Table of Contents

- Natural proteins have evolved a very high robustness to mutation, likely as a defense against the cell’s natural “error rate” during transcription and translation.

- AlphaFold 3 makes it possible to accurately predict glycan structures for the first time, but interpreting and validating the results is crucial due to the inherent flexibility of glycans.

- PPB3 uses deep learning and the massive ChEMBL database to offer a free, accurate drug target prediction tool that can identify the polypharmacological effects of drug molecules.

1. The Evolutionary Puzzle of Proteins: Why Are They So Tolerant to Mutations?

We deal with protein mutations all the time. Whether we’re trying to boost an enzyme’s activity or study drug resistance in a target, the first thing we often do is site-directed mutagenesis. Sometimes, changing just one amino acid can completely deactivate a protein. Other times, you can swap several and nothing much happens. What’s the pattern here? A recent study offers an explanation from an evolutionary perspective.

Researchers wanted to answer a question: just how “tough” are natural protein structures when faced with mutations? In other words, how robust are they?

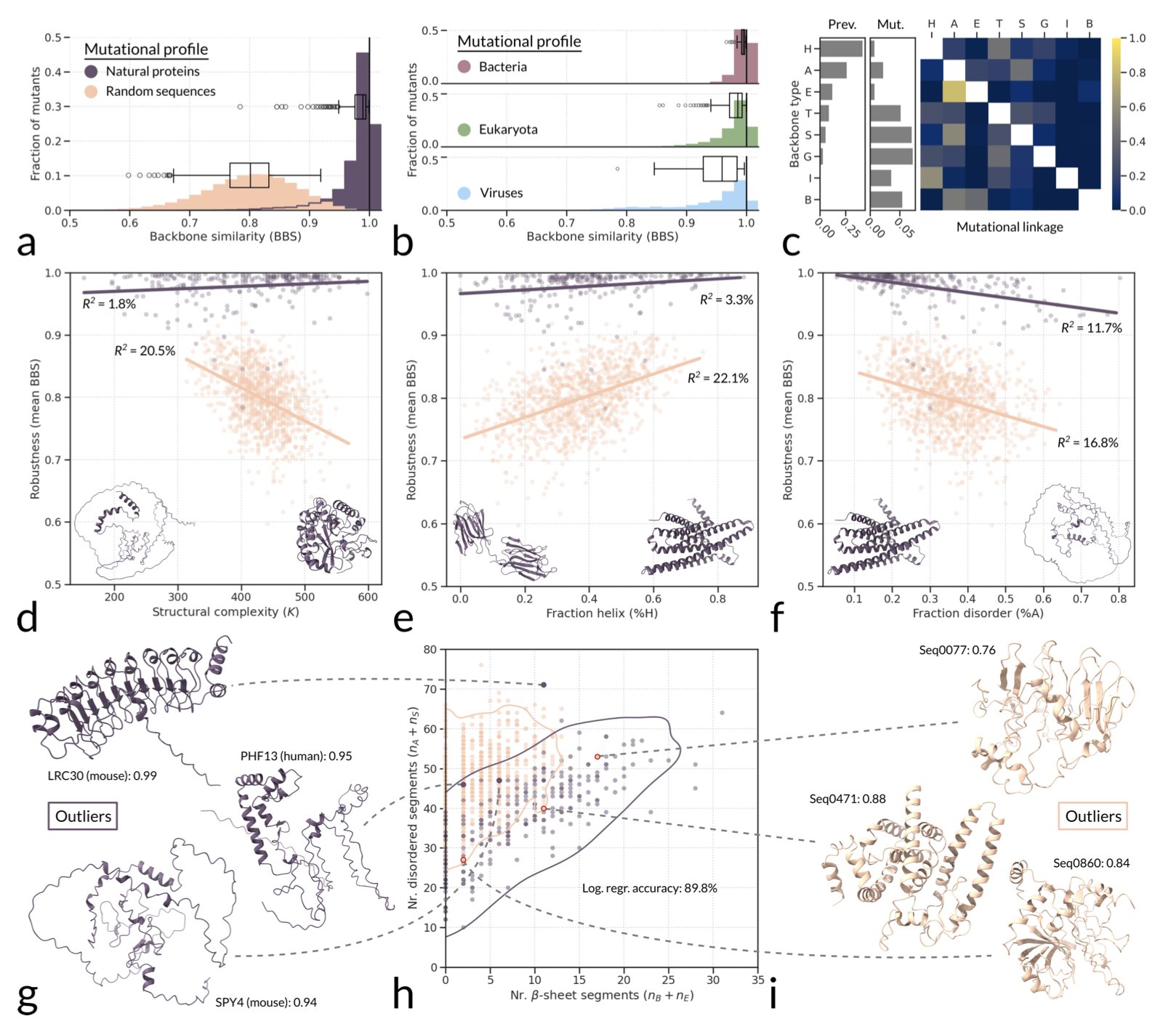

Here’s what they did. They created three sets of protein sequences: the first set came from nature; the second was made of completely random amino acid sequences; and the third was designed from scratch computationally (de novo).

Then, they used a structure prediction tool called ESMFold. For each sequence, they introduced a large number of single-point mutations and used ESMFold to predict the new structure. They then checked how much the mutated structure had changed from the original.

The results showed that natural proteins were surprisingly robust. Most single-point mutations had little effect on their overall 3D structure. It was like throwing a pebble at a building—the building just shakes a little.

In contrast, the random sequences and many of the de novo proteins were much more fragile. They were like towers built from blocks, where a slight nudge could make them fall apart. A single amino acid change could cause the entire structure to collapse or refold into something completely different.

This finding suggests that the toughness of natural proteins isn’t an accident; there must be a specific reason for it.

The researchers first ruled out one possibility: what about RNA? They compared proteins to RNA and found a completely different story. The mutational robustness of natural, functional RNA was about the same as that of random RNA sequences. This means the high robustness of proteins is unique and must be the result of strong evolutionary selection pressure.

So, where does this pressure come from? Could the genetic code itself be “cheating”? For example, maybe codons are designed so that mutations tend to produce amino acids with similar chemical properties. The researchers checked this too. The genetic code does help a little, but the effect is too small to explain the huge robustness gap between natural and random proteins.

Finally, the authors proposed a convincing hypothesis: this selection pressure likely comes from the “production errors” that are constantly happening inside the cell.

We know that transcription and translation in a cell are not 100% accurate; there’s always an error rate. If a protein’s structure is designed to be precise but fragile, a tiny translation error could produce a misfolded, non-functional, or even toxic protein. This would be a huge waste and risk for the cell.

So, what was evolution’s solution? It selected for proteins with a high tolerance for these production errors. A protein whose overall structure and function remain stable, even if an amino acid is replaced by mistake during translation, would clearly be favored by evolution.

This research has implications for drug development.

First, it explains why designing a stable, functional protein from scratch is so difficult. The proteins we design, like the “de novo” proteins in the study, haven’t gone through billions of years of evolutionary filtering for “fault tolerance,” so they are naturally more fragile.

Second, for drug targets, this robustness could be a new dimension for evaluation. Does a highly robust target have more ways to evolve drug-resistance mutations without sacrificing its essential function?

This work makes us see proteins in a new light. They are not just precise molecular machines built for a specific function, but also highly fault-tolerant masterpieces, evolved to work reliably in a noisy and error-prone cellular environment.

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.27.672565v1

2. AlphaFold 3 Takes on Glycan Modeling: Big Potential, but Caution is Needed

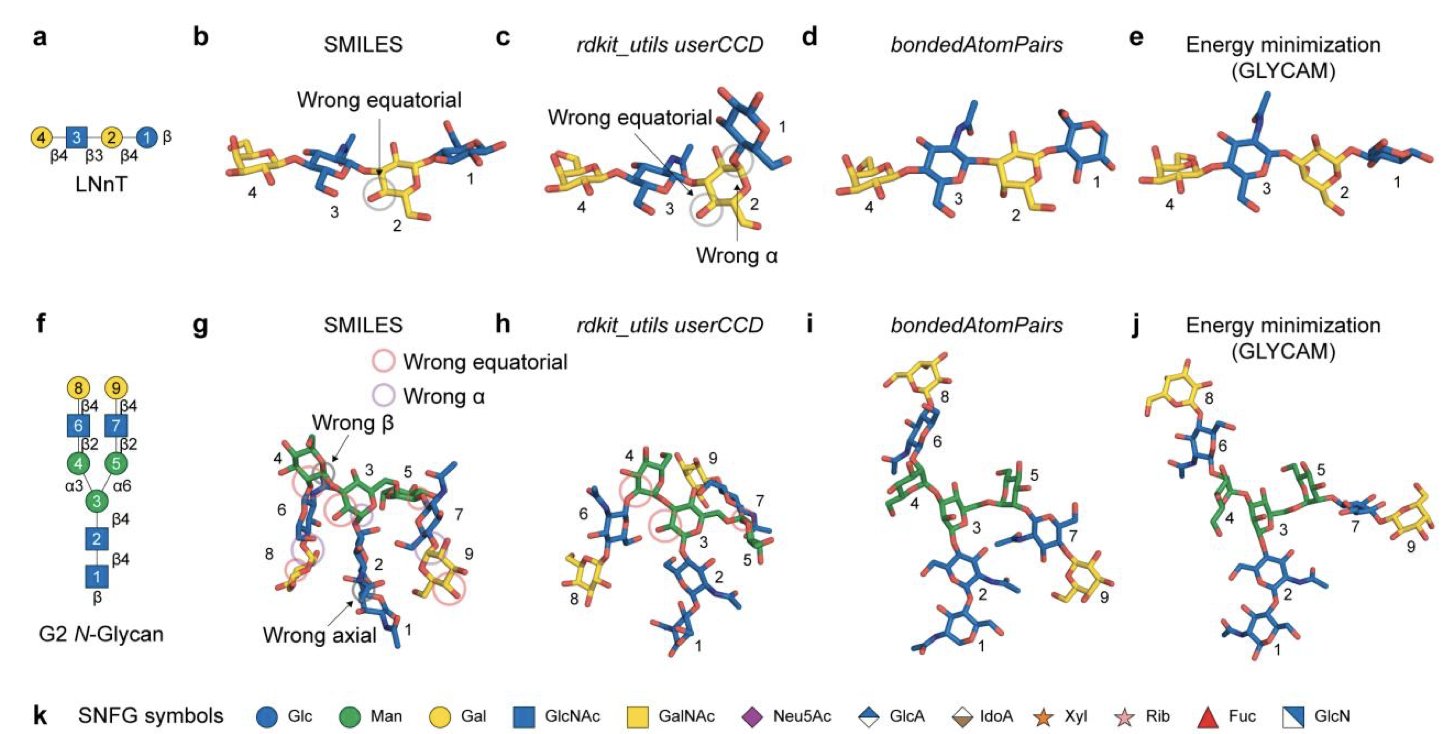

In structural biology, predicting the conformation of glycans has always been a tough problem. A protein is like a string of 20 different kinds of beads (amino acids) with relatively clear folding rules. A glycan, however, is more like a string of many different kinds of beads (monosaccharides) linked in various ways (glycosidic bonds). The connection points aren’t fixed, and they can form all sorts of branches. This makes glycan structures extremely flexible, like a wet noodle, making it hard to find a single stable, “correct” conformation.

AlphaFold 2 was successful at predicting protein structures, but it could do almost nothing for glycans. AlphaFold 3 (AF3) was designed from the start to handle a wider range of molecules, and glycans were one of the most anticipated types.

This new study is a stress test of AF3 in the field of glycan modeling. The researchers first had to solve a basic problem: how do you tell AF3 you want to model a glycan?

They found the most effective way was to use a hybrid grammar. It’s like giving AF3 a set of Lego bricks. First, the researchers used the Chemical Component Dictionary (CCD) to define the basic “building blocks,” like the various monosaccharide rings. Then, they used bondedAtomPairs (BAP) to tell AF3 exactly how these blocks connect. This prevents AF3 from having to build a chemically correct sugar ring from the atomic level up, which reduces the chance of errors.

With this method, the researchers applied it to real biological problems, like simulating complexes of enzymes and glycoproteins. The results were encouraging. AF3 could not only accurately predict the overall structure of the complexes but could even capture some intermediate states consistent with physiological processes. This suggests that AF3’s predictions may reflect parts of a biological process. The study showed that AF3 could predict glycoprotein complex structures that it had never seen in its training data. This is a strong sign that AF3 has the ability to generalize, not just memorize and reproduce data from its training set.

Of course, we shouldn’t get too optimistic yet. AF3 provides a static snapshot of the lowest-energy conformation. But glycans are highly dynamic under physiological conditions, and their biological function is often determined by an ensemble of conformations, not a single one. So, AF3’s output shouldn’t be treated as the final answer. It’s more of a high-quality starting point. After getting a model, we still need to use methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to explore its dynamic behavior and validate it with experimental data.

This work provides a useful toolbox for researchers, including input templates and examples, lowering the barrier to using AF3 for glycan research. It’s not a solution to every problem, but it is a powerful new tool that, for the first time, gives us the ability to systematically explore the complex world of glycobiology.

📜Title: Modeling glycans with AlphaFold 3: capabilities, caveats, and limitations 📜Paper: https://academic.oup.com/glycob/advance-article/doi/10.1093/glycob/cwaf048/8242499

3. A New AI Target Prediction Tool, PPB3, Is Now Available for Free

In drug discovery, we want to design molecules that act like precision-guided missiles, hitting only their intended targets. But the reality is that almost all small-molecule drugs are more like “shotguns,” hitting multiple targets at once. This phenomenon is called polypharmacology. It can lead to side effects, but it can also be a source of new therapeutic effects. That’s why figuring out a molecule’s potential target profile early on is critical.

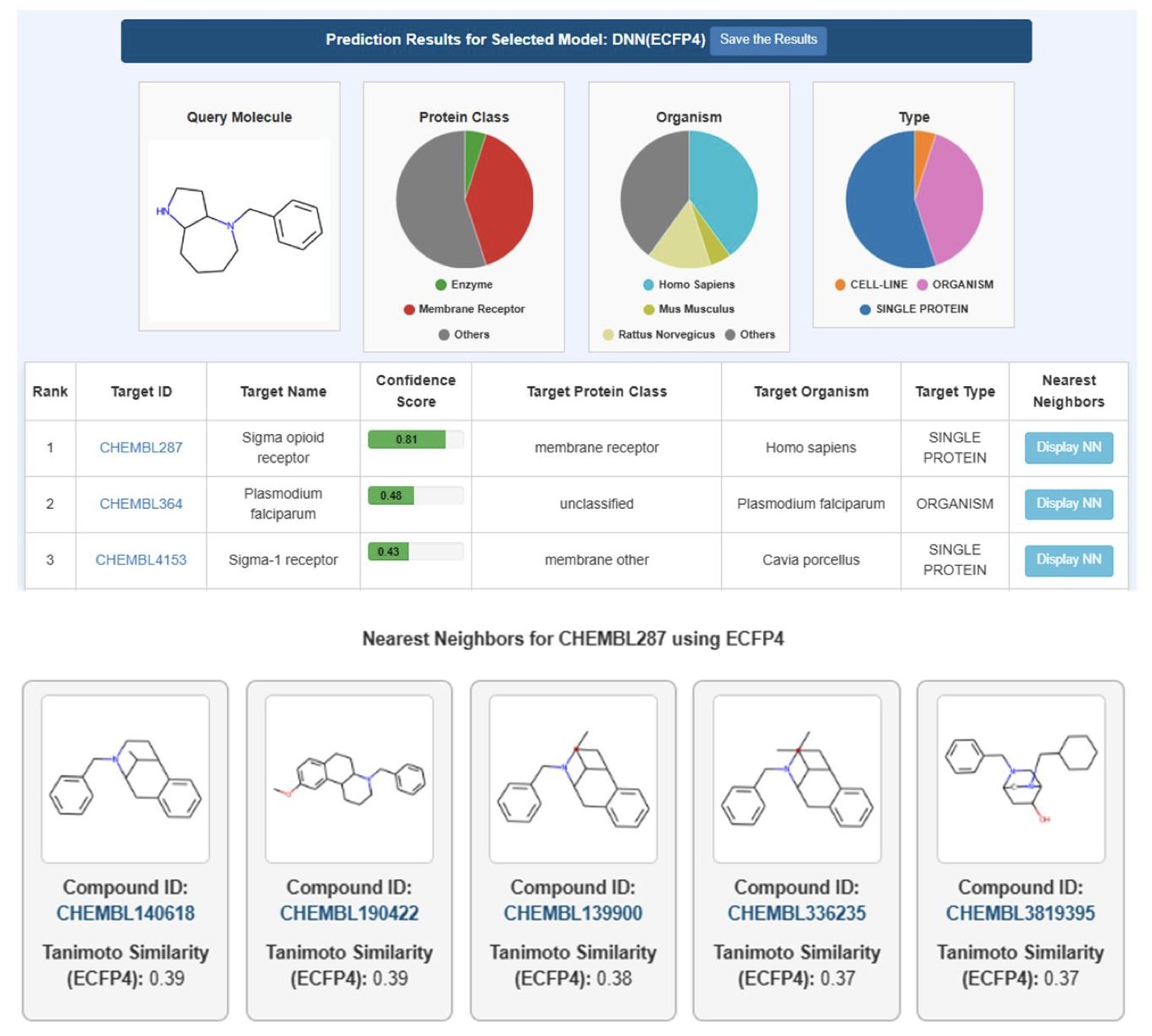

A new online tool, Polypharmacology Browser PPB3, is now available to help solve this problem.

Its first highlight is the data. Many older prediction tools were trained on limited data. PPB3 uses the ChEMBL 34 database, which contains over 1.1 million compounds and more than 7,500 targets.

These targets aren’t just single, purified proteins. PPB3’s training set also includes data from cell lines and even whole organisms. This makes the model’s predictions more relevant to real biological settings, not just idealized lab experiments.

Good ingredients need a good chef. At the core of PPB3 is a deep neural network. Here’s how it works: you input the structure of a molecule, and the system converts it into a digital code called a “molecular fingerprint.” Then, the deep learning model analyzes this fingerprint and, based on the “experience” it gained from the massive dataset, predicts a list of the most likely targets for that molecule.

How well does it actually work? The researchers did a case study with a new molecule. They compared PPB3’s predictions with its previous version and several other public online tools. The results showed that PPB3 found more known, true targets while reporting fewer false positives.

This is very valuable in practice. A prediction tool that reports a lot of unreliable targets can cause experimental scientists to waste a lot of time and resources on validation. A “cleaner” prediction means higher efficiency.

As a free web tool, PPB3 gives drug discovery researchers a convenient starting point. When you design and synthesize a new compound, before you commit to expensive cell or animal experiments, you can run it through PPB3. In a few minutes, you’ll get a report on its potential target profile. This report can help you foresee potential off-target toxicities (for example, will it hit the hERG channel and cause cardiotoxicity?) or inspire new therapeutic directions.

📜Title: Polypharmacology Browser PPB3: A Web-based Deep Learning Tool for Target Prediction Using ChEMBL Data 📜Paper: https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/68aefa76728bf9025e9acf63