a-judge” strategy, comparing model-generated explanations with expert explanations. They found that even when a model gave the correct classification (like “supports” or “refutes”), its explanation was often fabricated—a “hallucination.”

It’s like a student guessing the right answer but having a completely wrong method for solving the problem. In rigorous scientific research and clinical applications, a tool with an unreliable process cannot be used.

CGBENCH is a sober reminder and a pointer to the future. It shows that current LLMs have a long way to go before they can be reliable research assistants. What models need to improve is not just information retrieval, but rigorous, detailed, and trustworthy scientific reasoning. This benchmark provides a clear target for future model development.

📜Title: CGBENCH: Benchmarking Language Model Scientific Reasoning for Clinical Genetics Research 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.11985

2. DemoDiff: Teaching AI to Design Molecules with a Few Examples

Drug discovery often presents a common challenge: you have a few molecules with good activity, but they have poor solubility or metabolic stability. The task is to optimize their structure, but with only a handful of data points, most machine learning models are useless.

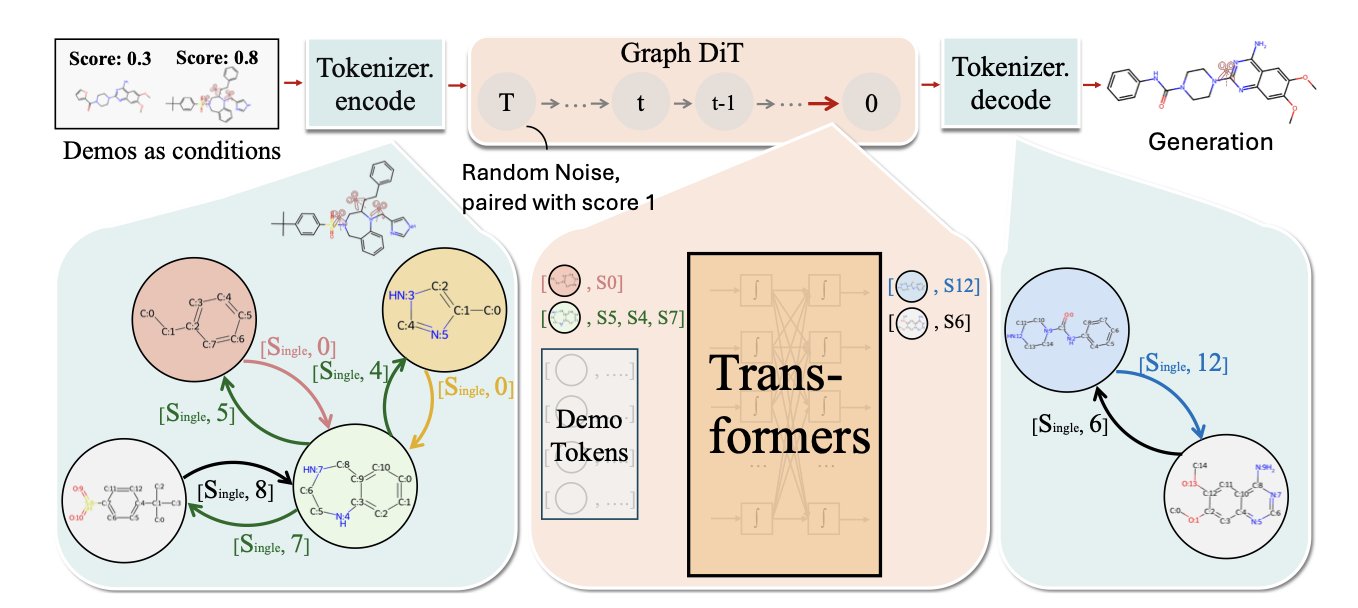

The DemoDiff model was designed to solve this kind of problem.

Its core method is in-context learning. You can show the model a few examples, like a high-activity molecule (a positive example) and a low-activity one (a negative example), and then ask it to design a better one. This interaction is much closer to a chemist’s workflow and doesn’t rely on thousands of labeled data points.

To make this work, the key is how the model “reads” molecules.

DemoDiff uses a new method called Node Pair Encoding (NPE) to break down molecules into chemically meaningful “motifs” or “functional groups,” like benzene rings or carboxyl groups.

This is like upgrading the machine from reading letters to reading words, which is closer to how chemists reason based on functional groups. This approach reduces the number of nodes in the molecular representation by 5.5 times, greatly improving computational efficiency and making it possible to pre-train on massive molecular datasets.

The model is first pre-trained on a dataset containing millions of molecules to learn general chemical principles. Then, for a specific task, the few examples we provide become the context that guides the model to understand the specific design requirements.

Researchers tested DemoDiff on 33 molecular design tasks across 6 major categories. Its performance not only surpassed other models designed for specific domains but also exceeded that of Large Language Models with 100 to 1,000 times more parameters. This shows that a refined architecture tailored for chemistry is more effective than a general model that just relies on more computing power.

Generative models can sometimes produce molecules that look plausible but are actually ineffective. To address this, the researchers introduced a “consistency score.” This score measures the model’s “confidence” in its generated results, helping us filter out potential false positives. This is crucial for practical applications.

DemoDiff demonstrates a new paradigm for molecular design. It allows AI to learn and reason quickly from a few examples, much like an experienced chemist, freeing us from the dependence on massive labeled datasets. This approach is powerful and makes AI tools more practical and reliable.

📜Title: Graph Diffusion Transformers Are In-Context Molecular Designers 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.08744

3. LLM + Knowledge Graph: The LLaDR Framework Reshapes Drug Repurposing

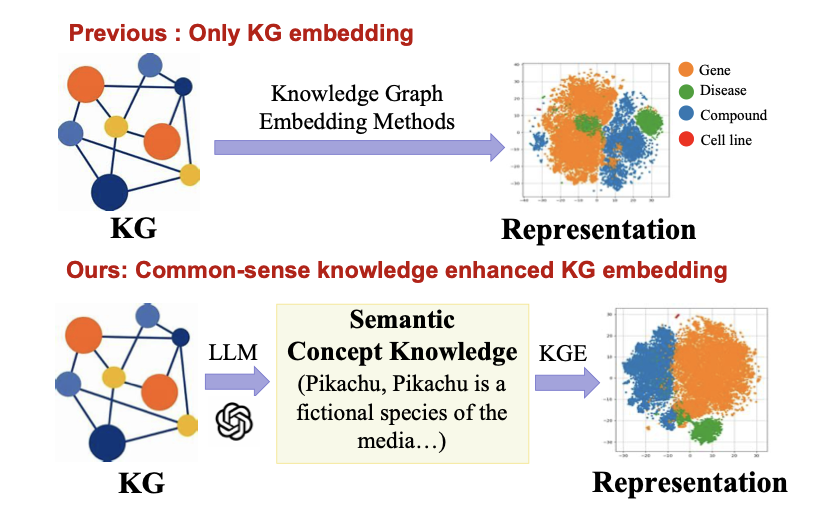

In drug development, drug repurposing is a strategy to find new uses for existing drugs, which saves time and money. Traditional methods often use biomedical Knowledge Graphs (KGs), which are like giant networks connecting drugs, genes, and diseases. But these networks only know about the connections between entities; they don’t understand the reasons behind those connections. A KG knows drug A is related to protein B, but it doesn’t know if A inhibits or activates B, let alone the biological mechanism involved.

The idea behind the LLaDR framework is simple: if the knowledge graph lacks biological “common sense,” let a knowledgeable teacher teach it. This teacher is a Large Language Model (LLM). LLMs have read vast amounts of scientific literature and have a much deeper understanding of biomedical concepts than a simple node in a knowledge graph.

Here’s how it works:

First, the researchers extract entities from the knowledge graph, like drugs, targets, or diseases. Then, they have the LLM generate a description for each entity, including its function, mechanism of action, and relevant background. This is like giving a detailed profile to a node in the knowledge graph that previously only had a name.

After getting these “profiles,” the key step is to use this semantically rich text to fine-tune the mathematical representation—the embeddings—of the corresponding nodes in the knowledge graph. The original embeddings of a knowledge graph are like a rough sketch. After being fine-tuned with knowledge from the LLM, they become a rich, full-color photograph. This “photograph” not only depicts the node itself but also includes its role and behavior within the entire biological network.

The benefit of this approach is that the “educated” knowledge graph can reason based on biological logic when predicting new uses for drugs, rather than just matching graph structures. The paper shows that LLaDR outperforms existing methods on standard test sets and is more stable when dealing with noisy or incomplete data. This is valuable in real-world applications, as biological data is often imperfect.

A telling example: Alzheimer’s disease

The researchers applied LLaDR to drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease. Without any preconceived bias, the model identified several potential candidate drugs, including Dasatinib and Quercetin.

For researchers in the field, these two names are familiar. Dasatinib is an approved anti-cancer drug that recent studies have found can clear senescent cells, a new strategy for treating neurodegenerative diseases. Quercetin is a natural flavonoid with extensive literature supporting its neuroprotective effects. The model’s ability to independently identify these research directions that the scientific community is already exploring proves its effectiveness. It shows that LLaDR found a signal with a real biological basis.

How do we, as frontline R&D personnel, see this?

This method has great potential, but it also faces challenges. First, it depends on the quality of the LLM’s knowledge. If the LLM’s training data is biased or outdated, it might teach the knowledge graph incorrect or obsolete information. Second is the computational cost. Fine-tuning a large-scale knowledge graph with millions or even billions of connections is expensive, and implementing it in production is a challenge. Finally, there’s explainability. The model recommended Dasatinib, but can it tell us “why”? Can it output a complete, experimentally verifiable hypothesis of a biological pathway? This is a core problem for all AI drug discovery tools. LLaDR brings us a step closer to the answer, but the journey isn’t over.

Overall, LLaDR’s work points to a clear direction: combining the unstructured knowledge of LLMs with the structured data of knowledge graphs can create more powerful drug discovery engines. It allows machines to “think” about biological problems in a way that is closer to how human scientists think.

📜Title: From Knowledge to Treatment: Large Language Model Assisted Biomedical Concept Representation for Drug Repurposing 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.12181