Table of Contents

- Massive sampling can improve AlphaFold’s predictions for complex protein interfaces, but picking the best model from a huge pool remains a key challenge.

- LightChem combines the reasoning power of large language models with established computational chemistry tools, offering chemists a lightweight, accurate, and professional AI assistant.

- Researchers have developed a new guided docking method that uses the structure of water molecules in a protein’s binding site as a roadmap, solving the challenge of docking flexible glycans.

1. AlphaFold by Brute Force? How Massive Sampling Tackles Protein Complexes

AlphaFold2 is a groundbreaking tool. Its ability to predict single protein structures is impressive. But when used for Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs), especially for predicting how two proteins bind, it can sometimes get it wrong. Think of it like a top student who aces basic questions but might not give a clear answer on a complex, multi-part problem.

A standard AlphaFold run usually gives you five models. If none of them look right, or if they vary wildly from one another, you’re usually stuck. This happens a lot with “difficult” targets that have complex and flexible binding interfaces.

Sometimes, brute force just works

The researchers behind this paper tried a simple, direct approach: if five models aren’t enough, generate 8,000. This is called “Massive Sampling.”

The logic is straightforward. AlphaFold has a random element when it explores possible shapes. Running it more times gives it more chances to stumble upon the correct conformation. It’s like looking for a specific grain of sand on a beach. Grabbing five handfuls might not work. But if you bring in a truck and sift through the entire area, your chances of finding it go way up.

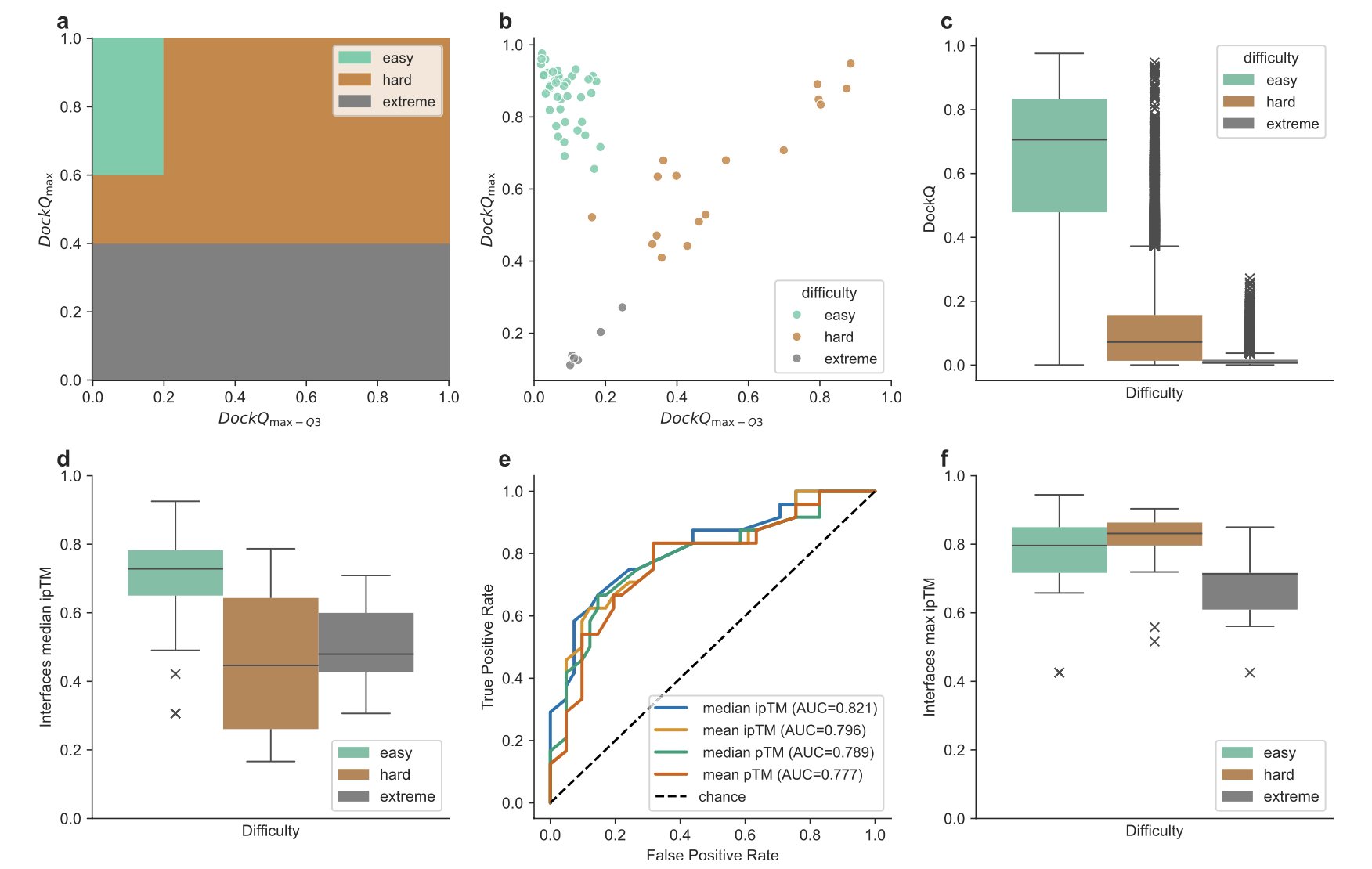

The researchers tested this method systematically at the CASP16-CAPRI competition. They sorted protein complex interfaces into three categories based on prediction difficulty: “easy,” “hard,” and “extreme.” The results showed that for “hard” interfaces, massive sampling almost always generated high-quality structural models, a clear improvement.

A “lazy” method

Generating 8,000 models for every protein would be computationally expensive, requiring supercomputer clusters.

So, the smartest part of this work is that they found a way to decide when to use massive sampling.

First, they run AlphaFold in standard mode to get a few models. Then they calculate the median interface predicted TM score (ipTM). You can think of the ipTM score as AlphaFold’s confidence in its own prediction of the interface region. If the median score is low, it means AlphaFold itself is uncertain about how to handle the interface.

That’s the signal. When they see it, they switch to massive sampling mode.

This approach is practical. It focuses computational resources where they’re needed most, avoiding waste on targets that were simple to begin with. According to their data, this strategic sampling reduced the total number of predictions from 8,040 models to 2,475, with almost no loss in prediction accuracy.

A new challenge: Finding a needle in a haystack

Massive sampling solves one problem but creates another.

Now you have 8,000 models, and hidden among them is likely the “gold standard” structure. But how do you find it?

AlphaFold’s built-in model ranking scores aren’t as reliable in this scenario. Picking the single best candidate from 8,000 highly similar options is a huge challenge for current scoring functions.

The researchers admit they haven’t solved this problem. But they did something even more valuable: they released all their data publicly, including every model, AlphaFold’s scores, and the official competition evaluation results.

This is a valuable resource for the entire field. It provides an excellent training and test set for anyone developing algorithms. Now they can try to build more accurate scoring functions to solve this “needle in a haystack” problem.

For researchers, this work offers a new way to handle difficult PPI targets. If you have a high-value complex that AlphaFold predicts poorly, you might consider investing the computing power for massive sampling. It could lead to a breakthrough. At the same time, it points to the next technical hurdle: developing scoring algorithms that can accurately pick the best model out of a massive dataset.

📜Title: MassiveFold Data for CASP16-CAPRI: A Systematic Massive Sampling Experiment 📜Paper: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/prot.70040

2. LightChem: A Lightweight AI That Understands Chemistry for Accurate Molecular Predictions

Large Language Models (LLMs) know a lot about a lot of things, but ask one to design a drug molecule or plan a synthesis route, and the results are often wrong. It’s like asking a generalist to perform highly specialized surgery—it’s risky. Chemistry is a precise discipline; small errors can have big consequences.

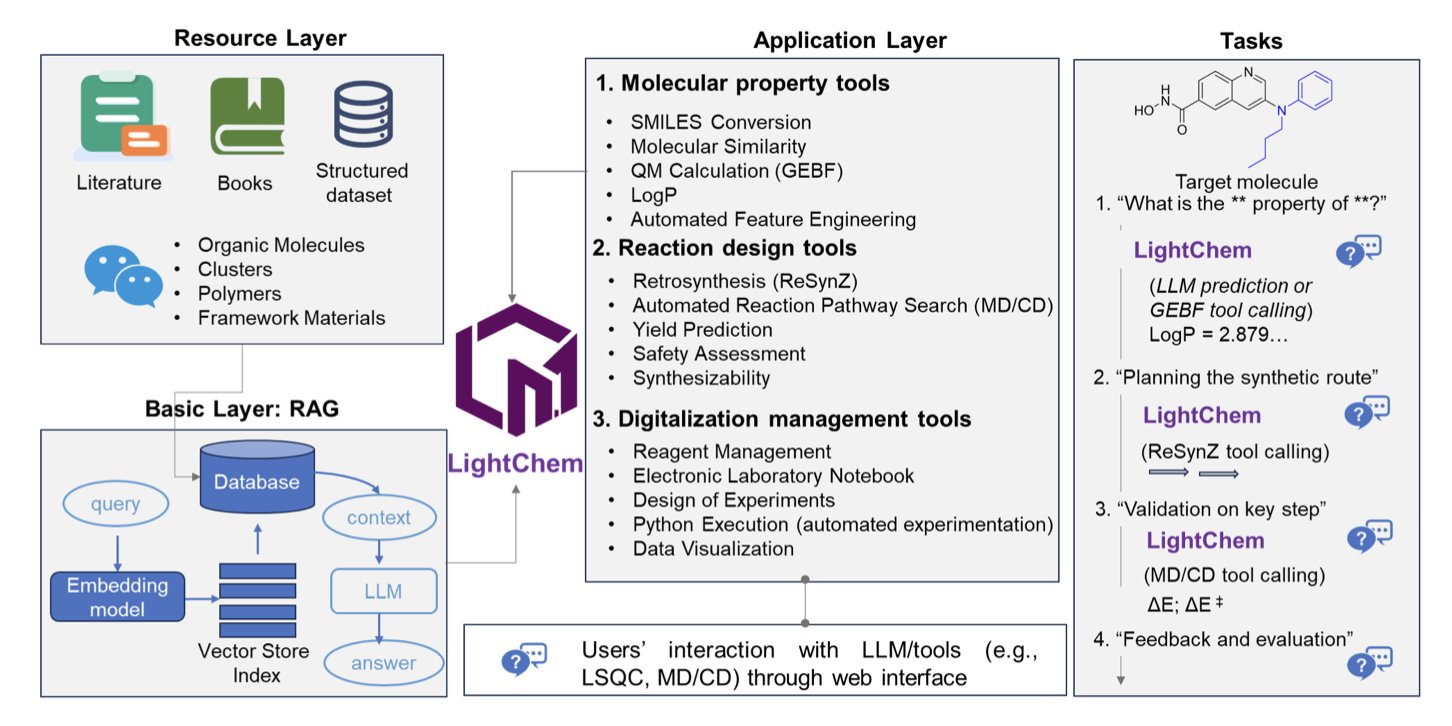

The creators of LightChem took a different path. They designed LightChem to be a professional “project manager.” It doesn’t know all the chemical details itself, but it knows where to look things up (retrieval-augmented generation) and which “expert” (specialized tool) to call for a specific problem.

This architecture is the core of their work. When a user asks a chemistry question, like predicting a molecule’s partition coefficient (PoLogP), LightChem doesn’t “create” an answer based on the text it has read. Instead, it activates a specialized module designed for that exact calculation, like a PoLogP prediction tool, and then presents the precise result in natural language.

This fundamentally solves the problem of general-purpose models making mistakes in specialized fields. For researchers, reliability is everything.

Its integrated “team of experts” includes the ReSynZ module for retrosynthesis planning and quantum chemistry packages like CIM and GEBF for high-precision calculations. LightChem’s capabilities are built on these computational methods, which are already widely validated by the chemistry community. It acts like an experienced scientist with a well-equipped computational chemistry team in the background.

The researchers demonstrated its abilities with several examples. Predicting the physicochemical properties of drug candidates and designing synthesis routes are routine tasks for medicinal chemists. LightChem can handle them. It can also manage larger-scale computations, like simulating the binding energy of molecules in zeolite clusters or the excitation energy of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) chromophore, with results that match experimental values.

Of course, it’s not a silver bullet. The authors are upfront that the model’s performance still needs improvement when predicting the HOMO-LUMO gap and optical properties of complex aggregates. This honesty defines the tool’s limits, letting us know when we can trust it and when we should be cautious.

Finally, the tool is available through a web interface, which packages complex algorithms and makes them easier to use. It’s not just a theoretical model; it’s a practical assistant that can be integrated into a lab’s workflow. It connects knowledge-driven reasoning with first-principles calculations.

📜Title: LightChem: A Lightweight Domain-Specific Language Model for Molecular Property and Reaction Prediction in Chemistry 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-wd80w

3. Using Water as a Guide to Crack the Glycan Docking Problem

In molecular docking, handling flexible small molecules is already complex. Docking a glycan (a sugar chain) is even harder. Glycans are large, flexible, and have numerous conformations. Their binding sites on proteins are often shallow and flat, full of hydrophilic groups, and lack the well-defined “pockets” of traditional drug targets. This causes standard docking software to often produce poses that look reasonable energetically but are chemically incorrect.

This study offers a new way to think about the problem. The researchers focused on one question: What is in the protein’s binding site before the glycan binds?

The answer is water molecules. These water molecules aren’t just there randomly; they form a stable network of hydrogen bonds with the amino acids on the protein’s surface.

The researchers realized that the positions of these water molecules effectively create an “interaction hotspot map.” If a water molecule can form a hydrogen bond with the protein at a certain spot, then a suitable group on a ligand (like a hydroxyl group) placed in the same spot could form a similarly favorable interaction.

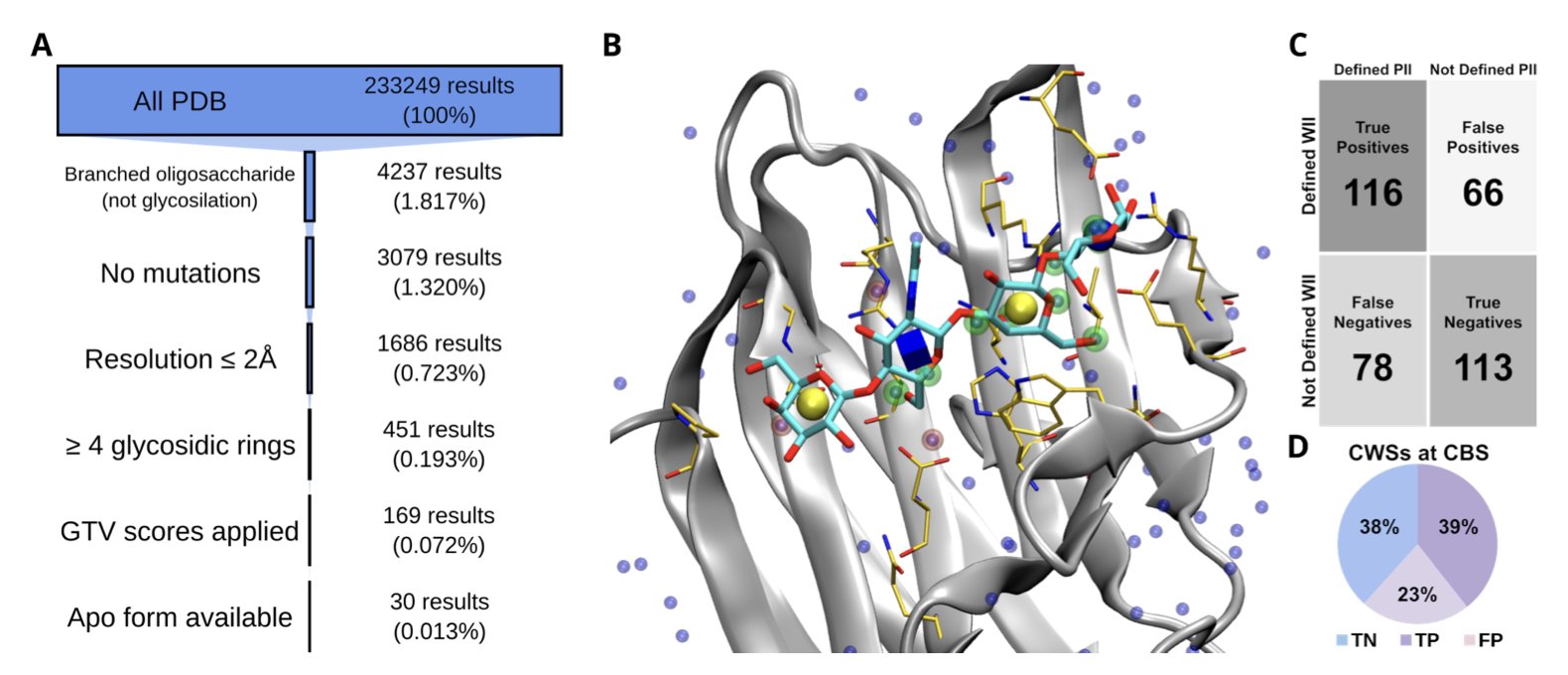

Based on this idea, they developed a docking procedure called the “WIIGA” method.

Here’s how it works: 1. First, it uses an apo protein structure, one without a bound ligand. 2. It identifies all the water molecules within the binding site and defines their locations as “Waters Ideal Interactions” (WII). 3. Then, during the docking calculation with AutoDock Vina, it adds a “bonus term” to the scoring function. If an atom on the glycan ligand lands in a WII hotspot region and can form a chemically reasonable interaction (like a hydrogen bond), that docking pose gets extra points.

This is like giving treasure hunters a map with red X’s on it. It narrows the search space and stops the program from wasting time exploring meaningless conformations.

To test their method, the researchers built a test set of 30 high-quality protein-oligosaccharide complexes. The results showed that WIIGA consistently outperformed several leading glycan docking tools, including the standard version of AutoDock Vina, Vina Carb (VC), and GlycoTorch Vina (GTV). It was more accurate at predicting the correct binding mode that matched the crystal structure.

One advantage of this method is that it only requires the structure of the apo protein. In drug discovery, it’s often easier to get the structure of the target protein by itself than the structure of it bound to a ligand. WIIGA remained robust in cross-docking tests, which more closely mimic real-world scenarios.

Even more valuable, the method also works for drug-like small molecules that medicinal chemists care about—glycomimetics. This can be used to design small-molecule drugs that target glycan-binding proteins like lectins.

The method does have its limitations. One major constraint is the conformation of the protein itself. If a protein undergoes a significant shape change when it binds a ligand (an “induced fit”), then a WII hotspot map based on the rigid apo structure might not be accurate. The test results confirmed this: using an apo structure or an AlphaFold3-predicted model led to lower docking accuracy than using an experimentally determined holo structure. This suggests that for highly flexible targets, a single crystal structure might not be enough. It may be necessary to use molecular dynamics simulations or structural ensembles to get a more complete picture.

This work provides a practical and clever tool for the difficult problem of glycan docking. It also shows that sometimes the key to solving a complex problem lies hidden in the most common and easily overlooked details, like water.

📜Title: Guided docking using solvent structure information improves the prediction of protein-glycans complexes 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-8qvgh