Table of Contents

- The SAM-DTI model first builds a 2D interaction map of drug-protein substructures and then uses a spatial attention mechanism to focus on key regions, achieving more accurate and chemically intuitive drug-target interaction predictions.

- Using molecular docking scores as features can improve the data efficiency and hit rate of machine learning in drug optimization.

- Ensemblify is a computational tool that uses AlphaFold’s low-confidence scores as a guide to efficiently generate dynamic conformational ensembles of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), solving a major challenge in structural biology.

- FusionCLM combines the strengths of multiple chemical language models using a stacked ensemble learning strategy, providing a more accurate solution for molecular property prediction.

- A new method using unbiased random sampling allows us to generate truly representative molecular datasets, fundamentally addressing the data bias problem in current AI drug discovery models.

1. SAM-DTI: A New AI Model to Rethink Drug-Target Prediction

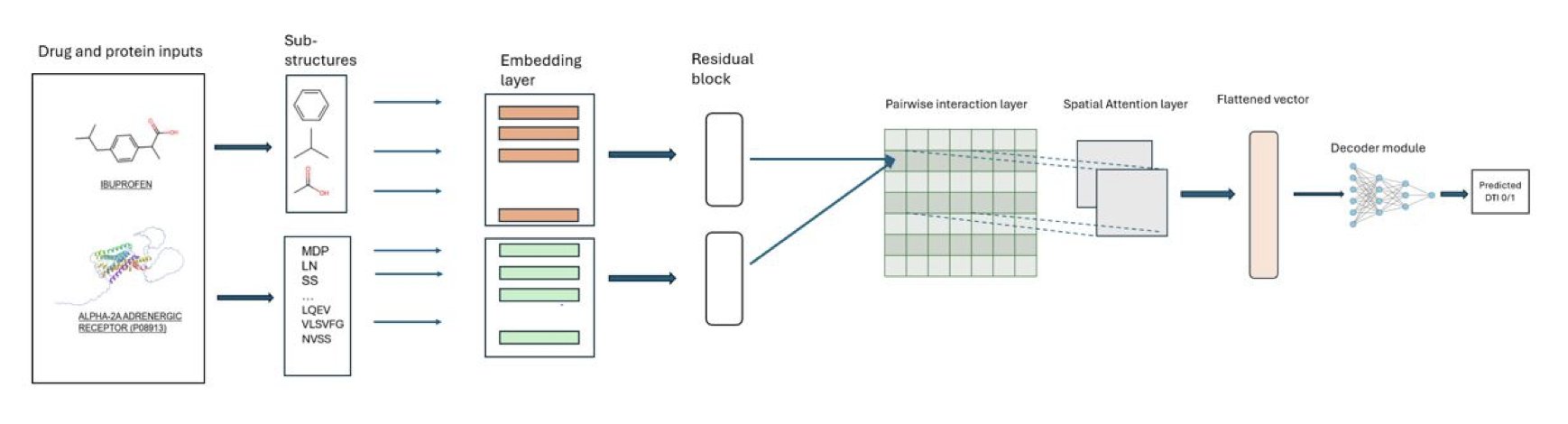

There are many AI models for predicting Drug-Target Interactions (DTI), but most of them work in a roundabout way. They typically take a drug molecule (like a SMILES string) and a protein sequence (like a FASTA sequence), feed each into a separate encoder to extract features, and only merge these two streams of information at the very last step to decide if they bind.

This is like trying to figure out if a key fits a lock by only studying the key’s material and the lock’s brand, instead of just seeing if the key’s teeth match the lock’s pins. This “late fusion” strategy loses the most critical spatial correspondence between the two early in the process.

The SAM-DTI model takes a more direct approach.

Instead of letting the drug and protein information go their separate ways, the researchers bring them together from the start. They first break down both the drug molecule and the protein into chemically or biologically meaningful “substructure” units. Then, they build a two-dimensional interaction matrix. You can think of this matrix as a chessboard. The horizontal axis represents the drug’s substructures, and the vertical axis represents the protein’s substructures. Each square on the board represents a potential interaction between a specific pair of substructures.

This turns a complex DTI prediction problem into a more intuitive image recognition problem.

Next comes the model’s core component: a spatial attention mechanism. With this “interaction chessboard,” the model scans the entire map like an experienced chemist. Its attention naturally focuses on the key “hotspots” that determine binding. For example, the “square” formed by a hydrogen bond donor on the drug and a hydrogen bond acceptor in the protein’s pocket would be given a higher weight.

The benefits of this method are obvious. It aligns better with our chemical intuition about molecular recognition, and because the model “sees” the global interaction pattern, its predictions are more accurate. The data shows that SAM-DTI outperforms several existing baseline models on multiple public datasets (measured by ROC-AUC and PR-AUC). This means it performs more reliably when screening for true positive results.

A model’s value is ultimately judged by its ability to solve real problems. The researchers used SAM-DTI for virtual screening in drug repurposing and found some interesting results. For instance, the model predicted that the natural products curcumin, EGCG, and melatonin might act on new targets. These are valuable scientific hypotheses that can be validated by future experiments.

The paper’s ablation study also confirmed the soundness of the model’s design. The results showed that the spatial attention mechanism is the core driver of performance improvement, while other components like residual connections play a supporting role, helping to further optimize the model.

Overall, SAM-DTI shifts the design philosophy from “sequence processing” to “spatial relationship modeling,” bringing AI a step closer to how chemists think about molecular interactions.

📜Title: SAM-DTI: A Spatial Attention Model for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.31.673317v1

2. A New Idea in AI Drug Discovery: Empowering Machine Learning with Docking Scores

In the early stages of drug discovery, we are always playing a numbers game. The scale of chemical space is astronomical, while our time and budget are limited. We have two main tools for molecular screening: Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) and Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS).

SBVS is like trying a key (a small molecule) in a lock (a target protein). Docking is its core technique, using physics-based models to predict how a molecule binds to a target and with what affinity. This method is intuitive, but the accuracy of docking scores can sometimes be disappointing.

LBVS is different. It doesn’t look at the shape of the “lock” but analyzes all the “keys” that are known to open it. Through machine learning, a model can learn chemical patterns from known active molecules and then predict the activity of new ones. This approach is powerful when there’s enough data, but if you have very little data to start with, the model has nothing to learn from.

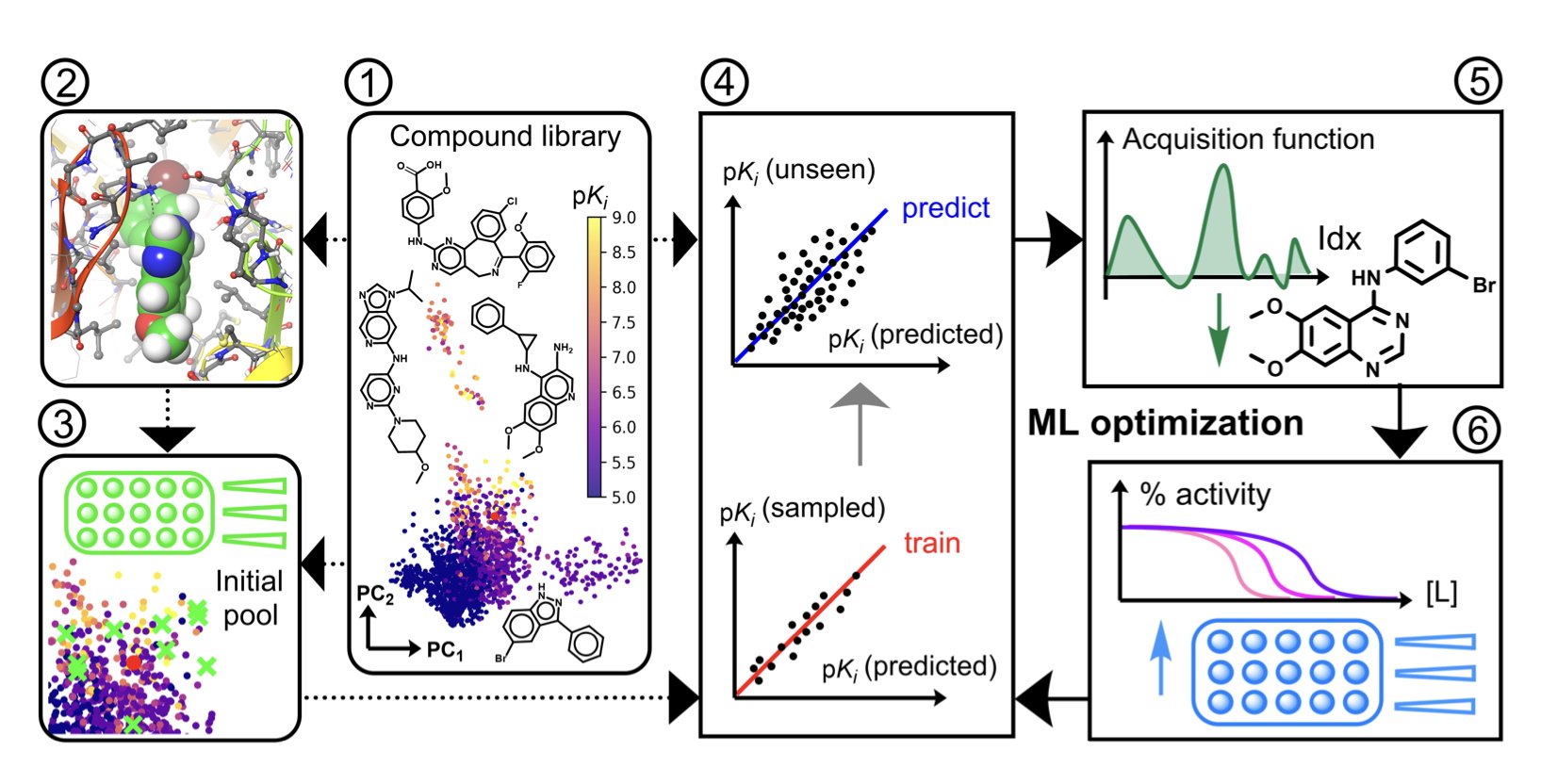

The researchers behind this paper tried to combine the strengths of both.

Their idea was to let the physics-based model give the machine learning model some “initial hints.” Specifically, they first docked all the molecules in a library against the target to get a docking score. Then, they fed this score as an additional feature to the machine learning model.

This process uses a Bayesian optimization framework. You can think of Bayesian optimization as a treasure-hunting robot. Each time it digs, it updates its treasure map based on what it finds and then decides where to dig next. The traditional approach is to let the robot start digging randomly.

The researchers’ improvement was to give the robot a “rough treasure map” first, using the docking scores. They used the molecules with the best docking scores as starting points, telling the robot to begin digging in the places most likely to hold treasure.

The results showed that on 14 ChEMBL datasets and 4 challenging LIT-PCBA datasets, this “docking-informed” method performed well. Compared to traditional random or diversity-based initialization, it reduced the average number of compounds that needed to be tested to find the optimal active molecule by 24%. In virtual screening, its ability to find highly active molecules (enrichment factor) increased by 32%.

Fewer experiments mean lower costs. In drug development, every compound you don’t have to synthesize and test saves valuable time and money.

The value of this strategy lies in its practicality. It doesn’t invent a new, complex algorithm but cleverly combines two mature tools to achieve a result where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

This approach offers a great starting point, especially for new target projects that lack initial activity data. It leverages physical information—the target’s structure—to guide the data-driven machine learning model, preventing it from fumbling in the dark at the outset.

📜Title: Optimizing Drug Activity Using Docking-Informed Machine Learning 📜Paper: https://chemrxiv.org/engage/api-gateway/chemrxiv/assets/orp/resource/item/68b6f727a94eede1541ec4da/original/optimizing-drug-activity-using-docking-informed-machine-learning.pdf

3. Ensemblify: Turning AlphaFold’s Uncertainty into a Treasure Trove for IDP Conformation Sampling

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) are a tough problem in drug development. They lack a fixed 3D structure yet play roles in key biological processes like signal transduction and cell cycle regulation, making them potential targets for many diseases. Their highly dynamic nature makes them difficult to address with traditional drug discovery methods.

AlphaFold excels at predicting stable, folded domains, but it produces low pLDDT confidence scores when it encounters IDPs or the flexible linkers connecting domains. In the past, researchers usually ignored these low-score regions.

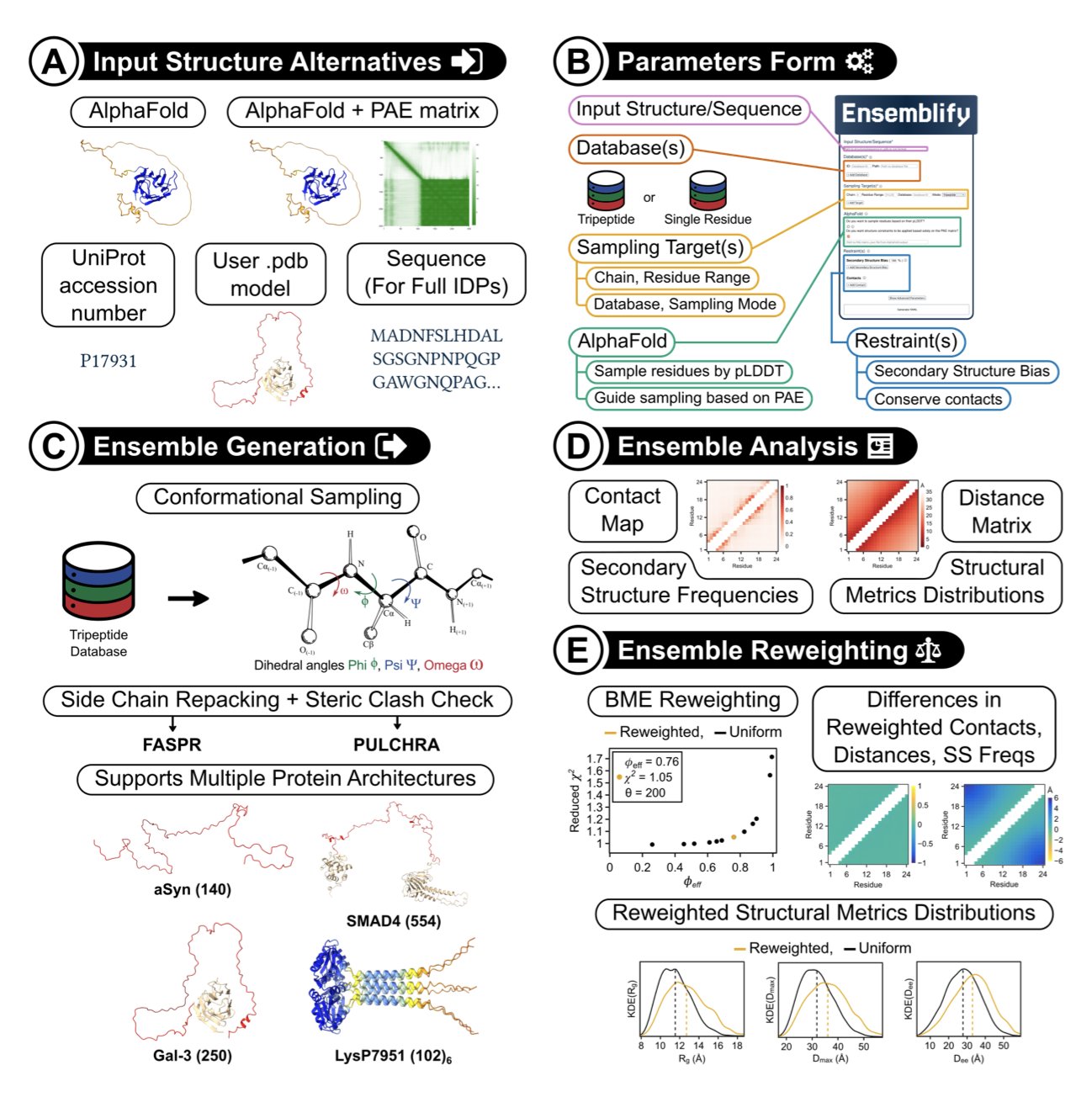

The Ensemblify tool offers a new way of thinking: use AlphaFold’s uncertainty as a form of information.

Here’s how it works:

First, it takes an AlphaFold prediction for a protein. For stable regions with high pLDDT scores, it locks the structure in place.

Then, for the Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) with low pLDDT scores, it uses a Monte Carlo algorithm to perform extensive conformational sampling, rapidly exploring the various shapes they might take.

The most critical step is that Ensemblify incorporates AlphaFold’s pLDDT and PAE scores as “flexible restraints” into the PyRosetta energy function. Regions where AlphaFold is less confident are allowed greater conformational freedom, while regions with slightly higher confidence are more constrained. It interprets AlphaFold’s “uncertainty” as “physical flexibility.”

In this way, Ensemblify can efficiently generate an “ensemble” containing thousands of conformations. This ensemble provides a more realistic picture of an IDP’s dynamic behavior under physiological conditions than a single static structure.

A drug molecule might only bind to a specific conformation of an IDP. With only a static structure, we might miss this druggable “transient state.” With a conformational ensemble, researchers have a chance to screen for key conformations and design drugs based on them.

The researchers tested Ensemblify on 10 different proteins. The results showed that the generated conformational ensembles agreed well with experimental data from techniques like Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS), proving the tool’s utility.

Ensemblify offers a command-line interface and a simple HTML parameter form, making it easy to use. Biologists without a strong background in computational chemistry can get started quickly, which should speed up research into IDP function and druggability.

Ensemblify turns a model’s “weakness” into a useful input for problem-solving, providing a new key to explore the challenging field of IDPs.

📜Title: Ensemblify: a user-friendly tool for generating ensembles of intrinsically disordered regions of AlphaFold and user-defined models 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.26.672300v1

4. FusionCLM: A New Paradigm in AI Drug Discovery by Fusing Language Models

In drug discovery, we are always searching for better computational models to predict molecular properties. There are now several Chemical Language Models (CLMs) that treat molecular structures (usually SMILES strings) like a language. Examples like ChemBERTa and MolT5 each act like specialists with their own expertise. When faced with a new molecule, deciding which “expert” to listen to becomes a challenge.

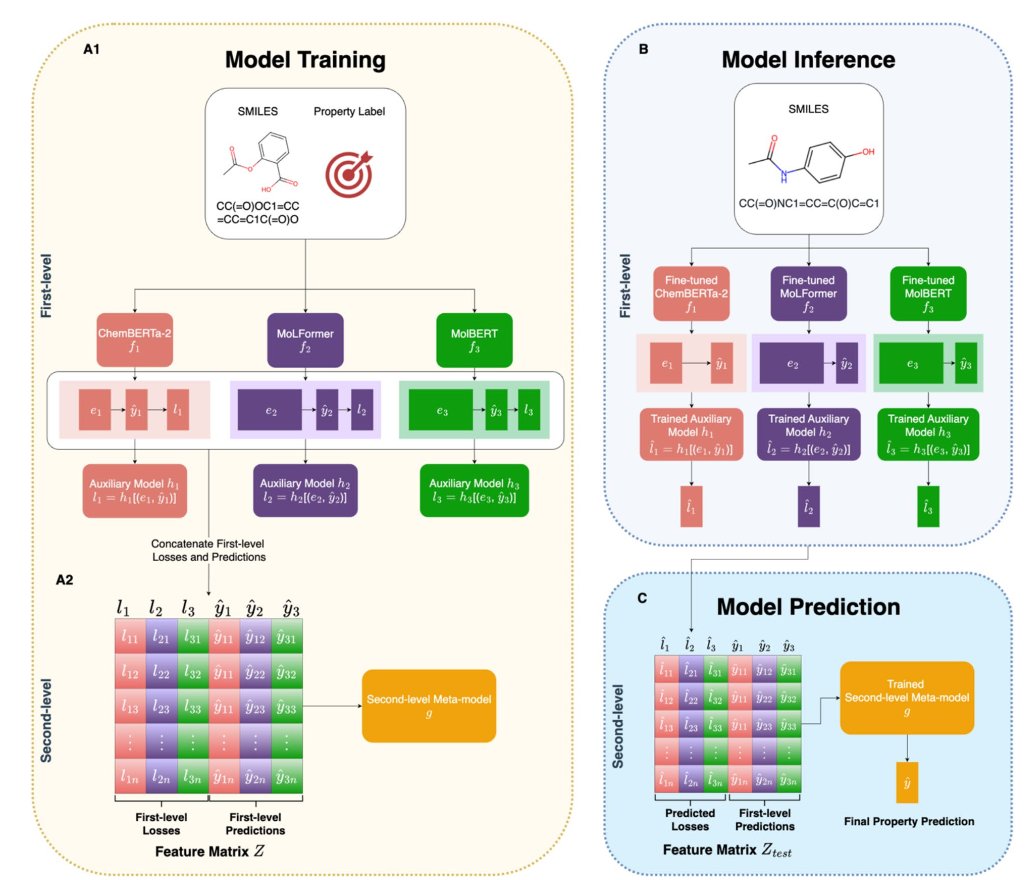

The traditional approach is to pick the best-performing model or simply average the opinions of all the experts. But this method ignores how “confident” each expert is about different problems. The FusionCLM paper proposes a more refined solution, like assembling an effective expert committee rather than just taking a simple vote.

Here is how it works.

The process has two steps. In the first step, a molecule is presented to all the “experts” (the individual CLMs) on the committee. Each expert provides three things: 1. A prediction: For example, the molecule’s solubility. 2. A SMILES embedding: The expert’s “understanding” of the molecule, a numerical vector containing chemical information. 3. A predicted loss: This can be seen as the expert’s “lack of confidence” in its own prediction.

The key here is the third point. The researchers designed an auxiliary model specifically to “estimate” the error each expert is likely to make on a new task (the test loss). This is like asking each expert to provide a self-assessment along with their opinion: “For this type of molecule, my judgment is about 80% accurate.”

Next is the second step. FusionCLM bundles together all the experts’ “predictions,” their “lack of confidence” (estimated loss), and their “understanding” (SMILES embeddings) to form a more comprehensive feature matrix.

This enhanced feature matrix is then submitted to a “committee chair” (a meta-model, such as XGBoost). The “chair’s” job is to learn how to make the final, most reliable decision based on each expert’s opinion and their confidence level. If the “chair” finds that expert A is consistently less confident when dealing with macrocycles (high predicted loss), it will reduce expert A’s influence in the final decision.

This method is effective because it doesn’t just perform a simple weighted average; it dynamically learns which model to trust under which circumstances. Adding the SMILES embeddings is like allowing the “chair” to not only hear the conclusion but also understand each expert’s “thought process” in reaching it, providing richer context for the final decision.

The researchers tested FusionCLM on five standard datasets from MoleculeNet. The results showed that this “expert committee” outperformed any single expert and also surpassed some other advanced multi-modal deep learning frameworks.

FusionCLM’s appeal lies in its practicality. We don’t need to train a massive new model from scratch. Instead, we can leverage existing, pre-trained CLMs and unlock more of their potential through this ensemble approach. The workflow is still somewhat complex, and future work to simplify it and improve its interpretability—for instance, by helping us understand the “committee chair’s” decision-making process—would make it even more valuable.

📜Title: FusionCLM: enhanced molecular property prediction via knowledge fusion of chemical language models 📜Paper: https://jcheminf.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13321-025-01073-6 code: https://github.com/Yutong-Lu/FusionCLM

5. A New Sampling Method for Chemical Space: Can AI Drug Discovery Move Beyond Data Bias?

In computational chemistry and drug discovery, almost all of us rely on existing chemical databases like QM9 or the GDB series. We use this data to train machine learning models, hoping they can predict the properties of new molecules. But these databases are biased. They are like maps that only show the roads we have already traveled, leaving vast, unknown territories blank. The models we train are more like drivers familiar with specific city routes than explorers who can navigate uncharted continents.

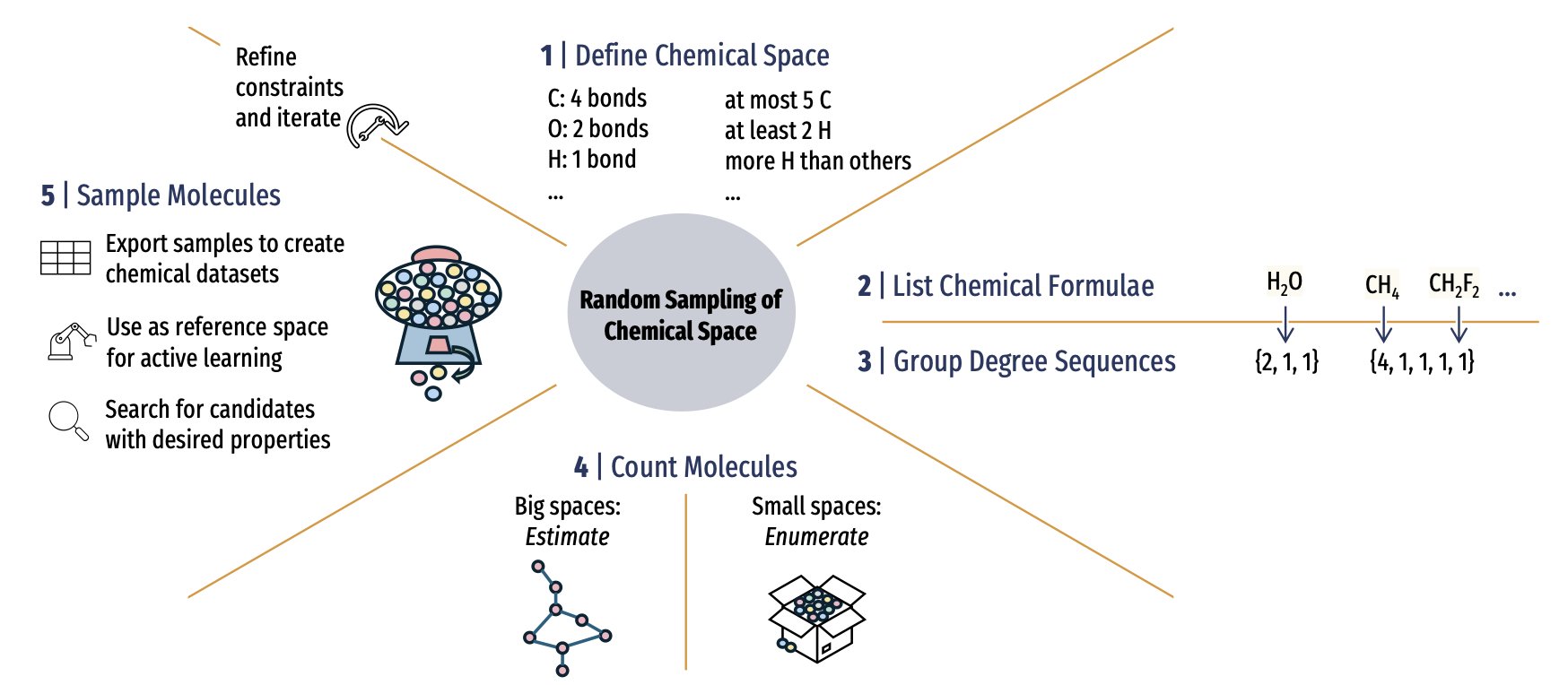

A new paper proposes a solution that gives us a chance to draw a more complete map of chemical space.

Escaping the “Streetlight Effect”

The scale of chemical space is beyond imagination. Even when limited to a few elements and a few dozen atoms, the number of possible molecular structures is astronomical. Our existing databases, whether from experimental synthesis or theoretical calculations, represent just a tiny fraction of this vast universe. This bias is known as the “streetlight effect”—we always look for our keys (useful molecules) under the streetlight (in the known, easy-to-synthesize parts of chemical space) because that’s where it’s brightest.

The work in this paper is about developing a method for unbiased random sampling of any user-defined chemical space. This means we can finally know what percentage of the chemical space a database like GDB-13 actually represents and how biased it is. According to their analysis, the representativeness of existing databases is not ideal.

How does it work?

The method’s core has two steps.

First, it uses a mathematical technique called “integer partitioning.” Imagine you want to build a molecule with carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms, with a total of no more than 30 atoms. Integer partitioning helps list all possible combinations of atoms—that is, all possible molecular formulas. This breaks down a complex problem into a series of well-defined smaller ones.

Second, for each specific molecular formula, it employs Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. You can think of MCMC as a “random walker.” You place it in the space of all possible isomers for a given formula, and it wanders around, with each step following specific probability rules. After walking long enough, the samples it collects can accurately represent the overall distribution of that space. This process doesn’t require us to list all possible isomers beforehand, which greatly improves efficiency.

This approach allows us to “fish out” molecular samples from the entire chemical space fairly and without bias.

What does this mean for AI drug discovery?

This is crucial for how we train machine learning models. A model trained on a biased dataset will have limited generalization ability. When it encounters a new molecule from an “unknown chemical space,” its prediction is likely to be inaccurate.

With this unbiased sampling method, we can build more diverse and representative training sets. Models trained on such data can truly learn the underlying chemical and physical principles, rather than just memorizing patterns of specific molecules. This means the models’ predictions will be more robust and better suited for discovering drug molecules with entirely new scaffolds.

Of course, this method has so far been validated mainly on small molecules with up to 30 atoms. The next challenge is to extend it to larger drug-like molecules while keeping computational costs manageable. But this is undoubtedly a key step in the right direction.

📜Title: Representative Random Sampling of Chemical Space 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.20609v1