Table of Contents

- The DlRNA-BERTa model merges language models for RNA and small molecules to predict binding affinity without 3D structures, offering a powerful new tool for targeting RNA.

- The MolecularWeb ecosystem uses web-based AR/VR to transform molecular visualization and modeling from complex mouse-and-keyboard tasks into an intuitive, collaborative, hands-on experience.

- By integrating known biological pathway knowledge into a graph attention network, a model can more accurately predict cellular responses to drugs and also infer gene interactions from the data.

1. AI Predicts RNA-Drug Binding Without 3D Structures

Targeting RNA is an appealing but difficult challenge. Proteins usually have well-defined pockets for drugs to bind, but RNA is more like a flexible noodle, constantly changing shape. This makes structure-based drug design for RNA targets very hard. If we could skip the 3D structure and predict whether a small molecule binds to an RNA sequence directly, it would change everything.

This is the problem the new DlRNA-BERTa model tries to solve.

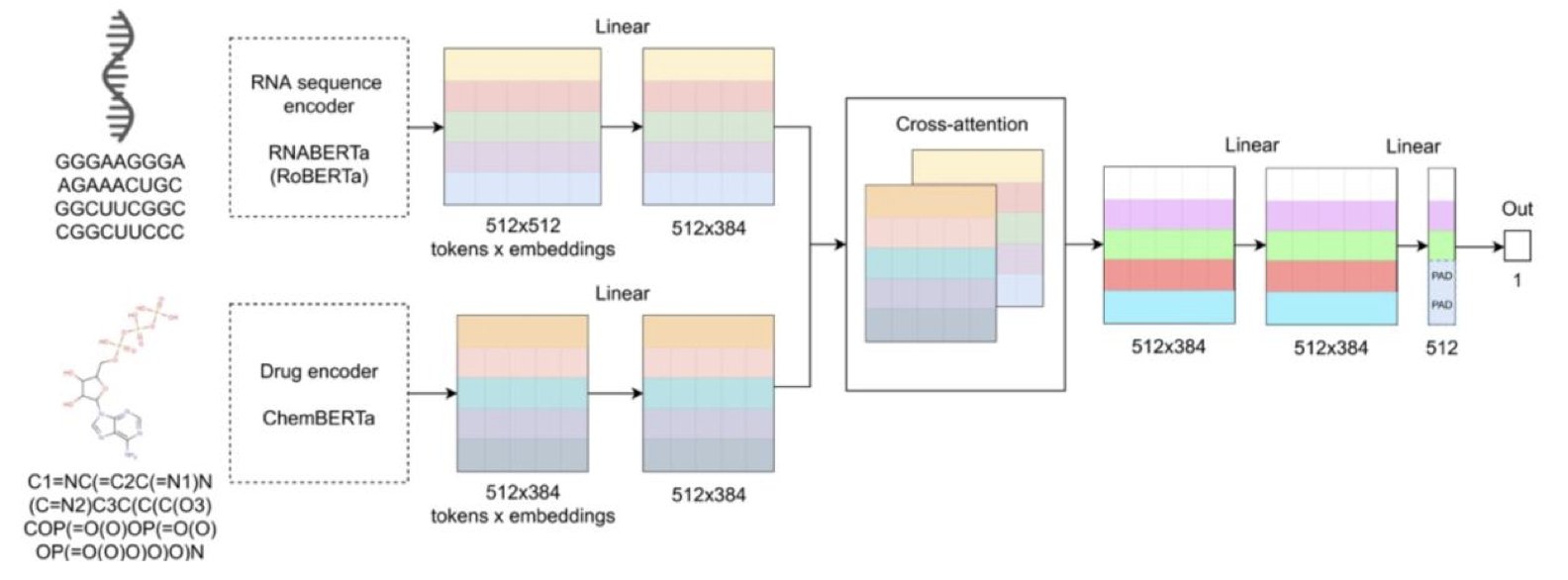

The core idea is clever. Instead of starting from scratch, the researchers built on existing work. They used two pre-trained “expert” models: one called RNABERTa, which has read nearly 10 million RNA sequences and understands the “language” of RNA; the other is ChemBERTa-v2, which has studied countless small molecules and knows the “grammar” of chemistry.

Think of DlRNA-BERTa as a coordinator whose job is to get these two experts to talk. It uses a module called a “cross-attention mechanism.” This mechanism is like a roundtable meeting where the coordinator constantly asks the RNA expert, “Which part of your sequence is the chemistry expert most interested in?” while also asking the chemistry expert, “Which group in your molecule is the RNA expert focused on?” Through this back-and-forth pointing, the model identifies potential interaction sites between the RNA sequence and the drug molecule. It then outputs a predicted binding affinity score.

The whole process is end-to-end. We just input the RNA’s base sequence and the drug’s SMILES string, and the model gives us a result. This completely bypasses the difficult step of obtaining a complex 3D RNA structure.

So how well does it perform? For a class of molecules called microRNAs (miRNAs), the Pearson correlation coefficient between predicted and experimental values reached 0.98. In biological prediction, that’s a high number, suggesting the model has captured key principles behind the binding event.

A specific example makes this more convincing. The researchers used the model to screen over 3,000 approved drugs and found that 2,859 of them could potentially bind to 294 RNA targets. The model gave a high score to the binding between the anticancer drug bleomycin and RNA. We know bleomycin is an old drug that works mainly by inserting itself into DNA, but existing literature shows it also binds to RNA. The fact that the model made this prediction without any prior knowledge is like it “rediscovered” a known biological fact. This kind of validation gives us confidence that it can also discover new, unknown drug-RNA interactions.

The model has a lot of practical value. First, it performs well even on RNA types with little experimental data, like riboswitches. This means it has broad applications beyond a few well-studied RNA molecules. Second, the researchers have made their work completely open. They published the paper and also released the code, datasets, and an online prediction tool. This means researchers in both academia and industry can start using this tool right away to screen compound libraries and find potential hits for their RNA targets.

This provides a powerful search engine for the early stages of RNA-targeted drug discovery. Instead of searching in the dark, we can use this model for large-scale virtual screening, focus on a small set of promising molecules, and then commit resources to experimental validation. This improves R&D efficiency.

📜Title: DlRNA-BERTa: A Transformer Approach for RNA-Drug Binding Affinity Prediction 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.09.05.674445v1 💻Code: https://github.com/IlPakoZ/rnaberta-dti-prediction 🌐App: https://huggingface.co/spaces/IlPakoZ/DLRNA-BERTa

2. MolecularWeb: Grab Molecules with Your Bare Hands in AR/VR

People in drug development spend most of their time working with molecules. But how do we do it? We stare at a 2D screen, using a mouse to rotate and zoom a 3D object. It’s like trying to understand a sculpture by looking at photos. We get the information, but something feels missing. We lose our intuition for the molecule’s shape, volume, and spatial relationships.

A new preprint introduces an ecosystem called the “MolecularWeb Universe” that tries to fix this. The core idea is simple: instead of looking at the screen, let’s step inside.

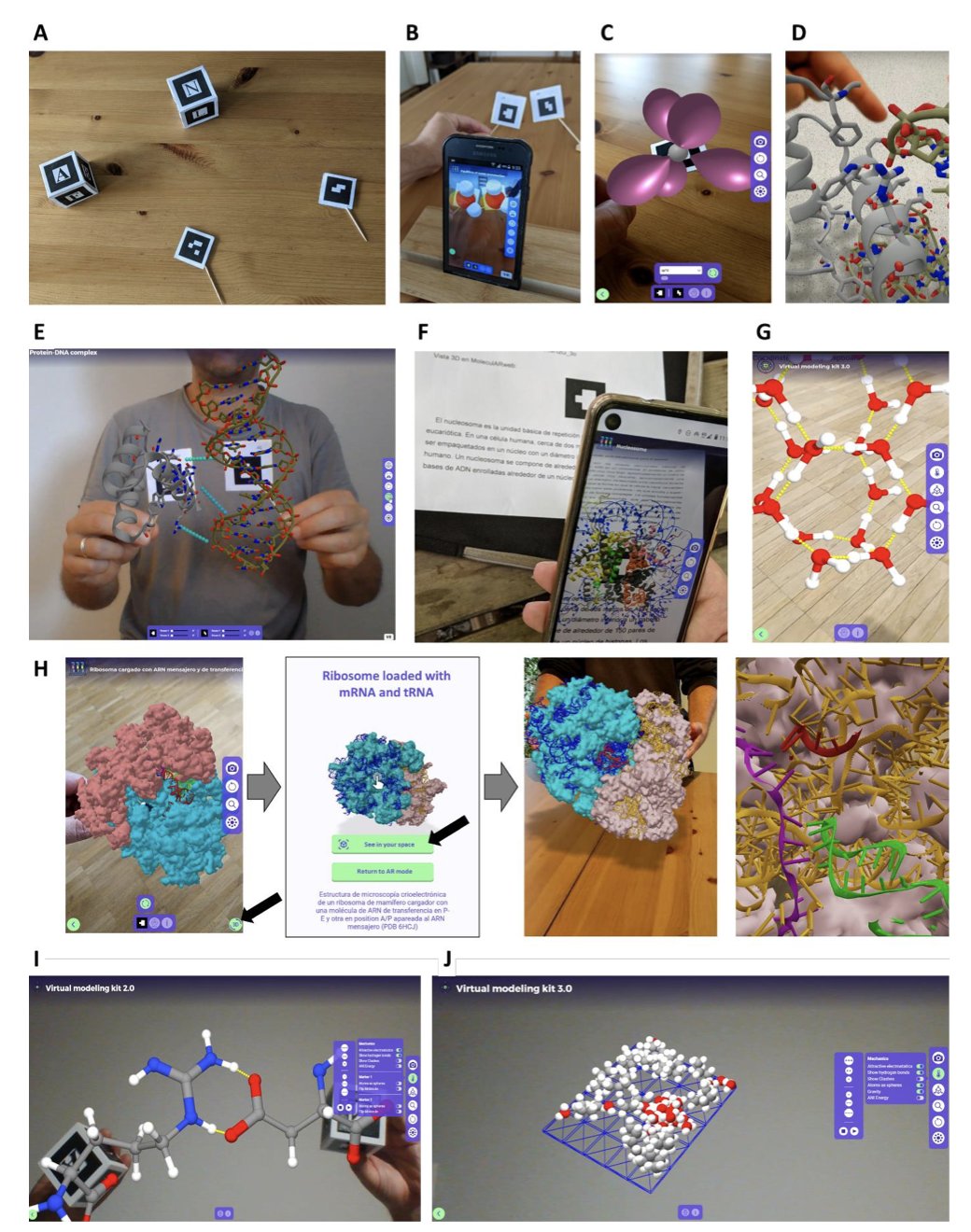

First, bring molecules into the real world

The ecosystem includes a tool called moleculARweb. It lets you use your phone or tablet to project a protein structure onto your conference room table. This is Augmented Reality (AR). Imagine a team meeting to discuss a target. Everyone can walk around the 3D model, seeing from their own perspective how a ligand fits into the active site. This kind of communication is far more efficient than any 2D screenshot or screen share.

Second, let the team meet inside the molecular world

For a more immersive experience, there’s MolecularWebXR. It supports multi-user Virtual Reality (VR). Team members in different cities can put on VR headsets and enter the same virtual room. Together, they can stand next to a giant, interactive kinase-inhibitor complex. A chemist could reach out and point to a specific benzene ring they plan to modify, while a computational scientist could pull up energy calculation results and attach them to that ring in real time. This is true collaboration.

To make all this practical, the researchers developed the PDB2AR tool. It can quickly convert any file from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), or your own structure, into an AR/VR-compatible model. This means you can immediately apply the technology to your own projects, not just play with pre-loaded examples.

The real shift: “Creating” molecules with hands and voice

The most impressive part of this ecosystem is HandMol. It moves beyond observation and into modeling. In a VR environment, you can directly grab a molecule with your “hands” and twist its single bonds like a piece of dough to feel the conformational changes. As you do this, the system runs molecular mechanics calculations in the background, telling you if the new conformation’s energy is high or low and whether it’s plausible.

It also integrates AI-driven Natural Language Processing (NLP). You don’t need to remember complicated commands or click through menus. You can just say to the system, “Highlight the loop between residues 50 and 65,” or “Measure the distance between this lysine and that aspartate.” The system understands your commands and executes them instantly.

This lowers the barrier to entry for molecular modeling. A structural biologist or medicinal chemist who isn’t an expert in computational chemistry can quickly build models and test their ideas. This intuitive way of working might help us discover structural features that are easy to miss with traditional methods. This system frees us from the keyboard and mouse, letting us explore and create molecules in a way that is more natural for humans.

📜Title: The MolecularWeb Universe: Web-Based, Immersive, Multiuser Molecular Graphics And Modeling, for Education and Work in Chemistry, Structural Biology, and Materials Sciences 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.04056v1

3. Using Graph Networks to Understand Biological Pathways

In computational biology, we’ve always wanted machine learning models to better understand biology. Often, we feed data into a “black box” model, like a Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP), and get a prediction. This sometimes works, but the model itself learns nothing about biological mechanisms. It just finds statistical patterns in the data, which limits its predictive power in new situations and leaves us wondering why it made a certain prediction.

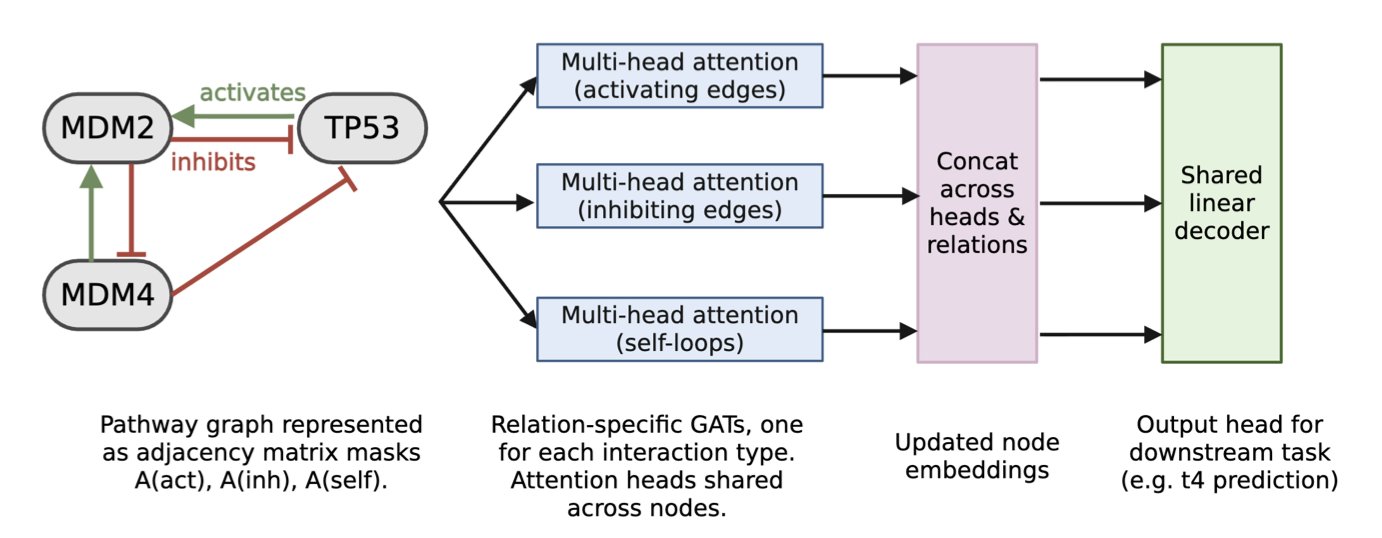

This paper describes an interesting attempt to change that. Instead of using a generic black box, the researchers chose a more structured approach: Graph Attention Networks (GATs).

This choice is a good one. A biological signaling pathway is already a network of genes (nodes) and their interactions (edges). The structure of a GAT naturally matches this network format. The researchers used known biological pathway maps as the model’s skeleton. This is like giving the model a biology lesson before training even begins, telling it, “This is how these genes are connected and influence each other.”

At the model’s core is an “attention mechanism.” It allows the model to dynamically learn the importance of different “edges”—the interactions between genes—during training. For example, under a certain drug treatment, the inhibitory effect of gene A on gene B might become critical, while other interactions become less important. The attention mechanism can capture these dynamic changes.

What were the results? When asked to predict gene expression under a drug treatment condition it had never seen before, this “biologically informed” GAT model had an 81% lower prediction error than a traditional MLP model. Integrating biological knowledge as a mechanistic prior really does make the model more powerful and generalizable.

To further test this, the researchers performed an experiment using “edge interventions” to simulate a drug’s mechanism of action in the model. For instance, if a drug blocks MDM2 from inhibiting P53, they would weaken or remove the corresponding edge in the graph. They found that this action further improved the model’s predictive accuracy. This shows that the model not only learned the pathway’s structure but also correctly understood how external interventions affect it.

The most exciting part is the model’s ability to “discover.” The researchers took the classic TP53-MDM2-MDM4 regulatory circuit and gave the model only the raw gene expression time-series data, without telling it the pathway structure. By learning from the data, the model accurately reconstructed the five known interactions between these genes.

This shows the potential. We can apply this type of model to less-studied signaling pathways, feed it experimental data, and let it infer potential unknown regulatory relationships. The model then transforms from a prediction tool into a discovery engine that can generate new biological hypotheses.

This work is still a proof of concept. It was tested on a simple pathway with only a few genes and a relatively small dataset. Real-world biological networks are much more complex. The next challenge will be to scale this approach to larger, more complicated systems. It combines data-driven machine learning with knowledge-driven systems biology, taking a step toward building AI models that can truly “understand” biology.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.00524v1