Table of Contents

- The LINKER model predicts specific chemical interactions between proteins and small molecules using only sequences, providing key insights for drug discovery projects that lack 3D structures.

- EffiChem uses LoRA technology to fine-tune large chemical language models and combines them with classical molecular descriptors to achieve low-cost, high-performance molecular property prediction.

- In antiviral drug prediction, XGBoost models with curated features outperform GNNs for ADME properties, while transfer learning is a more effective strategy for drug potency.

1. LINKER: Predicting Interactions from Sequences, No 3D Structure Needed

In drug discovery, we often face a problem: we have a promising compound and its target protein, but we don’t have the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex. Without a structure, optimizing the molecule is like fumbling in the dark, and many computational tools are useless.

The LINKER model addresses this old problem. It can predict the specific types of chemical interactions that might occur between a protein and a small molecule, based only on the protein’s 1D amino acid sequence and the molecule’s SMILES string.

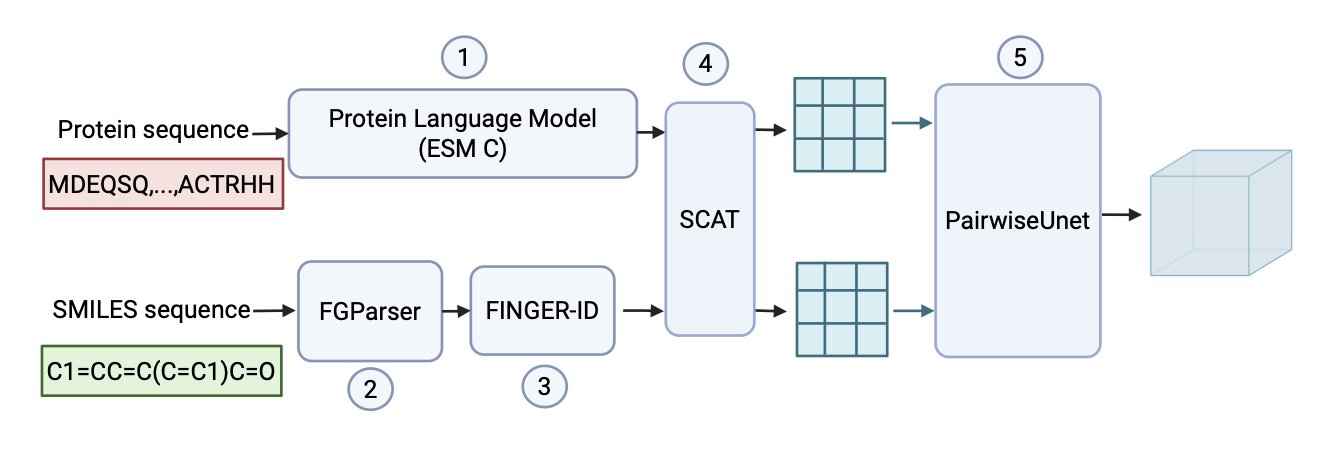

Here’s how it works

Think of it like preparing a student for an exam. First, you give them practice questions with the answers (known 3D protein-ligand structures) and let them study. They don’t just memorize that the answer to a question is A; they learn why it’s A. For instance, they see a carboxyl group and an arginine residue close together and, from the answer key (the 3D structure), learn they likely form a salt bridge. By studying thousands of these examples, they start to recognize the patterns.

LINKER’s training is like this “open-book exam.” Researchers used a large number of known 3D structures from the PDBBind database as the “answer key.” This let the model learn which amino acid residues and which small-molecule functional groups tend to form specific “chemical handshakes,” like hydrogen bonds, π-stacking, or salt bridges. This method is called “structure-supervised” learning.

Once training is complete, it’s time for the “closed-book exam.” You give LINKER a new protein sequence and a new small molecule, with no 3D structure to reference. But based on the chemical principles it learned, it can directly predict the most likely interaction patterns between them.

Why is this important?

Many previous models could predict interactions, but they usually just produced a “contact map,” telling you “this part is close to that part.” That’s somewhat useful, but not enough. As chemists, we want to know why they are close. Is it a hydrogen bond pulling them together, or a hydrophobic interaction?

LINKER provides the information chemists actually care about. It directly tells you: “This benzene ring and that tryptophan residue are forming a π-stacking interaction.” This information is actionable. You can immediately think, “If I replace the benzene ring with an aromatic ring that has an electron-donating group, maybe the interaction will be stronger.”

How well does it perform?

Researchers tested LINKER on the LP-PDBBind benchmark dataset. The results showed that its accuracy and recall in predicting interactions were higher than existing methods.

Even more convincing is that LINKER also performed well in predicting binding affinity. If a model truly understands the key chemical forces that determine binding, its combined judgment of these forces should directly correlate with the molecule’s binding strength. Although LINKER wasn’t specifically trained to predict affinity, its predictions showed a good correlation with experimentally measured affinities. This suggests the model learned real chemical principles.

For drug discovery scientists in the early stages of a project, when a crystal structure is still far off, a tool like LINKER can provide an explainable, chemistry-based model of molecular interactions. This helps us design better molecules, faster.

📜Title: Linker: Learning Interactions Between Functional Groups and Residues With Chemical Knowledge-Enhanced Reasoning and Explainability

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.03425v1

2. EffiChem: Making Large Chemical Models More Efficient with LoRA

Large Language Models (LLMs) have great potential in drug discovery, but they are massive. Pre-training models like Molformer-XL is expensive. If you had to fine-tune the entire model for every different task—like predicting toxicity or blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability—the cost and time would be prohibitive. It would be like building a new oven every time you wanted to bake a different kind of cake.

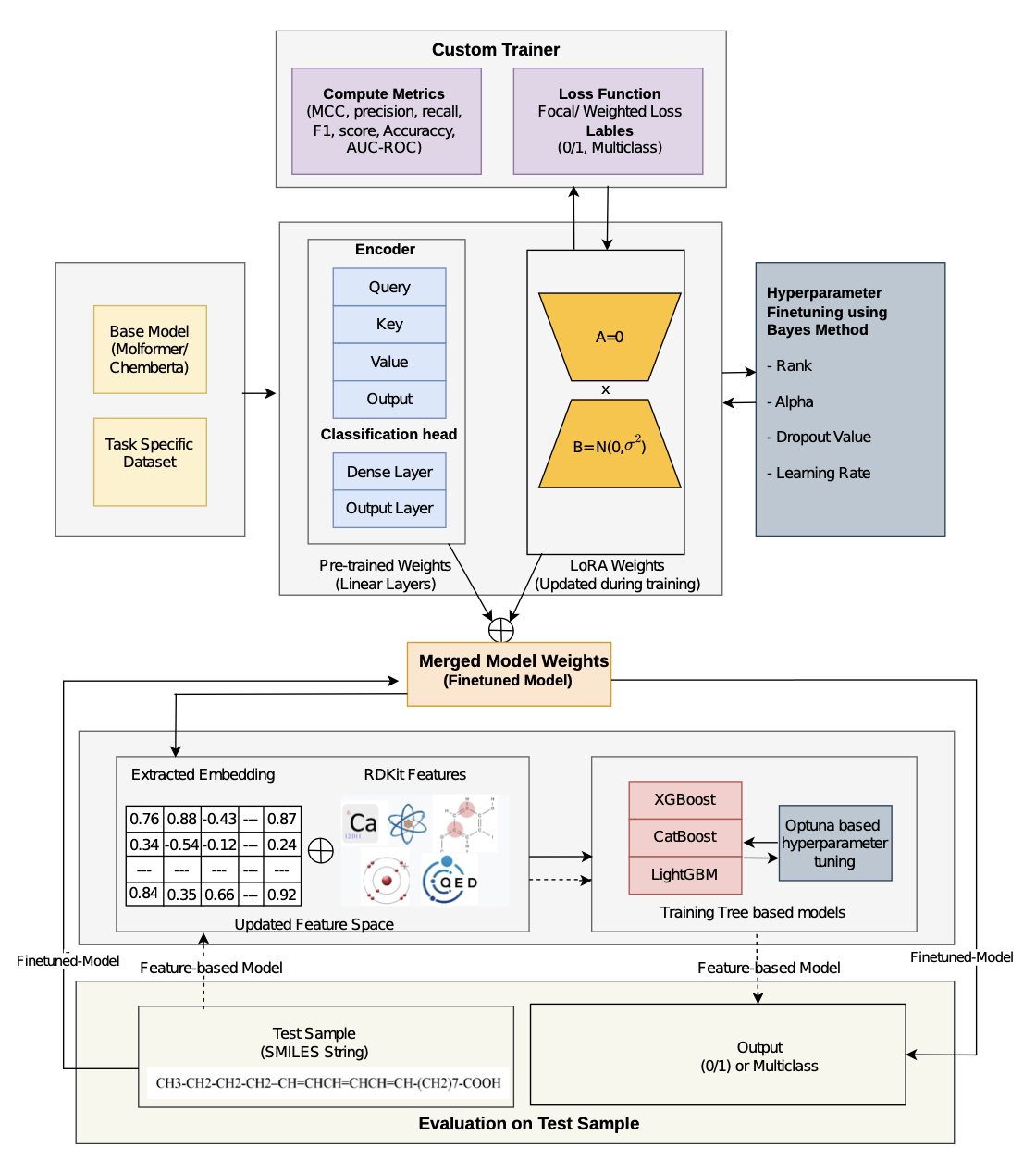

The EffiChem framework offers a solution: Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT), specifically using a technique called Low-Rank Adapters (LoRA).

The idea is to freeze the main parameters of the pre-trained large model and insert small, trainable “adapter” matrices into certain layers. When fine-tuning for a new task, you only train these adapters, which have very few parameters. This is like adding and tuning a turbocharger (the LoRA adapter) to a general-purpose engine (the pre-trained model) without modifying the engine itself. This approach reduces the number of trainable parameters and lowers computational costs. On several public datasets for tasks like toxicity and BBB permeability prediction, its AUC improved by 3-5% compared to existing models like Molformer-XL and MAMMAL.

EffiChem doesn’t completely abandon traditional methods.

The researchers take the molecular embeddings generated by the fine-tuned model and concatenate them with traditional molecular descriptors calculated by RDKit (like molecular weight or logP). This combined feature set is then fed into a classical machine learning model like XGBoost or LightGBM for the final prediction. The deep representations from the large model can capture complex structure-activity relationships, while the traditional descriptors act like a chemist’s rules of thumb—intuitive and effective. Combining them is like having an experienced expert collaborate with a young person equipped with advanced tools.

EffiChem also accounts for real-world data challenges. For example, in toxicity datasets, toxic molecules are usually in the minority, creating a class imbalance. A model could easily “get lazy” and predict all molecules as non-toxic, achieving high accuracy but providing no practical value. EffiChem addresses this using weighted loss and focal loss functions, which guide the model to pay more attention to the rare but important samples.

The model also incorporates integrated gradients for explainability analysis. It not only predicts whether a molecule is toxic but can also point out the atoms or functional groups likely responsible for the toxicity. This information can directly guide medicinal chemists in optimizing molecular structures for drug design.

EffiChem provides a practical and efficient workflow, not just a new model. It lowers the barrier to using and deploying large chemical language models, enabling smaller teams and individual researchers to leverage these tools. This can help accelerate progress across the entire field of drug discovery.

📜Title: EffiChem: Efficient Adaptation of Chemical Language Models for Molecular Property Prediction

📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-2lljt

💻Code: https://github.com/kavyagl2/Molformer_git

3. AI Drug Prediction in Practice: XGBoost for ADME, Transfer Learning for Potency

A report from the ASAP-Polaris-OpenADMET antiviral drug challenge highlights the successful application of two different strategies. This reflects a common choice in computer-aided drug design (CADD): rely on expert knowledge or leverage deep learning.

ADME Prediction: Experience-Driven Feature Engineering

ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) prediction aims to assess a molecule’s fundamental drug-like properties, such as water solubility and metabolic stability.

The researchers started with feature engineering, carefully selecting 55 molecular descriptors like molecular weight, LogP (lipophilicity), and Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA). These features represent decades of medicinal chemistry knowledge.

They then fed these features into an XGBoost model, a gradient-boosted tree model known for its excellent performance on tabular data. In 4 out of 5 ADME prediction tasks, this combination outperformed a Graph Neural Network (GNN) that learned directly from molecular structures.

GNNs can automatically learn features from a molecule’s graph structure, but they need a lot of high-quality data to understand chemical rules. If the dataset is small or covers a narrow chemical space, the features a GNN learns might not be as effective as the descriptors summarized by human experts.

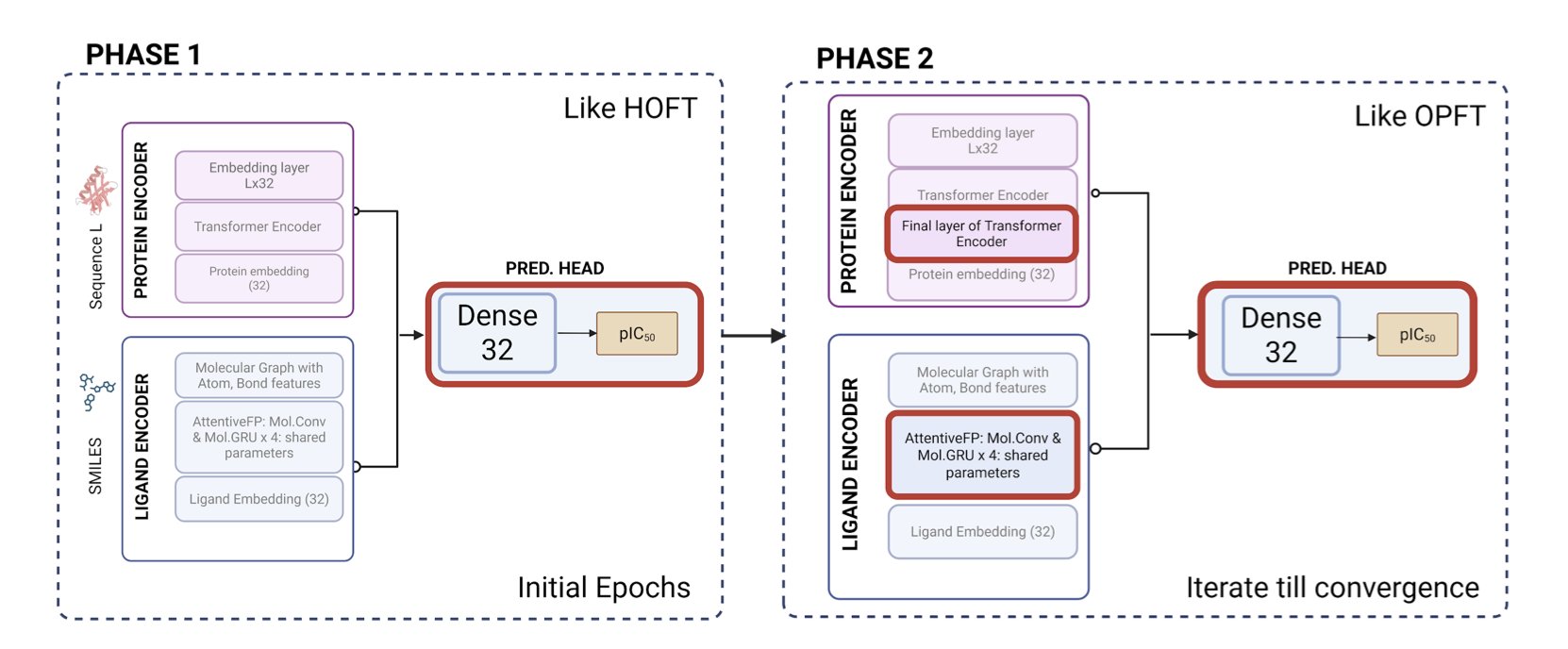

Drug Potency Prediction: Big-Data Pre-trained Models

Predicting drug potency is more complex. It requires a precise understanding of how a drug molecule interacts with its target protein, and “specificity” is key.

For this task, the researchers used a fusion model that combined an AttentiveFP-GNN and a Transformer. GNNs are good at understanding a molecule’s local chemical environment, while Transformers can capture long-range interactions.

The key to this strategy was “transfer learning.” The model wasn’t trained directly on the small challenge dataset. Instead, it was first “pre-trained” on a massive amount of protein-ligand data from the ChEMBL database.

This process is like having a student read all the relevant books in the library before an exam. They master the general principles of chemical and biological interactions. Then, when they are “fine-tuned” on the specific task from the challenge, the model learns more efficiently and effectively. Ultimately, this model achieved a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of about 0.79 in the blind test, which is a good result.

This work shows that there is no one-size-fits-all model. In CADD, you should choose your tools based on the problem. For relatively well-understood problems like ADME, feature engineering based on expert knowledge combined with classical models can be a shortcut. But for complex problems like target-specific binding, pre-training complex deep learning models on massive datasets is a more effective path.

📜Title: Experiments with data-augmented modeling of ADME and Potency endpoints in the ASAP-Polaris-OpenADMET Antiviral Challenge

📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-1tb2m

Code: https://github.com/apalania/Polaris_ASAP-Challenge-2025