Table of Contents

- SLM acts like a detective, using a process of elimination to generate biological sequences. This new diffusion model outperforms much larger models on DNA and protein design tasks.

- The Boltz-ABFE framework successfully uses AI-predicted protein structures for high-accuracy Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) calculations for the first time. This gold-standard technique no longer depends on experimental crystal structures, opening new paths for early drug discovery.

- Researchers developed a new AI workflow that can efficiently predict how proteins and peptides bind, even when their structures are unknown, and it performs well in real-world scenarios.

- The AutoLead framework teams up a creative AI chemist (a Large Language Model) with a rigorous data statistician (Bayesian optimization). Together, they achieve results better than existing methods on the complex task of drug lead optimization.

- Forget complex equivariant networks. Just rotate a molecule a few times and average the predictions. The results are surprisingly good.

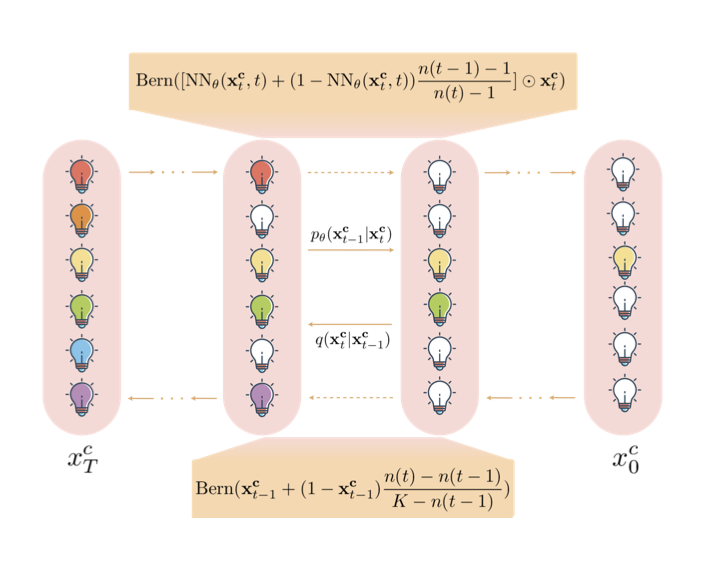

1. The SLM Model: Generating Molecules Like a Detective

We’ve been teaching AI to design biological sequences in a slightly awkward way.

The most common method is using autoregressive models, like GPT. It works like a writer, creating a sentence from left to right, one word at a time. This feels natural for language. But in biology, an amino acid at the end of a protein sequence might be right next to one at the very beginning in 3D space. This “left-to-right” linear thinking isn’t a good fit.

Another approach is diffusion models. They’ve been great at generating images and 3D structures. You can think of it as an AI that restores old photos, starting from a noisy image and gradually bringing back clarity. This is powerful for continuous, smooth data. But biological sequences are made of a discrete alphabet—20 amino acids or 4 nucleotides. It’s like asking a painter who is used to a palette to play with letter blocks. It feels off.

The ShortListing Model (SLM) presents a more intuitive method.

AI Learns to Be a Detective

SLM doesn’t work like a writer or a painter. It’s more like a detective.

When it needs to decide which amino acid to place at a certain position in a protein, a traditional autoregressive model just makes a guess. SLM does something different:

First, it treats all 20 amino acids as “suspects.”

Second, it analyzes clues from the “crime scene”—the chemical environment around that position—and rules out a batch of the most unlikely suspects. For instance, it might decide, “Based on the evidence, this position shouldn’t have a positively charged amino acid, so I’ll eliminate lysine and arginine.”

It narrows down the list of suspects step by step—a process called “shortlisting”—until only the most plausible one remains.

This process is a parallel “elimination” rather than a linear “writing,” which allows it to handle the complex, long-range dependencies in biology more effectively.

Not Just Smart, but Efficient

This detective is both smart and efficient. When eliminating suspects, it doesn’t need to search through a complex, continuous 3D space. It just chooses between a few well-defined “suspect profiles” (called “simplex centroids” in the paper). This simplifies the computation and improves scalability.

The researchers also gave the detective some tools, like a “re-weighted loss function,” which helps when there are too many suspects (like in language models with huge vocabularies) and the detective gets overwhelmed.

How Did It Do?

This new detective made a strong debut.

It achieved state-of-the-art results on DNA promoter and enhancer design tasks.

On protein design tasks, the “lightweight” SLM even outperformed the “heavyweight” ESM2-150M model, which has far more parameters.

This suggests that for AI-driven scientific discovery, the path forward might be finding algorithms that better fit the problem’s nature, rather than endlessly scaling up models and compute power.

📜Title: ShortListing Model: A Streamlined Simplex Diffusion for Discrete Variable Generation

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.17345

💻Code: https://github.com/GenSI-THUAIR/SLM

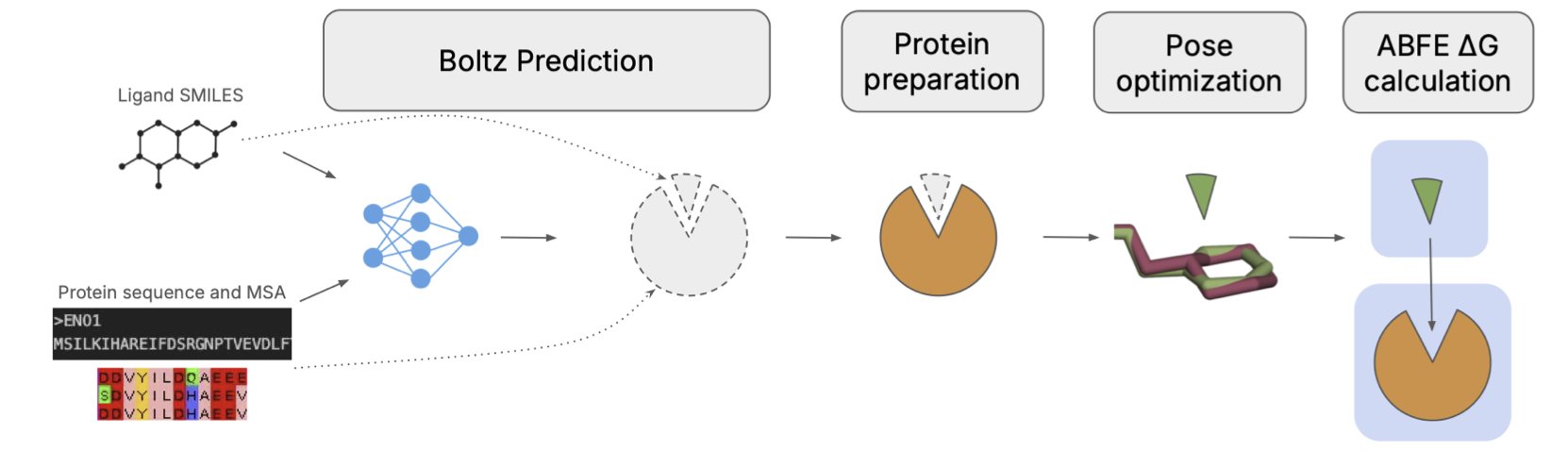

2. AI Finds a Path for FEP, Freeing It from Crystal Structure Dependency

In computational medicinal chemistry, Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) is the gold standard for predicting how strongly a molecule binds to a target protein. But it comes with a condition: you need a high-quality, experimentally solved crystal structure of the protein-ligand complex.

This is a problem in early drug discovery. At this stage, researchers have many newly designed but not-yet-synthesized molecules, so crystal structures are unavailable. As a result, FEP, the tool they need most, can’t be used.

The Boltz-ABFE framework offers a solution.

AI Leads the Way, Physics Provides the Rigor

The idea behind Boltz-ABFE is to use an AI-predicted structure instead of an experimental one.

The research team used an AI model called Boltz-2, which can “co-fold” the protein and ligand simultaneously to directly generate a 3D structure of the complex. This AI-generated structure is then used for the FEP calculation.

AI predictions aren’t perfect.

Guiding and Correcting the AI

The researchers found that Boltz-2 sometimes made errors when predicting the exact chemical structure of the ligand, like getting a chiral center wrong. Such mistakes can have a big impact on the accuracy of FEP calculations.

To address this, the team designed an automated correction workflow. They used the AI-predicted protein pocket and traditional docking software to place a chemically correct ligand back into it. This “proofreading” step improved the quality of the initial structure.

The researchers also noted the importance of optimizing the input. For example, removing low-confidence, flexible regions of the protein sequence before prediction, or including known binding partners in the model. The more biologically relevant the input, the more reliable the output.

How Did It Do?

Across several standard test systems, the binding energies from this “AI prediction + physics calculation” workflow had an average error of less than 1 kcal/mol compared to experimental values. This level of accuracy is good enough to guide the design and ranking of molecules in early drug discovery.

This means FEP is no longer limited to systems with crystal structures. For new targets without structural information, or for projects that need to quickly evaluate many new chemical scaffolds, there is now a first-principles-based computational tool available.

This method won’t replace experiments, but it can help screen out unsuitable molecules beforehand, allowing researchers to focus their resources on the most promising drug candidates.

📜Title: Boltz-ABFE: Free Energy Perturbation without Crystal Structures

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.19385v1

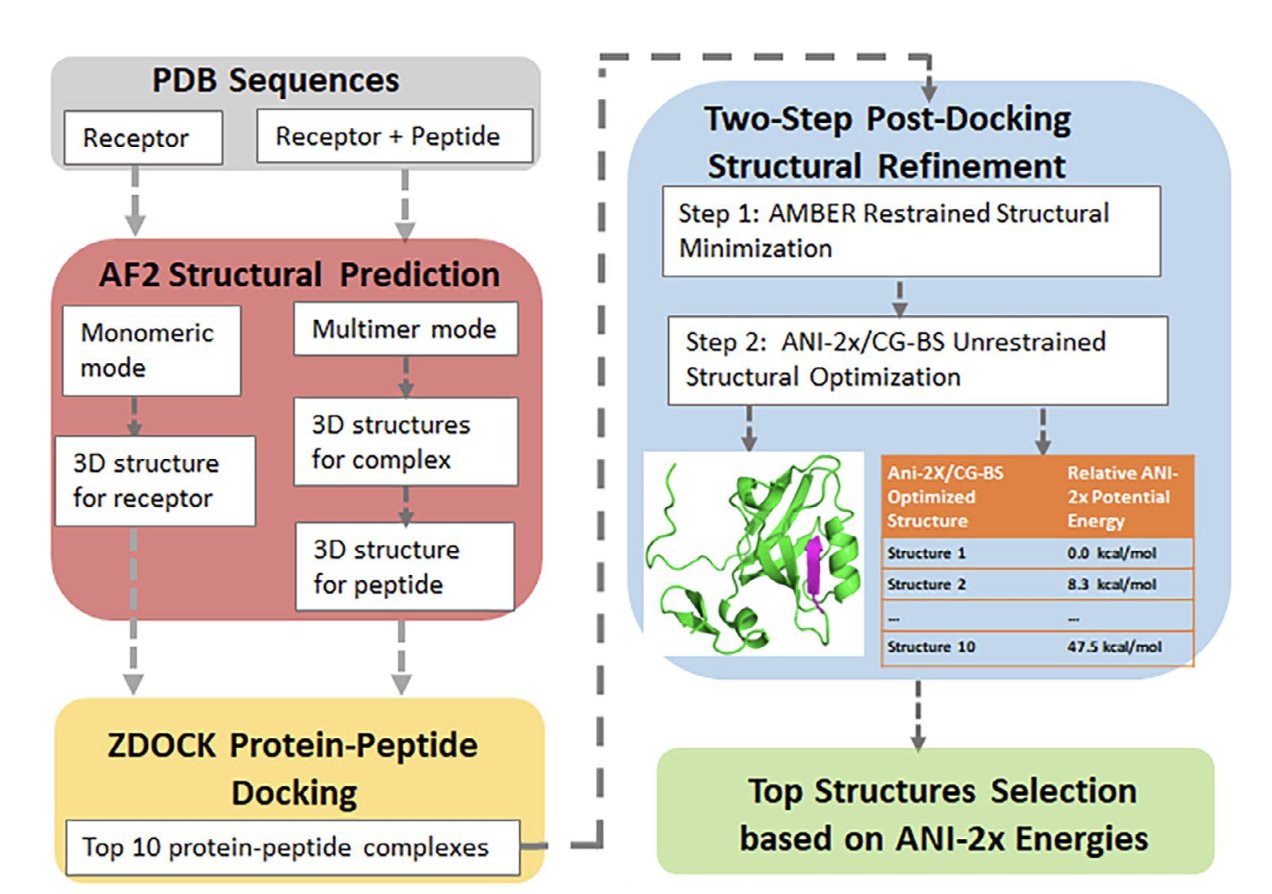

3. AI Protein Docking: Accurate Predictions Without a Structure

The binding of proteins and peptides is fundamental to understanding life and developing new drugs. But when a crystal structure of the complex is missing, predicting how they bind is a major challenge. A research team has developed an AI-assisted workflow specifically to solve this data-gap problem.

At the heart of the workflow are two AI tools: AlphaFold 2 (AF2) and the ANI-2x neural network force field.

The first step is to predict the 3D structure of the receptor protein using AF2 in its monomer mode. Then, AF2 is switched to multimer mode to predict the peptide’s structure, guided by the structural information of the receptor protein. This method of incorporating the receptor’s environment into the peptide prediction helps the peptide adopt a more realistic conformation and is a key innovation of this work.

Once the individual structures are generated, the rigid-body docking program ZDOCK searches for all possible binding poses between the protein and peptide, selecting the top 10 highest-scoring ones. These candidates are first optimized with AMBER, then refined using the team’s CG-BS geometry optimization method and the ANI-2x neural network force field. Finally, ANI-2x re-ranks these poses based on machine-learned energy calculations to identify the best binding mode.

The team tested the workflow on the LEADS-PEP dataset. This dataset includes 62 systems with peptides up to 39 amino acids long, most of which are intrinsically disordered random coils. With no prior structural information for the receptor, peptide, or complex—a strict definition of a “practical scenario”—the workflow achieved a 34% success rate (considering only the top-ranked prediction). This rose to 45% when considering the top three predictions. This is a significant improvement over previous benchmarks that often relied on partially known structures.

The study also found that modeling the receptor and peptide separately with AF2’s monomer and multimer modes, respectively, gave the best results. In a comparison with the docking software Glide, ZDOCK had a higher success rate (27%) than Glide (12.5%) when using AF2-predicted structures as input. The ANI-2x/CG-BS refinement step was also critical. It improved the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the docked structures, boosted the success rate, and was able to correct ZDOCK’s initial results to find the proper binding mode.

The study also explored the model’s ability to predict across different complexes, finding that AlphaFold 2’s modeling can provide a preliminary distinction between binding and non-binding pairs. A current limitation of the ANI-2x force field is that it does not account for solvent and entropy effects. Still, the workflow’s performance is comparable to or better than traditional methods (which report success rates between 4.3% and 24.3%). The code for the ANI-2x/CG-BS optimization has been made open-source, allowing others to reproduce the work and providing a foundation for integrating newer models like AlphaFold 3 or force fields with solvent corrections.

📜Paper: https://onlineliabrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jcc.70137

💻Code: https://github.com/junmwang/pyani_mmff

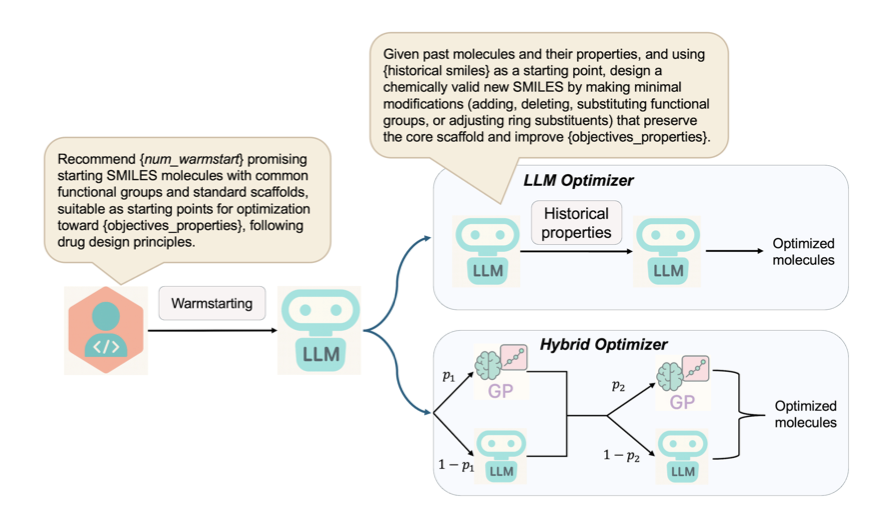

4. AutoLead: LLM and Bayesian Optimization Team Up for Lead Optimization

In drug discovery, turning a hit compound into a clinical lead is an expensive and challenging step. This process requires improving a molecule’s activity while balancing multiple conflicting properties like solubility, toxicity, and metabolic stability. A tiny structural change can affect the molecule’s overall drug-likeness.

Past AI methods have often struggled with this kind of multi-objective optimization, finding it hard to make tradeoffs like a human chemist can.

Assembling an “AI Dream Team”

The idea behind the AutoLead framework is to build an AI team where two models with different specialties work together.

Team Member 1: The Creative Chemist (LLM)

The chemist on the team is a Large Language Model (LLM). It has learned a vast amount of knowledge about chemical reactions and molecular structures. Given a starting molecule, the LLM can propose many chemically intuitive modifications, much like an experienced medicinal chemist. Its strength is divergent thinking, allowing it to explore a broad chemical space.

Team Member 2: The Calm, Rigorous Statistician (Bayesian Optimization)

The statistician on the team is Bayesian Optimization, implemented with a Gaussian process model. It evaluates the many proposals from the LLM based on existing experimental data and uncertainty. Its job is to manage risk and optimize for efficiency by building a predictive model to identify the most promising modifications and guide exploration into unknown chemical space.

Dynamic Collaboration

The key to AutoLead is the dynamic collaboration between the two models. The workflow is iterative: the LLM first proposes a batch of candidate molecules, then the Bayesian optimization model evaluates and ranks them, selecting the most promising ones for the next round. This approach combines the creativity of the LLM with the rigor of Bayesian optimization.

To test the framework’s performance, the researchers designed a new benchmark called LipinskiFix1000. The task is to fix a batch of molecules that violate the classic “Rule of Five,” making them drug-like again while also improving other properties like the Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED).

AutoLead outperformed other current methods on this new benchmark and on several existing ones. The results show that for solving complex multi-objective optimization problems, this strategy of combining the strengths of different AI models is more effective than using a single method.

AutoLead’s success suggests that the future of AI in drug discovery may lie in building AI workflows that mimic the collaborative work of expert teams, rather than searching for a single, all-powerful model.

📜Title: AutoLead: An LLM-Guided Bayesian Optimization Framework for Multi-Objective Lead Optimization

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.19.671029v1

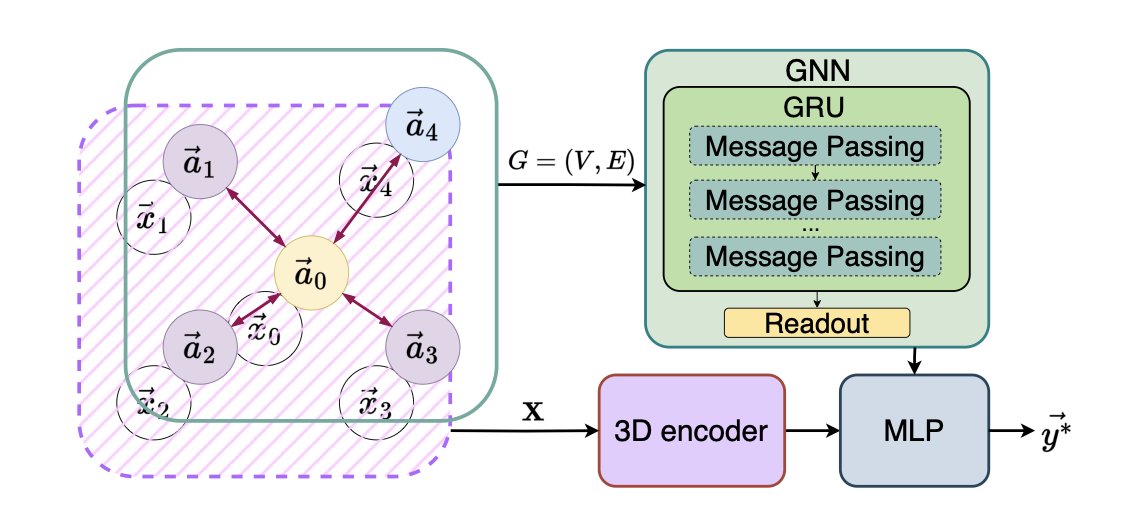

5. Rotate the Molecule, Get Better Results? A New Idea for 3D GNNs

Researchers in 3D molecular modeling are all familiar with the problem of rotational invariance. A molecule is the same no matter how you rotate it, but for a model, a change in atomic coordinates can lead to very different predictions. It’s like how we can recognize an upright face but might not immediately recognize it upside down.

In the past, there were two main schools of thought for solving this. One was the “manual” approach, relying on chemical intuition to hand-craft a set of rotation-invariant features like bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles. This method is reliable, but it’s like trying to describe a sculpture using only a ruler and a protractor—you lose a lot of 3D spatial information. The other was the “academic” approach, which used complex mathematical tools to develop various SE(3) equivariant neural networks. These networks are theoretically perfect but are complicated to implement, slow to train, and their sophisticated design can sometimes hurt their ability to generalize.

The authors of a new paper propose a pragmatic solution. Their idea is: since perfect equivariance is hard to achieve, let’s try something else. Just rotate the molecule randomly in space dozens of times, have the model make a prediction for each rotation, and then average all the predictions.

The core idea is simple and direct: approximate rotational invariance by sampling multiple random rotations of the input molecule and averaging the predictions, thereby avoiding complex equivariant architectures. A single prediction might be off due to a poor molecular pose, but when you average predictions from different angles, the final result tends toward a stable and accurate central value. It’s like an experienced jury reaching a fair verdict by viewing the evidence from multiple perspectives.

The biggest appeal of this method is that it’s “plug-and-play.” It’s a standalone encoder that can be seamlessly integrated into existing Graph Neural Network (GNN) models, improving their robustness without needing to modify the main code.

Tests on standard datasets like QM9 confirmed its effectiveness. On small datasets with only 3,000 or 10,000 samples, this method performed better than traditional radial basis function (RBF) features and the PointNet architecture. This suggests that when data is scarce and models are prone to overfitting, this simple “take a few more looks” approach is more robust. It forces the model to learn more fundamental structure-activity relationships that don’t depend on a specific orientation.

Interestingly, this method doesn’t conflict with other tools. It can be combined with carefully designed geometric features, and the two can complement each other to improve performance. This shows that data-driven representation learning and prior knowledge-based feature engineering can work well together.

As for computational cost, even though it requires dozens of predictions, the rotation and prediction operations can be done in parallel. On a GPU, the additional overhead is small. It’s a worthwhile trade-off to gain a significant boost in model robustness for a small amount of extra compute.

So, when your 3D model’s performance is fluctuating because of molecular pose issues, you might want to try this simple, direct approach first—let your molecules spin.

📜Title: Rotational Sampling: A Plug-and-Play Encoder for Rotation-Invariant 3D Molecular GNNs

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.01073