Table of Contents

- Researchers have developed an AI system combining a large language model and tree search. It writes and optimizes code like an expert, systematically discovering scientific computing methods that surpass human performance.

- This isn’t just another Q&A bot. STELLA is an AI agent that can evolve like a research team and even “invent” new tools on demand.

- The new BioML-bench benchmark shows that the performance bottleneck for AI agents in biomedicine isn’t the model itself, but the underlying engineering and framework support.

1. AI That Automates Programming and Systematically Outperforms Human Experts

In scientific research, we spend a lot of time writing and debugging code to process data. The process is full of trial and error, especially when developing new analytical methods. We often rely on intuition and experience to combine different algorithmic modules. A new paper presents an AI system that aims to turn this into a systematic, automated engineering problem.

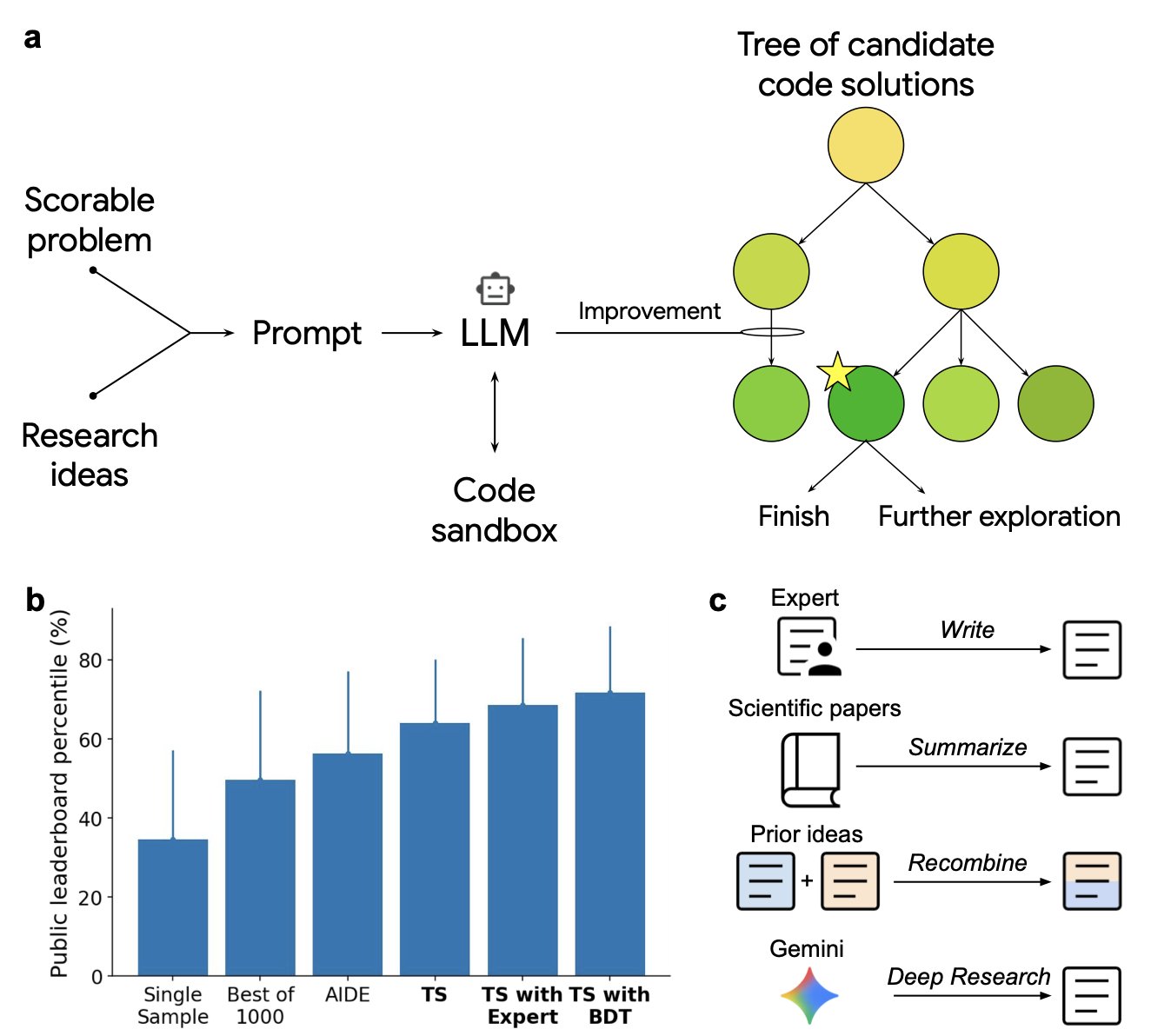

The system’s working principle is quite direct. It consists of two core components: a Large Language Model (LLM) and a tree search (TS) algorithm.

You can think of the LLM as a junior researcher who is very knowledgeable but disorganized. You give it a goal, like “find a better batch correction method for single-cell data,” and it draws inspiration from a huge volume of literature and codebases to propose a pile of possible code snippets or improvement ideas.

The tree search algorithm, on the other hand, plays the role of a rigorous senior scientist. It takes all the ideas generated by the LLM and organizes them into a giant “decision tree.” Then, it methodically explores every branch of this tree, combining idea A with idea B to test performance, then combining idea A with idea C. Each step is evaluated with a clear, quantitative metric.

This “generate and search” model allows the AI to do more than just write code; it systematically explores a vast “solution space.” It can uncover non-intuitive combinations of solutions that human researchers might miss due to fixed mindsets or limited energy.

Let’s look at its performance in a few challenging fields.

In single-cell data analysis, building an efficient analysis pipeline is notoriously difficult. The researchers found that this AI system independently discovered 40 new analysis methods, beating all human-submitted methods on a public leaderboard. For example, by cleverly combining two known batch correction methods, it created a hybrid strategy with better results. A person might have thought of this, but the AI can exhaust all possible combinations and tell you which one is best.

It performed equally well in epidemiology. To forecast COVID-19 hospitalizations, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses an ensemble model, which combines predictions from multiple independent models to improve accuracy. This AI system independently generated 14 new forecasting models, each outperforming the CDC’s entire ensemble model. This shows it found better ways to combine signals and assign weights for classic problems like time-series forecasting.

One application I found interesting was in zebrafish neuroscience research. The system not only surpassed all existing methods in predicting neural activity but also easily integrated a complex biophysical simulator into its solution. In real-world development, making code call a non-standard, domain-specific tool is often tricky. But this AI managed it seamlessly, like an assistant you can tell to use a specific precision instrument, who then figures out how to use it and incorporate it into the entire experimental workflow.

The point of this tool isn’t to replace scientists, but to free us from tedious code optimization and method exploration. It’s like a tireless postdoc with infinite energy, who can test thousands of parameter combinations 24/7 and has “read” every relevant paper in the field.

It transforms empirical method development into a search task that can be executed by machines at scale. For fields like drug discovery, which require finding patterns in massive, complex datasets, this acceleration means we can validate hypotheses and iterate on ideas much faster.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.06503

2. STELLA: The Self-Evolving AI Research Agent That Builds Its Own Tools

Honestly, whenever I see another “breakthrough” biomedical AI model, my first reaction is a bit of skepticism. We’ve seen too many that were all sizzle and no steak. But STELLA is a little different. It seems to have really figured something out.

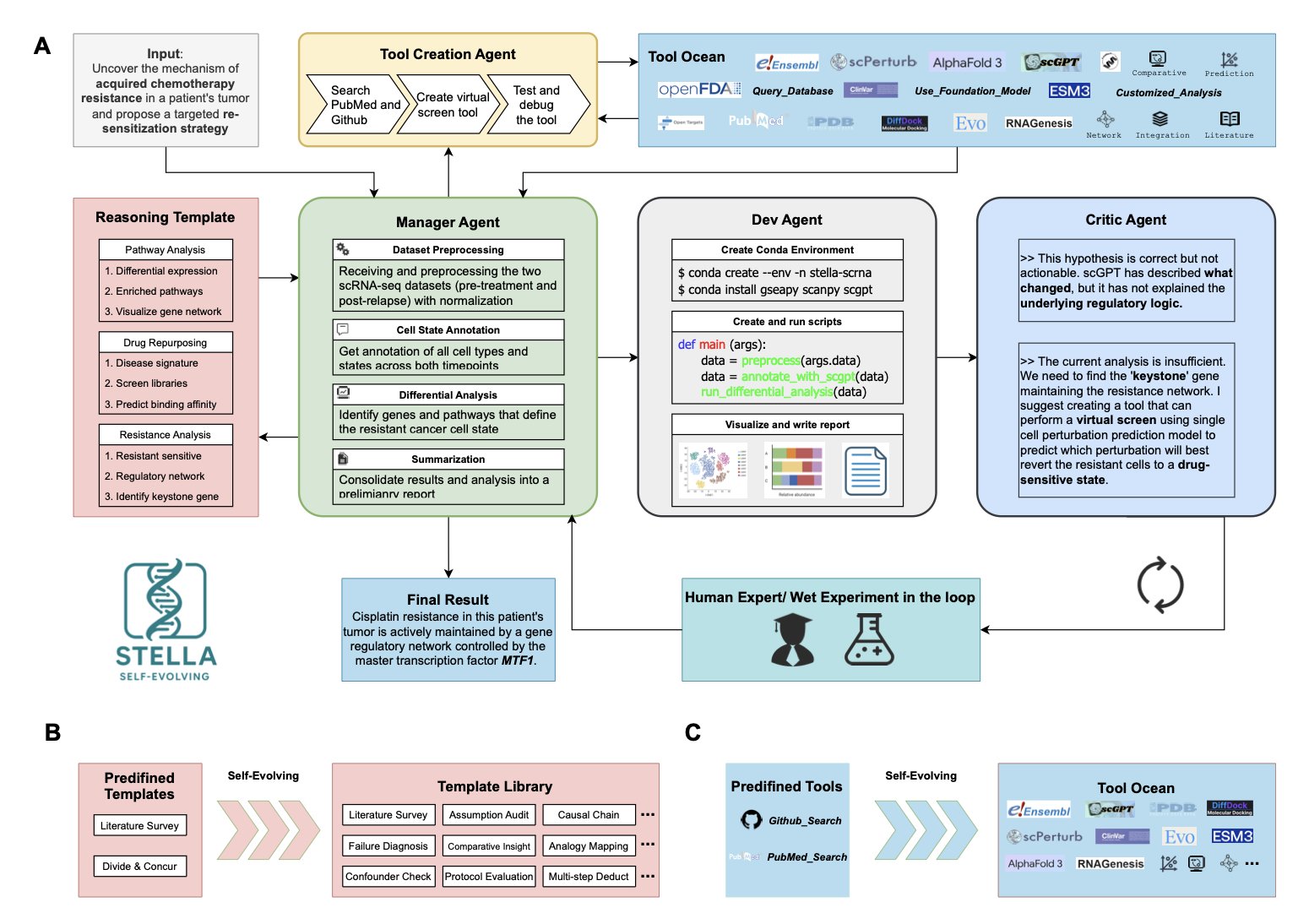

Most AI agents on the market are basically interns equipped with a fixed Swiss Army knife. They can use existing tools, like querying PubMed or running AlphaFold. But as soon as they encounter a problem that requires a tool not in their toolbox, they’re stuck. STELLA is different. It doesn’t just have a toolbox; it is a toolmaker.

The essence of this system lies in its internal “organizational structure.” The researchers designed a closed-loop system with four collaborating agents, which sounds like a miniature R&D team: 1. Manager: Acts like a project lead (PI), breaking down a complex biological problem into small, executable tasks. 2. Developer: This is the graduate student or postdoc who does the work. It takes a task and writes code or calls a library to solve it. 3. Critic: This role is very realistic—it’s like that colleague in the lab who is always finding fault but whose critiques you have to respect. It rigorously reviews the developer’s plans and results, offering suggestions for improvement and ensuring the project stays on track. 4. Tool Creator: This is the key part. When existing tools can’t solve a problem, this “master” can write a new script or tool on the spot. It then adds it to a shared library called the “Tool Ocean” for everyone to use in the future.

This ability to “build weapons while fighting the war” is what makes it so powerful. In a case study on chemotherapy resistance, STELLA didn’t just analyze gene expression data. It realized it needed a specific virtual screening tool to test a hypothesis, so it built one itself. It then used that tool to successfully identify the key driver of resistance—the transcription factor MTF1. For people in drug development, the implication is clear. It bridged the gap between “thinking” and “doing” by building the necessary tool itself.

Even more impressive is that this thing actually “grows.” In benchmark tests, it repeatedly attempted tasks, improving its score from 14% to 26%. This isn’t simple memorization. Through constant trial and error, it optimized its “Template Library,” so the next time it encounters a similar problem, it performs better.

So, my feeling is that STELLA is no longer just a tool. It’s more like a junior research assistant with an extremely strong ability to learn. It’s not passively answering questions anymore. It’s actively learning how to solve problems better and even creating the means to solve them. We may still have a long way to go before we have a true “AI scientist,” but STELLA undoubtedly shows us a clearer, more practical path forward.

3. AI Agents for Drug Discovery Are Failing? New Benchmark BioML-bench Reveals Engineering Shortfalls

Lately, we hear a lot of talk about how AI agents are going to upend scientific research. It sounds great, but as people working on the front lines of R&D, we always ask: how does this stuff actually perform on real, complex biomedical research tasks? It’s easy to make a cool demo, but getting it to reliably solve a real problem from start to finish is another story entirely.

Now, a team has finally built a “testing ground” to rigorously evaluate the true capabilities of these AI agents. This testing ground is BioML-bench.

It’s not a simple question-and-answer test. It gives an AI agent a complete project task, like, “Here is a bunch of protein sequence data. Please build a predictive model, evaluate its performance, and then submit the prediction results.” The entire process requires the agent to understand the task, parse the data, write code, train a model, and finally output a result that can be measured by a public standard. This is a real-world workflow. The benchmark covers four core areas: protein engineering, single-cell omics, biomedical imaging, and drug discovery.

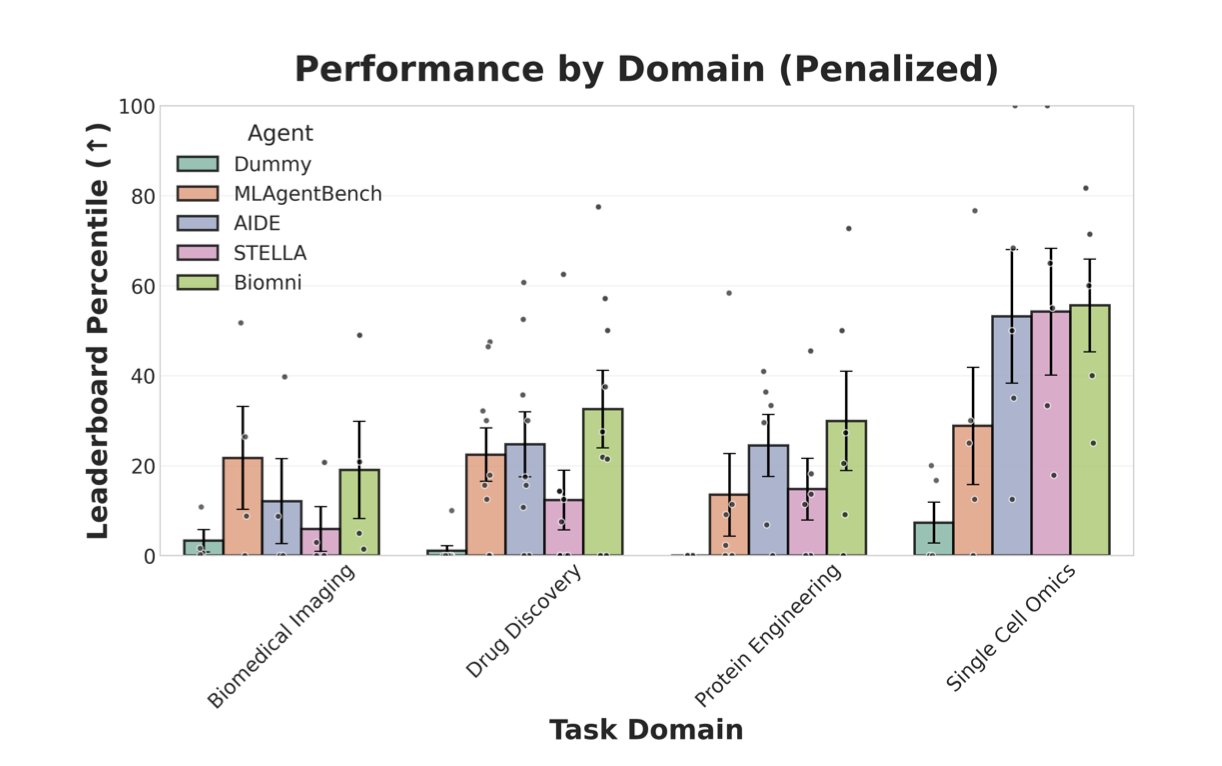

The researchers tested four AI agents: two “specialists” in biomedicine (STELLA, Biomni) and two “generalists” (AIDE, MLAgentBench).

The results were a bit sobering. Overall, none of the agents performed as well as the human-set baselines. And unexpectedly, the “specialists” showed no decisive advantage. This suggests that simply feeding an agent biomedical knowledge doesn’t guarantee it can do the job well.

So which agent performed better, and why?

The generalist agent AIDE got a high score on a protein engineering task. Its winning formula wasn’t some mysterious biological intuition, but solid machine learning engineering skills. It didn’t just throw protein sequences into a model as a string of letters. Instead, it performed detailed feature engineering, calculating various evolutionary and biophysical numerical values from the raw sequences. It also used advanced techniques like model stacking to improve prediction accuracy. This is exactly what an experienced data scientist would do.

Conversely, the failure cases were also very instructive. Most of the mistakes the agents made weren’t due to flawed logic or incorrect ideas, but to very practical engineering problems. For example, the code would run out of memory; a script had a bug that went unnoticed, leading to a silent incorrect result; or the program would crash upon encountering an exception.

What does this tell us? The biggest weakness of current AI agents may not be their brain (the large language model), but their body and limbs—what we call the “scaffolding.” This scaffolding is the entire support system responsible for managing task execution, handling code errors, and allocating computational resources. If this system is fragile, even the most powerful “brain” can’t reliably complete complex tasks.

So, the greatest value of the BioML-bench work is that it pulls our attention away from the hype about AI agents and back to the most fundamental and important engineering issues. The next step for us should probably not be to train a model that understands biology better, but to build a more stable and robust execution framework. A scientist also needs a well-equipped, well-managed lab to produce results. For an AI agent, this “lab” is its engineering scaffolding.

The good news is that the researchers have made BioML-bench available as a package you can install directly with pip, complete with tutorials. This means anyone can use it to test and improve their own AI agents. This is the right way to move the field forward: establish standards, test openly, and iterate quickly.

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.09.01.673319v1