Table of Contents

- The CAMT5 model mimics how chemists think in terms of “motifs,” generating more accurate molecules from text descriptions with less training data.

- FragAtlas-62M is an open-source chemical language model that can generate a massive library of novel and chemically valid drug fragments, offering starting points for drug development.

- Combining the chemical knowledge of large language models with a molecule’s structural information improves the accuracy of property predictions.

- The Eigen-1 framework improves the accuracy and efficiency of AI for complex scientific reasoning through seamless knowledge retrieval and hierarchical collaboration, much like how real research works.

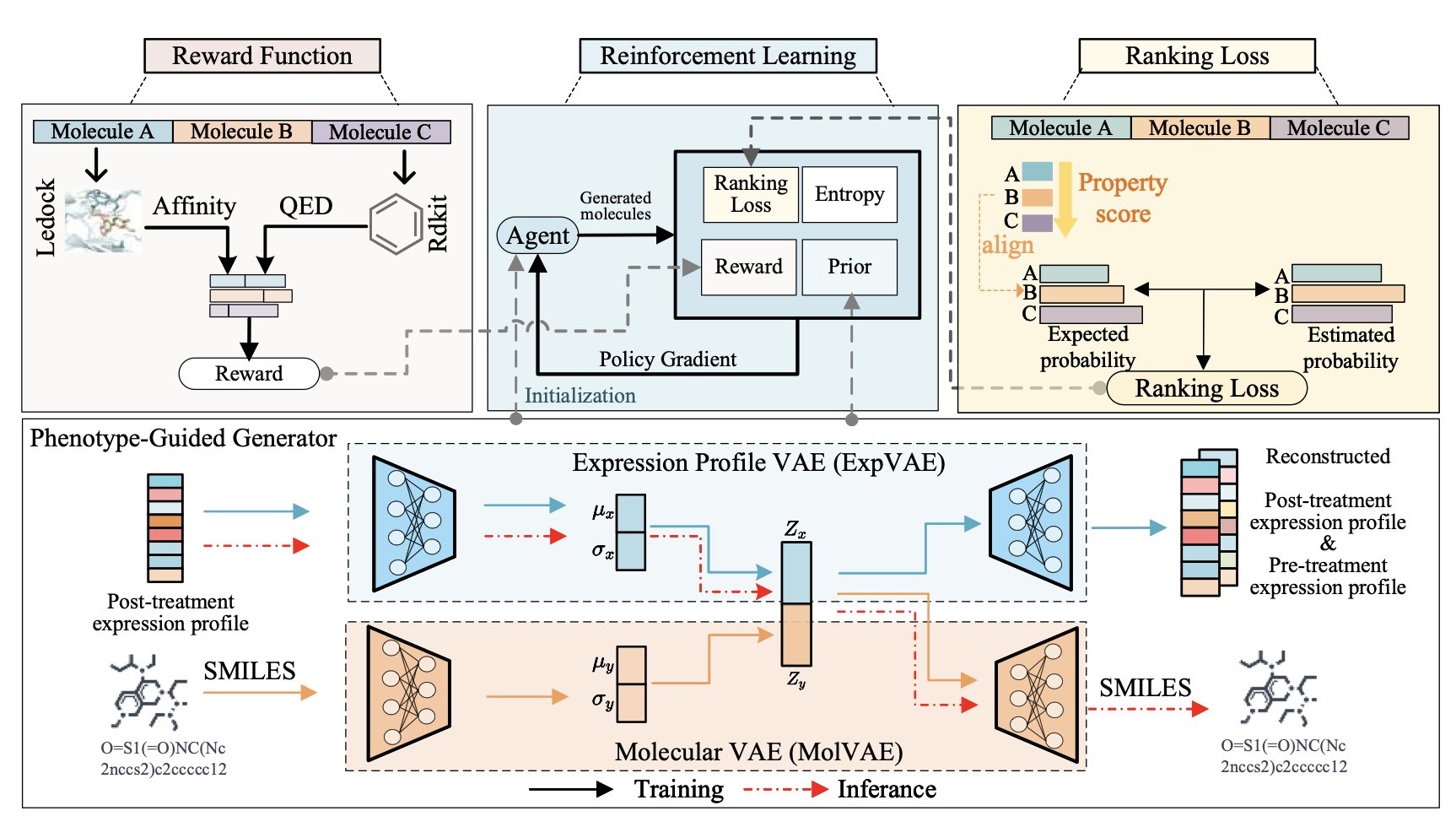

- The ExMolRL framework uses reinforcement learning to combine the results-driven approach of phenotypic screening with the precision of target-based design, generating new molecules that are both bioactive and drug-like.

1. CAMT5’s New Approach: Teaching AI to Build Molecules with a Chemist’s Intuition

In drug discovery, we often have a thought like, “I need a small molecule that selectively targets a specific protein pocket and is also water-soluble.” Turning this kind of natural language description directly into a specific molecular structure is an attractive goal for AI in pharma. But many past models worked like someone trying to assemble chemical structures from an alphabet (C, H, O, N…) without knowing chemistry. The result was often that the grammar (chemical bonds) was correct, but the sentence (the whole molecule) made little chemical sense.

The CAMT5 model from this paper takes a different approach. It’s more like teaching an AI to think in the “jargon” of a chemist.

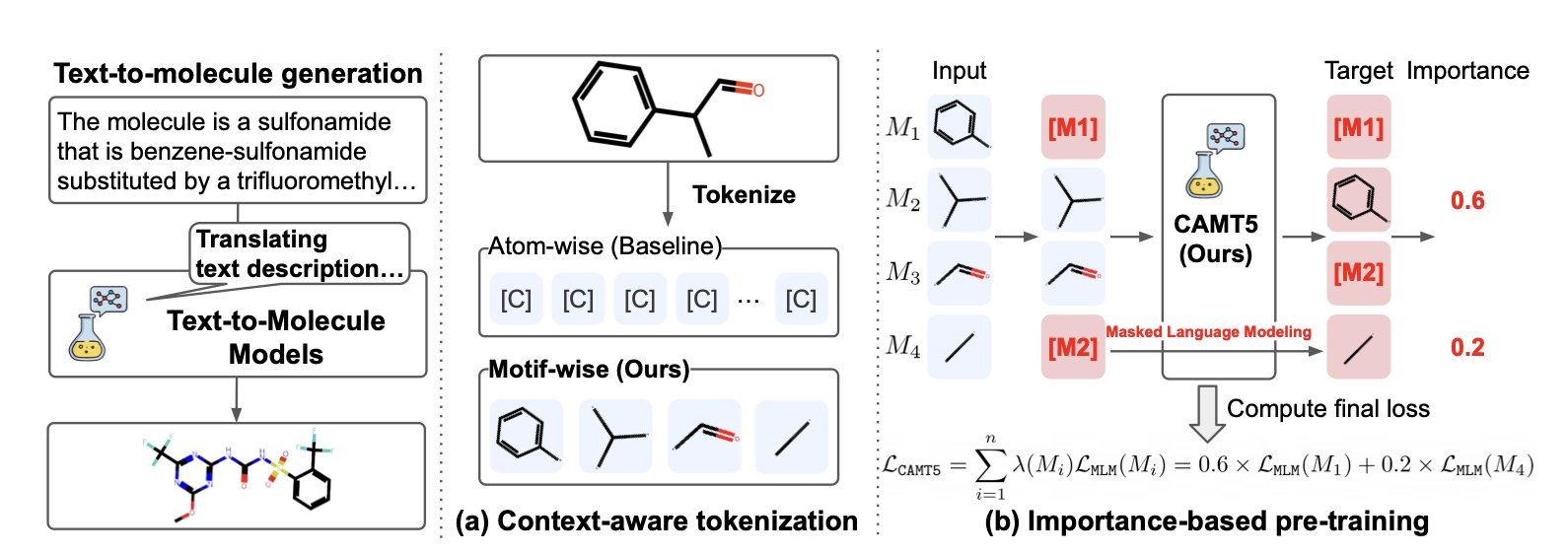

A Mental Leap from “Atoms” to “Motifs”

When a medicinal chemist looks at a molecule, they don’t see a cloud of isolated atoms. They see functional groups: a benzene ring, an amide bond, a piperidine ring. These “motifs” are the smallest units of chemical function and the foundation of how we communicate and think.

CAMT5’s core idea is to teach this way of thinking to an AI. Instead of using atoms as the basic building blocks, it first breaks down thousands of molecules from a library into the common structural fragments and functional groups that chemists recognize. So, the AI learns not just that “a carbon connects to a nitrogen,” but that “this is an amide bond, it usually connects two fragments, and it’s quite stable.”

This motif-based tokenization has a direct benefit: it comes with built-in chemical context. The AI gets a better grasp of the molecule’s overall structure and chemical properties, rather than getting lost in the details of individual atoms.

Helping the AI Focus on What Matters

CAMT5 has another feature called “importance-based pre-training.” In simple terms, during training, the model prioritizes learning the motifs that play key roles in a molecule. For example, a molecule’s pharmacophore or core scaffold is obviously more important than a simple methylene group.

This is like training a new chemist. You’d have them memorize the most critical and common functional group reactions first, not every obscure reaction in the book. It’s a more efficient and effective way to learn.

The results were striking. CAMT5 used only 2% of the training data of the previous best model and still achieved better performance on multiple tasks. This shows that the right learning method is far more important than just throwing more data at the problem. The efficiency gain means lower computational costs and faster iteration, which is crucial for practical applications.

What This Means for Drug R&D

Intuitively, the molecules this model generates have more “chemical sense.” Because they are built from the familiar “building blocks” of chemists, they are more likely to have good drug-like properties and be easier to synthesize.

Of course, the method has its limits. For instance, is its “vocabulary” (the motif library) rich enough to cover truly novel chemical space? What happens when it encounters a completely new scaffold it has never seen before? These are questions for the next steps.

But CAMT5 offers an important insight: teaching AI to think like a domain expert might be the right path toward more powerful and practical tools. It’s not creating from scratch; it’s learning and combining the chemical wisdom that human chemists have accumulated over centuries.

📜Title: Training Text-to-Molecule Models with Context-Aware Tokenization 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.04476

2. FragAtlas-62M: A New Box of Building Blocks for Chemists, or Just an Empty Promise?

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) is like building a model with Legos. Chemists first find small molecular “bricks,” or fragments, that weakly bind to a target protein. Then they link or optimize these fragments to build a potent drug. The strategy has been successful, but finding high-quality initial “bricks” is the first hurdle. Chemical space is vast, and searching it with human intuition and traditional methods is slow.

FragAtlas-62M is a tool designed to make this search for “bricks” smarter.

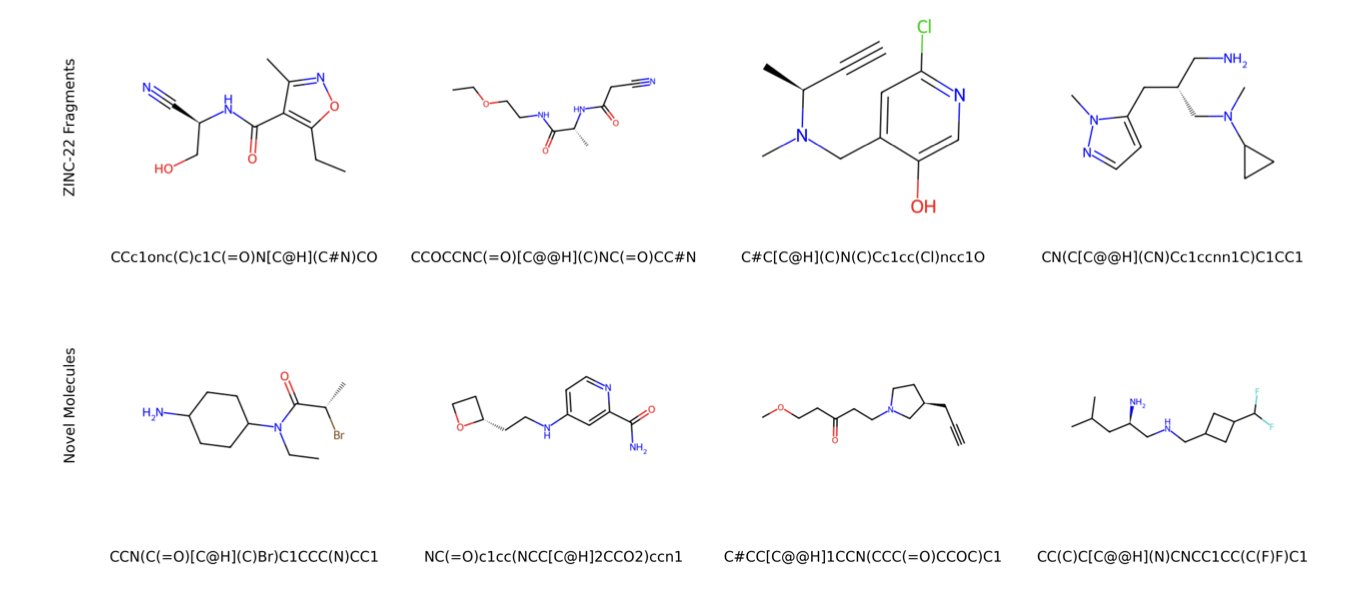

It is a Large Language Model (LLM), similar to GPT-4, but instead of learning human language, it learns chemical structures. Researchers trained it on over 62 million molecular fragments from the ZINC-22 database, teaching it the rules of “chemical grammar.” Once trained, the model can “write” new molecular fragments that follow these rules.

How Well Does It Work?

The model learned its “grammar” well. 99.9% of the molecular fragments it generates are chemically valid, so it doesn’t just invent structures that violate the principles of chemistry. A tool is useless if most of its output is noise.

The model also strikes a balance between “review” and “innovation.” Of the fragments it generated, 53.55% were known fragments from the ZINC database, proving it mastered existing core chemical patterns. At the same time, it created 22.04% entirely new structures. A t-SNE visualization analysis (see image above) shows that the chemical space distribution of these new fragments (Novel) highly overlaps with the known ones (Rediscovered). This suggests the new fragments have chemical properties similar to known high-quality fragments, giving them potential as starting points. It’s like a musician who can play the classics but also improvise.

The Value of Being Open-Source

The model’s biggest advantage is that it’s open-source. The research team has made the model, code, and data public. This means anyone with moderate computing resources, whether at a large company or a university lab, can deploy and use it. Researchers can use it to quickly generate virtual libraries with tens of thousands of novel fragments for virtual screening or to inspire synthesis targets. It acts like a tireless and creative assistant.

Limitations

The model has its limitations. First, it works with SMILES strings, a one-dimensional representation of chemistry that doesn’t capture a molecule’s 3D conformation or stereochemistry. In drug discovery, a molecule’s 3D shape determines whether it can bind to a target. The model provides a 2D “blueprint,” but a chemist still needs to figure out the 3D structure. Second, the model only generates the “bricks,” not instructions on how to build with them. It doesn’t offer strategies for linking fragments. The leap from fragments to a lead compound remains the art of medicinal chemistry.

Overall, FragAtlas-62M is positioned as a powerful tool to assist chemists, not replace them. It expands the search for drug starting points, revealing possibilities that would be difficult to find with human effort alone. The model frees chemists from the tedious search for “bricks,” allowing them to focus on combining high-quality fragments into effective drugs.

📜Title: A Foundation Chemical Language Model for Comprehensive Fragment-Based Drug Discovery 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.19586

3. AIDD: Fusing a Large Model’s Knowledge with Molecular Structure

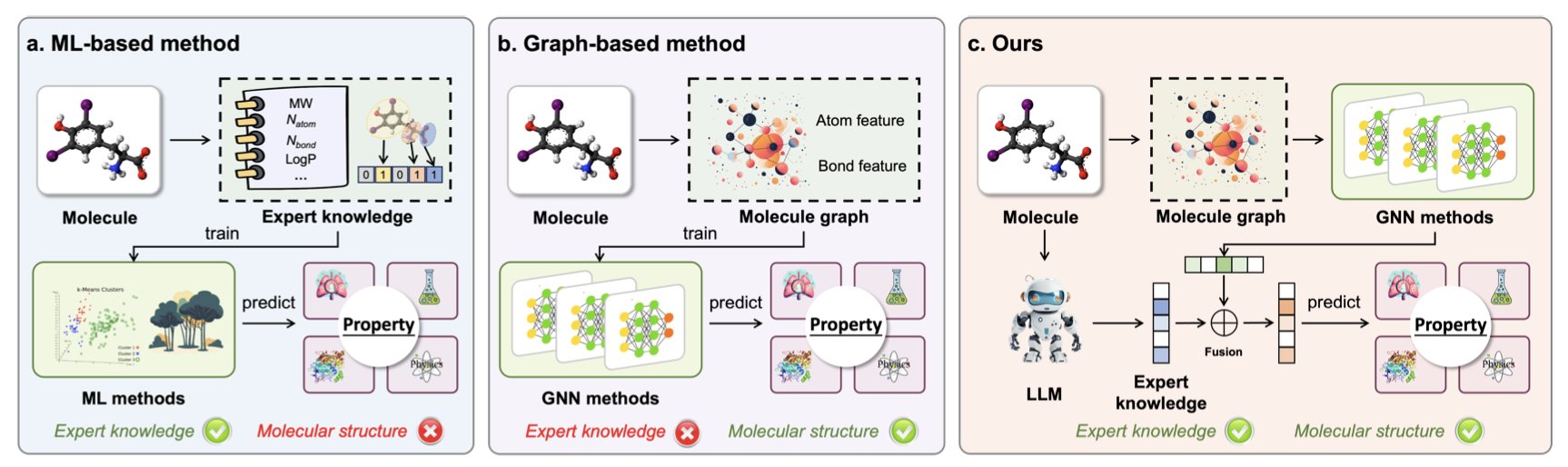

In computer-aided drug discovery, there are typically two ways to predict a molecule’s properties. The first uses models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to directly analyze a molecule’s 2D or 3D structure. This approach is good at finding patterns in structures, but it’s like a mathematician who understands geometry but not chemistry; it lacks the “chemical intuition” for higher-level concepts like functional groups or reactivity.

The second approach uses a Large Language Model (LLM) to read chemical literature. It can understand many chemical concepts but sometimes “hallucinates,” making up facts, and doesn’t have a deep understanding of specific molecular structures.

This paper proposes a method that combines the strengths of both.

Instead of asking an LLM to directly predict a molecule’s properties, the researchers first use it as a “consultant.” They prompt the LLM (like GPT-4o) to generate relevant chemical knowledge about a specific molecule, or even generate Python code to calculate molecular descriptors. This is like asking a senior chemist to write down their key thoughts upon seeing a molecule, such as, “This structure contains a Michael acceptor, which could cause off-target toxicity,” or “This fused ring system is planar and might have hERG issues.”

Then, the researchers take these “knowledge features” generated by the LLM and combine them with traditional “structural features” extracted from the molecule’s graph structure. This fused feature vector is then fed into a simple predictive model.

This approach covers the blind spots of both methods. The molecular structure information acts as a safety net, providing a solid physical basis for the prediction that can correct for an LLM’s flights of fancy. The chemical knowledge from the LLM adds rich chemical context to the otherwise cold structural data. The improvement is especially noticeable when dealing with properties like biological activity or ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity), where data is sparse and the patterns are complex.

The researchers tested their method on several public datasets. The results showed that this dual-source “knowledge + structure” approach consistently outperformed methods that used only a single source of information. They also compared the quality of knowledge generated by different LLMs (GPT-4o, GPT-4.1, and DeepSeek-R1).

This framework provides a practical example of how to use LLMs to empower drug R&D. It turns the AI into an assistant that can translate vast amounts of literature knowledge into usable computational features, rather than a replacement for scientists.

📜Title: Enhancing Molecular Property Prediction with Knowledge from Large Language Models 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.20664

4. Eigen-1, a New Take on AI Multi-Agents, Makes Scientific Reasoning More Accurate and Efficient

Large Language Models (LLMs) do well on general problems, but they often struggle with complex scientific reasoning tasks in areas like biochemistry. They may lack specific domain knowledge or get lost during multi-step reasoning. A new paper introduces the Eigen-1 framework, which offers a new solution.

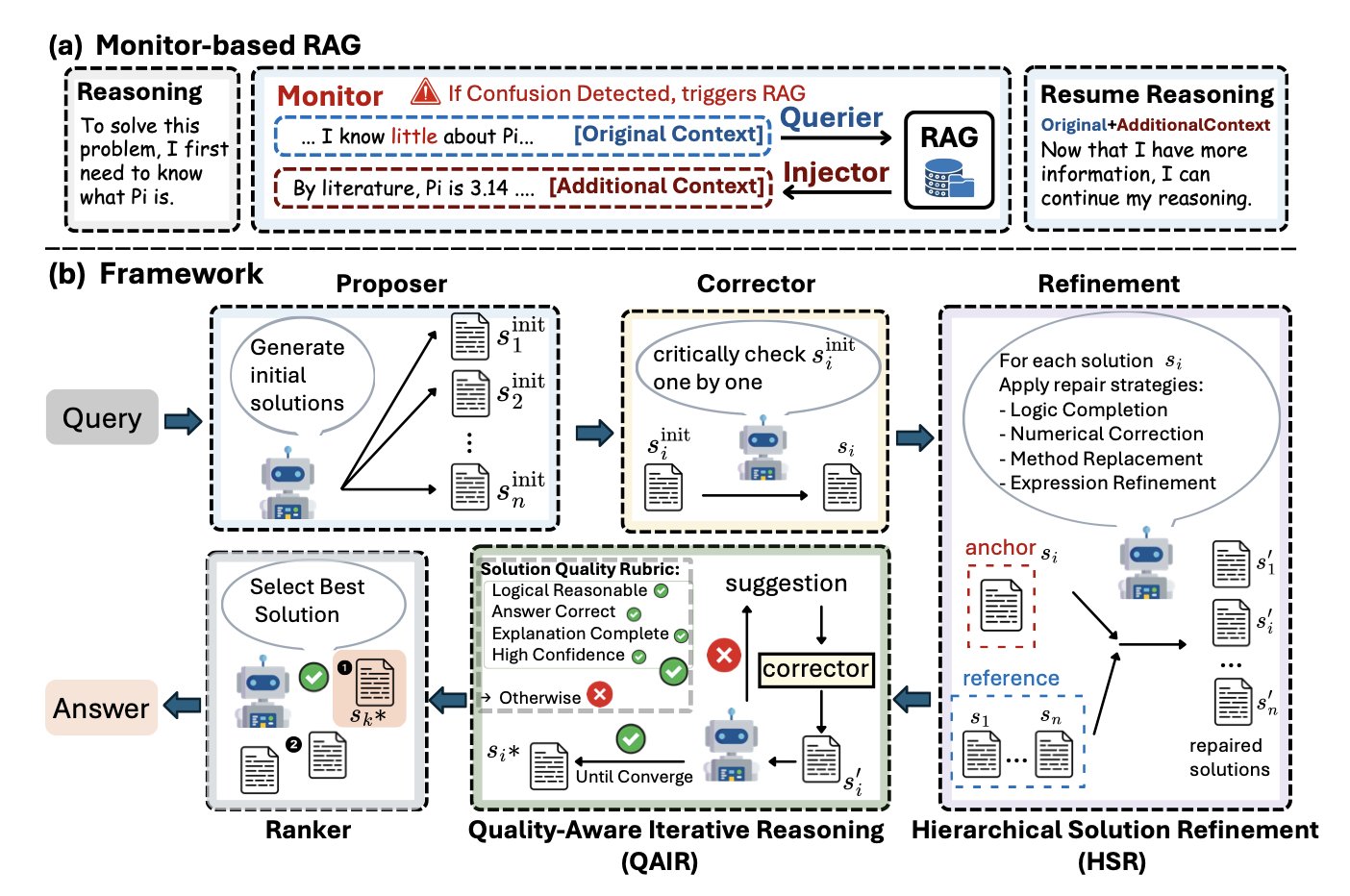

Letting AI Access Knowledge “Unconsciously,” Like an Expert

In scientific work, knowledge becomes second nature. When you think about a problem, relevant facts just come to mind; you don’t have to stop and look things up every step of the way. Traditional Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is like the latter—it requires the AI to explicitly call a tool to find information, which interrupts its train of thought.

Eigen-1 is designed differently. It uses a “Monitor-based RAG” mechanism. This system works at the token level, acting like an always-on monitor that constantly detects “knowledge gaps” in the AI’s reasoning process. As soon as a gap is found, it seamlessly supplies external knowledge without disrupting the AI’s main reasoning flow.

This is like an experienced scientist solving a problem. Relevant information naturally surfaces in their mind to support the next step, without them having to stop and ask what they need to look up. This approach makes the AI’s reasoning process smoother and deeper.

From “Democratic Voting” to “Peer Review”

When faced with a complex problem, people often come up with several possible solutions. Traditional multi-agent systems have each agent generate a solution and then vote for the best one. This is simple, but it often selects the most “average” answer, not the most correct one.

Eigen-1 uses a model closer to scientific collaboration: “Hierarchical Solution Refinement” (HSR). Here’s how it works: 1. The system generates multiple candidate solutions. 2. It takes each solution in turn and designates it as the “anchor.” 3. The other solutions act as “peers” to review and correct the anchor solution.

This process is similar to a paper’s peer review. Each reviewer (the other solutions) points out the strengths and weaknesses of the current paper (the anchor solution) from its own perspective and suggests revisions. Through this structured cross-review and repair, the quality of each solution is systematically improved, resulting in a more rigorous and reliable final solution that has been refined through multiple rounds.

Knowing When to Stop: Smart, Efficient Iteration

Research requires knowing when not to spend too much time on a problem that’s already good enough. Eigen-1 addresses this with its “Quality-Aware Iterative Reasoning” (QAIR) mechanism.

After each round of solution refinement, QAIR assesses the quality of the result. If the solution is good enough, or if the marginal benefit of further refinement is low, the system stops iterating. This adaptive approach ensures that computational resources are spent where they matter most.

On the HLE bio/chem gold-standard benchmark, Eigen-1 achieved an accuracy of 48.3%, surpassing previous models. At the same time, it reduced token usage by 53.5% and agent execution steps by 43.7%. It is not only more accurate but also faster and more cost-effective.

For fields like drug R&D, which require extensive computation and reasoning, this kind of efficiency gain is significant. It means more possibilities can be explored in less time and at a lower cost. Eigen-1’s approach of mimicking how human experts seamlessly access knowledge and collaborate through peer review offers a promising direction for AI in solving frontier scientific problems.

📜Title: Eigen-1: Adaptive Multi-Agent Refinement with Monitor-Based RAG for Scientific Reasoning 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.21193

5. AI Drug Discovery: ExMolRL Unites Phenotype and Target in a Two-Pronged Attack

In drug discovery, the search for new medicines has long followed two separate paths.

The first path is “phenotypic screening.” This is like the ancient method of testing herbs—you apply a large number of compounds to cells and see which ones produce the desired effect, like killing cancer cells. The advantage of this approach is that it’s results-oriented; you can find an effective molecule even if you don’t know its target. The downside is its “black box” nature, which makes it difficult to understand the mechanism and optimize the molecule later.

The second path is “target-based drug design.” This is like precision guidance. You first identify a key protein (the target) involved in a disease and then design or screen for molecules that bind to it, like making a key for a specific lock. This approach has a clear goal, but it’s risky. If you pick the wrong target, or if a single target isn’t enough to treat a complex disease, all subsequent work may be for nothing.

Ideally, drug discovery should combine the strengths of both strategies: the guaranteed results of phenotypic screening and the precision of target-based design. The ExMolRL framework was designed to do just that.

Its design involves two steps.

First, it trains a molecule generator on massive amounts of “drug-transcriptome” data. The AI learns how different drugs cause changes in gene expression in cells, essentially mastering a “drug-effect fingerprint library.” Through this learning, the AI can predict the likely cellular phenotype for a given molecular structure. For example, it can learn to recognize the molecular features that might kill A549 lung cancer cells.

Second, it uses Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning to fine-tune the model. Reinforcement learning is like training an AI to play a game: you set the rules and give rewards based on performance. Here, the goal of the game is to generate an ideal drug molecule, and the reward is determined by a composite function that balances several key metrics:

- Docking Affinity: The molecule must bind tightly to the specified target protein for a “precision strike.”

- Phenotypic Match (Ranking Loss): The molecule’s predicted gene expression profile must closely match the desired “anti-cancer” phenotypic profile to ensure it is “results-oriented.”

- Drug-likeness: The molecule’s physicochemical properties (like solubility and stability) must meet the standards for a drug.

- Synthetic Accessibility: The molecule must be chemically synthesizable, not just a theoretical construct.

- Diversity (Entropy Maximization): The model is encouraged to generate structurally diverse molecules to increase the chance of success.

This reward system guides ExMolRL to find the optimal balance. The molecules it generates are not just champions in a single category but are candidates with excellent all-around performance.

The results show that the molecules generated by ExMolRL are superior in target binding affinity, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility compared to traditional methods that focus only on the target or the phenotype. Furthermore, the computationally designed molecules showed stronger anti-cancer activity in cell experiments. This confirms the effectiveness of the dual “phenotype + target” strategy in discovering potential drug molecules.

Tools like ExMolRL offer a new paradigm for exploring chemical space in drug R&D. The molecules it designs are built from the ground up to have both target precision (hitting the right spot) and biological effectiveness (hitting hard), which could improve the success rate of early-stage drug discovery.

📜Title: ExMolRL: Phenotype–Target Joint Generation of De Novo Molecules via Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.21010v1