Table of Contents

- The CBYG framework offers a more stable and controllable method for 3D molecule generation than diffusion models, using Bayesian Flow Networks and gradient guidance for structure-based drug design.

- In molecular language models, bigger isn’t always better. MolEncoder shows that an optimized pre-training strategy is key, not just larger models and datasets.

- DeepSEA is an explainable deep learning model that can bypass the limitations of sequence alignment to more accurately identify new antibiotic resistance proteins and explain how they work.

1. CBYG: A New Approach to 3D Molecule Generation Beyond Diffusion Models

In my years working in AI for drug discovery (AIDD), I’ve seen an explosion of generative AI models. For structure-based drug design, diffusion models have become almost standard. But if you’ve ever run these models yourself, you know how unpredictable they can be. You might ask for a molecule with high affinity, and it gives you a structure that’s chemically impossible. The core problem is that these models struggle to handle two things at once: the 3D spatial positions of atoms (continuous coordinates) and the types of atoms (discrete chemical elements). They’re like two dance partners who are completely out of sync.

This new work from Choi and colleagues introduces the CBYG framework to solve this problem. They use Bayesian Flow Networks (BFNs).

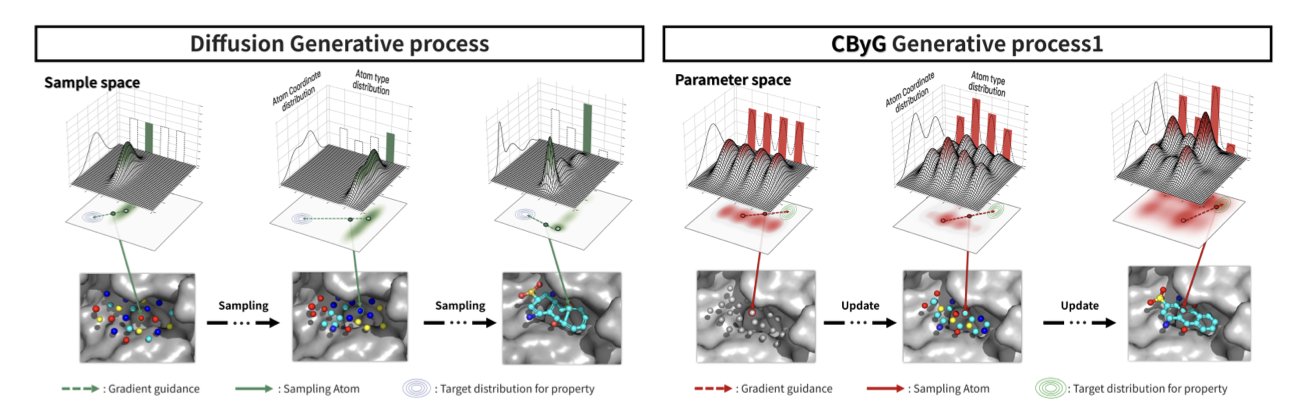

Here’s one way to think about the difference. Diffusion models work by starting with a random cloud of “atoms” (noise) and then “denoising” it step by step to sculpt a molecule. The process is powerful, but each correction can introduce uncertainty. When you try to apply external guidance, like “increase affinity,” the whole system can easily fall apart.

BFNs work more like building with blocks. They follow a clearer, more orderly path, starting from a simple initial state and gradually building the final, complex molecule through a series of learnable “flow” transformations. This process is inherently more stable.

The essence of CBYG is that it adds a precise “navigation system”—gradient guidance—to this stable BFN foundation. At each step of molecule generation, this system calculates a “gradient” based on our goals (like binding affinity, synthetic feasibility, or selectivity). Then, it applies a small push to nudge the generation process in the right direction.

Think of it this way: instead of carving a molecule from a block of marble with big, bold strokes, we’re using a 3D printer to build it layer by layer. We can make tiny adjustments at each layer to ensure the final product matches the design perfectly. This approach makes the entire generation process controllable. When you want to make a molecule a little “better,” the model doesn’t give you something completely wild. It makes steady improvements on what it already has.

What I also appreciate is the evaluation system the researchers designed. Many AI papers focus on scoring high on academic benchmarks that are far removed from the daily needs of the pharmaceutical industry. This time, they focused on “hard metrics” we actually care about: binding affinity, synthetic accessibility score (SA score), and selectivity. The results show that CBYG outperforms current mainstream models on these practical benchmarks.

For us, it’s no longer a “black box” full of surprises (and scares), but a reliable engineering system that seems to understand our chemical intuition. CBYG isn’t the final answer, of course, but it points in an attractive direction: making AI molecule generation more like a rigorous engineering discipline and less like a dark art.

📜Title: Controllable 3D Molecular Generation for Structure-Based Drug Design Through Bayesian Flow Networks and Gradient Integration

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.21468v1

2. MolEncoder: Moving Past “Bigger is Better” for Molecule Pre-training

In recent years, one idea has dominated AI: the bigger the model and the more data, the better the results. From GPT to image generation models, this “brute force” approach seems to work every time. The drug discovery field has tried to follow suit, developing “molecular language models” based on molecule SMILES sequences. But molecules are not language, and simply copying best practices from Natural Language Processing (NLP) hasn’t worked well.

This new study shows that this direct transfer doesn’t work.

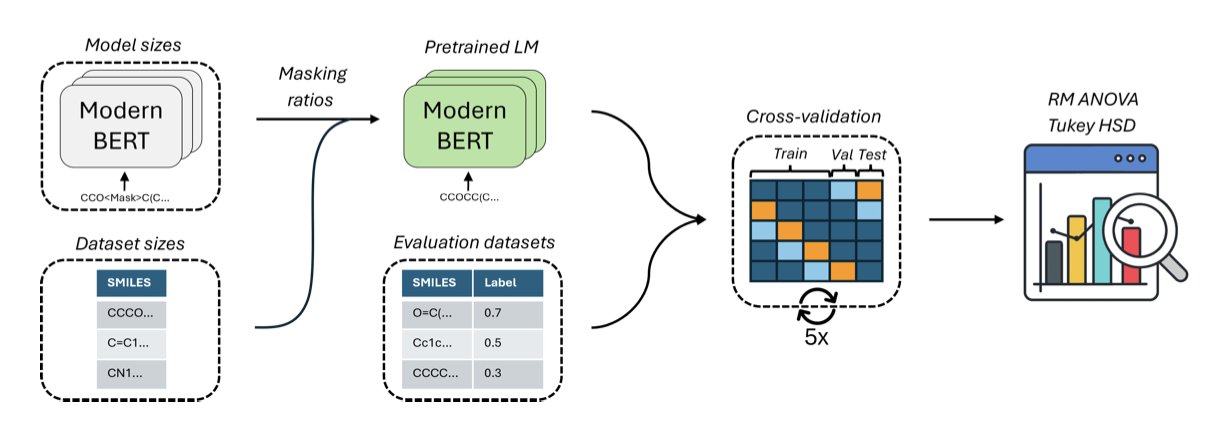

These models work by treating a molecule’s SMILES string, like CCO (ethanol), as a sentence. The core of pre-training is “Masked Language Modeling,” which is basically a fill-in-the-blanks game. You randomly mask parts of the sentence and ask the model to guess what’s missing. For example, CCO becomes C[MASK]O, and the model has to guess that the masked token is C.

In NLP, the golden rule is to mask 15% of the words. But the researchers found this rule doesn’t work well for molecules. The grammar of molecules is much stricter than human language. In English, you can swap “a quick brown fox” with “a fast brown fox,” and the meaning is similar. In chemistry, if you change one carbon in ethanol (CCO) to a nitrogen (CNO), you get a completely different substance.

So, the researchers tried increasing the masking rate. They found that when the rate was increased to 30%, the model’s performance on downstream tasks (like predicting molecular properties) improved significantly. This is like giving the model a harder test, forcing it to stop memorizing local SMILES patterns and start understanding the deep chemical rules that make a molecule stable and effective.

Another finding relates to model and data size. We usually assume that the more parameters a model has and the more molecules it’s seen, the more “knowledgeable” it will be. But the results show that a medium-sized model with only 15 million parameters performed best when pre-trained on half of the ChEMBL dataset. Increasing the model size or feeding it the entire dataset actually made performance worse.

This suggests there’s a “sweet spot” for tasks like predicting molecular properties. Beyond this point, a larger model might start learning noise, or in other words, more parameters and data bring diminishing returns. This is good news for labs with limited computing resources. We don’t need to chase giant models with billions of parameters to get top-tier results.

Based on these findings, the authors built MolEncoder. It’s a BERT model carefully tuned within this “sweet spot.” On several industry-standard test sets, the compact MolEncoder matched or exceeded the performance of larger, more complex models like ChemBERTa-2 and MoLFormer. It does a better job with fewer computational resources.

Finally, the study also points out that pre-training loss is not a good predictor of a model’s performance on real-world tasks. Many teams fixate on this number, thinking that the lower it is, the better the model. But the truth is, you have to test the model on actual downstream tasks to know how well it really performs.

📜Title: MolEncoder: Towards Optimal Masked Language Modeling for Molecules

📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-h4w9d