Table of Contents

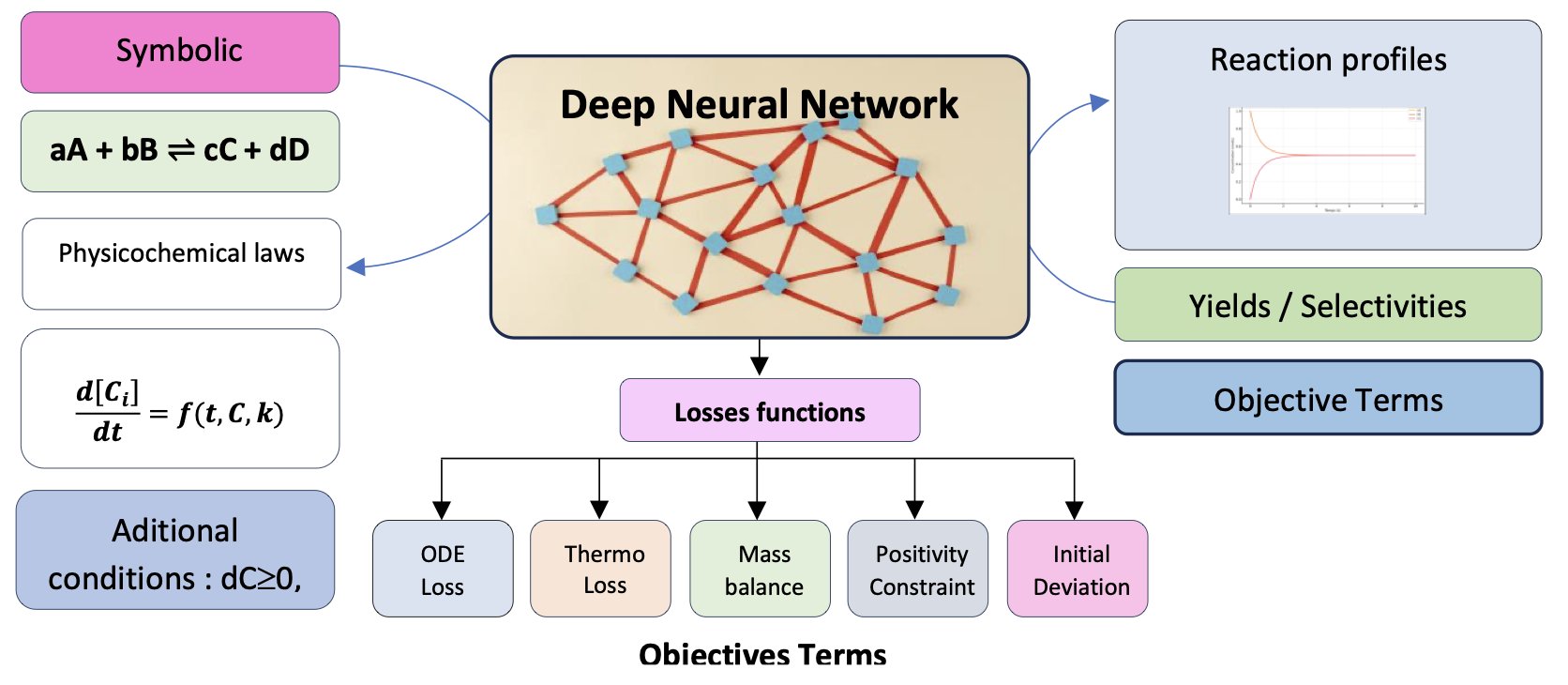

- ChemAI writes physicochemical laws into its code, enabling it to simulate reactions using only chemical equations, ending the reliance on vast experimental datasets.

- This study shows that a simple AI model, forced to learn real molecular interactions through a “molecular dropout” training method, can outperform more complex models in predicting binding affinity.

- The CSGD model applies score-matching techniques to discrete molecular graphs, allowing us to precisely generate desired molecules by freely combining multiple conditions, much like adjusting a recipe.

1. ChemAI: Teaching AI Chemistry with the Laws of Physics

We’ve always wanted a model that could tell us how a new reaction will proceed without having to run it in a flask. Traditionally, this required large amounts of experimental data to fit kinetic models, which is both time-consuming and labor-intensive. But most machine learning models are data-hungry, like students who only memorize answers and are stumped by new types of questions.

A new paper introduces a model called ChemAI that tries to solve this.

Its starting point is the chemical reaction equation itself. You give it a reaction like A + B → C, and it can tell you how the concentrations of A, B, and C will change over time. It doesn’t need you to provide a bunch of experimental data points to learn from.

How does it do this?

The key is its custom loss function.

Think of it this way: most machine learning models aim to minimize the difference between their predictions and the actual data points. ChemAI goes a step further. It must not only fit the data but also obey fundamental laws of physical chemistry. The researchers wrote these laws—like mass conservation, chemical kinetics, and thermodynamic equilibrium—directly into the model’s “grading criteria.”

For example, during training, if a prediction shows that the total mass of the reactants increased, the model receives a huge penalty for violating the law of mass conservation. Similarly, predicted concentrations cannot be negative, and reactions must eventually approach equilibrium. These are hard constraints.

This way, ChemAI isn’t just memorizing data; it’s learning the underlying rules that govern chemical reactions. It translates a symbolic chemical equation into a physically self-consistent system of differential equations and then solves it.

The benefits of this approach are clear. The paper shows ChemAI’s performance compared to other models, including Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and Transformers. When dealing with noisy data or predicting conditions outside its training range, ChemAI performs much better. This isn’t surprising. When data becomes unreliable, models that rely solely on data lose their way. But ChemAI always has the laws of physics as its compass.

The researchers used it to simulate complex reactions like Suzuki couplings. Anyone in organic synthesis knows that modeling these multi-step catalytic cycles is difficult due to their complex mechanisms and numerous intermediates. ChemAI’s ability to handle such nonlinear systems shows its potential as a practical tool.

We are one step closer to that ideal “virtual lab.” In the future, we might first use a tool like ChemAI to screen hundreds of reaction conditions on a computer, find the optimal few, and then validate them in the lab. This would be enormously valuable for process optimization and designing new reaction pathways in drug discovery.

📜Title: ChemAI: A Symbolically Informed Neural Network For Physicochemical Modeling Of Reaction Systems 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-2hp4c

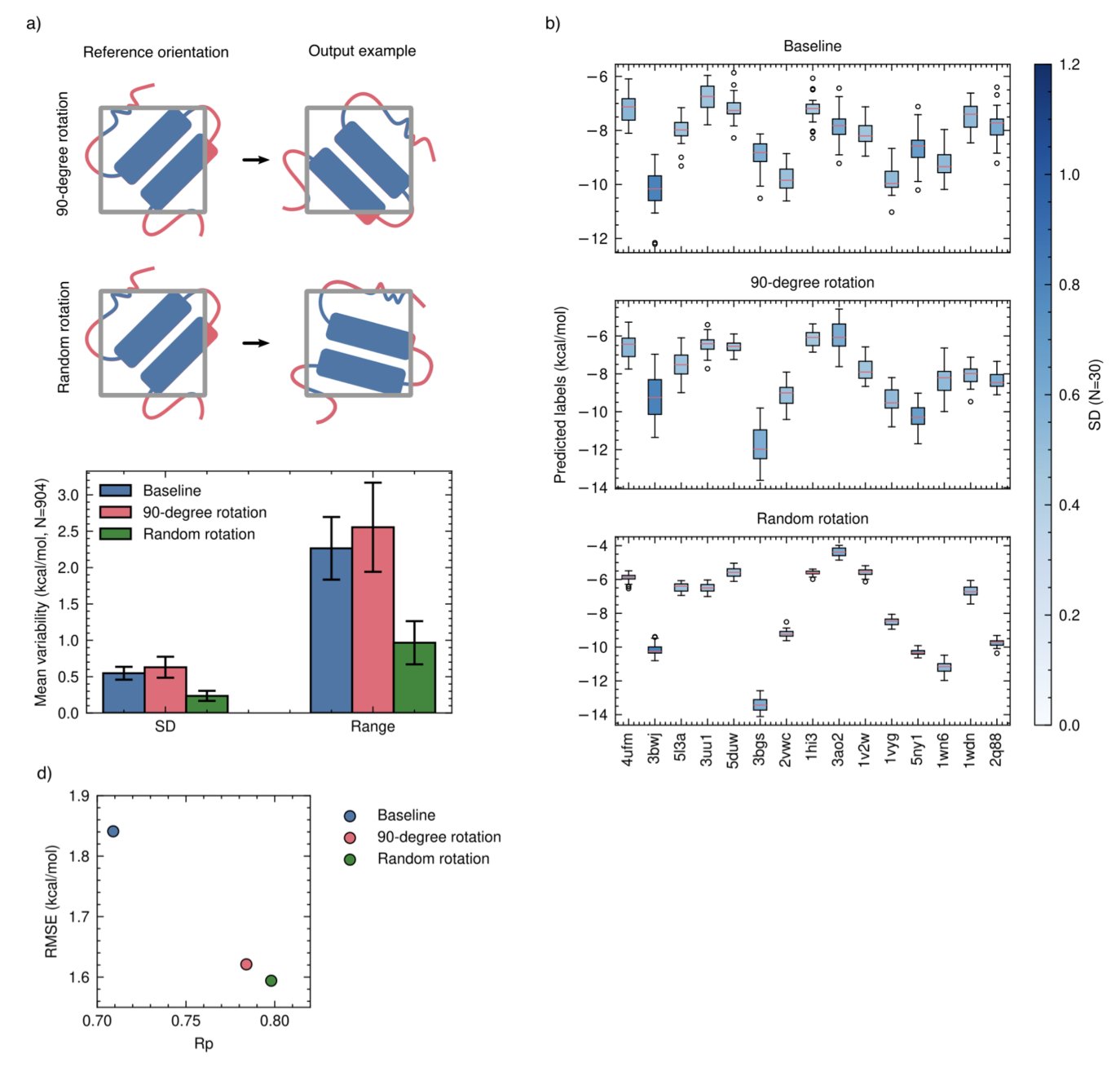

2. AI Predicts Binding Affinity: Training Matters More Than the Model

In computational drug chemistry, much research has focused on building larger, more complex neural networks to predict protein-ligand binding affinity. A new paper suggests a simpler solution, arguing that the key may not be the model architecture, but the training method.

How AI “Cheats”

The study found that many AI models don’t actually learn to understand the 3D interaction between a ligand and a protein’s binding pocket.

They learn to take a shortcut: memorization.

The model sees a ligand and identifies some of its chemical features. Then it sees a protein and identifies some of its hydrophobic features. The model then forms a simple association: this kind of molecule with this kind of protein usually gets a high score. It doesn’t care if the two actually fit together. This prediction method naturally fails when faced with new molecules or targets it has never seen before.

A Trick to Stop the Cheating: Molecular Dropout

To solve this, the researchers proposed a simple technique called molecular dropout.

Here’s how it works: during training, the model is randomly shown only the protein without the ligand, and it’s told the correct answer is “0,” meaning no binding. Or, conversely, it’s shown only the ligand without the protein, and the correct answer is again “0.”

This change fundamentally alters how the model learns.

It forces the AI to understand that it can’t guess the answer based on information from just one side. The model must look at both the protein and the ligand and understand their interaction to make a correct judgment.

Data Is King

The study also found that the method of data augmentation affects training. In the past, researchers would rotate molecules by fixed 90-degree angles. But this paper shows that rotating molecules completely randomly works better. This approach is closer to physical reality and teaches the AI to better understand rotational invariance.

The researchers applied these data-centric training methods to a simple Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) called DockTDeep, with impressive results.

This simple model performed on par with, or even better than, much larger and more complex models on a series of benchmarks. Its performance remained robust, especially on “out-of-distribution” test sets—entirely new molecules and targets the model had never seen.

On the path of AI-assisted drug discovery, instead of chasing bigger and deeper models, we might get better results by going back to optimize our data and training methods.

📜Title: Data-Centric Training Enables Meaningful Interaction Learning In Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.2643A/chemrxiv-2025-khbrl 💻Code: https://github.com/gmmsb-lncc/docktdeep

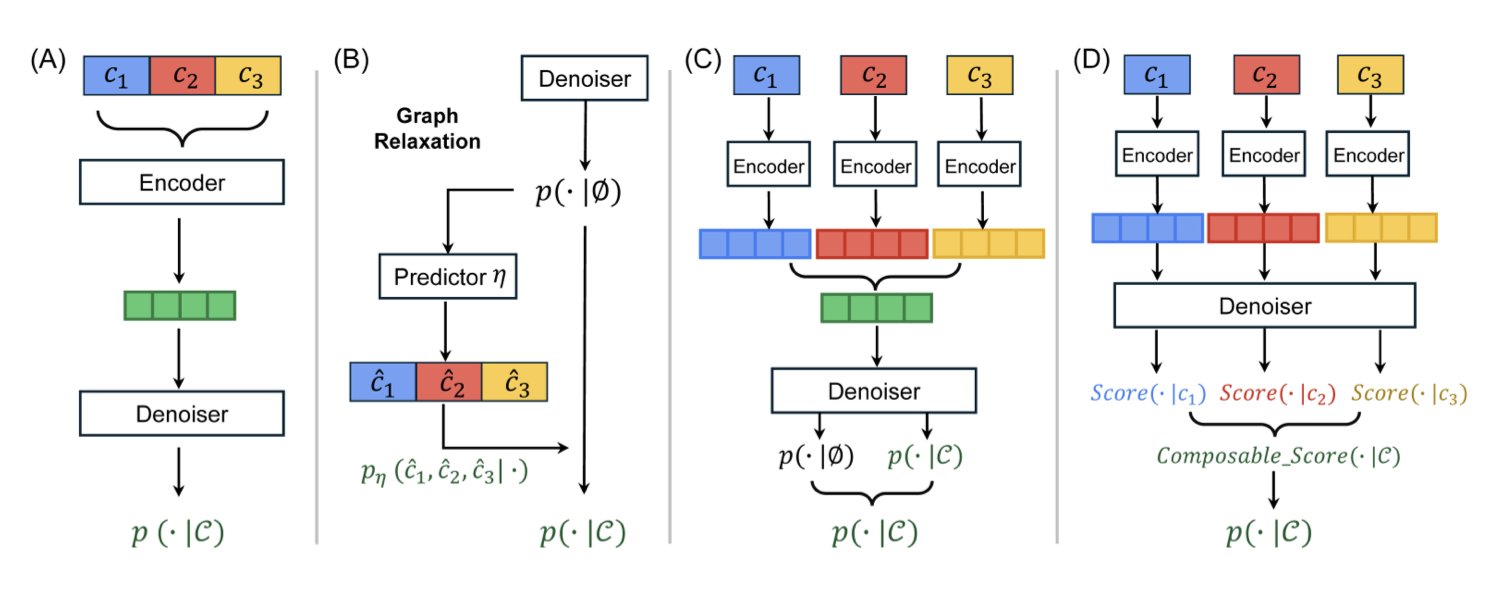

3. The CSGD Diffusion Model: Generating Molecules Precisely, Like Building with Lego

How do you design a molecule that simultaneously satisfies multiple, sometimes conflicting, properties?

For instance, we might want a molecule with high target activity, good water solubility, and low toxicity. This is like adjusting a complex audio mixer; pushing up one fader (like activity) might affect another (like solubility).

Previous generative models have been somewhat clumsy at this. They either required training a separate model for each combination of properties or used approximation methods that “blur” discrete molecular structures into continuous data. The latter approach works but often sacrifices the precision of the chemical structure, leading to chemically impossible (“invalid”) molecules.

CSGD’s Solution: A “Navigation System” for Discrete Molecular Graphs

The CSGD (Composable Score-based Graph Diffusion) model in this paper offers a more elegant solution. Its core idea is to successfully adapt score matching, a technique that has been very successful in image generation, to the generation of discrete molecular graphs.

You can think of score matching as a navigation system. In image generation, the model starts with random noise, and the navigation system tells each pixel which direction to “move” in, step by step, eventually forming a clear picture. This process is natural in a continuous space. But molecules are discrete; there is either a bond between atoms or there isn’t. There’s no such thing as “half a chemical bond.”

CSGD’s cleverness lies in a mechanism called “concrete scores,” which equips this discrete generation process with its own navigation. The model no longer tells an atom to “move 0.5 units to the left.” Instead, it calculates the “optimal probability” of adding an atom or a chemical bond at the current step.

Two Key Tools: CoG and PC

To make this navigation system more powerful and reliable, the researchers developed two key components:

Composable Guidance (CoG): This is the “audio mixer.” It allows you to dynamically and freely combine different guiding conditions during generation. You can decide at any moment, “Right now, I’m focusing on solubility,” or “Next, let’s turn up the weights for both activity and low toxicity.” This flexibility is a huge advantage because you don’t need to retrain the model to explore endless combinations of properties. Experiments show that CoG’s performance is comparable to the popular Classifier-Free Guidance (CFG), but it is far more flexible.

Probability Calibration (PC): This is the “quality inspector.” There’s always some discrepancy between the data a model sees during training and the situations it encounters during actual generation. PC’s job is to correct this discrepancy. It fine-tunes the probabilities for generating the next structure, ensuring the final output is more chemically sound and thus increasing the molecule’s validity.

How Does It Perform?

Tests on four public datasets showed that CSGD improved the “controllability” metric by an average of 15.3% over the previous best methods. When researchers set desired properties, CSGD was more accurate in generating molecules that met those requirements. At the same time, it produced a high rate of valid molecules, avoiding wasted computational resources.

Tools like CSGD are changing the old “finding a needle in a haystack” approach to screening molecules, allowing us to design them more proactively and precisely. This could not only accelerate the optimization process from hit to lead compounds but also opens a new door to exploring a broader and more diverse chemical space.

📜Title: Composable Score-based Graph Diffusion Model for Multi-Conditional Molecular Generation 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.09451