Table of Contents

- TEMPL is a clever benchmark that reveals many AI docking models might be memorizing data instead of understanding chemistry, setting a new, more honest standard for the field.

- Bio-KGvec2go offers a ready-to-use web service that automatically generates and provides the latest biomedical knowledge graph embeddings, freeing researchers from the hassle of maintaining and updating these complex models themselves.

- This isn’t just another AI model with a new name. By forcing the model to focus on the actual binding pocket, Tensor-DTI brings a much-needed dose of realism and robustness to drug-target prediction.

- This research turns single-cell data into sentences that an AI can read, then sends the AI to find matching passages in a vast body of literature, successfully giving rich biological meaning to cold gene expression numbers.

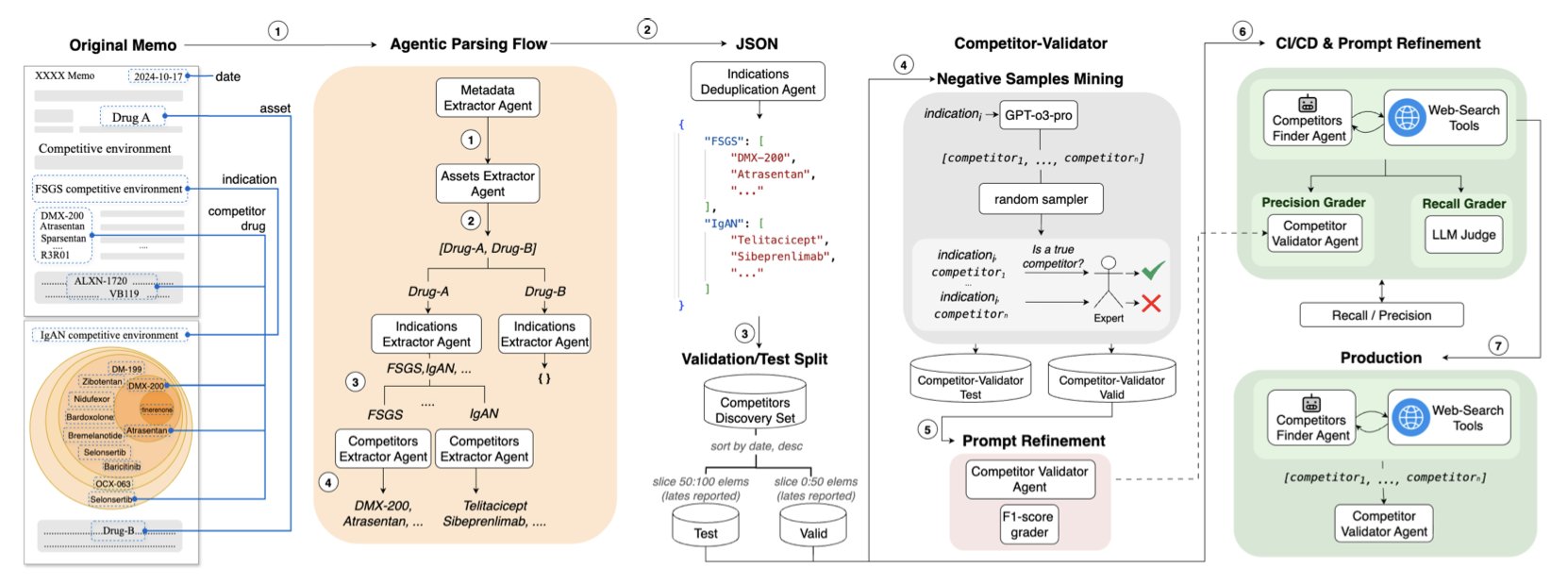

- A team of AI “Discoverer” and “Judge” agents turns competitive landscape analysis for drug assets from a multi-day manual task into an automated process that takes just a few hours.

1. TEMPL: A Reality Check for AI Molecular Docking

In computational drug chemistry, we’re flooded with new AI molecular docking models. Every paper claims its model is faster and more accurate, predicting how drug molecules “shake hands” with target proteins with unprecedented precision. But there’s a nagging question: have these AI models truly learned physical chemistry, or have they just become really good at memorizing the PDB database?

This new paper gives us a very useful reality check.

The AI Learned to Copy Homework

The new method is called TEMPL. Its principle is almost shamelessly simple. It doesn’t try to learn complex physics or chemistry. Instead, it acts like that average student in class who has a simple survival strategy: copy the homework.

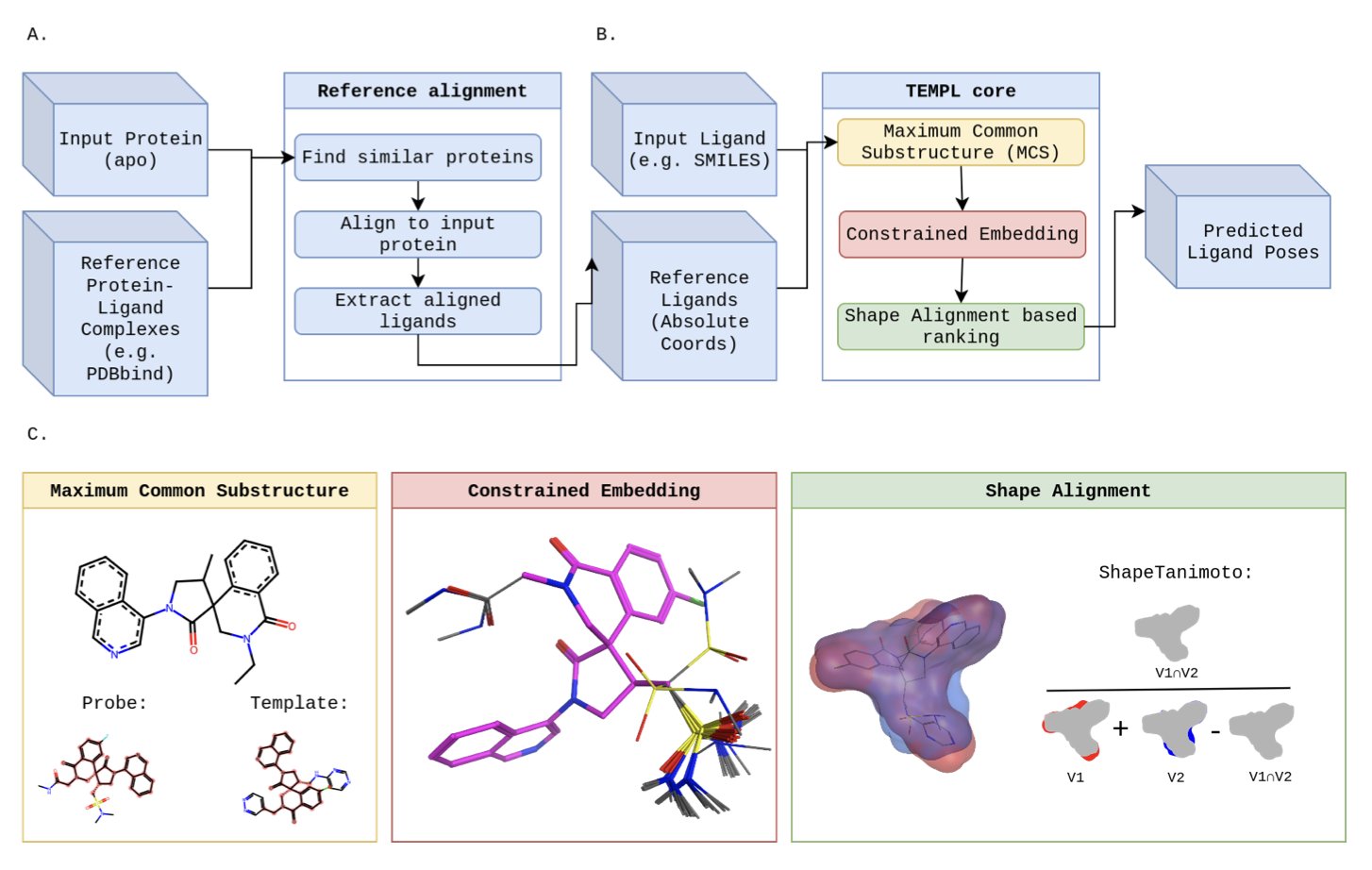

Here’s how it works:

When you give TEMPL a new molecule and ask it to predict the binding pose, it first searches a huge reference database for a molecule that looks most similar to yours and already has a crystal structure.

Then, it identifies the common chemical backbone between the two molecules. It pins this shared part down, fixing it in the same position as the original molecule.

Finally, it takes the extra parts of your molecule—the bits that are different—and just finds a comfortable spot for them nearby.

The entire process involves no energy calculations and no physics. It’s just imitation.

So, How Did It Do?

Now for the interesting part. How well did this homework-copying student perform on the test?

On a relatively simple test (the PDBBind benchmark), its accuracy was 22.1%. That’s not high, but it’s on par with some traditional docking software and even better than some deep learning models.

This is like finding out that the student who only copies homework actually passed the final exam. This likely means the test was too easy, with many questions identical to those in the practice workbook.

But on a tougher test designed to prevent cheating (the PoseBusters benchmark), TEMPL’s performance plummeted to 8.9% accuracy.

And that’s not all. The researchers found that even among the 22.1% of “correct” answers, two-thirds of the poses were physically impossible—the atoms were crammed so close together they would have collided.

What Does This Tell Us?

So, is TEMPL a good tool? Obviously not.

But it is an extremely important tool.

It sets a new, somewhat harsh, but absolutely necessary baseline for our entire field. From now on, before any new AI docking model boasts about its performance, it must first answer the question: “Did you score better than TEMPL, the model that only copies homework?”

If your model can’t beat this simple, template-based copying method, why should we believe it has learned any deep principles of physical chemistry, rather than just memorizing the training set in a more complicated way?

TEMPL is the mirror that shows whether an AI model is a true scholar or just pretending to be one.

📜Title: TEMPL: A Template-Based Protein-Ligand Pose Prediction Baseline 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-0v7b1 💻Code: https://github.com/CZ-OPENSCREEN/TEMPL

2. Bio-KGvec2go: Instantly Usable, Always-Current Knowledge Graph Embeddings

In bioinformatics, a Knowledge Graph is like a high-definition map of the complex biological world. It connects scattered points like genes, proteins, diseases, and phenotypes with their relationships, forming a vast network. Knowledge Graph Embeddings (KGE) are a mathematical way to convert each “location” on this map (like a gene) into a vector coordinate. With these coordinates, a machine can understand the relationships between them to make predictions and inferences.

This sounds great, but there’s a tricky problem: the map of biological knowledge is updated almost daily. New gene functions are discovered, and new disease associations are reported. If you use a year-old map for navigation, you might miss a new subway line or even take the wrong path. Similarly, using a KGE trained on an outdated version of the Gene Ontology (GO) will hurt the performance of your machine learning model.

For many labs, keeping up with this pace of updates is too costly. Constantly downloading new data and retraining these complex embedding models consumes a lot of computational resources and is tedious.

The Bio-KGvec2go platform was built to solve this problem. You can think of it as a central kitchen for knowledge graph embeddings.

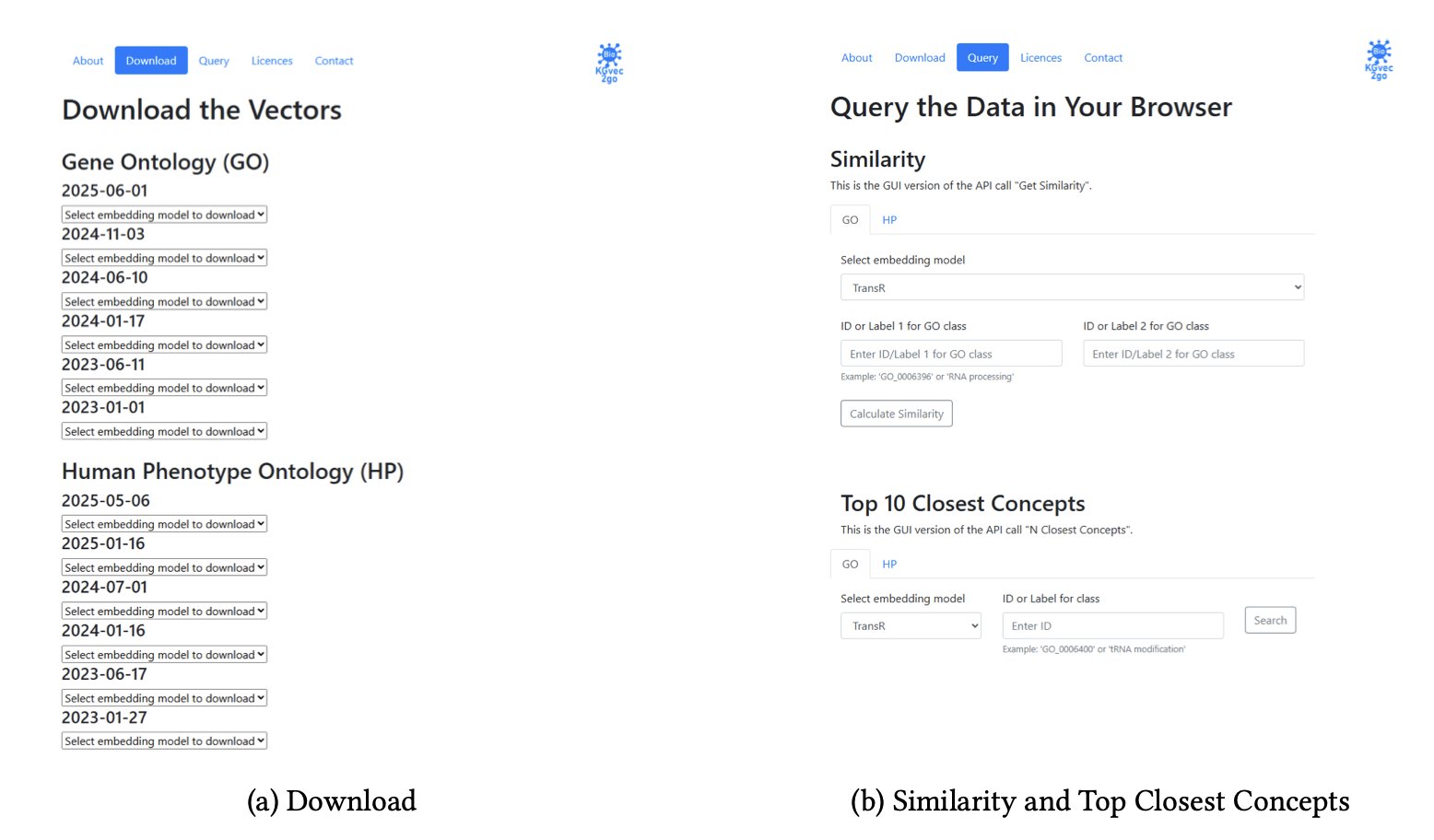

Its working principle is simple: 1. Automatic Monitoring: It acts as a sentinel, periodically checking important biological knowledge bases like GO and the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) for new releases. 2. Smart Updates: It calculates the checksum of new and old versions to confirm that the content has actually changed before proceeding. This avoids unnecessary work. 3. Batch Production: Once an update is confirmed, it automatically runs a whole suite of different KGE models, like TransE, DistMult, and HolE. Researchers know that no single model is perfect. Providing a “toolbox” of models allows users to choose the best tool for their specific research task, whether it’s predicting hierarchical relationships or associations. This is a well-informed design choice.

Ultimately, the platform offers researchers three straightforward functions:

The greatest value of this tool is that it makes this technology accessible. It allows smaller research teams without powerful computing clusters to use the latest and most advanced data representation methods on an equal footing. When barriers to data and tools are broken down, we are more likely to see breakthroughs in areas like protein function prediction and gene-disease association analysis.

The authors also plan to add more knowledge graphs and embedding models in the future and improve the user experience with features like auto-completion and spell-checking for concept names. These improvements will make an already useful tool even more powerful.

📜Title: Bio-KGvec2go: Serving up-to-date Dynamic Biomedical Knowledge Graph Embeddings 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.07905

3. AI Drug Discovery: Tensor-DTI Gets the Pocket Right

Honestly, we see new AI models claiming to transform drug discovery every week. But most of them look better in papers than they do in the lab. The problem with many models is that when they predict whether a drug binds to a target, it’s like trying to find the right keyhole by looking at an entire building. There’s too much information, and they miss the point.

But this time, Tensor-DTI seems different.

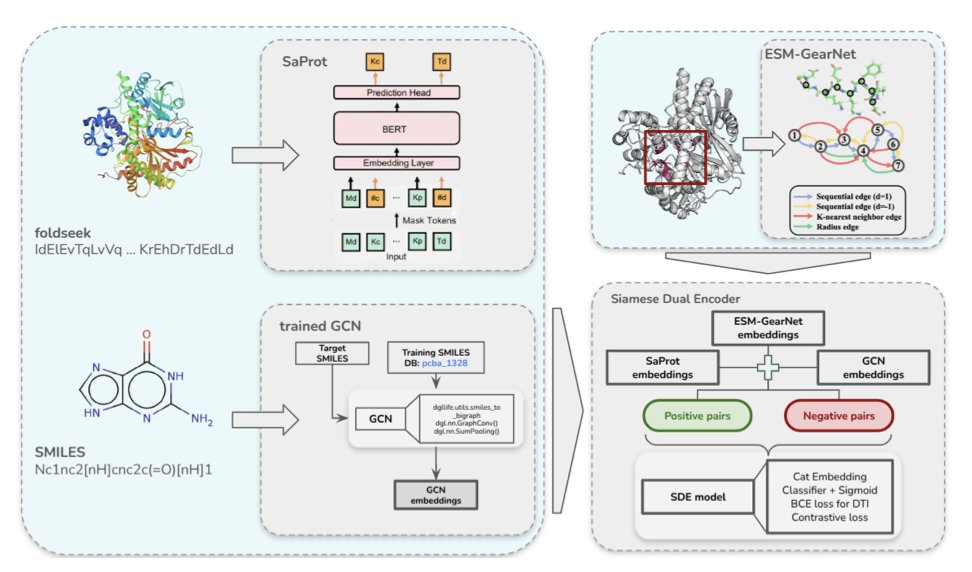

It gets to the heart of the matter: the binding pocket. A drug doesn’t just stick to the whole protein; it interacts within a small pocket with just the right shape and chemical properties. Previous models either looked only at the protein sequence (like reading a foreign language) or the entire 3D structure (like looking at a tangled ball of yarn). Tensor-DTI uses information about the pocket as a separate, important input. This is like giving a detective a precise map of the crime scene instead of asking them to wander around the entire city.

How does it do it? The researchers used what’s called a Siamese Dual Encoder architecture. It sounds fancy, but you can think of it as an expert authenticator. You give it two things at once: a drug-target pair that you know binds, and a carefully constructed “fake” pair that looks similar but doesn’t actually bind. Through contrastive learning, the model’s task is to practice “spotting the difference” until it can sharply detect the subtle chemical and spatial features that determine binding.

The benefit of this training method is that the model is forced to learn the underlying principles of physical chemistry, rather than memorizing superficial patterns that can be misleading.

What were the results? It outperformed existing models on several standard datasets like BIOSNAP and BindingDB. But that’s not what excites me. Most importantly, it also performed well on “low-leakage” datasets like PLINDER. These datasets are specially curated to prevent models from cheating by “remembering” drugs or targets they saw in the training set. Success on these shows it has a genuine ability to predict something new.

What’s more, this method isn’t just for small molecules. The authors showed it works just as well for predicting peptide-protein and even protein-RNA interactions. In today’s drug development landscape, this greatly expands its potential applications. From ADCs to RNA therapies, there’s a need for more general prediction tools like this.

Of course, there’s still a long way to go from a neat computational model to a tool that can truly guide synthesis and lead to new drugs. But Tensor-DTI is at least on the right track—it makes AI think more like chemists and biologists do about drug action. It’s no longer a black box but gives us a more interpretable view, telling us why an interaction might happen. And that is what researchers on the front lines really want from AI.

4. AI Reads Papers to Make Single-Cell Data Speak

Anyone who has worked with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data knows the feeling of being both excited and frustrated. You have a huge, colorful heatmap in front of you, with thousands of cells neatly organized into different clusters. It’s cool, but what’s next? What’s the real difference between cell cluster A and cluster B? What roles do they play in the tissue? How are they related to the disease you’re studying? That heatmap alone can’t answer these questions. We’re holding a rich book written in a language we don’t understand.

This new paper attempts to give us a “Rosetta Stone” to decipher this book.

Turning Cells into Sentences

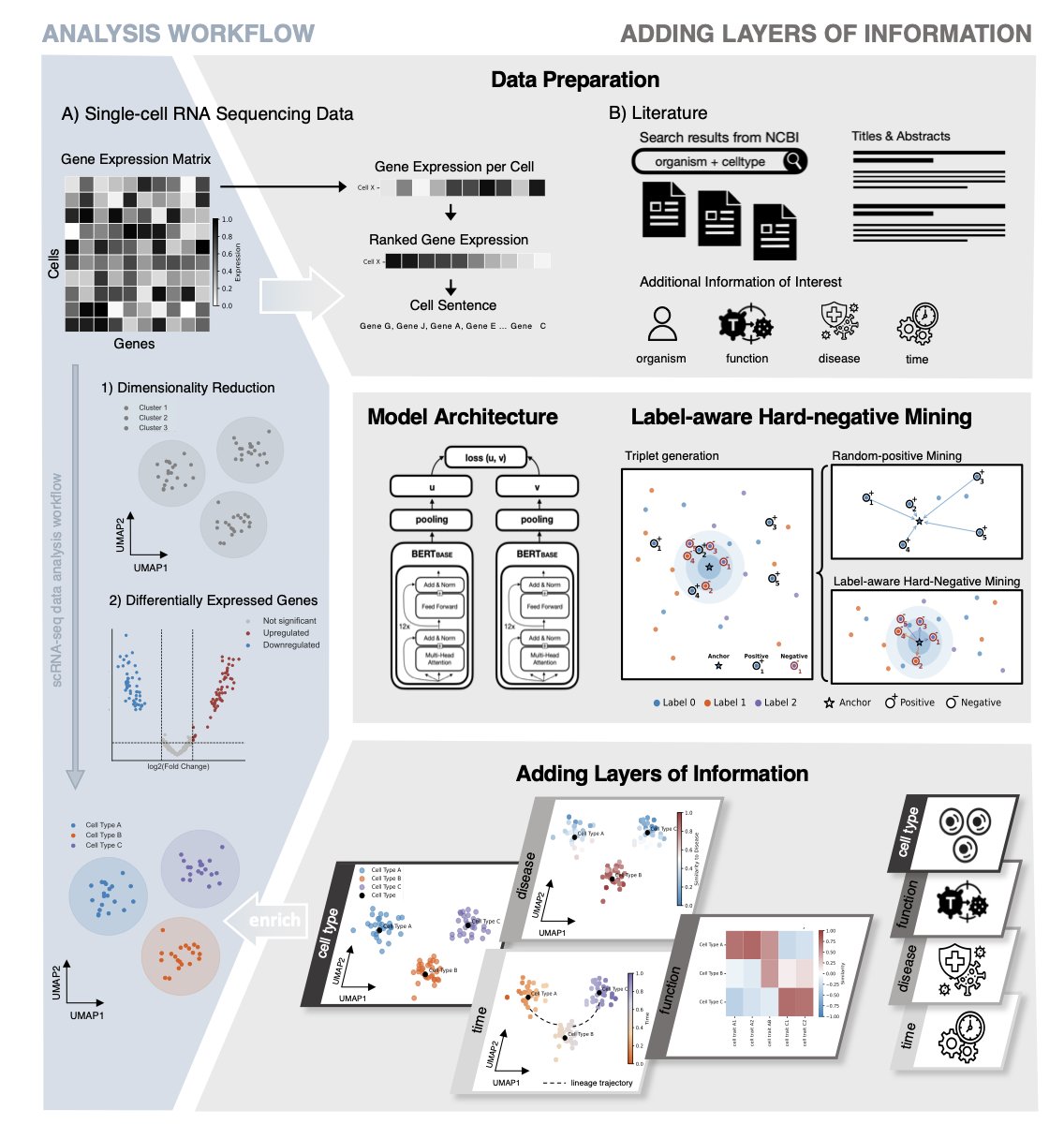

The authors’ idea is clever. Instead of building another complex black-box model that tries to find meaning directly from gene expression values, they took a different approach. Can we translate the language of cells into a language for which we already have massive text corpora—the language of human scientific literature?

Here’s how they did it:

First, they turned each cell into a unique “sentence.” This sentence is composed of the genes with the highest expression levels in that cell, arranged in descending order. They also add metadata, such as the tissue of origin and the developmental stage of the cell.

Second, they trained a pair of “twin” AI models. You can think of them as two students studying together. One student (Model A) specializes in reading the “cell sentences” generated from countless cells. The other student (Model B) reads a vast number of PubMed paper abstracts.

The training goal is that when Model A reads a cell sentence describing a “cytotoxic T cell,” the “concept” it forms in its mind must be as close as possible to the “concept” Model B forms when reading a paper abstract discussing “cytotoxic T cells.” Through this contrastive learning, the two models learn to think in the same “language.”

From Data to Insight

Once this system is trained, something amazing happens.

You give it a new, unknown cell. It translates it into a “sentence” and then finds where that sentence should be on the “semantic map” built from millions of scientific papers.

This method essentially overlays a thick layer of knowledge, accumulated from decades of scientific literature, on top of our raw, thin single-cell data. It doesn’t create new knowledge, but it builds a bridge connecting our new experimental data with the vast repository of existing human knowledge.

Of course, it has limitations. Its capabilities are capped by the quality and breadth of the existing literature. If a completely new biological phenomenon has never been reported, it naturally has nothing to link it to.

But as a hypothesis-generation engine, it is powerful. It frees us from tedious manual annotation and literature searches, allowing us to move more quickly from “seeing the data” to “understanding the data.”

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.23.671699v1

5. AI Due Diligence: 2.5 Days of Work Done in 3 Hours

Anyone who has worked in biotech investing or business development at a pharmaceutical company knows that “due diligence” is an uphill battle. This is especially true for mapping the “competitive landscape.” You have to sift through clinical trial databases, company reports, press releases, and even social media to find every drug in development for the same indication.

The process is like conducting a census in a huge, chaotic, and ever-changing city where information is overwhelming and language is mixed. It’s painfully slow and prone to errors. We’ve thought about using AI to help, but if you try, you’ll find that general-purpose tools like Perplexity have a disappointingly low recall; they miss many key competitors.

This new paper presents a practical AI system that actually solves this problem.

You Don’t Need One AI, You Need a Team

The authors’ thinking is clear. They didn’t try to train an all-powerful “super AI.” Instead, they did something that makes more sense in the real world: they built a team.

This team has two core members:

First is the “Discoverer” agent. You can think of it as a junior analyst with endless energy. Its job is to use web searches and multi-step reasoning to dig up every drug related to the target indication on the internet. Its strength is its focus on the highest possible recall, leaving no stone unturned.

But the result is that the information it brings back is inevitably mixed with irrelevant, outdated, or even completely wrong items.

So, the second member comes in.

The second is the “Judge” agent. This is an AI specially trained for fact-checking. You can think of it as an experienced senior partner with a sharp eye. Its sole task is to review the long list submitted by the”Discoverer” and mercilessly weed out all false positives and AI “hallucinations.” Its goal is the highest possible precision.

So, How Did It Do?

When this “cop and judge” duo gets to work, something remarkable happens.

The researchers didn’t just test their system on academic datasets. They did something solid: they turned a company’s unstructured due diligence memos from the past five years into a standardized evaluation database. Then, they tested their system against this real-world exam.

The result was that their system’s recall surpassed that of existing tools like OpenAI and Perplexity.

But that’s not the most important part. The key was a real-world case study from a biotech venture capital fund. In the fund’s daily workflow, it took an analyst an average of 2.5 days to complete one competitive landscape report.

Using this AI system, the time was cut down to 3 hours.

This is not a 10% or 20% efficiency gain. It’s a leap of an order of magnitude.

This work is not another distant story about what AI might do someday. It is an engineering solution that can be deployed now to solve one of the biggest pain points in our daily work. It won’t replace analysts, but it will free them from repetitive, tedious information gathering, allowing us to invest our valuable time and intellect in higher-level strategic thinking.

📜Title: LLM-Based Agents for Competitive Landscape Mapping in Drug Asset Due Diligence 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.16571