Contents

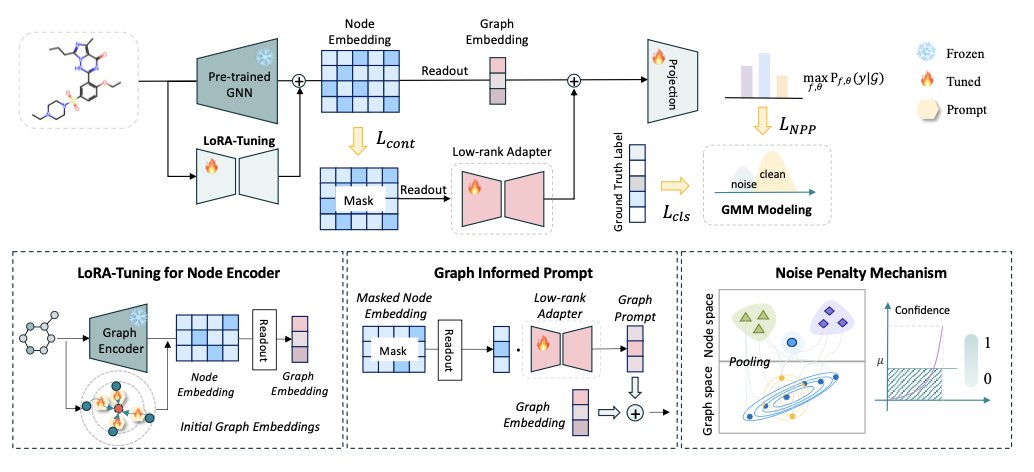

- The GraphBFN framework combines hierarchical modeling and Bayesian Flow Networks, offering a new way to handle discrete data in molecular graph generation for designing better molecules faster.

- A large-scale experiment reveals that finding a protein binder depends mainly on the target’s intrinsic properties, not the screening method, providing new ideas for drug design.

- The MIPT framework uses a set of lightweight, multi-level prompts to let pre-trained graph neural networks accurately and efficiently adapt to specific molecular property prediction tasks.

1. GraphBFN: A New and Better Way for AI to Make Molecules

A key goal in drug discovery is to design new molecules with a computer. Diffusion models from image generation have gotten a lot of attention recently, and many have tried using them to generate molecules. But molecules are graph structures made of discrete atoms and bonds, while images are continuous grids of pixels. Applying image generation models directly is like trying to build with Lego bricks using watercolor techniques—it just doesn’t fit.

Most diffusion models treat discrete atom and bond types as continuous variables during generation, then round them off at the end. This approach is not mathematically sound and often produces molecules with invalid chemical structures. It can also require many “denoising” steps to get a usable result, which is inefficient.

GraphBFN offers a new approach.

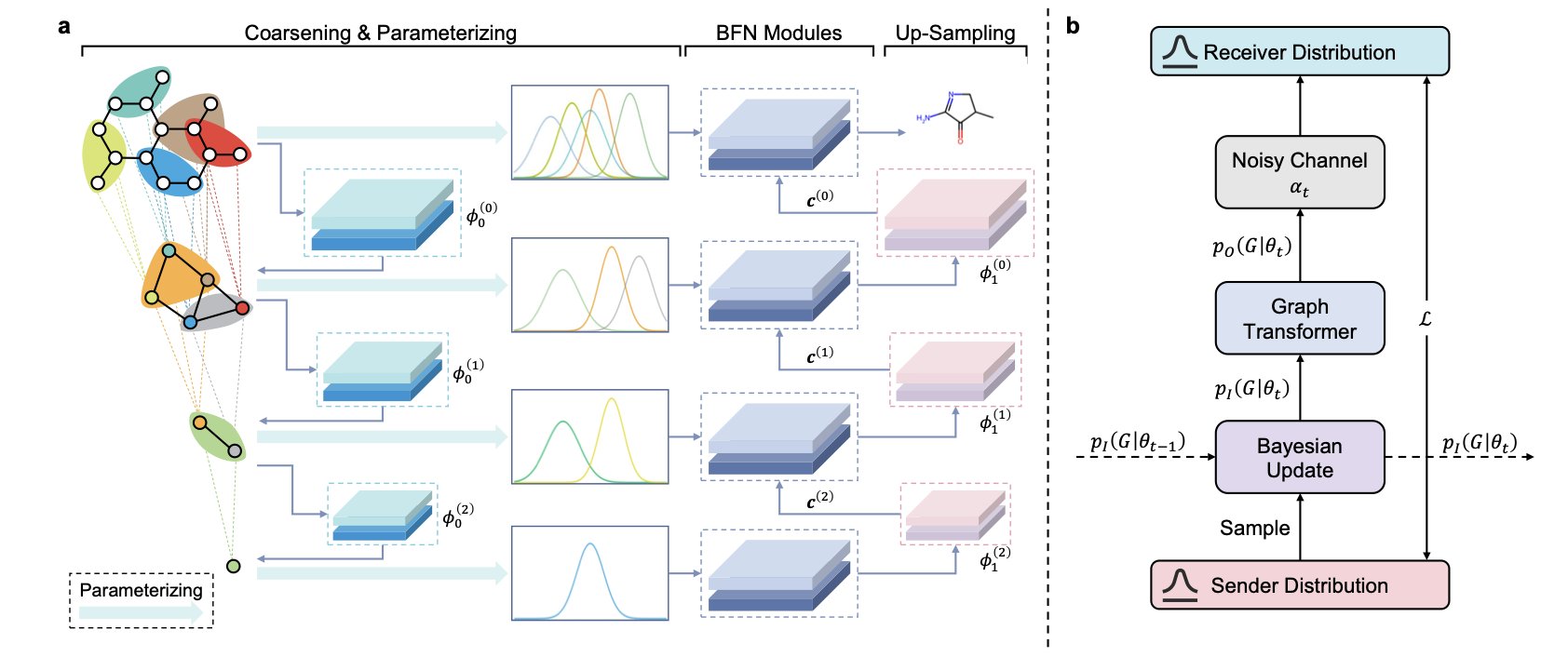

It uses Bayesian Flow Networks (BFNs). The core idea of a BFN is to learn a mapping from simple noise to a complex molecular structure. Its theoretical framework naturally handles discrete data, unifying the training objective and the sampling process. The model therefore infers atom types within a probabilistic framework.

The model also introduces a “coarse-to-fine” hierarchical generation scheme. An experienced chemist designing a molecule first thinks about the core scaffold, then adds details like substituents.

GraphBFN works similarly. It uses a technique called graph coarsening to simplify a complex molecular graph into a few “supernodes,” capturing the molecule’s overall topology. The model first generates this coarse framework and then refines it step-by-step, filling in the specific atoms and bonds. This global-to-local generation process ensures the molecular scaffold is chemically sound and reduces the chance of creating invalid structures, like high-strain small rings.

To improve efficiency and accuracy, the model calculates probabilities for atom types using a Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF). Unlike methods that directly fit the probability value for each atom type, fitting the cumulative probability is more stable for categorical data and helps the model converge faster.

On two standard datasets, QM9 and ZINC250k, GraphBFN performs very well. The molecules it generates are top-tier in terms of validity, novelty, and uniqueness, and it reaches this quality with fewer sampling steps. In drug discovery, this allows researchers to explore a larger chemical space with less computational cost and in less time, which is a big advantage for high-throughput virtual screening.

Challenges remain. The current work focuses on small molecules. The next step is to see if the framework can be extended to more complex macromolecules like macrocycles, peptides, and proteins. Also, enabling conditional generation—for example, requiring a molecule to have specific pharmacokinetic properties or target affinity—is critical for its practical application.

📜Title: Hierarchical Bayesian Flow Networks for Molecular Graph Generation

🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.10211v1

2. The Protein Binding Puzzle: Why Are Some Targets So Hard to Drug?

In drug development, especially for biologics like antibodies or peptides, a common problem arises: why do some targets yield no good hits after repeated screening, while others are very fruitful? We used to blame bad luck or the design of the screening library. But the root of the problem might lie with the target itself.

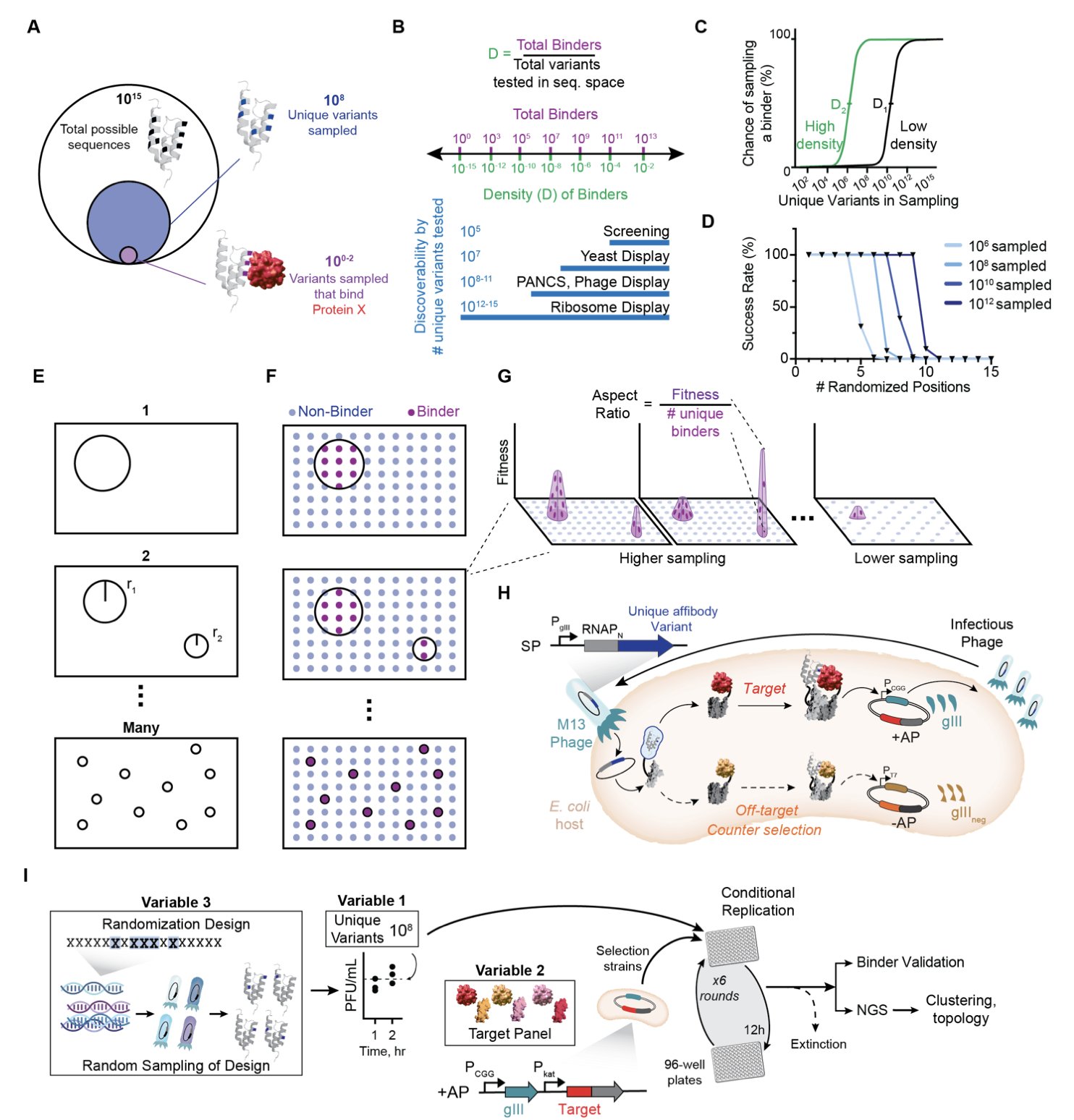

A recent preprint on bioRxiv systematically answers this question. Researchers used a high-throughput technique called PANCS-Binder to screen 96 different protein targets at once, trying to find new protein sequences that could bind to them.

The study’s most striking finding is that the difficulty of finding a binder varies enormously from one target to another.

It’s like panning for gold on a beach. Some targets are like rich deposits, where one in every 100,000 random sequences will bind. Others are like searching for a single grain of gold in a whole desert, where you might find only one hit in 10 billion sequences. The difference in difficulty is a factor of over 100 million.

This difference is mainly determined by the intrinsic properties of the target protein, with little influence from the design of the screening library. Some targets are just set to “hard mode” from the start, and no matter how cleverly the library is designed, the success rate is low.

Using this high-quality data of positive and negative samples (thousands of binding sequences versus hundreds of thousands of non-binding ones), the researchers trained a machine learning model to predict whether a new sequence could bind to a target. The model generalized well to unseen datasets, accurately identifying binders.

This provides a new tool for Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD). We can now use models trained on real experimental data to evaluate the success rate of virtual designs, or even predict the difficulty of developing a new target before experiments begin.

The researchers propose the concept of “minimal binding motifs,” analogous to the key pins needed to open a lock. If a lock needs only two or three key pins, many keys will work. If it needs seven or eight to align perfectly, very few keys will open it. The number of key pins is inversely proportional to the density of binders, thus quantifying the druggability of a target.

This work uses large-scale, systematic experimental data to reveal the underlying principles of finding protein binders. When green-lighting a project, we should evaluate a target’s “binding friendliness” in addition to its biological significance. This high-quality dataset is also a valuable resource for training more powerful AI design models, making drug discovery less about guesswork and more about science.

📜Title: Mapping the Diverse Topologies of Protein-Protein Interaction Fitness Landscapes

🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.14.682342v2

💻Code: