Table of Contents

- The BALD-GFlowNet framework switches active learning from “screening” to “generating,” freeing it from reliance on pool size and offering a new way to screen massive molecular libraries.

- Designing molecules with AI is the first step. Teaching AI the logic of chemical synthesis is what makes it practical.

- This study uses machine learning to combine a new drug’s molecular information with real-world patient data, trying to predict its effectiveness before clinical trials.

1. GFlowNet Powers Active Learning, Speeding Up Virtual Screening 2.5x

One of the central challenges in computer-aided drug design (CADD) is finding promising hit compounds efficiently within the vastness of chemical space. How vast? An estimate of 10^60 is probably conservative.

Traditional virtual screening is like looking for a needle in a haystack. To improve efficiency, we use active learning. The logic is simple: instead of testing randomly, we ask the model which molecule it is “most unsure” about and test that one. This makes the most of every expensive experiment or computation.

Bayesian Active Learning by Disagreement (BALD) is a classic algorithm in this field. It works by scoring every molecule in a candidate pool. A higher score means the model has greater disagreement, or uncertainty, about its prediction. We then select the highest-scoring molecule for the next round of validation.

This method works well, but it has a critical weakness: it needs to score every molecule in the pool. When your library grows from millions to tens of millions or even billions of molecules, this scoring process goes from a feature to a disaster. The computational cost becomes prohibitive. It’s like trying to hire a top programmer by making everyone in the city take a coding test. It’s too inefficient.

The BALD-GFlowNet framework proposed in this paper is designed to solve this problem. Why do we have to “pick” from a fixed pool? Can we directly “create” the molecule the model most wants to see?

This is where Generative Flow Networks (GFlowNets) come in. You can think of a GFlowNet as a molecule “generator.” We don’t give it a fixed library. Instead, we give it a reward function, which in this case is the BALD uncertainty score. Its task then becomes generating a molecule that makes this BALD score as high as possible.

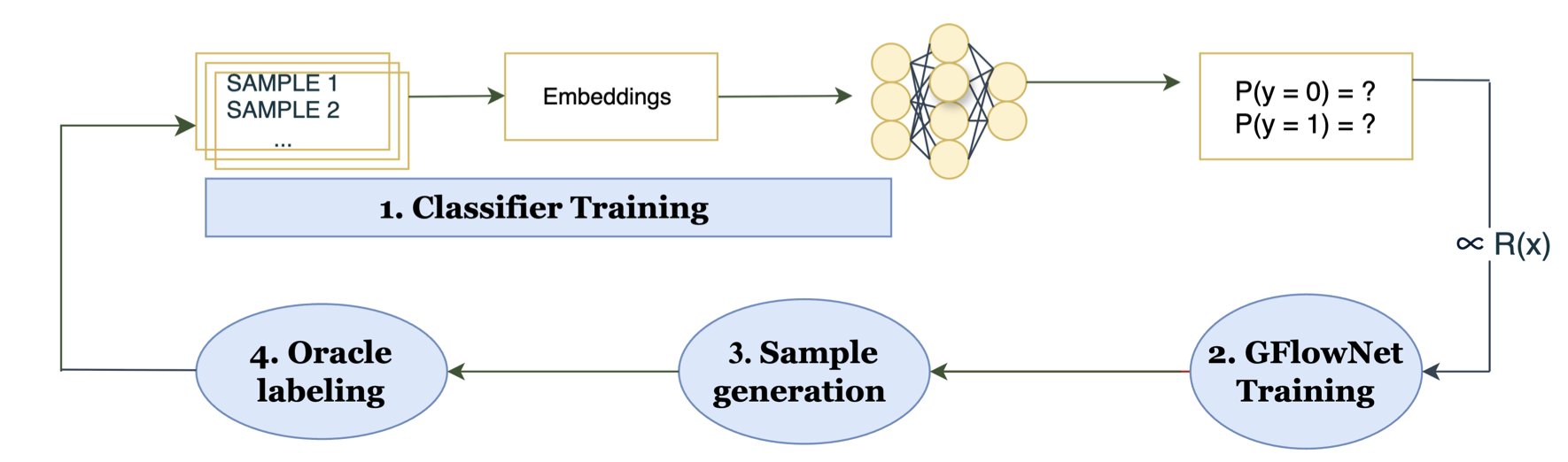

The workflow is roughly as follows: 1. First, we train an initial prediction model on a small set of known data. 2. Then, we train the GFlowNet to learn a path (e.g., adding atoms and bonds step-by-step) to construct a molecule that earns a high BALD reward. 3. The GFlowNet directly generates a batch of high-uncertainty molecules. We take these molecules and label them (for instance, by getting their activity data through experiments or high-precision calculations). 4. We use this new, high-quality data to update our prediction model, making it more accurate. And the cycle repeats.

Throughout this process, we completely bypass iterating over the entire 50-million-molecule library. The computational cost is only related to the molecule generation process, not the size of the library. It’s like hiring: instead of a city-wide audition, you have a top headhunter recommend the most suitable candidates directly to you.

The researchers tested this idea on a real-world drug discovery task: finding inhibitors for the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) target. The results were impressive. On a 50-million-molecule library, BALD-GFlowNet was 2.5 times more efficient than traditional BALD, and the active molecules it found were comparable in quality.

This isn’t just about speed. During the generation process, GFlowNet also ensures the chemical validity and structural diversity of the molecules. This is critical for drug discovery, as we don’t want the model to generate a pile of bizarre structures that are impossible to synthesize.

The real value of this work is that it provides a feasible and efficient path for handling extremely large molecular libraries. Moving from “screening in a pool” to “generating on demand” could be a major step forward for active learning in drug discovery.

📜Title: Why Pool When You Can Flow? Active Learning with GFlowNets 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.00704

2. AI Drug Design: Cool Molecules Are Useless If You Can’t Make Them

Generative AI in pharma has an elephant in the room—a topic everyone sees but pretends not to: can the molecules you generate actually be synthesized?

Many generative models are like artists with infinite inspiration who never set foot in a kitchen. They can “draw” all sorts of novel molecular structures, but if you hand them to a synthetic chemist, they’ll likely just shake their head. Most of these creations can’t be made in the real world. This is one of the biggest hurdles between computation and experimentation in AI drug discovery.

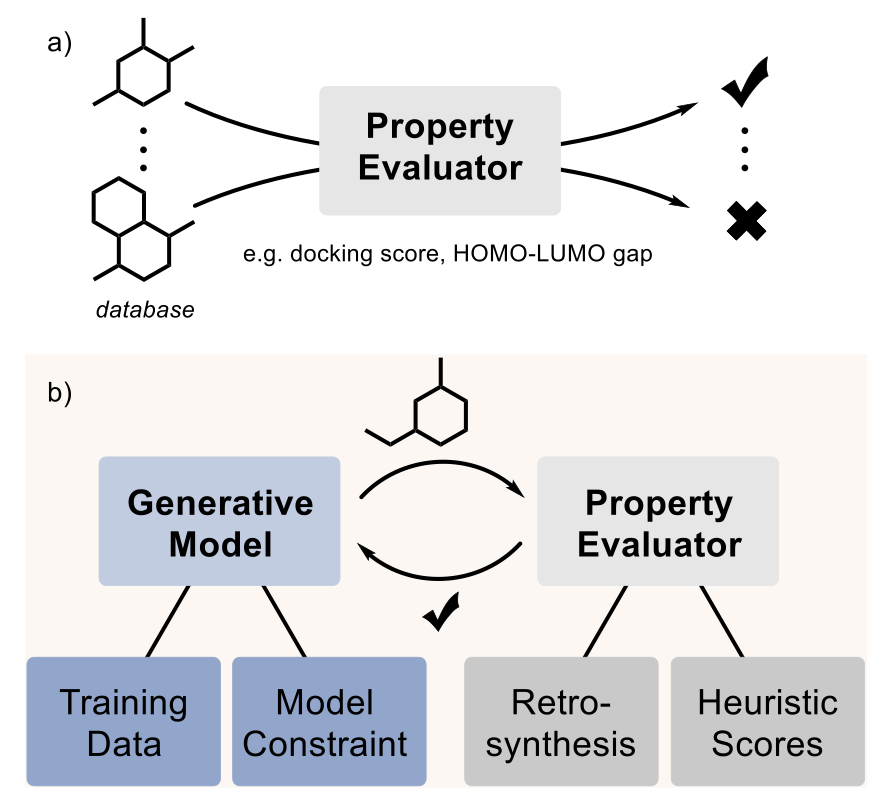

Fortunately, people are starting to confront this elephant. This paper reviews several of the main strategies the industry is using to tackle the problem.

The first method is the most direct: start with good ingredients. If you want the model to learn to cook, you can’t just show it pictures of food; you have to give it recipes. Researchers have compiled specialized datasets, like the MOSES subset filtered from the ZINC database, which contains molecules that are relatively easy to synthesize. Models trained on this data naturally produce more synthesizable molecules.

The second approach is like putting the model in a “straitjacket,” but one designed by chemists with clear rules. It involves pre-defining a set of reliable chemical reaction templates and commercially available building blocks. The model can only create within this framework. Every step of generation corresponds to a real chemical reaction. The benefit is that the generated molecules are 100% synthesizable; you even get a list of suppliers for the raw materials.

The third method is to give the model a “navigator.” As the model explores chemical space, every time it comes up with a new structural fragment, the navigator immediately provides a score indicating its synthetic difficulty. This score comes from what are called “heuristic proxies,” like the commonly used SAscore. It works by analyzing how many common, known chemical fragments a molecule can be broken down into. A lower score suggests it’s more like a “normal” molecule found in databases like PubChem and is likely easier to synthesize. It’s a shortcut for quick assessment.

Of course, none of these methods are perfect. The biggest problem right now is that everyone is doing their own thing, with no recognized benchmark to judge which method is better. Company A might claim its model has a high generation rate, while Company B boasts about the novelty of its molecules, but with no uniform standard, it’s hard to make direct comparisons. The authors call for a standardized computational evaluation process for the industry. For example, everyone could run their generated molecules through an open-source retrosynthesis tool like AiZynthFinder to see which ones can find a reliable synthetic route faster.

Ultimately, computation is just computation. What really matters is whether you can make the compound in a fume hood and test its activity. There is still very little work on this front because it’s so expensive. But there are success stories. The paper mentions cases where generative models were used to discover new KRAS inhibitors and antibiotics, proving that this path is viable.

What’s next? Researchers are thinking bigger. For example, they want to train models to learn complete, multi-step experimental procedures, not just single reactions. Or, they could build “self-driving laboratories” where robots handle the grunt work of synthesis and testing, fully closing the loop from model output to experimental validation.

📜Title: The elephant in the lab: Synthesizability in generative small-molecule design 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-1lcpq

3. AI Predicts New Drug Efficacy: From Molecular Structure to Clinical Outcomes

In drug development, we are always looking for models that can predict success. Every year, countless candidate molecules fail at the clinical trial finish line after enormous investments of time and money. If there were a way to roughly estimate a molecule’s effect on real patients while it’s still in the lab, it would change the game. This paper is an attempt in that direction.

The core idea is to create a “drug map.” This map isn’t based on geography but on the properties of drugs. The researchers tried two ways of drawing this map.

The first is a map based on chemical structure. They used SMILES strings, which are a way of representing molecular structures in a line of text. By analyzing these strings with an algorithm, they could place structurally similar molecules close to each other on the map. It’s like classifying cars by their engine and chassis models—similar structures end up clustered together.

The second is a map based on biological function. For this, they used the KEGG database, which documents the complex relationships between drugs, targets, proteins, and biological pathways. The map created with this method groups drugs with similar mechanisms of action. This is like classifying cars by their purpose—sports cars in one group, trucks in another, regardless of their specific engine models.

After creating the maps, the next step was the most critical: how to use them for prediction?

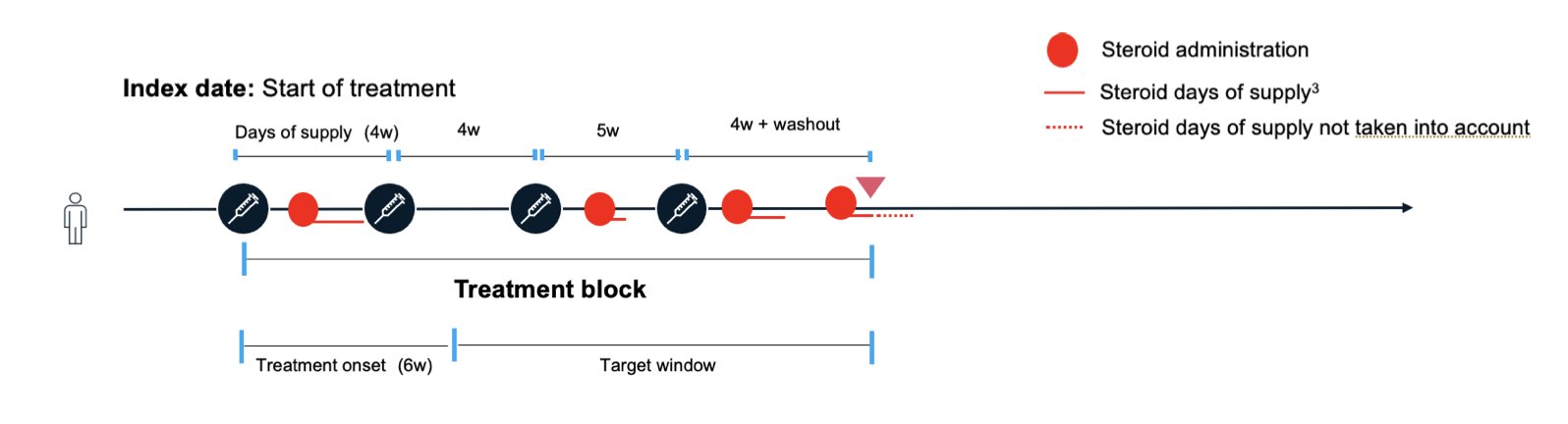

The researchers obtained real-world data from patients with ulcerative colitis. This data included which known drugs the patients used and the treatment outcomes. They then overlaid this information onto the “drug maps.”

Now, when a brand-new, untested drug molecule comes along, they first find its coordinates on the map based on its chemical structure or expected biological function. Then, the model looks at the “neighbors” around these new coordinates—the known drugs. If the neighbors generally have good efficacy, the model predicts that the new drug is also likely to be effective. If the neighbors have mediocre results, the new drug’s prospects may not be as bright.

The results showed that this method isn’t a silver bullet. Its predictive power largely depends on how similar the new drug is to known drugs. If a new drug lands in an “uncharted territory” on the map, with no known drugs nearby for reference, the model’s prediction is about as good as a random guess. But if it lands in a cluster of known effective drugs, the prediction is much more accurate.

The value of this work isn’t that it provides a ready-to-use prediction tool, but that it establishes a flexible framework. You can swap out any of its components. For example, you could use more advanced graph neural networks to generate molecular “fingerprints” or use more complex causal inference models to analyze the real-world data.

This paints a picture of what’s possible: in the future, before deciding which candidate molecule to advance to expensive clinical trials, we could first run it through a method like this for a “virtual screening.” We could calculate its “predicted success rate” in a real patient population. This can’t replace clinical trials, but it can help us focus our valuable resources on the most promising candidates. Even a few percentage points of improvement in our success rate would be a huge gain for the entire industry.

📜Title: Predicting Effect of Novel Treatments Using Molecular Pathways and Real–World Data 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.07204v1