Table of Contents

- An autonomous AI agent designs a dual-target antibiotic from scratch, demonstrating a fully automated process to fight superbugs.

- We finally have a mathematical tool that speaks chemistry’s native language, allowing AI to see molecules not as a collection of atoms, but as a network of connections.

- IDFlow uses physical energy as a “navigator” for AI, guiding it away from blind imitation toward a targeted search for the most stable and realistic 3D structures.

1. An AI Agent’s “Two-Pronged Attack” on Superbugs

For decades, we’ve been losing the battle to develop new antibiotics. Whenever a new drug appears, Gram-negative bacteria like Klebsiella pneumoniae quickly figure out how to defeat it. It’s like a never-ending game of whack-a-mole, and our toolbox is running low.

One widely accepted strategy is to stop attacking just one target. If you can destroy the enemy’s munitions factory and their escape route at the same time, your odds of winning get a lot better.

The AI’s Pincer Movement

Researchers chose two targets: the FabI enzyme and the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump. The FabI enzyme is a key machine on the “production line” bacteria use to build their cell membranes. The AcrAB-TolC efflux pump is the “escape hatch” bacteria use to expel drug molecules.

Attacking both at once creates a pincer movement.

Once the strategy was set, the job of executing it was handed to an AI.

The Autonomous AI Project Manager: Moremi Bio Agent

The star of this work is an AI agent called Moremi Bio. It isn’t just a simple generative model; it’s a fully automated project manager.

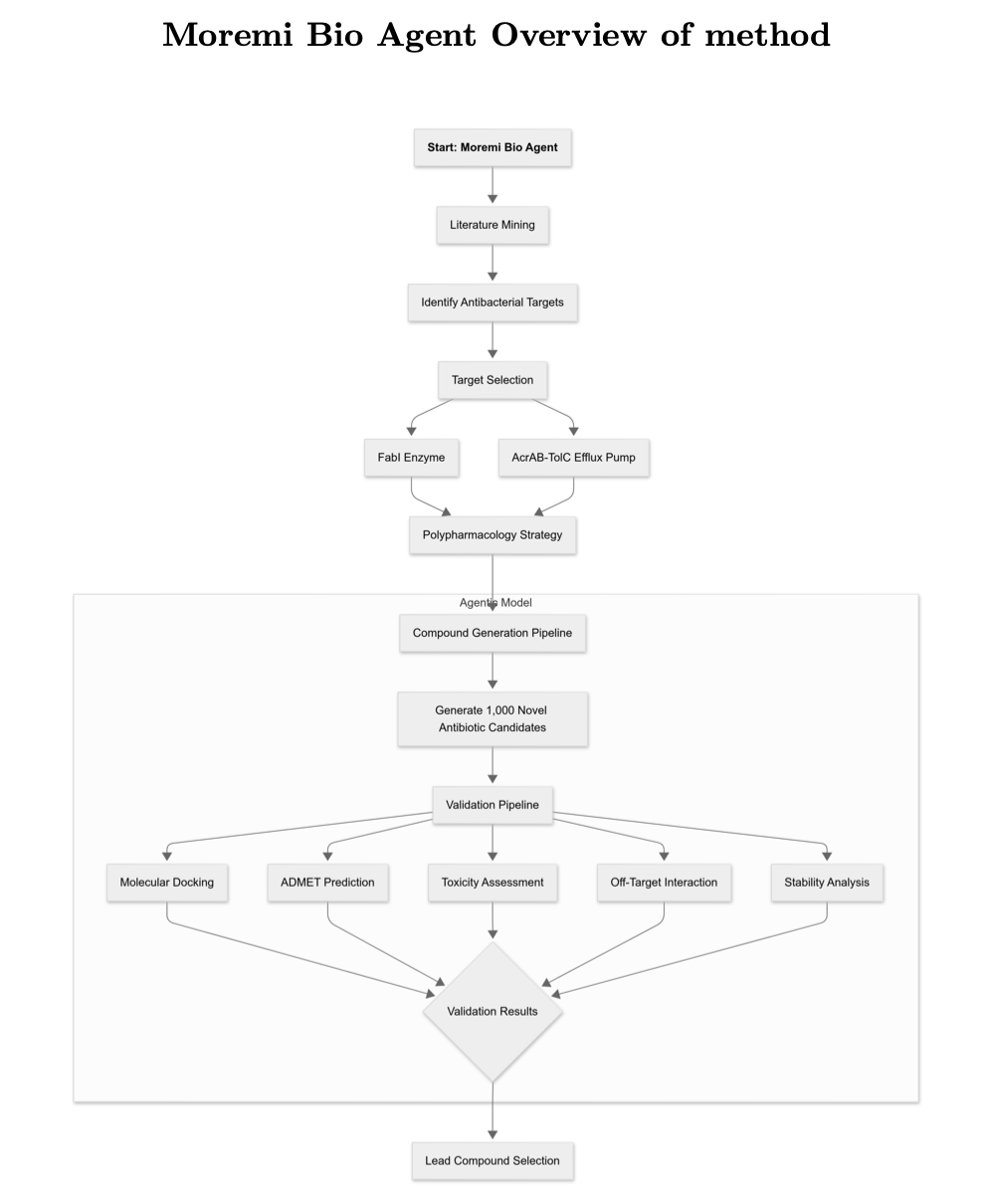

Here’s how its workflow runs:

First, Generation. It designs 1,002 new molecules that could, in theory, inhibit both targets.

Second, Screening. It runs each of the 1,002 molecules through molecular docking, ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion), and toxicity predictions.

Third, Ranking. It scores and ranks the molecules that pass the initial screening based on their drug-likeness.

The entire process is completely autonomous.

The AI’s Results

Of the 1,002 initial molecules, 774 passed the preliminary ADMET benchmarks. In the end, the AI project manager delivered a short list of 60 candidate molecules.

Analysis showed that 391 of the molecules displayed “moderate” binding affinity for both targets.

But we need to be realistic about the word “moderate.”

The AI can’t yet design a nanomolar-level drug ready for clinical trials in one shot. These 60 molecules are more like a batch of high-quality lead compounds—a valuable starting point for development.

And that is the value of this work.

In traditional drug discovery, finding a starting point with dual-target activity and good drug-like properties could take a team a year or more.

Moremi Bio completed this difficult from-scratch exploration efficiently inside a computer.

This work demonstrates an engineering solution that can solve a real-world problem. It provides a better starting point, allowing researchers to focus their energy and resources on optimizing these promising molecules into actual drugs.

📜Title: Moremi Bio Agent: Leveraging Agentic Large Language Model for the Discovery of Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics for Enterobacteriaceae 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.21.671656v1

2. Graph Neural Networks: The Universal Language of Chemistry

For decades, we’ve tried to teach computers chemistry. The process was like describing a Ferrari to a blind person over the phone. You can list all the specs—four wheels, two doors, a V12 engine, a red body—but they will never grasp the essence of the machine: how all the parts connect in a beautiful and efficient way.

Past machine learning methods worked just like that. For each molecule, we would calculate hundreds of “molecular descriptors” like molecular weight, logP, number of rings, and hydrogen bond donors and acceptors. This is basically a detailed parts list. We fed this list to an AI and hoped it would figure out chemical principles. The AI sometimes guessed correctly, but it never really understood.

This review paper announces that a new era may have arrived. We’ve found a better language for communicating chemistry to AI.

Welcome to the World of Graphs

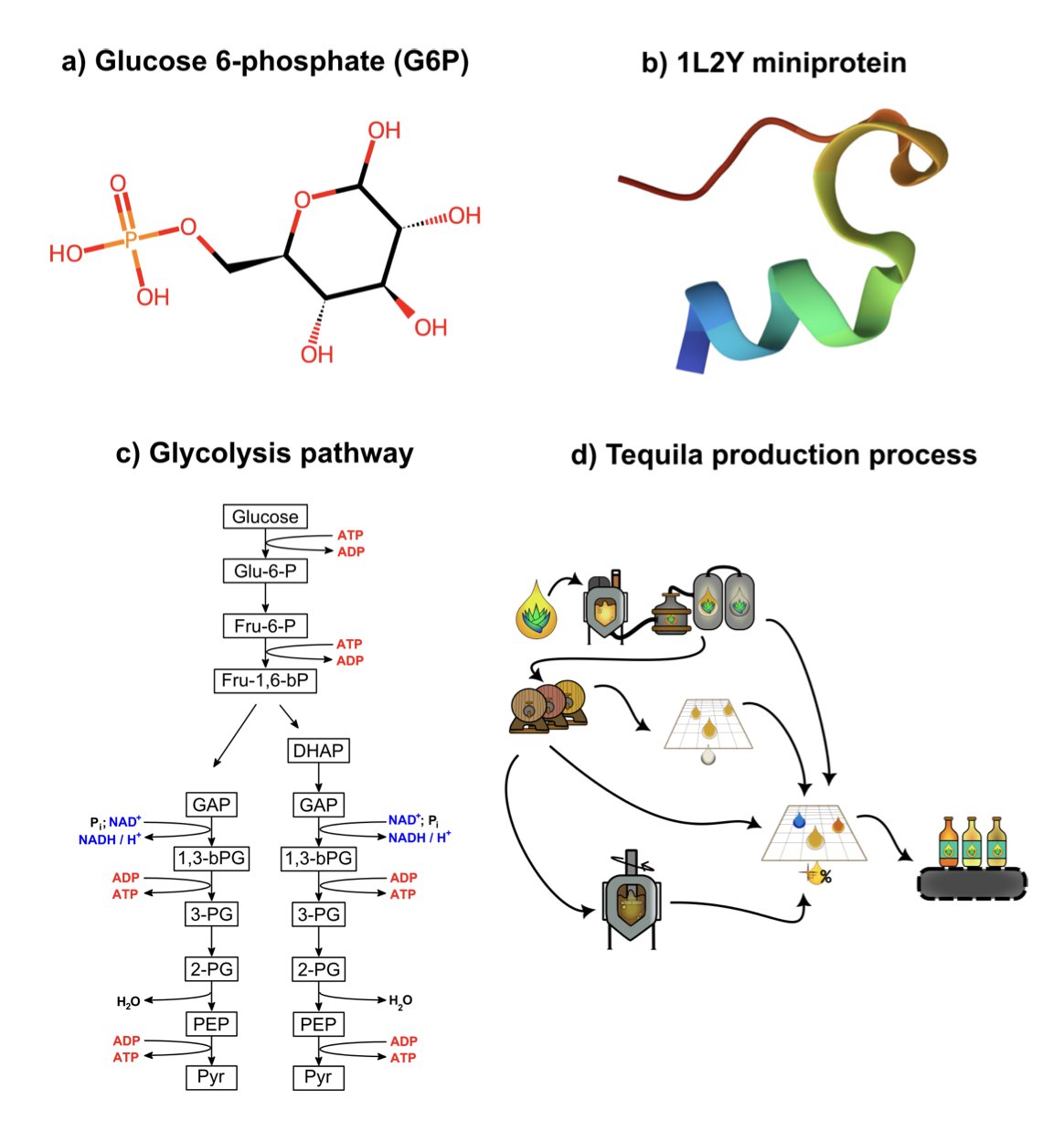

This new language is the graph. In mathematics, a graph is defined simply: a collection of nodes and the edges that connect them.

Now, think about a chemical molecule. It’s a collection of atoms (nodes) and the chemical bonds that connect them (edges).

The correspondence is perfect.

When we represent a molecule as a graph, we’re not just telling the AI, “There’s a carbon atom here and an oxygen atom there.” More importantly, we’re telling it: “This carbon atom and that oxygen atom are connected.”

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are AIs built to interpret this graph language.

The way they work is chemically intuitive. Information passes between connected atoms. A carbon atom will pass information to its neighbors, like “I’m an sp2-hybridized carbon bonded to an oxygen and a nitrogen.” The neighbors receive this information and pass it on to their own neighbors. After a few rounds of this message passing, every atom in the molecule has a rich, deep understanding of its local chemical environment.

This is why GNNs perform so well at predicting molecular properties. They are no longer guessing based on a scattered parts list. They are making judgments after understanding the entire “design blueprint” of the molecule.

More Than Just Molecules

The beauty of this method is its universality.

A glucose molecule is a graph. The entire glycolysis pathway is also a graph, but now the nodes are metabolites and the edges are the chemical reactions that catalyze the transformations. We can use the exact same mathematical framework to study problems at completely different scales.

This review also looks to the future: 3D graphs that can understand spatial information, time-dependent graphs that describe chemical reaction processes, and vast knowledge graphs that connect drugs, targets, and diseases.

Graph Neural Networks are not just another buzzword. They represent a shift. We’ve finally stopped trying to force-translate chemistry into long strings of numbers that computers can process. Instead, we’re starting to teach computers the native language of chemists—structure and connection.

📜Title: Graph Data Modeling: Molecules, Proteins, & Chemical Processes 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.19356