Table of Contents

- MolSculptor combines the generative power of diffusion models with the optimization strength of evolutionary algorithms. This creates a new way to design multi-target, highly selective molecules without needing target-specific training.

- OTMol uses optimal transport theory to solve key problems in molecular alignment, like inconsistent atom ordering and chirality flips, offering a more robust and chemically meaningful framework.

- PertFormer is a multiomics foundation model that can predict the consequences of gene perturbations in a “zero-shot” manner, speeding up biological discovery and the identification of new drug targets.

1. MolSculptor: Sculpting Multi-Target Drugs with a Diffusion-Evolution Model

In drug development, designing a molecule that hits just one target is already hard. Designing one that hits targets A and B while avoiding the structurally similar target C is exponentially harder. This is the central challenge of multi-target drug design and high-selectivity inhibitors.

A new computational framework called MolSculptor offers a way to solve this problem.

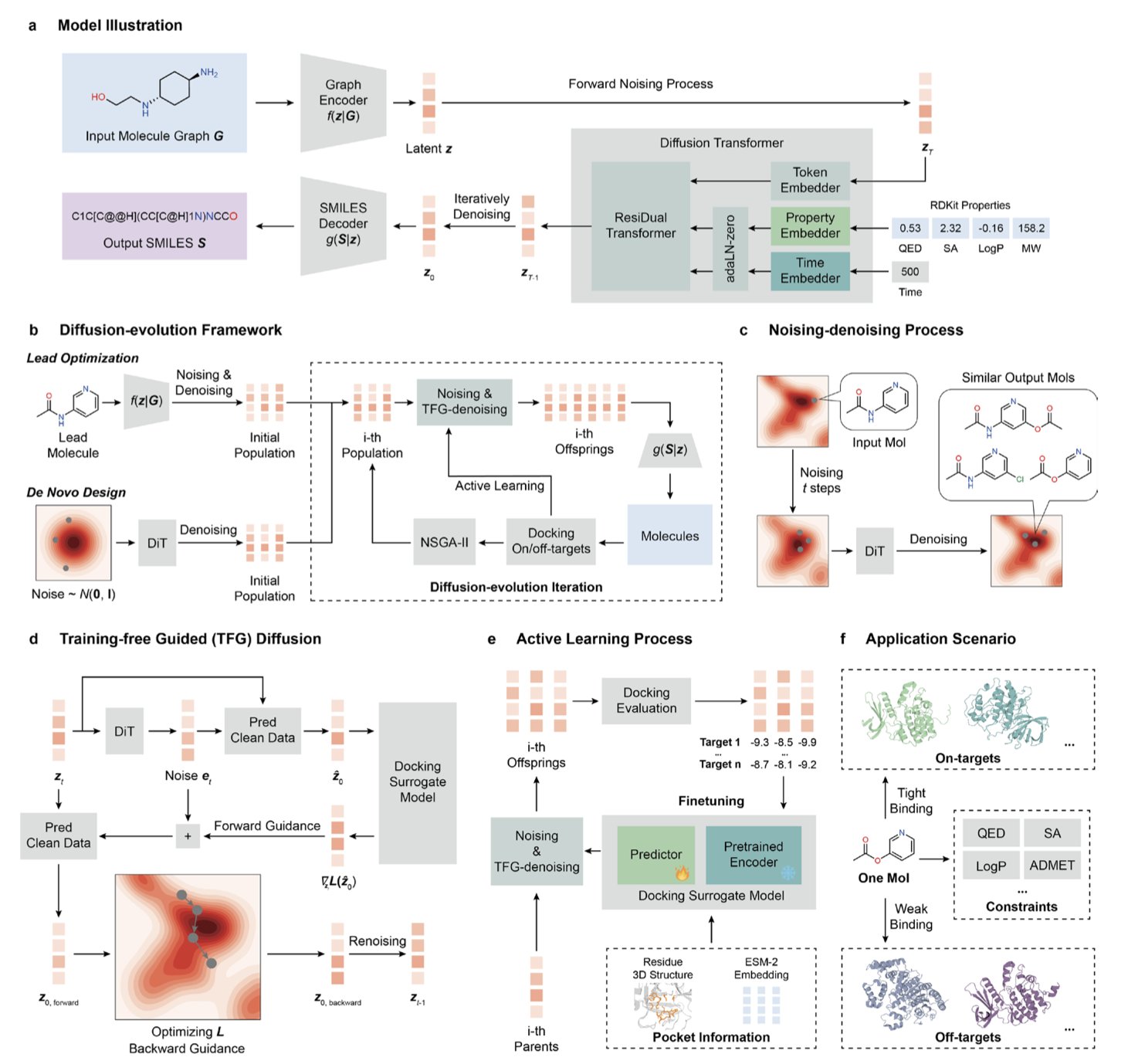

A Diffusion Model for the Hammer, an Evolutionary Algorithm for the Chisel

Think of the process like a sculptor at work. The diffusion model is like a magic hammer. It first “smashes” a molecular structure into a random cloud of atoms (noising) and then learns how to “rebuild” a valid molecule from that cloud (denoising). This process of breaking and rebuilding introduces the randomness and possibility needed for creativity.

But a hammer alone isn’t enough; you also need a precise eye and a chisel to guide the work. This is where the evolutionary algorithm and active learning come in. After each molecule is generated, a surrogate model quickly evaluates its performance: How well does it bind to targets A and B? Does it bind to target C? What are its drug-like properties?

These scores act like the sculptor’s judgment. Molecules that perform well are kept for the next round of “sculpting,” while poor performers are discarded. Through repeated cycles of “generate-evaluate-select,” the molecular structure is progressively optimized until it meets all the complex constraints.

The Biggest Advantage: Freedom from Training Data Dependence

Traditional AI drug discovery models usually require extensive training on data specific to a particular target. If the target is new or has very little known active molecule data, these models are useless.

MolSculptor gets around this bottleneck. It doesn’t need to know in advance which molecules work for the target. Instead, during its “evolution,” it dynamically builds a surrogate model with active learning to predict affinity. As long as you can provide the 3D structure of the targets, MolSculptor can theoretically design molecules for any combination. This is highly valuable for exploring entirely new biological targets.

One Tool, Two Uses

The framework’s flexibility is also clear from its two modes of operation:

- De Novo Design: When you have one or more targets but no starting molecule, MolSculptor can generate completely new molecular scaffolds with the desired affinity and selectivity from scratch.

- Lead Optimization: When you already have a decent molecule, but it lacks selectivity or has other flaws, you can use it as a starting point. MolSculptor will then “fine-tune” it to improve the target properties while preserving its core structure.

Case studies in the paper demonstrate its effectiveness. In tasks for designing dual-target and high-selectivity inhibitors, molecules generated by MolSculptor achieved better docking scores than existing methods. It was even able to find molecular solutions for selective binding between two proteins with highly similar pockets.

Future Directions

Currently, MolSculptor relies mainly on docking scores to evaluate affinity. But its modular design allows for future expansion. It would be straightforward to integrate more accurate physics-based calculation methods, like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), or models that predict ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties.

This framework is not a black box. It’s an open platform that allows us to explore and sculpt ideal drug molecules in the vast chemical space more efficiently.

📜Title: MolSculptor: An Adaptive Diffusion-Evolution Framework Enabling Generative Drug Design for Multi-Target Affinity and Selectivity 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-v4758-v2 💻Code: https://github.com/egg5154/MolSculptor

2. OTMol: Redefining Molecular Alignment with Optimal Transport

In drug discovery, comparing molecular structures is fundamental to our daily work. We want to know how similar two molecules are, how a ligand binds to different protein conformations, or what the preferred conformations of a flexible molecule are. On the surface, this seems like a simple geometry problem: overlay two molecules and calculate how well they overlap.

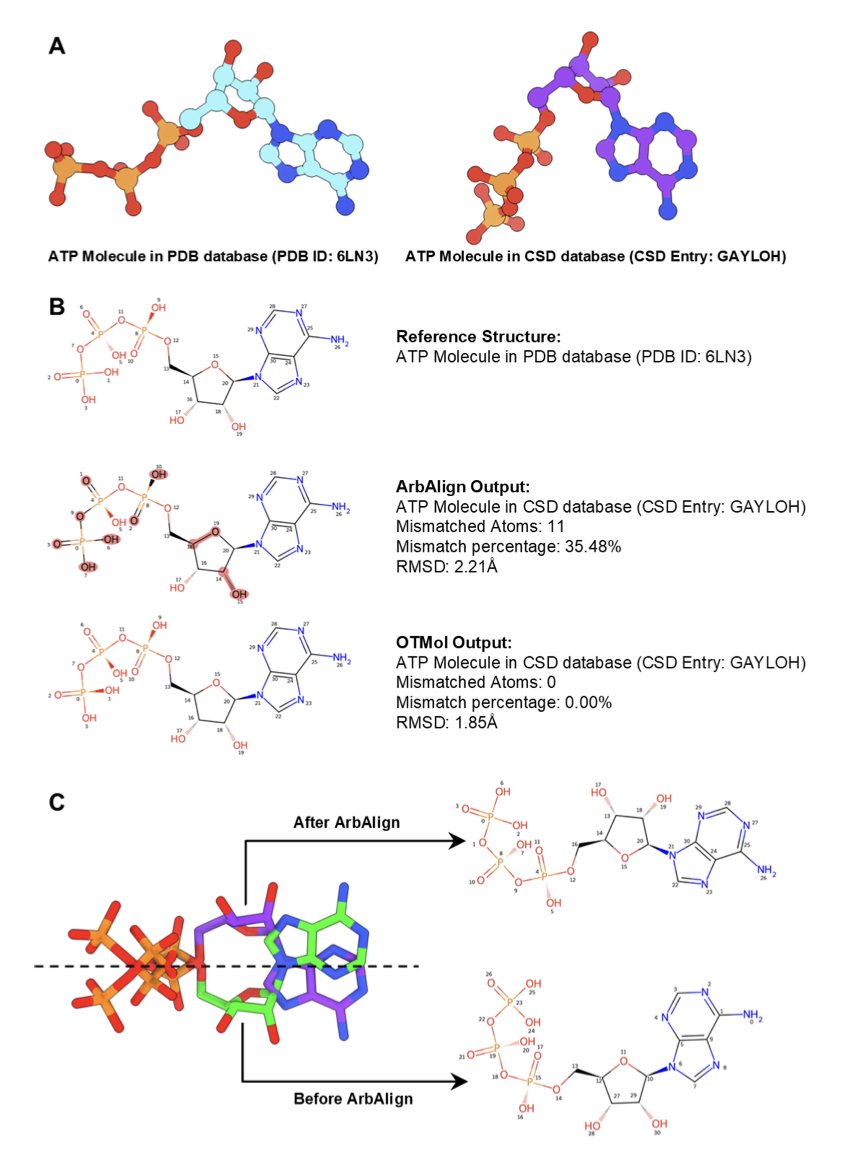

The traditional gold standard is the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD). This method is direct: it calculates the average distance between two sets of atomic coordinates. But it has a fatal flaw: RMSD only cares about spatial position; it doesn’t understand chemistry. It treats atoms as undifferentiated points, matching them if they are close. This leads to two classic problems. First, atom ordering. Numbering the atoms of the same molecule differently can produce vastly different RMSD results. Second, chemical plausibility. To get a mathematically “good” low RMSD, an algorithm might flip a chiral center or match a benzene ring to a cyclohexane. To a chemist, such a match is nonsense.

The OTMol method proposed in this paper tries to solve this old problem from a new angle. Its core idea comes from optimal transport (OT) theory. You can think of optimal transport as a “sand-moving” problem. Imagine you have two piles of sand with different shapes (representing two molecular conformations). Optimal transport finds the most efficient way to move the first pile into the shape of the second, minimizing the total “transport cost” (like distance multiplied by the amount of sand).

OTMol’s cleverness lies in how it defines this “transport cost.” It’s not just the Euclidean distance between atoms. The method frames molecular alignment as a “fused supervised Gromov-Wasserstein” (fsGW) problem. This complex term describes something that is chemically intuitive: it looks not only at the distance between atom A and atom B but also at the similarity of their respective “neighborhoods.” In other words, atoms bonded to atom A in molecule 1 should be matched to atoms bonded to atom B in molecule 2. This way, the algorithm is no longer just overlaying coordinates but comparing the internal connectivity maps of the two molecules.

The direct benefit is that we no longer need to manually define a complex cost function to tell the algorithm “don’t move this, don’t flip that.” By learning the molecule’s intrinsic geometric and topological information, the algorithm figures out the most reasonable match on its own. As a result, OTMol naturally preserves chemical bond connectivity and the configuration of chiral centers while aligning molecules. This is the chemically meaningful alignment we want.

The researchers validated this method on a series of complex molecules, including the highly flexible ATP, the classic drug Imatinib, lipids, peptides, and even water clusters. In these systems, OTMol consistently outperformed top existing methods like ArbAlign in both accuracy and speed. Its advantage is particularly clear when dealing with large and flexible molecules, because it guarantees a one-to-one correspondence between atoms, avoiding mismatched alignments.

So, OTMol provides a more reliable tool for molecular comparison, which means more accurate virtual screening results, more trustworthy conformational analysis, and a deeper understanding of structure-activity relationships.

📜Title: OTMol: Robust Molecular Structure Comparison via Optimal Transport 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.01550v1

3. PertFormer: Predicting Cell Fate Zero-Shot, AI Accelerates New Drug Target Discovery

A central question in drug discovery is: what happens to a cell if we knock out a gene or activate a protein? Understanding this could lead to the next new drug target. Traditionally, we could only find out through slow and laborious wet-lab experiments, one at a time. A computational model called PertFormer shows us the possibility of using “computation” to replace “experimentation.”

How Does It Work?

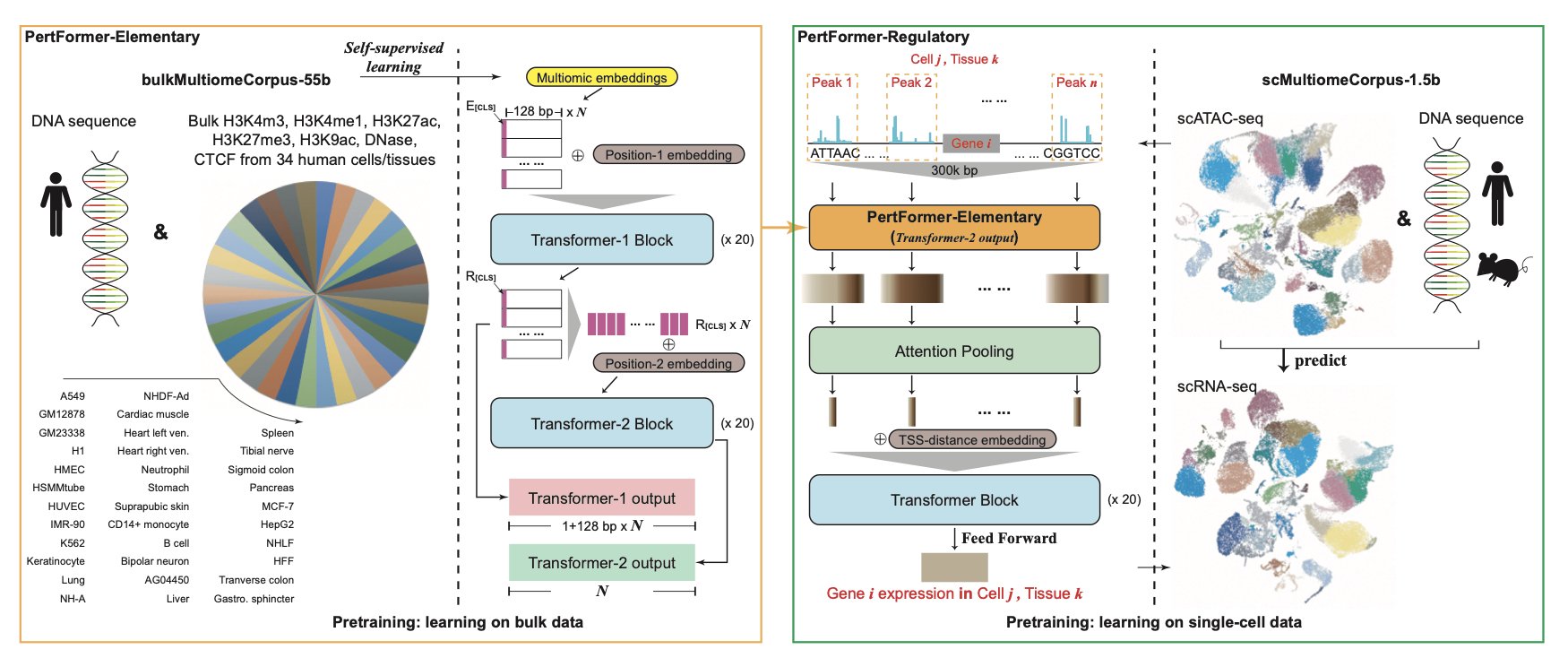

To understand a city’s traffic system, you can’t just look at a map (the genome). You also need to see real-time traffic (the transcriptome), subway lines (epigenetics), and more. PertFormer does just that. It integrates nine different types of biological data, or “multiomics,” to build a detailed digital model of how a cell works.

The model has two key modules: 1. PertFormer-Elementary: This part analyzes the “neighborhood” around a gene. It focuses on nearby regulatory elements like promoters and enhancers to understand how they directly affect gene expression. 2. PertFormer-Regulatory: This part observes the “city-level traffic planning.” It can see long-range regulatory interactions up to 300,000 base pairs away. Often, a gene’s on/off switch isn’t right next to it but far away. This module is designed to capture these distant interactions.

With these two parts, PertFormer can draw a complex map of gene regulatory networks (GRNs).

The Real Highlight: “Zero-Shot” Prediction

Most AI models need to see the “answer key” before they can solve a problem. For example, you would need to train it on experimental data from knocking out gene A before it could learn to predict the consequences of knocking out gene A.

PertFormer has “zero-shot” prediction capability. This means that even if the model has never seen a perturbation of a specific gene during training, it can accurately predict what will happen when that new gene is perturbed, based on the general biological rules it has learned.

It’s like an experienced doctor who has never seen your rare disease but can infer its cause and potential treatments based on a deep understanding of human physiology and pathology. This ability makes PertFormer broadly applicable, because it’s impossible to experimentally test every possible perturbation combination for all 20,000-plus genes.

Does It Actually Work?

A model is only as good as its results. The researchers used PertFormer to do several convincing things:

First, they had the model predict the transformation of normal somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). This is a complex cellular reprogramming process involving the coordinated changes of many genes, and PertFormer accurately simulated this transition.

More importantly, they applied the model to cancer. The researchers used PertFormer to find new therapeutic targets in triple-negative breast cancer and ovarian cancer cells. The model produced a ranked list of predictions. They then went back to the lab and experimentally validated several of the top-ranked targets. The results showed that these new targets, predicted by AI, did effectively inhibit tumor cell growth.

This elevates PertFormer from an academic tool to something with the potential to change the drug discovery pipeline. In the future, we could first screen and rank thousands of potential targets on a computer, then take only the most promising candidates into the lab for validation. This could save a great deal of time and R&D costs.

For researchers, tools like PertFormer don’t just help us find targets faster. Through their attention mechanisms, they can also tell us “why” a target is important, offering a new perspective for understanding disease mechanisms. The model still has room for improvement, but the direction it points to is clear: in the future of drug discovery, computation and experimentation will become ever more closely intertwined.

📜Title: Multimodal foundation model predicts zero-shot functional perturbations and cell fate dynamics 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.12.19.629561v2 💻Website: https://pertformer.ibreed.cn