Table of Contents

- UTGDiff is an AI that can read a chemist’s text instructions and translate them into new molecular structures, making on-demand molecular design possible.

- AlphaFold3 has evolved, now including non-protein molecules in its predictions for the first time. But official CASP16 results show it isn’t invincible, especially with complexes, RNA, and hard targets. Older methods paired with clever strategies can still compete.

- ESMDynamic has learned from vast numbers of protein “movies” and can quickly predict a protein’s dynamic behavior from a single amino acid sequence—a task that used to require a supercomputer.

1. AI Designing Molecules from Instructions: From Text to Graph

Getting a computer to design molecules often involves a communication barrier. A chemist might want to give an instruction like: “Design a molecule with a pyridine ring connected to a thiazole ring by an amide bond, and it needs to have good solubility.” But AI couldn’t understand that directly. Past tools required machine languages like SMILES or complex parameters to constrain the generation process. It was like asking an architect to build a house based on the number of bricks, not a blueprint.

Older AI models could only match keywords, not grasp the underlying design intent. It’s like telling it “I want something blue with four wheels,” and it gives you a blue shopping cart.

A new study from Peking University and The University of Hong Kong has taught this keyword-matching AI how to read the blueprint.

How did the AI learn to connect words and pictures?

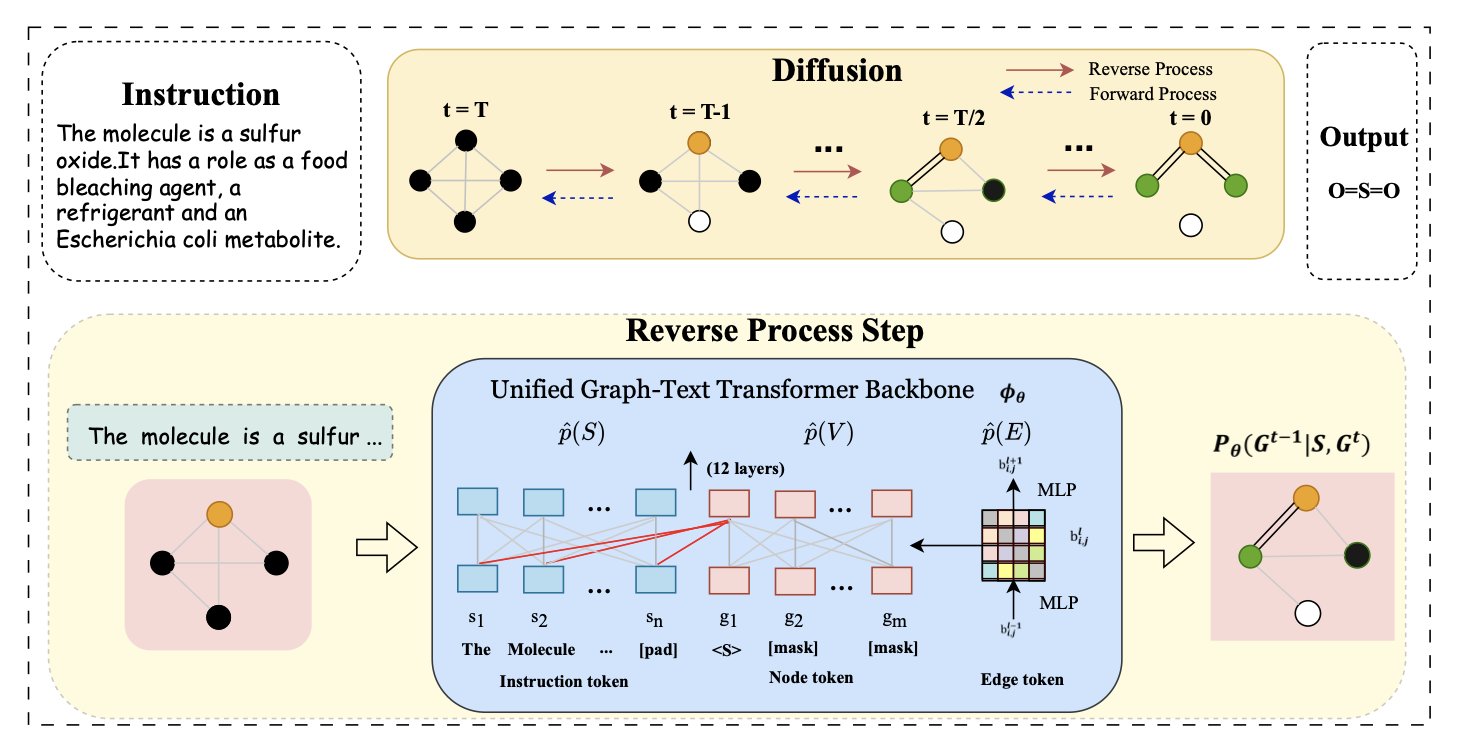

The new model is called UTGDiff. It doesn’t treat text understanding and molecular graph generation as two separate tasks forced together. Instead, it places both within a unified framework, allowing them to “talk” to each other throughout the generation process.

UTGDiff uses a method called a Diffusion Model. The process is like restoring a noisy old photograph. It starts with a blurry molecular graph made of random atoms and bonds, along with a clear text instruction, such as “I want a thiazole with a pyridine ring.”

The AI’s job is to gradually remove the noise from this graph. The key is that at each step of this denoising process, the AI refers back to the text instruction to check if its action is bringing the molecule closer to the described structure.

This continuous, fine-grained text guidance during generation is UTGDiff’s core mechanism. It uses the text instruction to course-correct at every step, ensuring the process stays on track.

How were the results?

Once the AI learned to build molecules by following instructions, the quality of the generated results improved significantly.

UTGDiff outperformed existing methods on several tasks. The molecules it generated had a higher similarity to the human instructions and better chemical validity—it wasn’t just producing random, useless combinations.

UTGDiff also showed excellent zero-shot capabilities. It could understand and execute new instructions it had never seen during training, without needing extra training.

This work changes how we generate molecules. We can start to tell a machine the ideas in our heads and watch them turn into real molecular structures.

📜Title: Instruction-Based Molecular Graph Generation with Unified Text-Graph Diffusion Model 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.09896 💻Code: https://github.com/ran12/UTGDiff

2. AlphaFold3 at CASP16: Evolved, but Not Yet a God

Since its release, AlphaFold3 (AF3) has drawn both praise and skepticism. Now, the results from the authoritative CASP16 structure prediction competition are out, giving us a chance to see how AF3 really performs on a level playing field.

The biggest change: from specialist to general practitioner

AF3’s biggest advance over AlphaFold2 (AF2) is that it’s no longer limited to proteins. It has learned to handle small molecules, nucleic acids (RNA), and ions. For drug discovery, this simplifies the workflow. Before, you might use AF2 to predict a target’s structure, then use different software to predict how a drug molecule would bind to it. AF3 combines these two steps into one.

Think of it this way: AF2 was like a master carpenter for proteins—highly skilled, but only did woodwork. AF3 is more like a general contractor who can handle plumbing and electrical work in addition to the carpentry. This simplifies the whole process and makes it more accessible to non-computational experts.

Head-to-head: Is it really that much better than AF2?

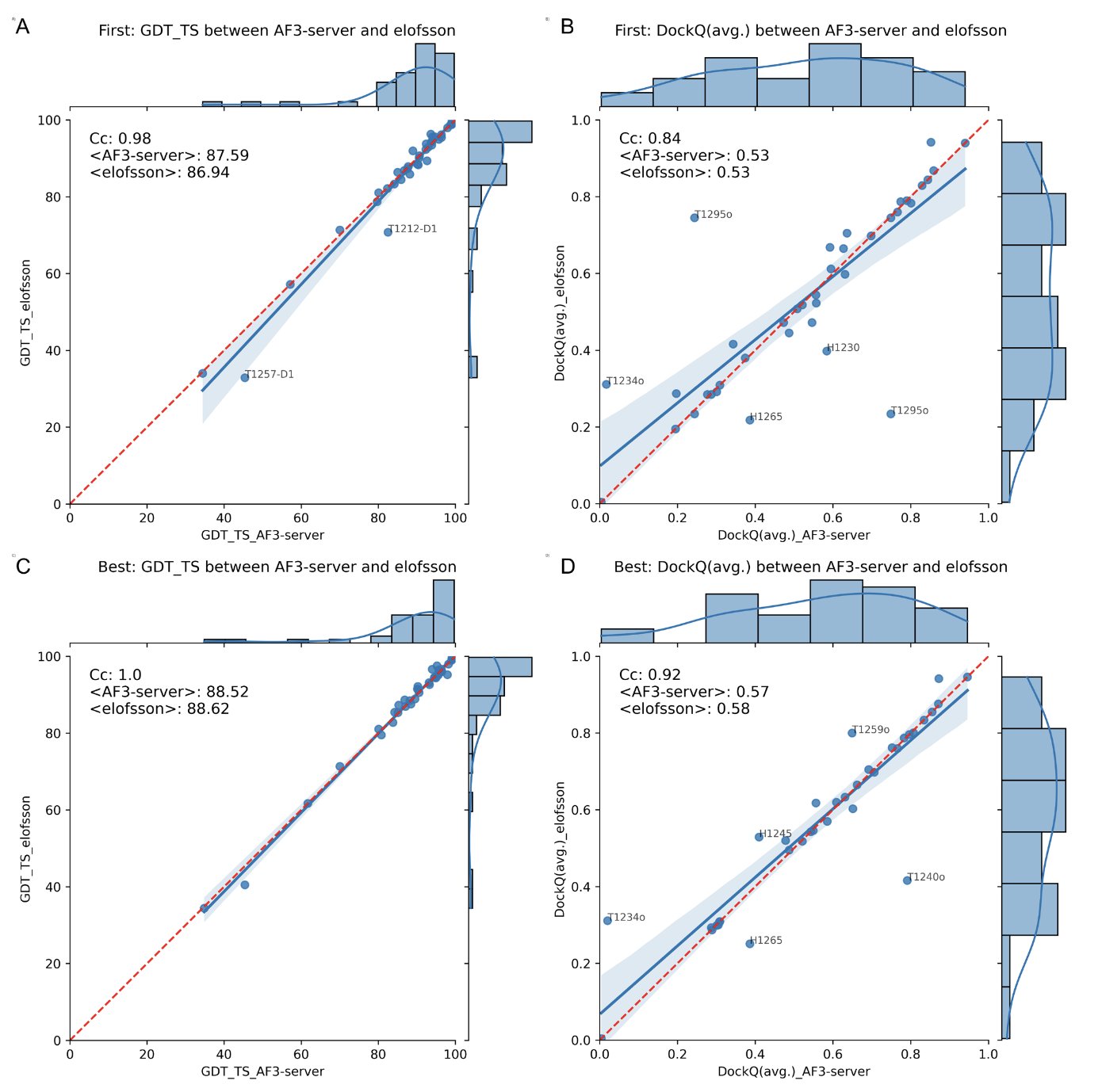

AF3 is better than AF2, but the advantage is limited.

When predicting protein complexes, AF3 performed slightly better than AF2. But an interesting finding was that if you give AF2 enough computing power for “massive sampling” (basically, brute-force trial and error), its final performance is no different from AF3’s.

This suggests that AF3 might not have made a fundamental breakthrough in its core protein structure prediction engine. Its advantage lies more in integration and ease of use than in a leap in raw predictive accuracy.

Where the cracks appear: What are AF3’s weaknesses?

Every tool has its limits, and AF3 is no exception. The CASP16 results highlighted several of its weak spots.

First is the stoichiometry of complexes. When predicting multi-subunit protein complexes, AF3 often gets the number of each subunit wrong. It can draw a beautiful engine but might leave out a few pistons. For understanding how biological machines work, this is a fundamental flaw.

Second is RNA structure. RNA is like a cooked noodle—flexible and without a fixed shape—and predicting its structure has always been a challenge. AF3 gave it a try, and the results were decent, but it’s nowhere near as dominant as it is with proteins. It didn’t even win the top spot in this category.

Finally, there are the high-difficulty targets. For novel structures with few homologous proteins to reference—the “hard problems”—AF3’s performance did not surpass other top methods. When exploring the unknown territories of biology, we still need to rely on a variety of tools and human ingenuity, not a single “magic bullet.”

A new challenge: How to pick the best from a pile of “correct” answers?

Like AF2, AF3 doesn’t just give you one answer. It outputs a set of plausible models. This creates a new problem: how do you choose the one that’s closest to the real structure? The CASP16 report also emphasized that while our ability to predict structures is improving rapidly, our ability to evaluate and select the best model is lagging behind.

AF3 is a remarkable engineering achievement. It’s more versatile and easier to use, further lowering the barrier to structure prediction. But it’s not magic, and it’s not the end of structural biology. The hard problems are still there. As old problems are solved, new ones emerge.

📜Title: AlphaFold3 at CASP16 📜Paper: https://onlineliibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/prot.70044

3. ESMDynamic: Predicting Protein Dynamics from a Single Sequence

AlphaFold is like a high-precision camera that takes sharp, static “passport photos” of proteins. But inside a cell, proteins are dynamic; they’re like complex machines constantly twisting and folding. Drug molecules often bind to transient “active” conformations that can’t be seen in these static photos.

To observe protein dynamics, we need molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. MD is like a video camera for the molecular world, but it’s slow and requires a huge amount of energy. Getting a meaningful dynamic “movie” can often take a computing cluster weeks to run.

ESMDynamic offers a fast-forward button.

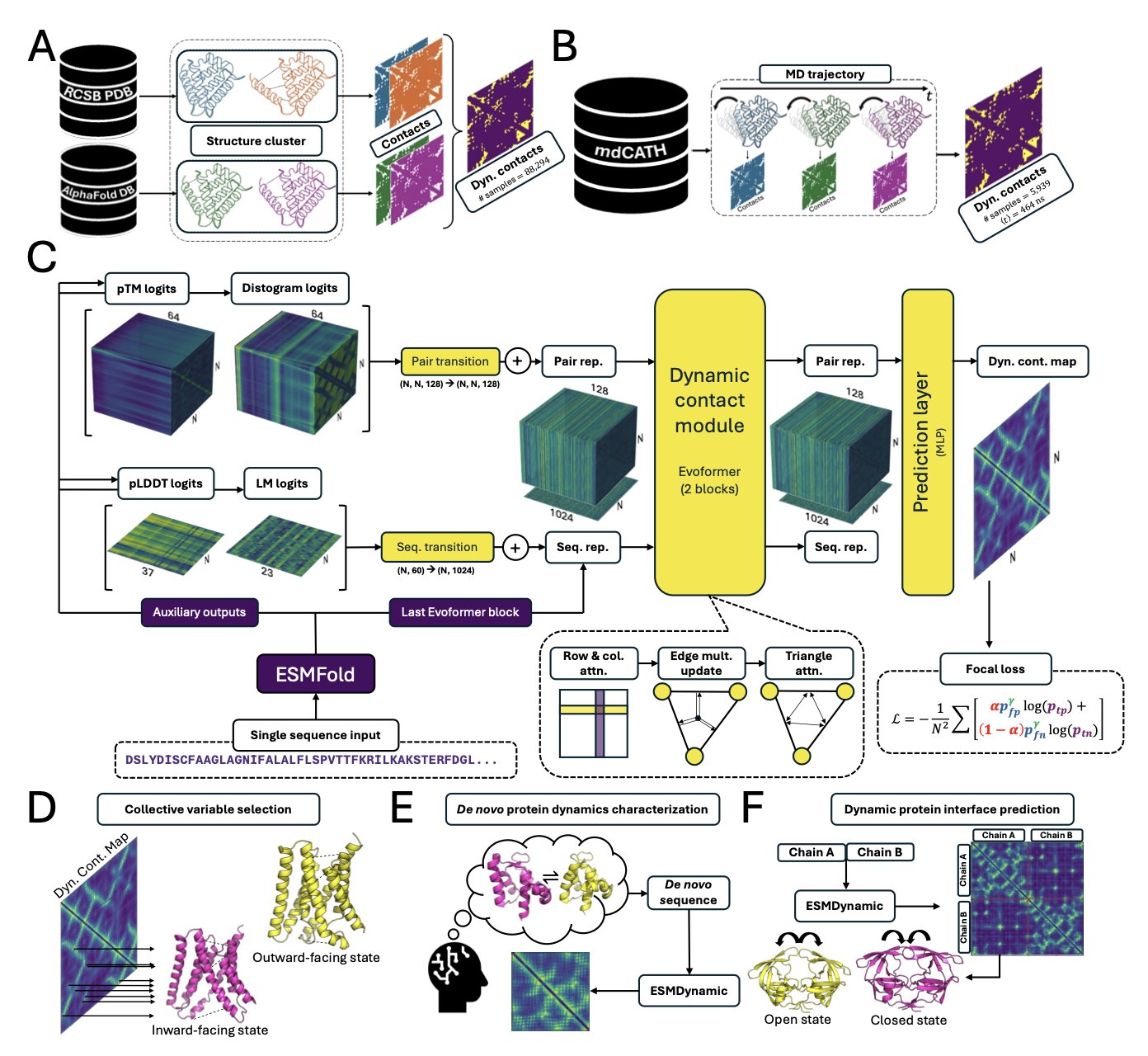

How the AI learns

ESMDynamic works by learning from massive amounts of existing protein dynamics data—some from experiments, some from large-scale MD simulations. By doing this, it has learned the patterns connecting protein sequences to their dynamic behaviors, much like a film director who has watched countless movies and mastered the art of storytelling. It can recognize which amino acid sequences will form flexible loops or cause a protein’s pocket to open and close.

When you input a new amino acid sequence (the “script”), ESMDynamic can use the patterns it has learned to quickly predict which amino acids (the “actors”) will have frequent dynamic contacts with each other.

Putting it to the test

On two large-scale MD datasets, ESMDynamic’s performance was comparable to more complex models that require more input (like AlphaFlow), but it was much faster.

It also performed well on several key challenges:

ESMDynamic provides an efficient “scouting tool.” Before committing huge computational resources to a full simulation, you can use it to quickly identify the key regions of protein dynamics worth focusing on, predicting where the “plot twists” are likely to happen.

📜Title: ESMDynamic: Fast and Accurate Prediction of Protein Dynamic Contact Maps from Single Sequences 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.20.671365v1