Table of Contents

- AlphaFold has mapped the structures of thousands of hydrophobic proteins, revealing new features and evolutionary branches, but predicting their dynamic self-assembly remains a key challenge.

- OmniPert merges the separate worlds of gene editing and drug screening on a virtual lab bench at single-cell resolution, giving us an unprecedented view of cellular responses.

- ADGSyn achieves new highs in performance and a leap in efficiency for anticancer drug synergy prediction, thanks to its innovative dual-stream attention GNN and AMP training.

1. AlphaFold Uncovers the Secrets of Fungal Hydrophobins: A Structural Blueprint and Its Challenges

Fungal hydrophobins are interesting little proteins. You can think of them as nature’s Teflon, helping mushrooms stay clean after a rain. Their core ability is to self-assemble into a stable, water-repellent film at water-air or water-solid interfaces. This gives them huge potential in biomaterials, coatings, and even drug delivery. The problem is, their sequences are highly diverse, which has always made studying their structures tricky.

Now, AlphaFold is on the scene. We all know how powerful it is at predicting the structure of single proteins. This new study wanted to see what would happen when AlphaFold was used on hydrophobins.

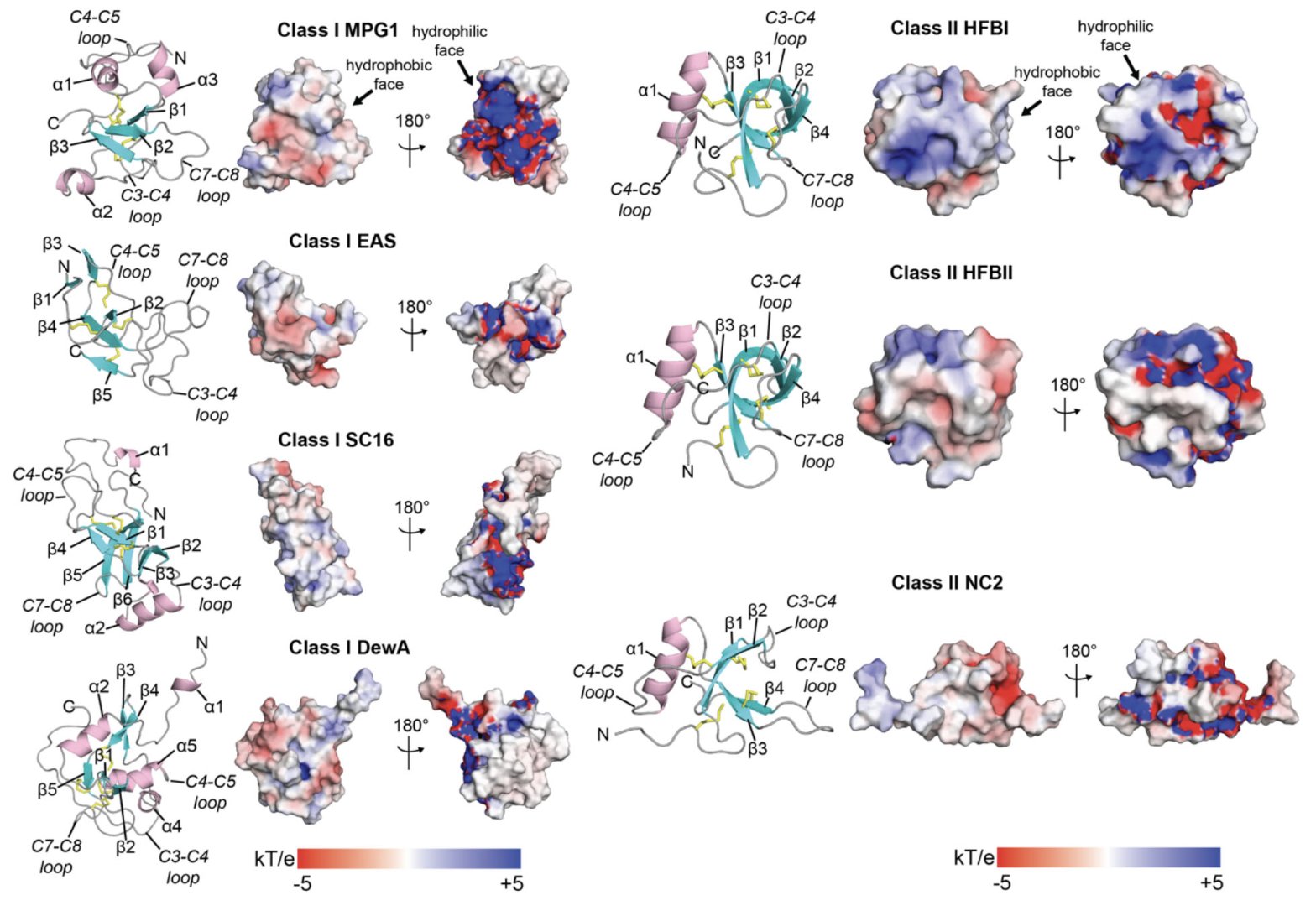

First, the researchers ran a benchmark test to see if AlphaFold’s predictions were reliable. The results were as expected: for the conserved β-barrel core structure in hydrophobins, AlphaFold’s predictions were very accurate. This core is like the load-bearing wall of a house, defining the protein’s basic shape.

But the interesting part is the flexible, functional loop regions. In these areas, AlphaFold’s prediction confidence (pLDDT score) dropped significantly. This doesn’t mean AlphaFold failed. It was actually telling us, “Hey, this part of the structure is unstable, it’s probably flexible.” For researchers, this is key information. These flexible regions are often the “business end” of the protein, where it interacts with other molecules or senses environmental changes. Knowing what’s stable and what’s flexible is the first step in designing new functional proteins.

The most exciting part of this work is that they analyzed over 7,000 hydrophobin sequences at once. This wasn’t just looking at one or two proteins; it was like drawing a “structural map” of the entire family. Through this large-scale modeling, they clearly divided these proteins into six distinct evolutionary clades and built a detailed phylogenetic tree. It’s like rewriting the family tree for this protein family from a genomic perspective. It lets us see the subtle structural differences between branches and infer how their functions diverged.

Along the way, they also found some “unconventional” hydrophobins. For example, some proteins had a long “tail” at their N-terminus, some had an extra disulfide bond (for a total of five pairs), and some even had multiple hydrophobin domains linked together (“polyhydrophobins”). Each of these unusual features could correspond to a special function. An extra disulfide bond might make a protein much more stable. That long tail might act like a “gripper” to bind to other proteins. These findings give us new ways to understand and engineer hydrophobin diversity.

Of course, AlphaFold isn’t a silver bullet. The researchers admit that when it comes to the core function of hydrophobins—self-assembly and membrane binding—the current model struggles. AlphaFold was designed to predict single protein structures; it doesn’t know how these individual units are supposed to line up like tiles on a floor. This is a common challenge in computational structural biology: how to predict how the whole machine works from the blueprint of a single part.

The path forward is clear. We need to combine AlphaFold’s static structure predictions with tools that can simulate dynamic processes, like molecular dynamics simulations, or integrate more experimental data to truly unlock the secrets of hydrophobin self-assembly.

📜Title: AlphaFold modeling uncovers global structural features of class I and class II fungal hydrophobins 📜Paper: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pro.7027

2. OmniPert: One Model to Predict Both Gene and Drug Perturbations

Anyone in drug development knows that our daily job is a battle against complexity. We throw a small molecule at a cell or knock out a gene, then hold our breath to see what happens. The process is slow and expensive, and often, all we see is an average effect. It’s like listening to a symphony from outside the concert hall—you can hear the general melody, but you have no idea which violinist hit a wrong note.

Single-cell sequencing technology finally lets us inside the concert hall to hear each musician. But now there’s another problem: listening to one performance at a time (doing one experiment at a time) is still too much work. And we’ve always operated like separate artisans. The gene-editing people and the chemical-screening people have used two different sets of prediction models, each speaking their own language.

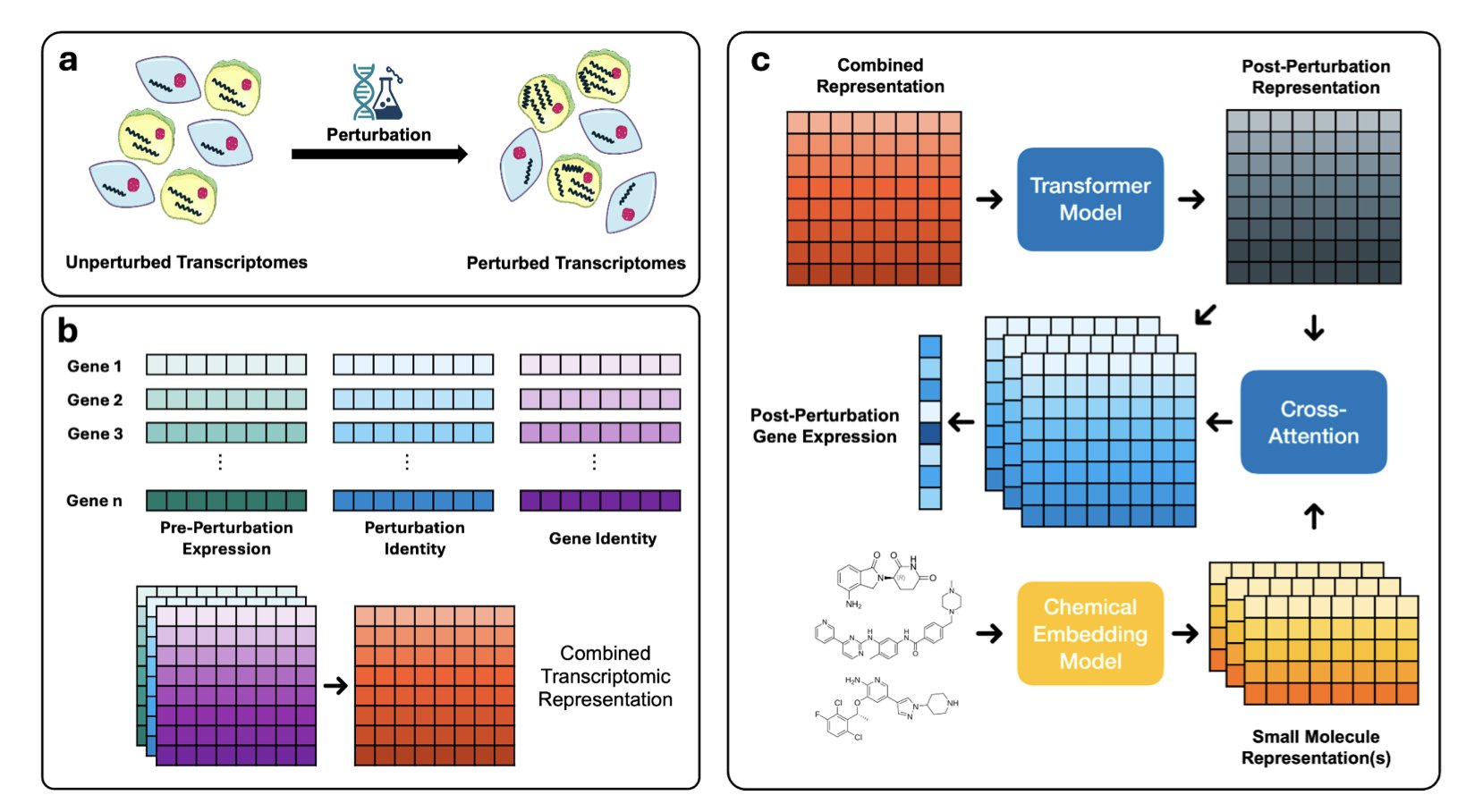

Now, OmniPert is here. The researchers did something quite ambitious: they used a large, Transformer-based model to unify gene perturbations and chemical perturbations. You can think of it as a translator fluent in both biology and chemistry. It was fed a huge amount of single-cell data and learned the patterns of how cells respond to being “messed with” in different ways.

This changes the game. It’s no longer a simple “input A, predict B.” It’s more like a biological “flight simulator.” You can ask it wild questions that used to require expensive wet lab experiments: “If I knock out the star oncogene KRAS in this cancer cell and also treat it with this new compound I have, how will the cell respond? And not just the whole population, but what about a specific sub-population that might be drug-resistant?” In the past, answering this question would have required enough manpower, resources, and time to make any project lead’s head spin. Now, you can run a simulation on your computer first.

Even better is its “counterfactual inference” capability. This is like telling your GPS a destination, and it plans the best route for you. You can tell OmniPert, “I want the transcriptome of this group of cancer cells to look more like normal cells.” It will calculate backward and tell you, “Okay, try knocking down this gene and adding that small molecule.” This turns it from a passive predictor into an active strategist, a potential “military advisor” for drug design. It can inspire us to find therapies that are less toxic and more precise.

Of course, we have to be realistic. Any model’s ability is limited by the quality and breadth of the data it’s “fed.” How well does it generalize to new drugs, new targets, and new cell lines it has never seen before? That is the real test of whether it’s a powerful tool or just a toy. Any tempting hypothesis the model generates must ultimately be validated back at the bench with pipettes and petri dishes.

So, OmniPert won’t put experimentalists out of a job. It will likely make us far more efficient. It’s like a highly capable scout that can help us map out the most promising directions to explore in the vast and dangerous wilderness of drug discovery. In the world of pharma, where resources and time are precious, that alone is immensely valuable.

📜Title: OmniPert: A Deep Learning Foundation Model for Predicting Responses to Genetic and Chemical Perturbations in Single Cancer Cells 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.02.662744v1 💻Code: https://github.com/LincolnSteinLab/OmniPert

3. ADGSyn is Here! Drug Synergy Prediction is Now 3x Faster, More Accurate, and More Efficient

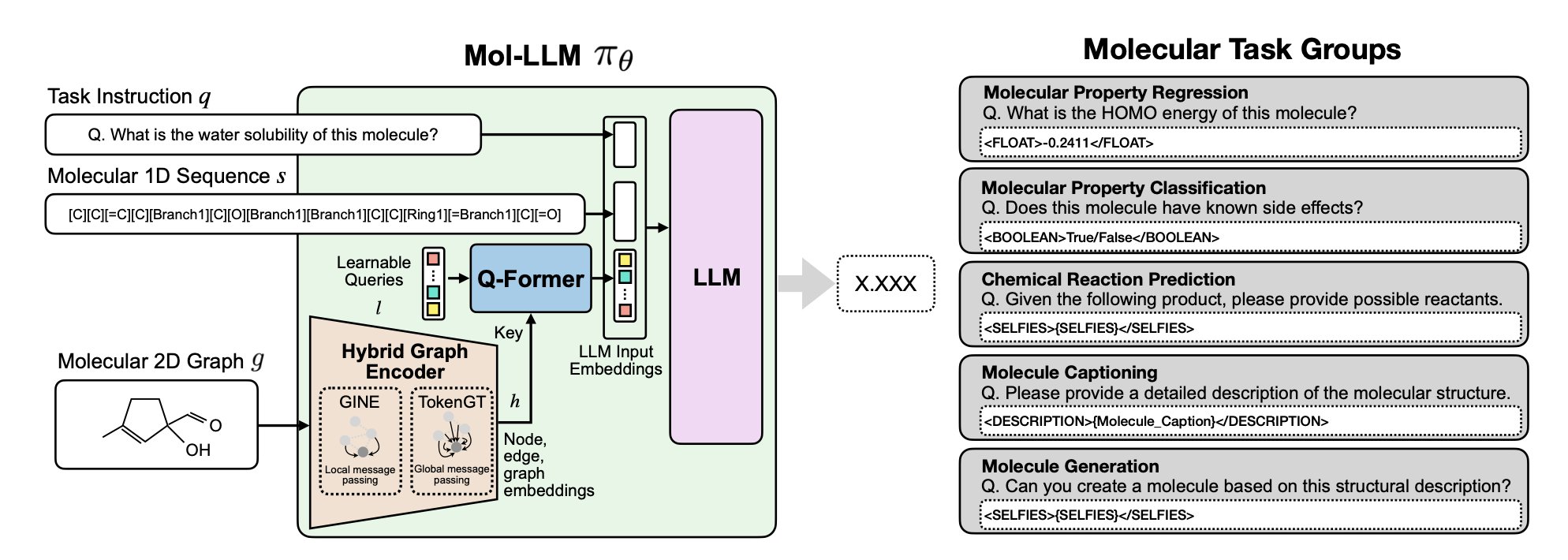

Using anticancer drugs in combination is a key strategy for improving efficacy and overcoming resistance. But quickly and accurately screening for drug pairs with synergistic effects has always been a tough problem. Now, a new model called ADGSyn is here. It uses a dual-stream attention graph neural network (GNN) framework that not only delivers top-tier prediction performance but also drastically cuts down training time.

ADGSyn’s core weapon is its dual-stream attention mechanism. This design explicitly models two key interactions separately: “drug-drug” and “drug-cell line.” This makes its predictions more robust and more biologically intuitive than models that process everything together, like DTSyn and AttenSyn. The researchers also designed shared projection matrices. This acts like a “translator” for different drug molecular features, aligning them in a unified feature space. As a result, the model can better recognize similar chemical structures in different drugs, which greatly improves its ability to generalize and be interpreted—we can see more clearly why the model made a certain judgment.

To make training fast and efficient, ADGSyn also incorporates automatic mixed precision (AMP). The results are impressive: memory usage is cut by 40%, and training speed is boosted by 3x, all without any drop in performance. This means you can run large-scale prediction tasks even on standard consumer-grade GPUs. ADGSyn also takes an unconventional approach to data input. It doesn’t just look at chemical descriptors; it directly processes the entire molecular graph (converted from SMILES strings) and also integrates gene expression profiles from the CCLE database. This way, it considers both structural information and genomic context.

Inside the model, a dual-attention pooling module uses a tanh-activated cross-attention mechanism to dynamically assign weights to interactions between nodes. This is followed by a post-residual LayerNorm to ensure stable gradient propagation and a smoother training process.

To test its performance, the model was benchmarked on the classic O’Neil dataset, which includes 13,243 drug-cell line combinations. ADGSyn outperformed eight baseline models across all major evaluation metrics: AUROC of 0.92, AUPR of 0.91, accuracy (ACC) of 0.86, and a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.72. The Kappa score, in particular, shows that its judgments are highly consistent with those of experts. The researchers also ran ablation studies, removing either the shared projection matrices or the dual-stream attention. The result? Performance dropped significantly. This proves that every component of the model is essential and contributes to its overall power.

Compared to its predecessors like MR-GNN, DTSyn, and DeepSynergy, ADGSyn is just as accurate, if not more so, but with much lower computational cost. Where others take 12 to 15 seconds per epoch, ADGSyn gets it done in less than 4 seconds. The model’s architecture cleverly combines GAT layers (for local and global graph information aggregation), LSTM layers (for modeling sequential structures), and an MLP (for the final synergy prediction), making it well-suited for handling complex and diverse biological data.

Although ADGSyn is already a strong performer in efficiency and accuracy, the research team has bigger goals. They plan to integrate biological network-level information, such as protein-protein interaction or metabolic networks, to further improve the model’s interpretability and expand its applications. ADGSyn sets a new standard for efficient and explainable drug synergy prediction. It is especially useful in research settings with limited resources or in clinical situations that require quick decisions.

💻Code: https://github.com/Echo-Nie/ADGSyn.git 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.19144