Table of Contents

- AlphaFold-Multimer predictions show that concatemer technology, used to dictate receptor subunit arrangement, is unreliable. Linker flexibility allows for unexpected subunit insertion.

- ToolUniverse is an open-source ecosystem that lets researchers build custom AI scientists for complex problems by unifying and automating how scientific tools are called, created, and optimized.

- The new MOLERR2FIX benchmark shows that even top large language models perform poorly at understanding and correcting errors in chemical text, meaning they are far from being reliable research assistants.

- BindPred accurately predicts protein binding affinity using only amino acid sequences, working quickly without needing 3D structures.

- Researchers have built a pharmacogenomic knowledge graph, validated with a strict timeline, that provides a reliable foundation for AI to discover new links between drugs, genes, variants, and diseases.

1. AlphaFold Reveals a Major Flaw in a Classic Receptor Research Technique

Determining how subunits are arranged in multi-subunit protein complexes, like nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), has always been a tough problem in structural biology.

For decades, researchers have used a technique called concatemerization to solve it. The method involves genetically linking subunits A and B with a flexible linker. When the cell expresses this, A and B form a single polypeptide chain, which should ensure they sit next to each other in the final complex. It’s like tying two LEGO bricks together with a string to keep them adjacent. This technique is widely used for important proteins like nAChRs and GABA receptors.

But research from Hanna M. Sahlström’s team challenges this long-held assumption. They studied the nAChRs of the parasitic sea louse (Lepeophtheirus salmonis). These receptors are key targets for insecticides, so their exact structure is critical for developing new drugs.

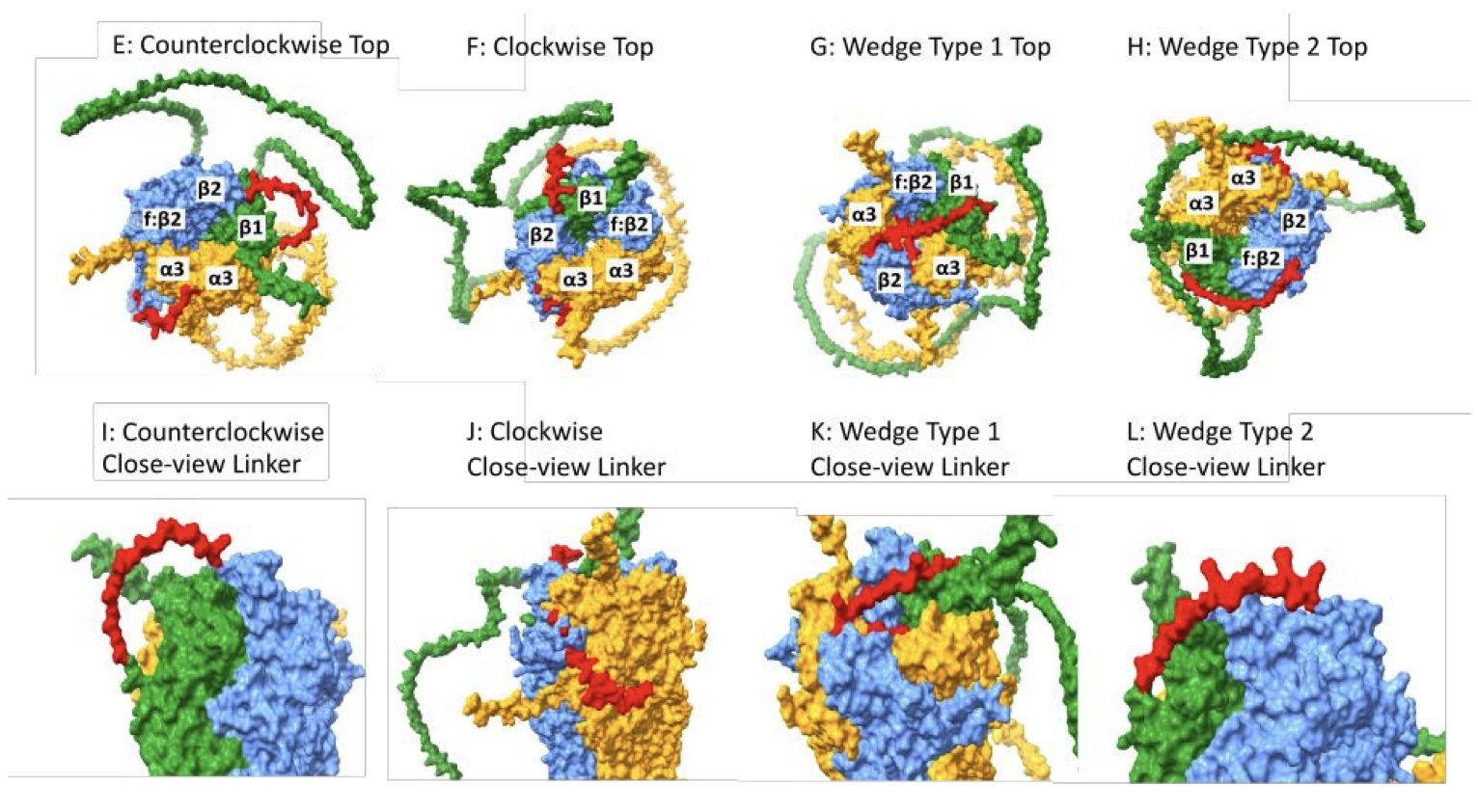

Using AlphaFold-Multimer to predict how the subunits assemble into a pentameric receptor, they found something unexpected. The model showed that even when two subunits are tethered by a linker, they might not end up next to each other in the final complex.

That linker “string” is much longer and more flexible than previously thought. Its flexibility allows a separate, free-floating subunit to wedge itself between the two linked subunits. The researchers named this phenomenon “wedging.” As a result, the intended “A-B” arrangement could actually form an “A-C-B” configuration.

This has major implications for drug development. Drugs often act at the interface between subunits. If the model of subunit arrangement is wrong, designing a drug is like making a key for the wrong lock—it will fail.

The problem isn’t limited to nAChRs. The conclusions of any study that used concatemers to infer subunit stoichiometry are now questionable. Much of the accepted knowledge about receptor structures may need to be re-examined with new tools like AlphaFold.

The computational predictions were confirmed by experiments. The team expressed the unexpected combinations predicted by the model in Xenopus laevis oocytes and found that they did form functional ion channels.

This study shows how computational tools can uncover blind spots in traditional experimental methods. AlphaFold is no longer just a tool for predicting protein structures; it is becoming a force for challenging and correcting our basic understanding of complex biological systems.

📜Title: AlphaFold-Multimer Modelling of Linked nAChR Subunits Challenges Concatemer Design Assumptions 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.02.679753v1

2. ToolUniverse: Build Your Own AI Scientist to Speed Up Drug Discovery

In drug discovery, we deal with all kinds of software tools every day: molecular docking, ADMET prediction, gene sequence analysis. Each tool has its own quirks and requires its own language. Getting them to work together is like organizing a United Nations meeting—you first need to hire a bunch of interpreters. It’s a painful and inefficient process.

ToolUniverse, developed by a team at Harvard, aims to solve this by creating a universal operating system for all scientific tools.

How does it work?

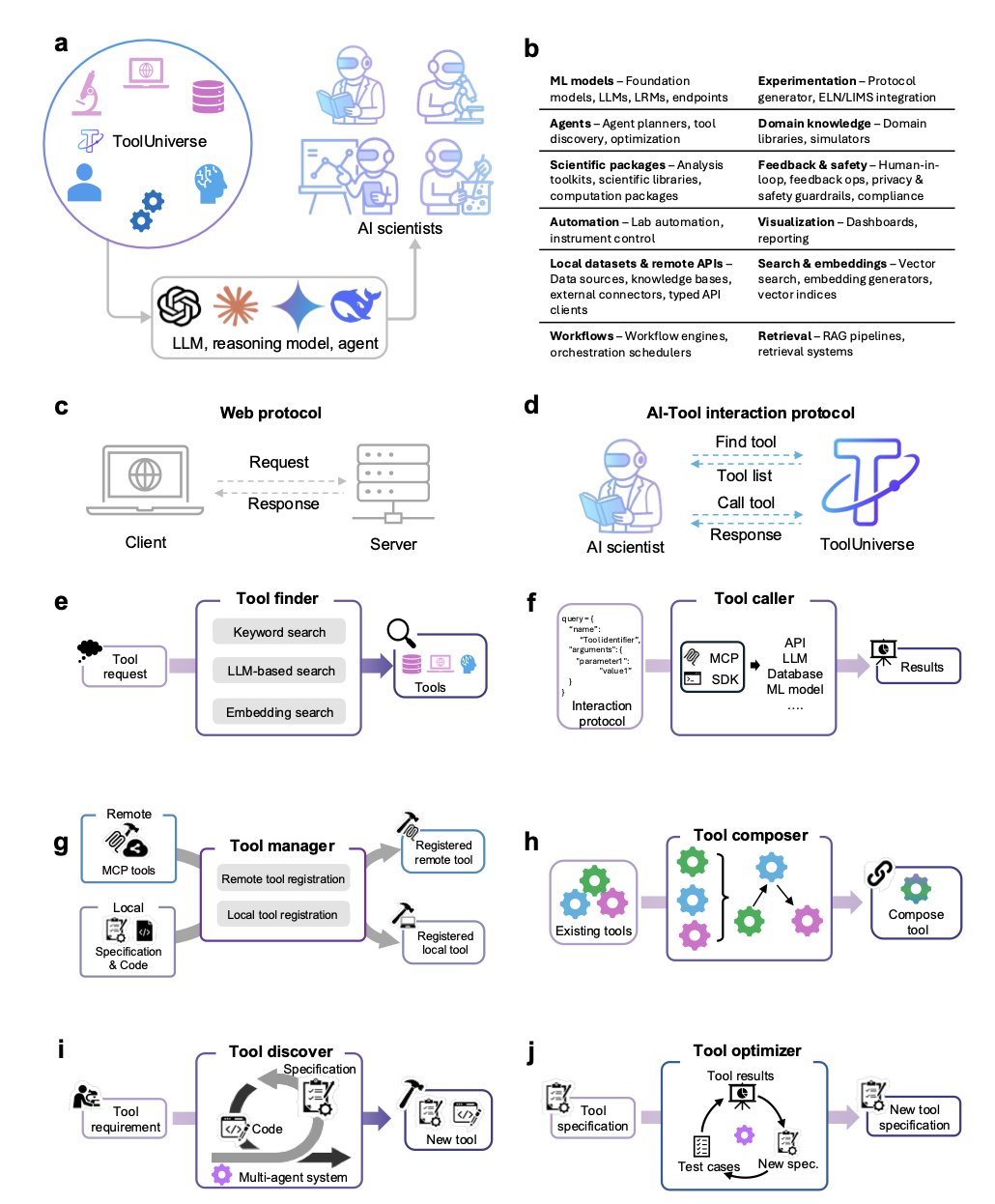

The system’s core has just two actions: Find Tool and Call Tool.

The researchers registered over 600 machine learning models, database APIs, and scientific computing packages into ToolUniverse. They described each tool’s function, input, and output using a standardized specification schema.

This way, the AI doesn’t have to learn a new way to call each tool. It can find the right tool with Find Tool, like looking up a book in a library, and then use the single, unified command Call Tool to run it. This system breaks down the barriers between different tools, making it possible to build complex, automated workflows.

Create tools with natural language

ToolUniverse not only unifies existing tools but also helps create new ones.

It can automatically generate an executable new tool from a few sentences of natural language. For example, you could tell it: “I need a tool that takes a compound’s SMILES string as input and uses RDKit to calculate its molecular weight and logP.”

After receiving the instruction, ToolUniverse automatically generates a standardized specification, writes the Python code, creates test cases to validate it, and refines the tool through feedback. The entire process requires no human intervention. This allows non-programmers to quickly create custom tools and integrate them seamlessly into AI-driven research workflows.

A case study in hyperlipidemia drug discovery

To demonstrate the system’s utility, the researchers built an AI scientist to study hyperlipidemia.

The AI scientist started by forming a hypothesis and then independently called various tools: 1. It used a literature mining tool to identify disease-related targets. 2. It used a compound screening tool to search for potential molecules in a virtual library. 3. It used a patent evaluation tool to check the novelty of the candidate molecules. 4. It used a property prediction tool to assess the molecules’ druggability.

In the end, the AI discovered an analog of an existing drug and predicted it would have better pharmaceutical properties. This case study shows how an AI scientist can use ToolUniverse to handle complex discovery tasks, from early exploration to candidate molecule validation.

ToolUniverse presents a new vision for researchers on the front lines. The goal is to give every scientist a capable, obedient AI assistant that can constantly learn new skills. This assistant handles the tedious work of calling tools and writing code, letting scientists focus on solving scientific problems.

📜Title: Democratizing AI scientists using ToolUniverse 🌐Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.23426v1 💻Code: https://github.com/mims-harvard/ToolUniverse

3. An LLM Chemist? New Benchmark MOLERR2FIX Shows Critical Flaws

We handle chemical literature all the time. If an assistant can’t even tell whether a molecular structure described in a text is right or wrong, it’s useless—and potentially dangerous. Many people talk about how Large Language Models (LLMs) will transform chemical research, but whether they truly “understand” chemistry is a key question.

A new benchmark called MOLERR2FIX has provided an answer.

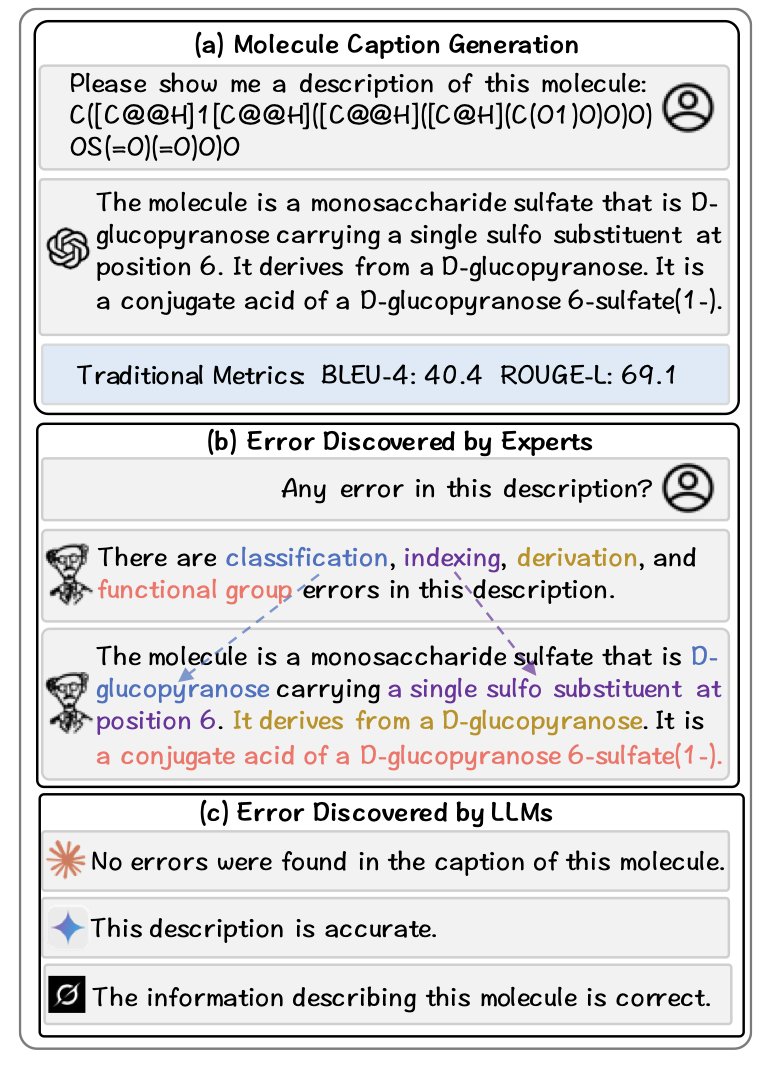

The test is designed to mirror the daily work of a research scientist. Some past benchmarks mostly tested a model’s ability to do “translation,” like converting a chemical formula (SMILES) into descriptive text. That’s like describing a picture; the model just needs to memorize patterns. But MOLERR2FIX asks the model to act as a peer reviewer.

Specifically, it gives the model a piece of text describing a molecule, which may contain various errors. The model’s task has four steps: 1. Detection: Determine if there is an error in the text. 2. Localization: Pinpoint the specific word or phrase that is wrong. 3. Explanation: Explain why it is wrong. This tests real chemical knowledge. 4. Revision: Provide the correct text.

A model has to complete this entire process to be considered a competent chemistry assistant. For example, the text might describe “a carbon atom with seven bonds.” The model needs to not only spot that this is impossible but also explain that “carbon typically forms only four covalent bonds due to its valence electrons” and then suggest a correct revision.

The researchers tested some of the most advanced models, including the general-purpose GPT-4 and the chemistry-focused ChemLLM. The results threw some cold water on the hype around AI in drug discovery.

The models performed acceptably on the first step, “Detection,” sometimes guessing correctly that the text was “problematic.” But their performance dropped sharply in the later, more detailed steps. They were especially bad at “Explanation,” often spouting nonsense that sounded technical but was chemically incorrect. In the “Revision” step, they frequently introduced new, more subtle errors.

Current LLMs are essentially statistics-based parrots. They can memorize and repeat vast amounts of chemical text, but they haven’t formed the kind of rule-based chemical “intuition” or “common sense” that human scientists have. An LLM knows that “carbon” and “four bonds” often appear together, but it doesn’t really “understand” why.

This conclusion is critical for researchers. In the short term, we cannot blindly trust any chemical content generated by an LLM. It might be fine for polishing an email or summarizing a paper’s abstract. But it is too early to let it participate in core R&D tasks that require precise judgment, like interpreting patents or designing synthesis routes. An AI that makes mistakes confidently is far more dangerous than one that admits it doesn’t know.

The MOLERR2FIX work uses a scientific and rigorous approach to identify the shortcomings of current technology and points the way forward. We need models with true chemical reasoning abilities, not just better language mimics.

📜Title: MOLERR2FIX: Benchmarking LLM Trustworthiness in Chemistry via Modular Error Detection, Localization, Explanation, and Revision 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.00063

4. BindPred: Predicting Protein Affinity from Sequence Alone, No 3D Structure Needed

Predicting the binding strength of two proteins is central to drug development. Traditional methods rely on 3D protein structures, which are determined through complex and time-consuming techniques like X-ray crystallography. Without a structure, researchers must turn to molecular docking or homology modeling, but these methods are computationally expensive and often introduce errors.

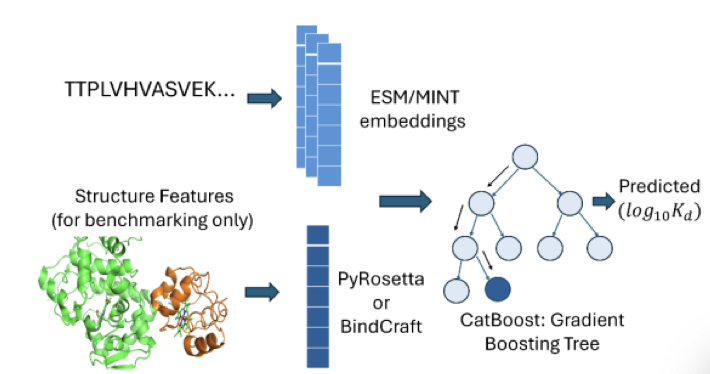

The BindPred framework bypasses 3D structures entirely.

Here’s how it works: it takes the amino acid sequences of two proteins and feeds them into a Protein Language Model, such as ESM2. These models have been trained on hundreds of millions of protein sequences and have learned the “grammatical rules” left by evolution. The model outputs a numerical vector called an “embedding,” which condenses the essential information from the sequence.

BindPred then feeds these two vectors into a gradient-boosted tree model, which directly predicts their binding affinity. The entire process goes from sequence input to affinity output in one step.

On the standard PPB-Affinity benchmark dataset, BindPred’s predictions achieved a Pearson correlation of 0.86 with experimental values.

A comparative experiment found that adding physics-based energy terms, calculated with traditional tools like PyRosetta and BindCraft, barely improved performance. This suggests that the evolutionary information extracted from the sequences by the protein language model already captures most of the key signals that determine binding affinity. It’s like trying to understand a book’s plot: reading the text directly is more effective than analyzing the physical properties of the paper and ink.

The value of this method lies in its speed and applicability. Because it doesn’t rely on structures, BindPred can evaluate about three million protein pairs per hour on a single T4 GPU. This is fast enough to screen interactions across the entire proteome, helping to find new leads for drug discovery or systems biology research.

To test the model’s ability to generalize, the researchers split the data by protein family, ensuring no overlap between the training and test sets. Even when faced with entirely new proteins, BindPred performed robustly. This proves it learns the general principles of protein binding rather than just memorizing training data—a critical feature for discovering new targets and molecules.

The research team has made the model and code available, along with a Google Colab notebook, making it easy for anyone to use. This should accelerate the adoption of this technology in both academia and industry.

📜Title: BindPred: A Framework for Predicting Protein-Protein Binding Affinity from Language Model Embeddings 🌐Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.09.27.678407v1 💻Code: https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

5. A New Tool for AI Drug Discovery: A Large-Scale Pharmacogenomic Knowledge Graph

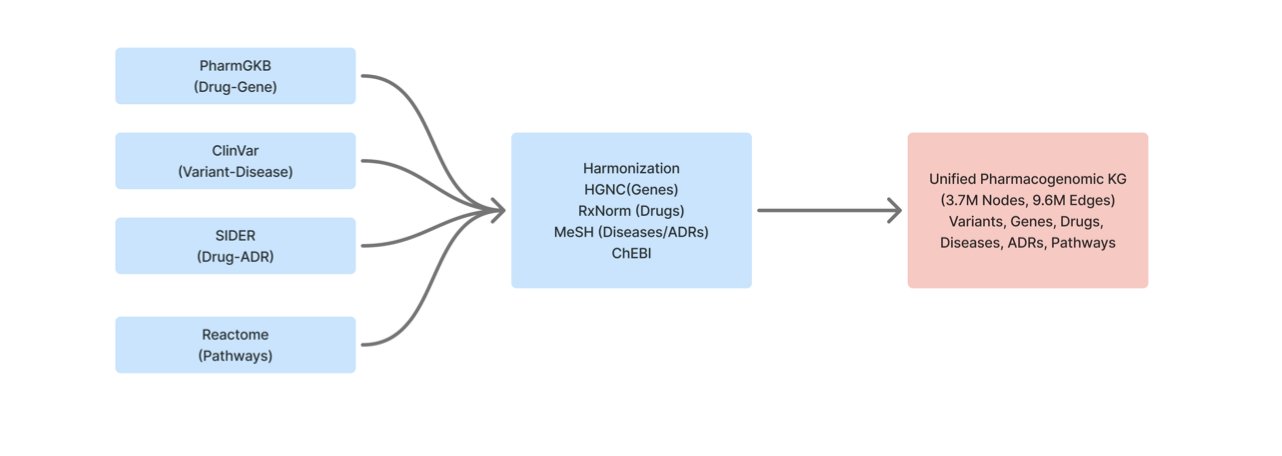

One of the big challenges in drug development is data silos. Information about drugs, genes, clinical phenotypes, and pathways is scattered across databases like PharmGKB, ClinVar, SIDER, and Reactome. Each database is like a separate box of puzzle pieces. This preprint describes the work of putting those pieces together—integrating, cleaning, and organizing them into one giant relationship map: the Pharmacogenomic Knowledge Graph (PGx-KG).

This map contains over 3.7 million nodes (like a drug or a gene) and 9.6 million edges (the relationships between nodes). It creates a huge network of biological relationships, allowing us to see connections like “Drug A inhibits Target B” or “A mutation in Gene C causes Disease D.”

Building the graph is just the first step. What makes this work stand out is its data handling. A common pitfall in AI prediction is “data leakage,” especially “temporal leakage.” It’s like using tomorrow’s newspaper to “predict” today’s stock prices—your accuracy will be high, but it’s meaningless. In drug discovery, if you train a model on data published in 2023 to “predict” a drug-target relationship that was already known in 2021, the model’s performance will be inflated and useless for real R&D.

The authors designed a “leakage-free” process. They timestamped all the data and split it strictly by publication date. When training their models, they only used “past” data to predict “future” relationships. This approach makes the model’s evaluation honest and reliable. When they report a Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) of 0.347 for their link prediction model, that number was obtained by simulating a real-world research scenario.

What can this graph and model do? It acts like a “relationship detective,” analyzing known connections in the network to predict “missing links” that likely exist but haven’t been discovered yet. For example, it might propose a new hypothesis: “A certain cancer drug might also be effective for treating a rare genetic disease.” This is drug repositioning. The researchers showed that the model can uncover some potentially meaningful clinical connections.

This work provides a more reliable infrastructure for AI drug discovery, connecting molecular-level mechanisms (gene variants) with macro-level clinical phenomena (drug efficacy or toxicity). The authors plan to test more advanced Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on this foundation and integrate real-world evidence. They have released their code and processed data, so the entire community can build on their work.

📜Title: A Large-Scale Pharmacogenomic Knowledge Graph for Drug-Gene-Variant-Disease Discovery 🌐Paper: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.09.24.25336269v1