Table of Contents

- SAGERank is an inductive learning framework based on graph neural networks. It outperforms existing methods in antibody-antigen docking scoring and epitope prediction and generalizes well from small datasets.

- VECTOR+ offers a practical framework for low-data drug discovery using property-enhanced contrastive learning, generating novel candidate molecules with better docking scores.

- For predicting cyclic peptide membrane permeability, graph neural networks (especially DMPNN) perform best. But a real breakthrough requires future models to incorporate the dynamic 3D structure of molecules.

1. SAGERank: Graph Neural Networks Reinvent Antibody-Antigen Docking

In computational structural biology, particularly in antibody drug development, predicting protein-protein interactions (PPIs) is hard. We run molecular docking software, get a huge list of possible binding poses, and then face a core question: which one is correct? Traditional scoring functions like Rosetta or FoldX each have their strengths, but the results are often unsatisfying.

The SAGERank model offers a new option, using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to solve this problem.

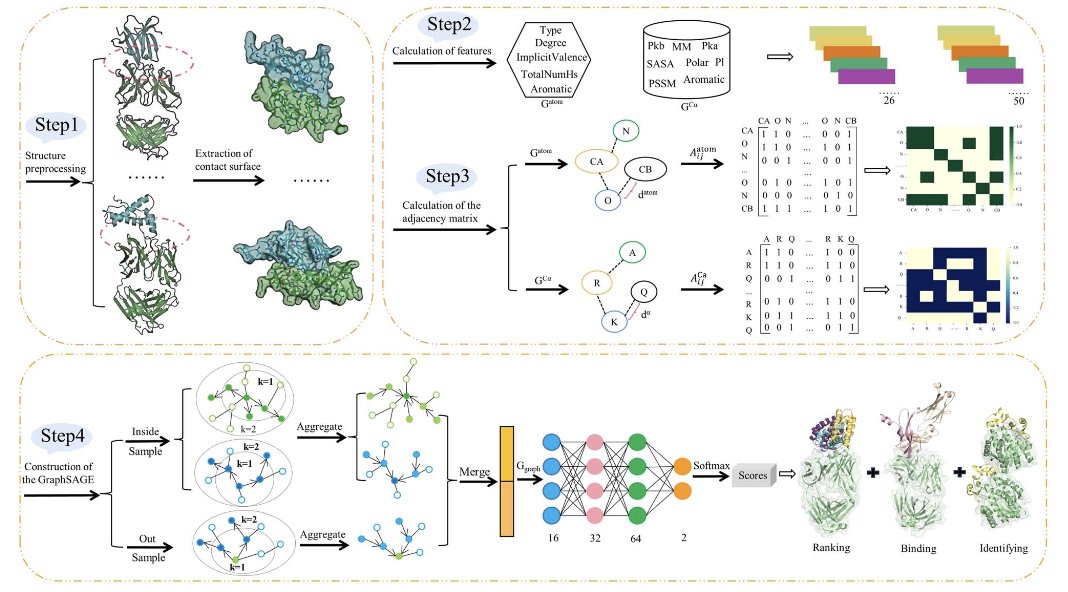

Here’s how it works.

First, the researchers treat the antibody-antigen interface as an atom-level graph. Each node in the graph is an atom, and the connections represent their relationships. This step is key because it transforms a complex 3D structural problem into a data format that graph networks are good at handling.

SAGERank’s core technology is GraphSAGE (Graph Sample and Aggregate). The power of this algorithm lies in its “inductive learning” capability. Many traditional graph learning models are “transductive,” meaning they can only process nodes they saw during training. In other words, if you train a model on dataset A, it can only make predictions about things in A. If a new protein B comes along, it can’t handle it.

But inductive learning is different. GraphSAGE learns a representation for each node by aggregating information from its neighbors. It learns a set of general “aggregation rules.” So, even when it encounters a completely new, unseen protein complex, it can apply these rules to understand and predict it. This is important for drug discovery, where we are always dealing with new targets and molecules.

What about the results? The researchers trained SAGERank on a dataset of 287 antibody-antigen complexes. In the world of deep learning, this is a very small dataset. But thanks to its inductive learning ability, it performed well. In docking pose ranking tests, SAGERank’s hit rate and success rate were significantly better than established tools like Zrank, Pisa, FoldX, and Rosetta. This means that if you use SAGERank for screening, you are more likely to find the correct, near-native pose among the top few results.

The authors also applied SAGERank to other areas: 1. T-cell receptor (TCR) recognition: It handled the recognition of TCR-pMHC complexes well, proving the model’s generalization ability isn’t limited to antibodies. 2. Epitope prediction: It accurately identified the key binding regions on the antigen. This is a useful function for antibody design and vaccine development. 3. Molecular glues: The researchers even tested it on a dataset of ternary complexes mediated by molecular glues. The results showed SAGERank has the potential to distinguish these complex interactions involving small molecules, expanding its application from biologics to the small-molecule field.

Overall, SAGERank provides a powerful and efficient tool for PPI prediction and scoring. Its main strength is using an inductive graph neural network to solve the generalization problem with small datasets. For R&D scientists, this means another reliable computational tool to aid in antibody design and structural analysis. The design philosophy behind it also offers a good reference for solving other molecular recognition problems.

📜Title: SAGERank: Inductive Learning of Protein–Protein Interaction from Antibody–Antigen Recognition 📜Paper: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2025/sc/d5sc03707g 💻Code: https://github.com/sunchuance/SAGERank

2. Generating New Drugs with Little Data? VECTOR+ Uses Contrastive Learning

In drug discovery, we often face a dilemma: we have only a few dozen hit compounds with decent activity. The dataset is too small to train a generative AI model to find better molecular structures. It’s like asking a chef to prepare a grand feast with only a pinch of salt and pepper. Most generative models need thousands of data points to learn anything.

The VECTOR+ framework in this paper is designed to solve this practical “low-data” problem. If you can’t win with quantity, you teach the model to focus on quality.

How does it work?

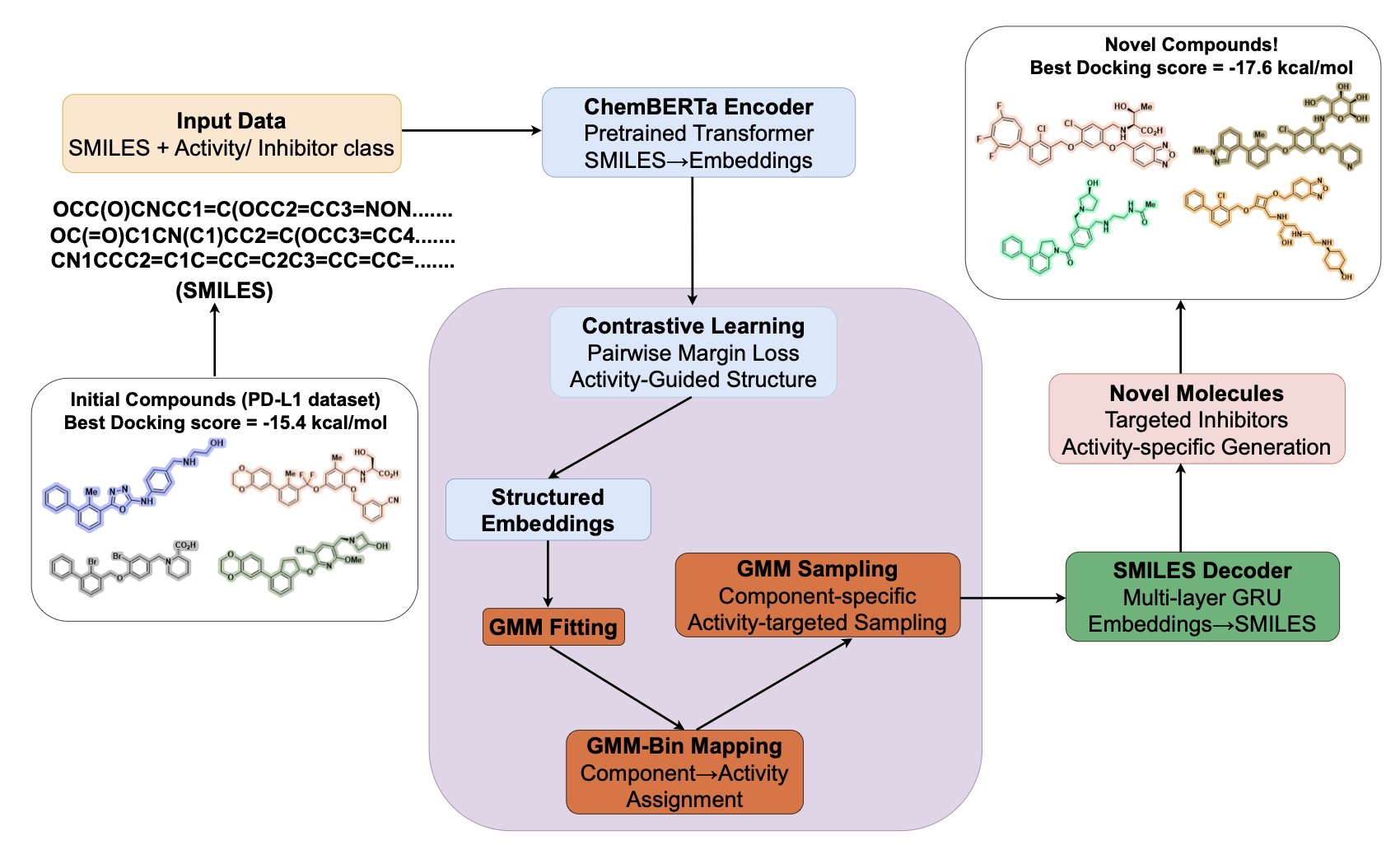

The process has two steps.

First, it builds a meaningful chemical “map,” known as the Latent Space. A traditional autoencoder learns to compress a molecule into a string of numbers and then reconstruct it, focusing on making it look similar. VECTOR+ does something different. It uses Contrastive Learning.

You can think of it this way: the model looks at three molecules at once. An “anchor” molecule, a “positive” sample that has similar properties (e.g., both are highly active), and a “negative” sample with different properties (e.g., poor activity). The model’s goal is simple: on its internal map, it pulls the anchor and the positive sample closer together while pushing the anchor and the negative sample farther apart.

By repeating this process, the latent space is no longer organized simply by chemical structural similarity. It gets re-partitioned based on the pharmacological property we care about, like inhibitory activity against PD-L1. Molecules with good activity cluster together, forming “advantaged regions.” This process doesn’t require massive amounts of data because it focuses on the “relative relationships” between molecules, not the “absolute coordinates” of each one.

The second step is to create new molecules from these advantaged regions. Once the map is drawn, the researchers use a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to locate the clusters of the most active molecules. This is like finding “treasure spots” on the map. The model then samples new molecular coordinates near these spots and uses a decoder to translate these coordinates into new chemical structures.

Does this method actually work?

The researchers validated it on two targets: PD-L1, a popular target in immuno-oncology, and a receptor kinase.

For PD-L1, they even curated and released a dataset of 296 small-molecule inhibitors, which is a contribution in itself. The experimental results were practical: the new molecules generated by VECTOR+ were not only chemically distinct from those in the training set (high novelty) but also highly synthesizable. Most importantly, their molecular docking scores were higher than those of known inhibitors in the database.

This shows the AI model wasn’t just imitating. It was exploring more promising chemical space based on what it already knew. This is exactly the role we want AI to play in drug discovery: a creative partner that can provide high-quality, novel ideas.

They also compared VECTOR+ with well-known generative models like JT-VAE and MolGPT. VECTOR+ performed better across metrics like docking score, novelty, and uniqueness.

As a research scientist, I find this strategy very practical. In the early stages of a project, data is what we lack most. A method like VECTOR+—which builds a chemical space by reinforcing property differences between molecules instead of relying on huge datasets—offers a viable solution for AI-powered early drug discovery. It doesn’t generate a pile of random, unsynthesizable structures, but rather valuable candidate molecules that can directly inspire the next round of compound design and synthesis.

📜Title: Valid Property-Enhanced Contrastive Learning for Targeted Optimization & Resampling for Novel Drug Design 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.00684v1

3. AI Predicts Cyclic Peptide Permeability: DMPNN Wins, but 3D Structure is Key

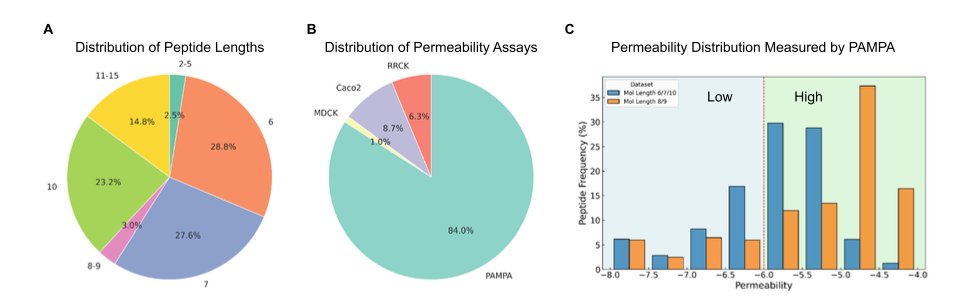

Cyclic peptides, a class of “beyond Rule of 5” (bRo5) molecules, are a tough nut to crack, especially when it comes to cell membrane permeability. We all want computational models that can accurately predict which molecules will get into cells and which will be blocked. This could save a lot of time and money in drug design. Liu et al. systematically compared 13 mainstream machine learning methods to see which one is the “king” of predicting cyclic peptide permeability.

The study’s conclusion is clear: graph-based methods, particularly the Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN), perform best. This isn’t surprising. To a chemist, a molecule is a graph of atoms and bonds. Models like DMPNN learn directly on the molecular graph, allowing them to understand atomic connectivity and spatial arrangement, rather than just processing a text string (SMILES). The model can see what an atom’s local neighborhood looks like (local features) and also sense the influence of a functional group on the other side of the ring (long-range dependencies). This is critical for large, flexible molecules like cyclic peptides.

The study also offers practical advice: directly predicting the numerical value of permeability (regression) is much better than simply classifying it as “high” or “low” (classification). In drug optimization, we need to know if a new molecule’s permeability improved by 10% or 10-fold; a vague “better” label is not useful. Regression models provide quantitative feedback, which is the information we need to iterate on molecular structures.

An interesting finding concerns data splitting. In machine learning, we usually consider “Scaffold Split” to be the gold standard for evaluating a model’s generalization ability, more rigorous than a “Random Split.” It ensures that the molecular scaffolds in the training and test sets are completely different, preventing the model from just “memorizing” answers for specific scaffolds. But in this study, random splitting actually produced better results. This sounds counterintuitive, but it makes sense on reflection. Current cyclic peptide permeability datasets are not very large and have limited chemical diversity. Forcing a scaffold split might prevent the model from ever seeing certain types of chemical structures during training, which hurts its ability to generalize. This reminds us that with limited data, showing the model as many diverse chemical “examples” as possible might be more important than using a strict splitting method.

However, the most important insight from this work points to the “Achilles’ heel” of all current models: they all ignore the molecule’s three-dimensional (3D) and even four-dimensional (4D, i.e., dynamic) structure.

A cyclic peptide is not a rigid block; it’s like a flexible keychain. It adopts one conformation in an aqueous solution and another as it approaches the hydrophobic cell membrane. This “chameleon-like” conformational change is precisely what determines whether it can cross the membrane. Current models are based on 2D molecular graphs. This is like trying to judge if a house is livable by looking only at its floor plan—you lose the most critical spatial information.

The researchers tried to improve performance by adding descriptors like logP or Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) as auxiliary tasks, but the effect was minimal. This suggests that simple physicochemical properties are not enough to capture the complexity of the permeation process. For future models to make a qualitative leap, they must be able to process and understand the 3D conformational ensembles of molecules, and even their dynamic changes during membrane transit. We need a high-quality dataset containing the dynamic conformations of cyclic peptides. That is the next engine that will drive this field forward.

📜Title: Systematic Benchmarking of 13 AI Methods for Predicting Cyclic Peptide Membrane Permeability 📜Paper: https://jcheminf.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13321-025-01083-4