Table of Contents

- This work builds a zero-shot benchmark called DARKIN, which uses protein language models to find the phosphorylation substrates for “dark kinases” with unknown functions, opening up a new way to discover drug targets.

- Current molecular docking methods perform poorly when predicting the structures of macrocyclic host-guest complexes like cyclodextrins and cucurbiturils. Solving this problem requires a two-step strategy.

- For optimizing molecular glues, Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) is a reliable computational tool, but its high cost highlights the urgent need for more efficient initial screening methods.

1. AI Lights Up “Dark Kinases,” Bringing New Drug Targets into View

The protein kinase family is a gold mine. Drugs targeting kinases, from Gleevec to the various “-tinibs,” have changed how we treat many diseases. But the family has an open secret: the human genome codes for over 500 kinases, and the function of about 100 of them is still a mystery. We call them “dark kinases.” They are like dark matter in the universe—we know they exist, but we don’t know what they do, let alone how to target them.

The traditional way to solve this is through high-throughput screening in the lab, testing them one by one. It’s slow, laborious, and expensive. The authors of this paper came up with a better idea: what if we could get AI to predict which protein substrates these dark kinases phosphorylate?

The challenge is that we have almost no experimental data for dark kinases. Traditional machine learning models need lots of “kinase-substrate” pair data for training, which won’t work here. This is known as a “cold start” problem.

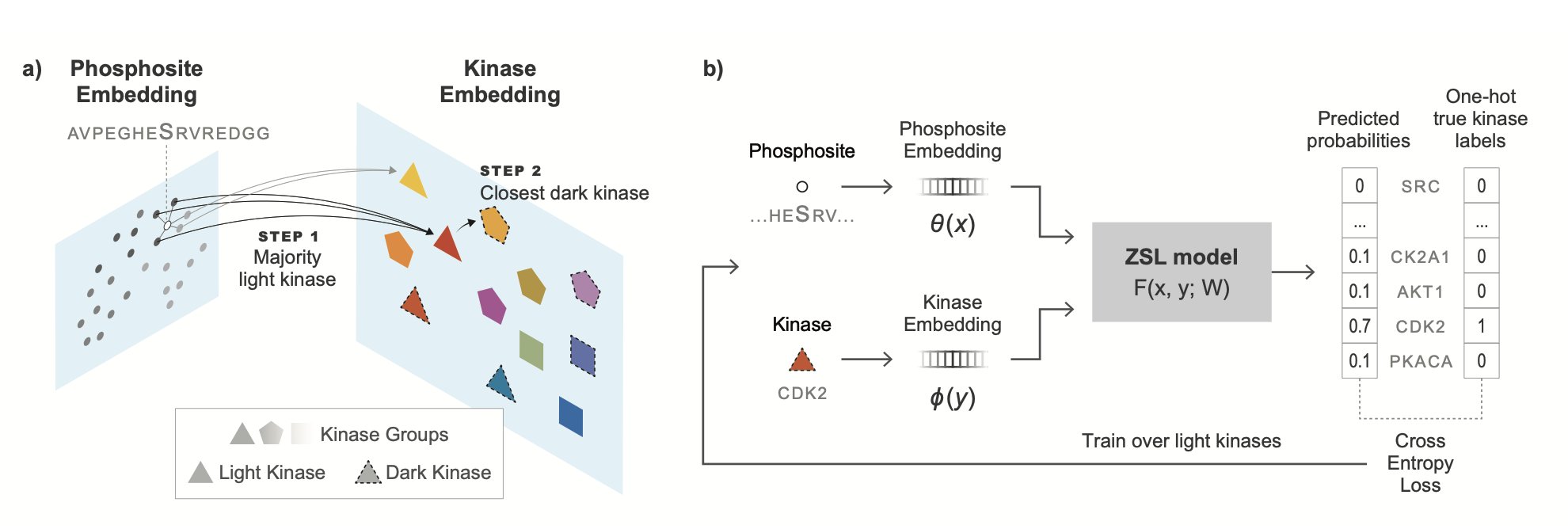

To solve this, the researchers designed a benchmark called DARKIN. Its core idea is zero-shot learning. Think of it like this: you teach a child to recognize various cats and dogs. Then you show them a photo of an animal they’ve never seen—say, a fox—and ask if it’s more like a cat or a dog. The child will make a judgment based on the general features they learned from cats and dogs (pointed ears, long tail, fur, etc.).

The DARKIN benchmark does just that. It splits known kinase data into a training set and a test set, but it does so carefully. It makes sure that the kinases in the test set, and the kinase families they belong to, never appear in the training set. This forces the model to learn the universal rules that determine function from protein sequences, instead of just memorizing “kinase A likes substrate B.”

They tested several protein language models (pLMs), like ESM and ProtT5. These models are like the GPT of the protein world; they’ve learned the “language” of proteins by “reading” vast numbers of protein sequences. The researchers first used the pLMs to convert the kinase and substrate sequences into strings of numbers (embedding vectors). Then, they used a simple classifier to determine if the two vectors “match.”

The results were interesting. The ESM, ProtT5-XL, and SaProt models performed best. This shows that these large models have indeed learned some deep biophysical knowledge about how kinases recognize substrates from massive amounts of sequence data. They can make pretty good predictions for a completely new kinase without direct training data.

Even more interesting, if you give the model some “hints”—like telling it which kinase subfamily the dark kinase belongs to, or its Enzyme Commission (EC) number—the model’s prediction accuracy improves significantly. This is practical because this information can often be inferred from a kinase’s sequence. It’s like telling the child, “This new animal you’re looking at belongs to the dog family.” That makes it much easier for the child to guess it’s a fox.

The authors also tried fine-tuning the models to focus them on this specific task, but the results were not stable. This suggests that the general knowledge from the pLM’s powerful pre-training might be more robust for handling this kind of zero-shot problem than specialized optimization on a small dataset.

The real value of this work is that it provides a computational roadmap for systematically exploring the “dark kinase” treasure trove. We can use this method to generate a high-confidence “potential substrate list” for hundreds of dark kinases. Then, experimental scientists can take this list and perform targeted validation instead of searching in the dark. Once we identify the function of a dark kinase, it goes from “dark” to “light” and becomes a potential new drug target.

📜Title: Darkin: A Zero-Shot Benchmark for Phosphosite–Dark Kinase Association Using Protein Language Models 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.27.672558v1

2. Predicting Macrocyclic Host-Guest Complexes with Molecular Docking: How Reliable Are Current Methods?

In drug development, macrocyclic molecules like cyclodextrins (CDs) or cucurbiturils (CBs) are often used as drug carriers to improve a drug’s solubility or stability. To design these carriers, we first need to accurately predict how the drug molecule (the guest) will bind with the macrocycle (the host). Molecular docking is a standard tool, but how well does it handle these types of macrocyclic complexes?

This preprint paper benchmarks eight common docking scoring functions, and the results are not promising.

The researchers discovered a dilemma. Scoring functions that are theoretically more accurate are computationally intensive, leading to “insufficient sampling” during the conformational search phase. On the other hand, fast, approximate scoring functions can generate binding poses but are too crude in describing intermolecular interactions. They might match the shape but fail to correctly identify key information like hydrogen bonds or electrostatic interactions.

Cyclodextrins and cucurbiturils present different computational challenges.

The portals of cucurbiturils (CBs) are typically negatively charged, so accurately handling electrostatic interactions is key to predicting their binding modes.

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are rings made of glucose units, with edges lined with similar hydroxyl groups that can all act as hydrogen bond donors or acceptors. This makes it difficult for docking programs to pinpoint the lowest-energy binding mode among many similar hydrogen-bonding sites.

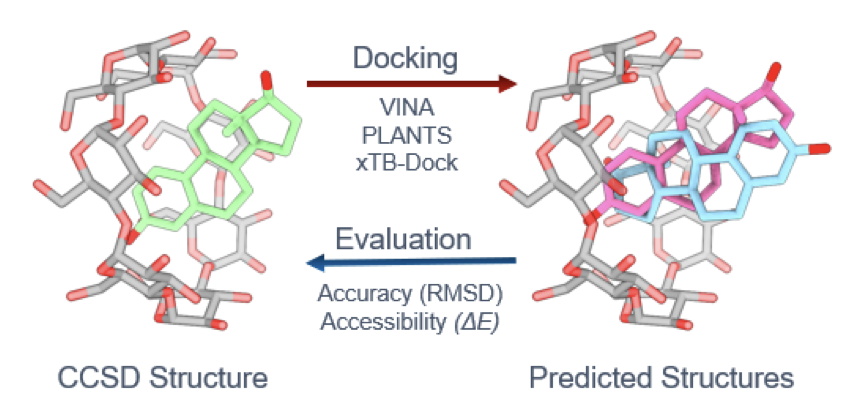

The researchers propose a workflow.

Step one is to use a fast, approximate scoring function for an initial conformational screen. This quickly generates a set of candidate poses and rules out obviously unreasonable ones.

Step two is to take these candidates and use high-accuracy methods, like quantum chemistry calculations, for a final evaluation to select the best solution.

The researchers also used quantum chemistry calculations to assess the thermodynamic stability of the predicted complexes. A crystal structure is a static snapshot, but in a solution, molecules are dynamic and can exist in multiple, energetically similar binding modes. These calculations can reveal which binding modes are stable at room temperature, which is more useful for carrier design.

📜Title: Evaluating Docking Approaches for Prediction of Cyclodextrin and Cucurbituril Host-Guest Complex Structures 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-qgpsj

3. A Guide to Optimizing Molecular Glues: FEP is Accurate but Expensive. What’s Next?

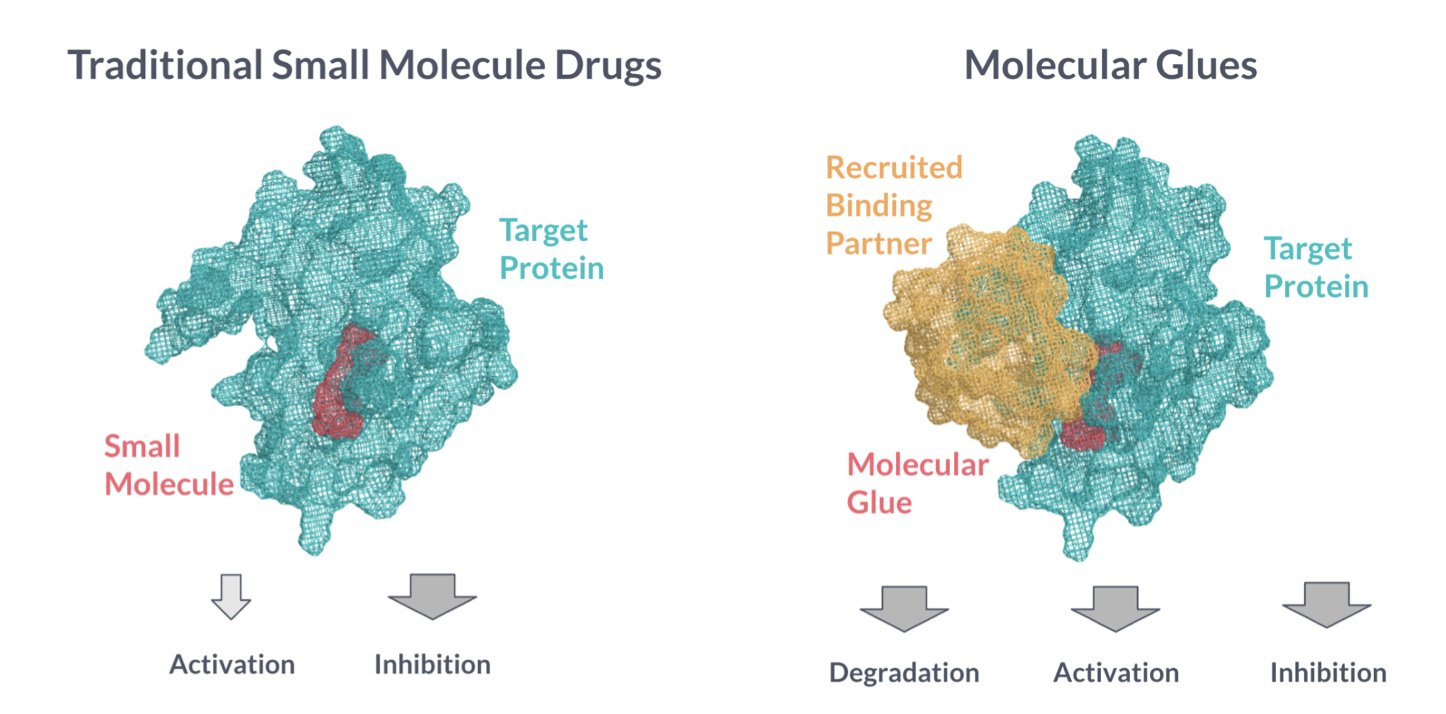

Developing molecular glues often feels like creating something out of thin air. In traditional drug design, we at least have a well-defined target pocket. Molecular glues are different; their binding site is often formed only at the moment one protein meets another. This dynamic, unstable ternary complex makes rational design tricky.

This is where computational chemistry becomes especially important. We need tools to predict which small molecule can better “glue” two target proteins together. The question is, which tools should we use?

This preprint paper systematically evaluates how well two mainstream computational methods predict the affinity of molecular glues. You can think of these methods as two different types of craftsmen.

The first is Free Energy Perturbation (FEP). This is like an experienced, meticulous master craftsman. FEP runs extensive, detailed molecular dynamics simulations to calculate the tiny energy changes in a system as one molecule “transforms” into another. The process is slow and requires a lot of computing power. But the results are usually accurate.

The second is Boltz-2. This is more like a fast-moving assembly line worker. It uses a scoring function to quickly estimate binding energy based on one or a few static structures. It’s fast and, in theory, suitable for initial screening of large compound libraries.

The researchers put these two methods to a real-world test on a fairly large dataset. They tested 93 compounds across 6 different protein complex systems, generating a total of 140 affinity data points. A benchmark of this scale is rare in the molecular glue field.

So what were the results?

FEP, the master craftsman, did not disappoint. The calculated changes in binding free energy (ΔΔG) correlated well with experimental values, with the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) kept between 0.3 and 1.25 kcal/mol. To put that accuracy in perspective, an energy difference of 1.4 kcal/mol in drug chemistry corresponds to a 10-fold change in affinity. So, FEP is precise enough to guide the structural optimization of lead compounds. For example, we can determine whether adding a methyl group at a certain position will strengthen or weaken the binding.

In contrast, Boltz-2’s performance was poor. Its predictions showed almost no correlation with the experimental data. This means it couldn’t even get the relative ranking of which molecules were better or worse right. For high-throughput screening, that’s a fatal flaw. Using it to screen for drugs is basically no better than random picking.

The takeaway from this work is direct.

First, if you already have a few good molecular glue candidates and need to fine-tune them, FEP is a trustworthy tool. It’s expensive, but it provides reliable direction.

Second, don’t count on using existing fast scoring functions for large-scale virtual screening of molecular glues. That approach doesn’t work right now.

This exposes a critical “methodology gap.” We have FEP, which is accurate but slow, and we have scoring functions that are fast but inaccurate. The middle ground is empty. We urgently need a “medium-throughput, medium-accuracy” method to screen millions of compounds down to a few hundred promising candidates. Then we can hand those over to FEP for detailed work.

This is exactly where machine learning models could shine. Developing more accurate machine learning scoring functions specifically for molecular glue ternary complexes may be the most effective way to fill this gap. This paper doesn’t provide the final answer, but it clearly identifies the problem and lays out a clear roadmap for future method development.

📜Title: Optimizing Molecular Glues Using Free Energy Perturbation and Cofolding Methods 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-tb29n