Table of Contents

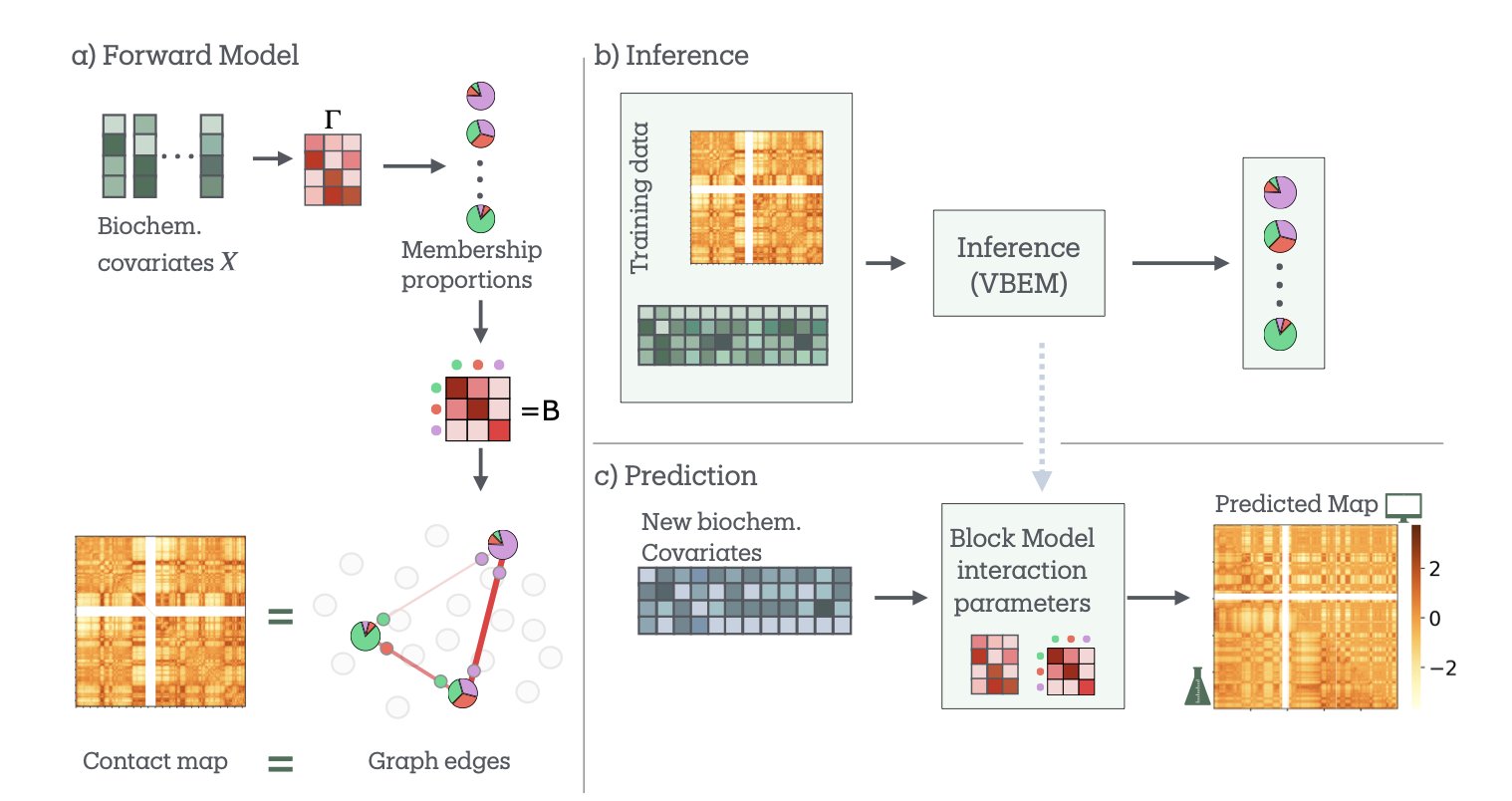

- The bioSBM model integrates epigenetic data into a stochastic block model, providing a new tool for predicting 3D chromatin structure and understanding its biochemical regulation.

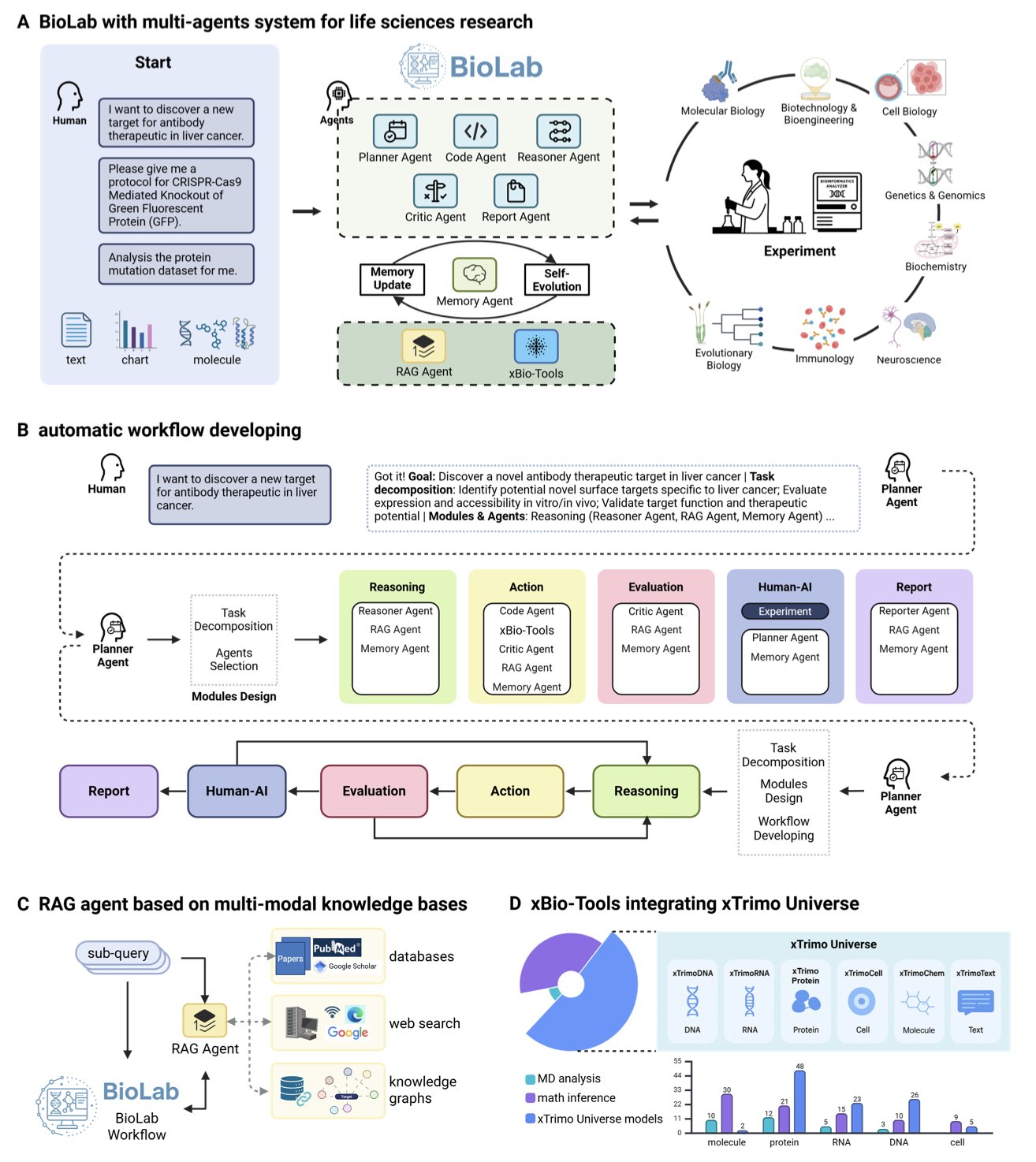

- BioLab integrates multiple specialized foundation models and agents to achieve the first end-to-end, fully autonomous antibody design, from target discovery to wet lab validation, successfully optimizing Pembrolizumab.

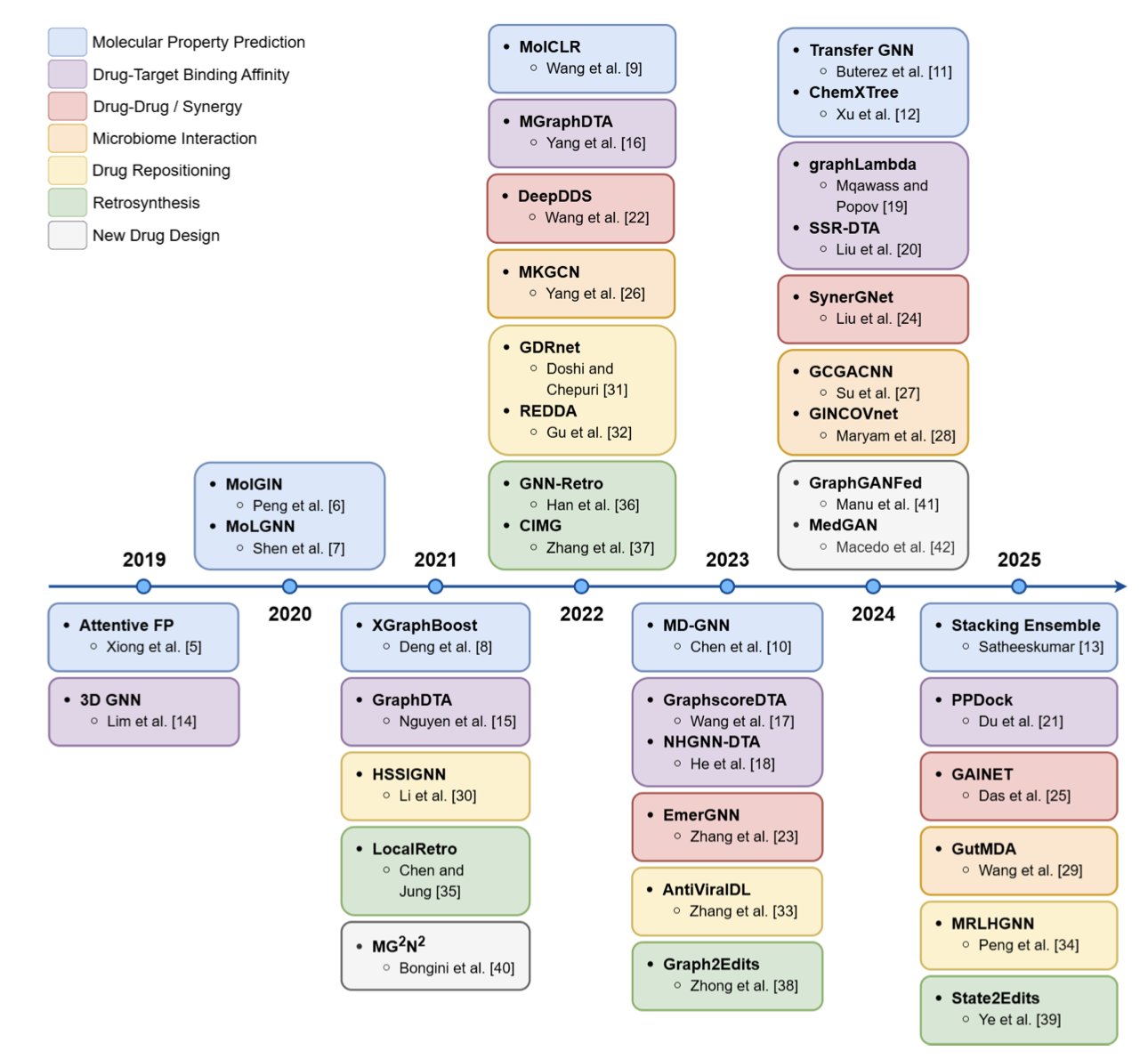

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are being used in all stages of drug discovery, from target identification to molecular design, but they must overcome challenges in data, modeling, and interpretability to be truly effective.

1. bioSBM: Using a Graph Model to Connect Epigenetics and the 3D Genome

If you study 3D genome structure, you probably work with two sets of maps. One comes from Hi-C data, which shows you the “road network” of the genome—which DNA segments are physically close to each other. The other comes from epigenetic data like ChIP-seq, which tells you the “building types” along each road—for instance, where the active promoters (commercial districts) and silent heterochromatin (industrial zones) are. We’ve always wanted to know the relationship between these two maps. Why does the road network connect different functional areas the way it does?

Now, researchers have developed a new model called bioSBM to try and answer this question.

At the model’s core is the Stochastic Block Model (SBM). SBM is a classic tool in network science that works on a simple principle: it groups nodes in a network (in this case, genomic regions) based on their connection patterns. For example, nodes in group A might be tightly connected to each other but rarely connect to nodes in group B. In the genome, this can help us find communities like Topologically Associating Domains (TADs).

The clever part of bioSBM is that it doesn’t just look at the “who connects with whom” network information. It also incorporates the second map—the biochemical features (like histone modifications)—as covariates. When the model decides whether two genomic regions should interact, it considers not only their past interaction frequency but also their “identity.” Are they active enhancers or repressed regions? It’s like a city planner who looks at both traffic flow and land-use functions to design a road network.

The model has another key feature called “mixed memberships.” Traditional classification methods are rigid; a genomic region is either in compartment A (active) or B (inactive). But biology is more complex. A gene might be active under some conditions and silent under others. bioSBM allows a genomic region to belong to multiple communities at once. For example, it might be 70% “active transcription zone” and 30% “polycomb-repressed zone.” This is much closer to reality.

To test the model, researchers applied it to the well-known GM12878 cell line. The results were good. The model not only identified the traditional A/B compartments but also found 7 more detailed biological communities with very clear functional annotations (like their relationships to CTCF binding sites and enhancers). It’s like upgrading from a black-and-white map to a full-color functional zone map.

Its predictive power is the most impressive part. The researchers trained the model on data from some chromosomes and then asked it to predict the Hi-C interaction map of a chromosome it had never seen. The results were quite accurate. They also ran a more challenging experiment: using data from one cell line to predict the structure of a completely different one (HCT116), where a key structural protein, RAD21, had been knocked down. Even then, bioSBM performed robustly.

This shows that bioSBM isn’t just fitting data; it has learned some of the underlying rules connecting epigenetics and 3D structure. Understanding these rules is very important for drug development. If we can accurately predict how a change in an epigenetic modification will affect the 3D structure and, in turn, the expression of an oncogene, we can design more precise epigenetic drugs. This model gives us a powerful, interpretable computational tool to move in that direction.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.14425v2

2. BioLab: An AI Agent System for End-to-End Drug Discovery

An AI-designed antibody performed better in experiments than Merck’s Keytruda® (Pembrolizumab).

It sounds like science fiction, but a new preprint from the BioLab team has made it a reality. As a research scientist, I always get excited when I see work that perfectly closes the loop between computational design and wet lab validation.

This wasn’t achieved by a single Large Language Model (LLM). BioLab’s architecture is more like an efficient research group. The system has eight AI agents, each with a specific role. For instance, a “PI” Planner agent sets the overall research plan, a “postdoc” Reasoner agent executes specific tasks, and even a “reviewer” Critic agent evaluates and revises the results. They share information and iterate through a Memory Agent, making the whole process well-organized.

The “brains” of these agents are not generic. They are based on a model library called xTrimo Universe, which contains 104 foundation models trained specifically for life sciences, covering proteins, RNA, DNA, and cells. You wouldn’t ask a historian to solve a protein structure, and here, each task is handled by the most suitable “expert” model. This specialization allowed BioLab to outperform general models like GPT-4 on biomedical reasoning tasks like PubMedQA.

Of course, benchmark scores are secondary. The real test is solving a real-world problem.

The researchers gave BioLab a tough assignment: design an antibody targeting macrophages from scratch. BioLab autonomously completed the entire computational workflow, from mining the literature for targets to multi-objective antibody optimization. Through molecular dynamics simulations, the system not only found variants with better affinity but also revealed the structural mechanisms behind the improvement—something drug developers value highly.

The most critical step was closing the loop with validation. No matter how good a computational design is, it has to be tested on the bench. The team expressed and purified the optimized antibodies (Pem-MOO-1, Pem-MOO-2) and tested their activity. The results showed that the new antibodies bound to PD-1 with IC50 values of 0.01–0.016 nM, better than the parent Pembrolizumab’s 0.027 nM.

The data doesn’t lie. The AI-designed molecules truly surpassed a blockbuster drug in biological activity. Functional experiments also confirmed that the new antibodies not only bind tighter but also perform better in blocking signaling pathways and across multiple performance metrics.

BioLab’s work demonstrates an AI-native research paradigm. It shows us that combining multiple “expert” AIs, letting them autonomously propose hypotheses, design experiments, analyze results, and finally validate them in the wet lab, is a viable path. This is no longer just computational simulation; it’s true end-to-end scientific discovery.

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.09.03.674085v1

3. The GNN Drug Discovery Landscape: Progress, Models, and Challenges

Anyone in drug development knows that a molecule is itself a graph. Atoms are nodes, and chemical bonds are edges. In the past, we had to compress this 3D structural information into a 1D SMILES string, a process that inevitably loses information. The arrival of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) changed the game. They don’t need this compression and can learn and reason directly on the molecular graph, making them a tool you can’t ignore in drug discovery.

This review by Katherine Berry and Liang Cheng does a great job of summarizing how GNNs are being used in our field.

GNNs first proved themselves in molecular property prediction

This was the first area where GNNs succeeded, and it’s relatively easy to understand. It involves tasks like predicting a molecule’s ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) properties. The model learns from a large number of known molecules to find correlations between structure and properties. Early models were simple, but later ones like Attentive FP and MolGIN went a step further. They introduced an attention mechanism, allowing the model to decide for itself which functional group in a molecule is most important for a specific property, like toxicity. This is a bit like an experienced chemist who can glance at a structure and spot the key features.

Predicting drug-target binding affinity is the really tough problem

Predicting whether a molecule will bind to a protein target, and how strongly, is central to drug discovery. The difficulty here is that you have to consider not only the structure of the drug molecule but also the 3D structure of the protein’s binding pocket. It’s like trying to figure out if a key (the drug) will fit a lock (the target); you need a clear view of both. Models like GraphDTA and MGraphDTA started trying to merge these two types of information. They create separate graph encodings for the drug and the target protein and then learn the interaction between them. The goal of this research is to have computers find the one “chosen” molecule from massive libraries faster and more accurately than high-throughput screening.

Drug combination and synergy prediction

In treating complex diseases like cancer, a single drug is often not enough; combination therapy is the standard. But when you put two drugs together, will the effect be synergistic (1+1>2) or antagonistic (1+1<2)? This is very hard to predict. Models like DeepDDS and SynerGNet use GNNs to analyze complex biological networks, such as gene regulatory or protein-protein interaction networks. They try to understand how drugs affect the cell at a systems level to predict the outcome of drug combinations. This is critical for developing new combination therapies.

GNNs are used for much more

The review also mentions GNN applications in other areas. For example, predicting interactions between drugs and the gut microbiome, which is useful for understanding personalized medicine. There’s also drug repositioning—finding new uses for old drugs—where GNNs can find new possibilities by analyzing networks of drug-disease associations. GNNs are even useful in retrosynthesis, helping chemists design better synthetic routes.

The challenges are still serious

Although GNNs look promising, those of us on the front lines know there’s a long way to go from a paper to a practical application.

The first problem is data. “Garbage in, garbage out” is especially true in AI. Many public bioactivity datasets are full of noise, and the amount of data isn’t always sufficient. We need more high-quality, diverse experimental data to feed these models. Otherwise, a trained model might just look good on paper but fail in real-world chemical space.

The second is the models themselves. There is a huge variety of GNN architectures, and there’s no consensus on which one is best for a specific chemical or biological problem. This leads to a lot of “alchemy”—endless tweaking of model parameters and structures without systematic guidance.

The last, and most critical, challenge is interpretability. The model tells you a molecule has high activity. Why? Which substructure played the key role? If the model can’t answer this, it’s a black box to a medicinal chemist. We can’t learn from it or use its judgment to rationally design the next, better molecule. We are doing science, not fortune-telling. If we can’t open this black box, AI will only ever be a screening tool, not a driver of true innovation.

This review provides a clear map of GNNs in drug discovery. GNNs have evolved from an academic concept into an increasingly important part of the drug development toolbox. The next steps are clear: gather better data, design smarter models, and find a way to make the models talk.

📜Title: A Survey of Graph Neural Networks for Drug Discovery: Recent Developments and Challenges 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.07887